|

US Landing Craft Tank (Rocket)

- D Day

British LCT (R)s Crewed by the US Navy

1 - Lt Commander Carr's

Recollections. 2 - Diary entries of Seaman Ist Class, Jack Nicholas.

Background

These

personal recollections of Lt Commander Carr, Group Commander

of a flotilla of US Landing Craft Tank

(Rocket), US LCT (R)s, during operations off Normandy and Southern France in the summer of 1944. His

story starts with a brief aside concerning Pearl Harbour in 1941.

[Photo;

LCT (R) 440 was a sister ship of those mentioned in this account.

She is at anchor in the Solent, 3 June, 1944, On D-Day she supported the assault

of 69th Brigade, 50th Infantry Division, on King beach, Gold area. © IWM (B

5263)].

On December 7th, 1941, I was a Storekeeper 3rd Class on

the USS Antares, a stores issue ship returning from a mission south to Canton

Island. We passed through the submarine nets at the entrance to Pearl Harbour at

approximately 0625 and saw the conning tower of what we believed was a

Japanese midget submarine. Since the Antares was unarmed we alerted the

destroyer USS Ward, which was close by. The Ward depth charged the

submarine and struck the first blow in the war with Japan.

This action took place one and a half hours

before the Japanese planes attacked at

0755 that morning. We proceeded into the harbour but soon reversed to clear the harbour entrance

on realising the Japanese intention to sink us in the harbour mouth to

entrap the ships anchored inside.

In August 1942, we arrived in New Caledonia,

where I was ordered to report to Columbia University in New York City for

midshipman training. I completed the course in March 1943, commissioned an ensign and ordered to the Amphibious Base in Little Creek,

Virginia for Landing Craft Tank (LCT) training.

Organisation and Training

In September 1943, a ‘Special Support Group’

was established at the Little Creek

amphibious base near Norfolk, Virginia with a nucleus of three officers, Lieutenant Commander Louis E Hart, Lieutenant

D P G Cameron and myself, Lieutenant (jg) Larry W Carr, (jg = Junior Grade). We

were to train crews for what became ‘Gunfire Support Craft’ during

the initial assault phase of major amphibious beach landings. I

became Group Commander of the 14 LCT (R)s that became part of that group with Lt

D P G Cameron as my executive officer. In addition to these craft, we

also provided for 9 Landing Craft (Flak) and 5 Landing

Craft Gun (Large). All these craft would provide additional

in-shore support and cover for the troop carrying landing craft. Our LCT

(R)s were all British Mk3 LCT conversions,

which were twice

the size of the equivalent US Navy vessels.

As our Command

developed and expanded, in October 1943 we moved to Camp Bradford, Virginia.

We were soon responsible for144 officers and

1537 men recruited from all branches of the US Navy, including small boat crews,

midshipman schools, armed guard and boot camps. Training was provided in gunnery, fire-fighting,

recognition, gas warfare and communications. In addition, many officers and men practiced ship handling onboard LCTs. We were gaining

knowledge and skills but we

still required to organise crews

and appoint commanding officers; it was a slow process.

During late October 1943, we

were on the move again, this time to Fargo Building, Boston,

Massachusetts. As our duties and responsibilities intensified,

both officers and men attended Price’s Neck, an

anti-aircraft training centre on Rhode Island, for training

on

20mm and 40mm guns. Recognition of German aircraft followed, while

we waited to receive sailing orders for overseas

duties. When these came, the men were organised into groups

of twenty five and frequent musters were held to perfect the

training we had received. Essential equipment

arrived, including rifles, packs and foul weather gear and by November 20th,

1943, preparations were completed. We sailed for New York and on November 22nd,

departed the city aboard the Queen

Elizabeth bound for Scotland.

We arrived at Roseneath on the 28th,

known to us as US Navy European ‘Base

II’. Our converted British LCTs would not arrive for several

weeks, so a temporary operations base was set up

to include maintenance and engineering units

with associated training programmes in the technical

aspects of the unfamiliar British equipment

we were about to receive. These included

gunnery, communications and engineering, particularly the Paxman-Ricardo diesel engine.

Crews were also given further training in seamanship and the use of small arms.

Group

Formation

The LCT (R) group was organised on December 15th, 1943, as part of the

‘Special Support Group’, with myself, Lt. (jg) L W Carr appointed as group

commander. Officers in charge of particular craft were

assigned and their crews appointed. They were to become Division 1 of the

LCT (R) Support Craft of Force "O" (Omaha) of the US Eleventh Amphibious Force.

The staff consisted of: Ensign (Assistant Group Commander) D

G Swallow; Ensign (Gunnery Officer) F

D Michael; Ensign (Radar Officer) R

W Bennison; Ensign (Engineering officer) W

E Howard and Ensign (Communications Officer) E.

Bernstein.

The original complement of an LCTR was

seventeen men and two officers, with

fourteen craft assigned to the group. Commanding officers and assistant officers

were appointed as follows;

LCTR 366 Lieutenant

(jg) J C Ogren

& Ensign C M Podrygalski; LCTR 368 Lieutenant

(jg) G A Karlsen

& Ensign F A

Smith; LCTR 423 Lieutenant

(jg) W S Caldwell

& Ensign T J

Hurley; LCTR 425; Ensign R

W Ellicker & Ensign E

J Michalik; LCTR 439 Lieutenant

(jg) E H Mahlin

& Ensign G F

Fortune; LCTR 447 Lieutenant

(jg) W L Kessler

& Ensign A G

Rud; LCTR 448 Ensign B

Y Hess & Ensign B

P McDonald; _small2.jpg) LCTR 464

Ensign H

H Boltin & Ensign A

J Onofrio; LCTR 450 Ensign P

R Smith & Ensign T

A Cassidy; LCTR 452 Lieutenant

(jg) W B McCorn & Ensign R

L Payne; LCTR 473 Ensign G

M Taylor & Ensign P

H Prible; LCTR 481 Ensign A P

Dowling & Ensign A

G Hunter; LCTR 482 Lieutenant

(jg) H M Leete

& Ensign C A

Pink and LCTR 483 Ensign R

H Tucker & Ensign

E J Mack. LCTR 464

Ensign H

H Boltin & Ensign A

J Onofrio; LCTR 450 Ensign P

R Smith & Ensign T

A Cassidy; LCTR 452 Lieutenant

(jg) W B McCorn & Ensign R

L Payne; LCTR 473 Ensign G

M Taylor & Ensign P

H Prible; LCTR 481 Ensign A P

Dowling & Ensign A

G Hunter; LCTR 482 Lieutenant

(jg) H M Leete

& Ensign C A

Pink and LCTR 483 Ensign R

H Tucker & Ensign

E J Mack.

[Photo courtesy of Becky Kornegay, whose father, Quaver Stone

Stroud, served on US LCT (R) 439. The photo shows 439

proceeding in convoy for Normandy (6th June 44) or the South of France (15th

August 44) with her rows of rocket launchers clearly visible].

In Portsmouth on December 20th, 1943, Mk3 LCT

(R) 368

was the

first craft assigned to our group. It was in poor condition having seen

extensive service in the Mediterranean theatre as an LST

before conversion to an LCTR. LCT (R) 366 followed a short time later under similar circumstances

and by January, after

much cleaning and repairing, the 366 and 368

commenced training with the

British as part of the US Navy LCT (R) Group. Both attended an Assault Gunnery School

at HMS Turtle near Poole

in Dorset, England for live firing practice and the theory of LCT (R)s. Other

officers in charge, assistant officers and key ratings, while

awaiting the arrival of their own craft, completed similar training aboard the

366 and 368. Officers and selected ratings attended HMS Northney for radar training on British 970 and QH sets,

while other officers trained on the Brown Gyro compass

or continued training ashore at Base II.

The slow rate of delivery of the craft

was frustrating. I made numerous trips to see the Officer in Charge of Major Landing Craft at Troon,

in Ayrshire and in Glasgow in an effort to expedite delivery.

By the end of December 1943, the ‘Special Support Group’ became

known as ‘Gunfire Support Group, 11th Amphibious Force’ under the

overall command of Captain L S

Sabin, USN, with me as executive officer or

second in command. On February 6th, 1944,

additional officers and men arrived from the United States,

bringing the complement to over 2000

officers and men manning LCT (R), LCG (Landing Craft Gun) LCF (Landing Craft Flak)

and LCP (L) (Landing Craft Personnel (Large)), which would be deployed as

smoke-layers during the assault phase.

The entire group was, effectively an experiment in a new type of naval

warfare. The need for close inshore fire support for landing operations had been

identified in past amphibious invasions, including the

disastrous Dieppe Raid of August 1942. Heavy

naval gunfire from cruisers, destroyers and battleships,

while effective at direct and indirect targets often

miles inland, could not provide the close quarter support once the infantry had landed.

Converted landing craft with

their shallow draught were able to provide support close into

the landing beaches to fire on enemy positions. This

close quarter support for landing troops was vitally important

and the LCGs were aptly described by the BBC as 'mini battleships'.

Each type of craft performed a specific function. LCT

(R)s were designed to lay down an intensive barrage

of 1000 + explosive rockets just

prior to the initial assault waves landing, Flak craft were designed to cover

the flanks and to give air protection, as well as giving fire support against

machine gun nests on the beach, while Gunboats would fire on specific targets on

the beaches prior to H-Hour. After H-Hour they gave

close fire support against pill-boxes and other troublesome

gun emplacements.

A later addition to the group was the US Navy Mk5 LCT(A)’s or Landing Craft Tank (Armoured).

Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing craft Association adds;

The Mk5 LCT were American built tank landing

craft. They began arriving in England during 1942 and later many were carried in whole or

part by USLSTs and dropped off in England to be assembled or crewed. Prior to D-Day, close

to 160 had served with the Royal Navy under Lend-Lease and were dispersed amongst numerous LCT

flotillas. To separate them from their American sister Mk5 LCT, the British craft

had a 2 added in front of their original US Navy pennant number, thus, British

Mk5 LCTs carried pennant numbers in the 2000 series.

At various times 48 LCTs

were converted for specialist

duties and re-designated LCT (A)

(Armoured), LCT (HE) (High Explosive) and LCT (CB) (Concrete Buster).

The LCT (A)s

were fitted with a firing platform to the fore of the tank deck,

allowing the

tanks carried in the first assault waves to fire over the

LCT

(A)'s bows as they approach

the landing beach. In addition to the firing platform or ramp,

the LCT (A)s carried increased armour plate to the bows, bridge and wheelhouse

sections. Having landed, the tanks continued to give close fire support on the

beach.

Prior to D-Day, some 26

LCT

(A) conversions were lent back to the US Navy under ‘Reverse

Lend-Lease’.

It was these craft that became part of the Gunfire

Support Group 11th Amphibious Force. On the morning of D-Day,

distributed

across Omaha and Utah beaches, the

landing craft assigned to Omaha

delivered the

tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, while the craft assigned to Utah delivered the men of the 70th Tank Battalion. All the tanks carried

in by the two groups having the capacity to fire afloat.

The LCT(A) (HE) assigned to the groups were as follows: Utah beach Tare

Green sector - 2310, 2402, 2454, 2478; Uncle Red sector:- 2488, 2282,

2301, 2309. Omaha beach: Dog Green sector:- 2227,

2273; Dog White

sector:- 2050, 2276; Dog Red sector:- 2124, 2229; Easy Green sector:- 2075,

2307; Easy Red sector:-

2049, 2287, 2425, 2339 and Fox Green sector:- 2008, 2037, 2228, 2043.

Craft shown in blue are listed as War Losses in the assault area.

Each

LCT (R)

was designed to deliver hundreds of 5 inch diameter explosive

rockets on to the landing beaches just before the first assault troops were due

to land. The rockets had the

capacity to saturate an area

around 700 yards wide by 300 yards deep

to destroy enemy beach defences

including mines. Careful handling

and preparation, accurate navigation and precise

timing were vital to avoid hitting the assault troops on their final

approach to the landing beaches. Each

LCT (R)

was designed to deliver hundreds of 5 inch diameter explosive

rockets on to the landing beaches just before the first assault troops were due

to land. The rockets had the

capacity to saturate an area

around 700 yards wide by 300 yards deep

to destroy enemy beach defences

including mines. Careful handling

and preparation, accurate navigation and precise

timing were vital to avoid hitting the assault troops on their final

approach to the landing beaches.

[Photo;

An LCT (R) - Landing Craft Tank (Rocket) - in

action off Normandy, 6 June 1944. © IWM (A 23937)].

The two craft that fired during

the ‘Duck II’ demonstration

exercises created a great impression,

although one released her rockets far too early. Nonetheless, they proved to

the American observers that the rocket was a weapon which could pulverise a sector

of beach in the final few seconds before troops went ashore.

The proximity of

our own troops approaching the beaches elevated the timing of a rocket barrage

to the highest importance. Experience proved that rockets could

be safely fired when the leading assault wave was some 700 yards from the beach

or the point of impact of the rocket pattern. There were differences between the

British and American use of the LCT (R)s off Normandy. The British fired at H-Hour minus 10 minutes

while the American LCTRs

fired at H-Hour minus 2 minutes at targets slightly inland.

LCT

(R)

Specifications LCT

(R)

Specifications

The LCT (R)s were converted British Mk3 LCTs with a maximum length of 192 feet

and 31 feet across the beam. The standard power unit comprised two Paxman

Ricardo diesel engines giving a maximum speed of 9

knots, with both screws turning to starboard (right). An extra deck was

constructed over the tank space, on which either 972 or 1044 5"

rocket projectiles launchers were welded. The original design anticipated re-conversion of the craft,

so the crew's quarters, officers' quarters and magazines were separated

by canvas bulkheads. In order to make the US craft more comfortable and secure, the canvas was

replaced by steel or wood by their own crews. Home comforts included bunks and

hot water heaters.

[Left; Image from the Admiralty's Green List confirming

disposition of the LCT (R)s of Force O

(Omaha) on Jun 2nd, 1944].

The craft were equipped with 970 Radar, a

British set which swept 360 degrees in azimuth once a

second. Its maximum range was 25 miles

with three and a

half and seven mile range scales. Whilst the primary use

of the Radar was to accurately

determine where to fire the rockets, it proved to be a valuable

navigation aid. Each craft was also equipped with QH, a navigational aid and a

Brown gyro compass.

The 5" rockets were fired electronically by a series of switches in the

wheelhouse. Each switch would fire either 39 or 42 rockets per salvo, depending

on the total number mounted. One group of 36 rockets was wired

separately to provide twelve

salvos of three rockets each for the purpose of ranging.

All the projector tubes were mounted at a 45 degree angle to the waterline and all

pointed forward. The target area was covered by pointing the craft’s head at the

target, determining the range by radar and/or ranging salvos. The firing of salvos,

with a pre-determined short time interval between them, gained the desired depth of

pattern. The width of the pattern was 700 yards and could not be adjusted. The

depth of a complete broadside of 24 salvos could be achieved within the range of 300 to 1000 yards, or even more, if required.

A round consisted of three partitions, the fuse, projectile and propelling

unit. A complete assembled high explosive round was three feet in length and

weighed 59 pounds, 7 pounds of which was poured high explosive (TNT and Emitol).

The range of a high explosive round was 3580 yards. Incendiary rockets with a

range of 3900 yards were provided for ranging. Smoke rockets were also

available.

The LCT (R) had

several deficiencies. Extreme accuracy in navigation and a very steady course

was essential during a firing run. Rudders were very small and the rocket racks

increased the free board making the craft more

difficult to manoeuvre in the wind. ‘Aiming the ship’

was the only way to line up the rockets with the intended

target and more

manoeuvrability would have been desirable. The LCT (R)s, nevertheless, proved to be an

effective weapon. was the only way to line up the rockets with the intended

target and more

manoeuvrability would have been desirable. The LCT (R)s, nevertheless, proved to be an

effective weapon.

The

Convoy

On March 20th, 1944, at Base II, two more rocket ships, Mk3 LCT

(R)s

447 and 448 were assigned to the US Navy. In brief ceremonies, the British flag

came down to be replaced by the American Ensign. On April 2nd, 1944, LCT

(R)

425 joined the group and the following day the craft formed a convoy south to their

permanent base at Dartmouth, England. I was in command of the convoy, which

consisted of three LCT (R)s, two LCFs and three LCGs. The route took us from Roseneath

by Stranraer, Douglas on the Isle of Man, then down the Irish Sea

to Appledore in Devon. Once around Land’s End,

we headed east

to Falmouth and Dartmouth. The 500 mile trip took five days and

was punctuated with many difficulties, including engine trouble, chronic sea-sickness and radio and radar problems.

[Right; Image from the Admiralty's Green List confirming

disposition of the LCT (R)s

of Force U (Utah) on Jun 2nd, 1944].

Maintenance was the most difficult problem to hand.

Without major overhauls there would be no

lasting improvement in the position. The craft were British LCTs

fitted with British equipment and parts, which were

difficult to obtain under the

elaborate and bureaucratic system of

the Reverse Lend-Lease scheme. The maintenance staff worked day and night when material became available,

although technical equipment such as radios and

Radar, continued to be problematical.

Staff offices were located in the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth around

April 3rd, 1944. My LCT (R) group,

at that time, comprised five craft with the

remainder still to be delivered. Fortunately, their crews were

already at Base II, in Scotland. After

repairs, 425,

447 and 448 sailed to Poole for the Assault

Gunnery School course.

Final

Preparations for D-Day

On April 15th, 1944, the LCT

(R) office was moved from Dartmouth Naval

College to Hunter’s Lodge on the River Dart. Moorings for our craft were assigned close by.

During April, the 366 and 368 took part in

the ill-fated ‘Exercise

Tiger’. Unfortunately they were not allowed to fire on the beaches, because

isolated units of the first wave landed an hour before H-Hour due to a

communications failure. Later that month, 366, 368,

425, 447 and 448 took part in exercise ‘ Fabius 1.’ The first

wave consisted of LCT (A)s and LCTs carrying DD tanks (Sherman Duplex Drive tanks,

swimming tanks).

The original plan was

that the LCT (R)s were to open fire

when this wave was 300 yards from the shore but this was later deemed to be too

close for safety. Some difficulty was experienced in navigating through the

transport area to the correct firing position. LCT (R) 425 became lost in the

transport area and did not open fire at all and 447 failed to reach the

transport area. However, the three remaining craft successfully fired their

volleys and demonstrated once again the effectiveness of the rocket fire, which

completely obliterated their theoretical targets. The original plan was

that the LCT (R)s were to open fire

when this wave was 300 yards from the shore but this was later deemed to be too

close for safety. Some difficulty was experienced in navigating through the

transport area to the correct firing position. LCT (R) 425 became lost in the

transport area and did not open fire at all and 447 failed to reach the

transport area. However, the three remaining craft successfully fired their

volleys and demonstrated once again the effectiveness of the rocket fire, which

completely obliterated their theoretical targets.

On May 6th,1944, LCT

(R)s

423, 450, 452 and 464 arrived in Dartmouth. These craft were much newer and

required much less maintenance, although radar and radios were

still a problem.

[In this index page from

the Admiralty's "Green List" the prefix US is used for the LCT (R)s

whereas on the disposition pages above no prefix is used. This is most likely

because the "US Eleventh Amphibious Force" heading renders the US designation

against individual craft superfluous].

They

immediately embarked upon a number of exercises to bring the crew and craft up

to operational standard with a series of firing exercises on the Slapton Sands assault area.

The British gunnery school at Poole was, by then, closed but these training

exercises, which we undertook on our own initiative,

proved beneficial. Emphasis was placed on timing and accurate ranging using test

salvos and radar.

On May 17th, 1944, LCT

(R)s 439, 473 and 482 arrived in Dartmouth. We

were still missing 481 and 483. Training continued throughout May and every craft

was given a complete operational check. There was a noticeable increase in

activity and intuitively we knew that D-Day was at

hand. Our skills were fine tuned with daily firing runs into mock enemy beaches.

Two sets of rockets were loaded onto each craft - one for the racks and the other for the magazine. Other materials were taken

aboard and detailed logistics and intelligence plans were received. All sorts of

publications about our mission were distributed.

It was now

glaringly obvious that the invasion date was near. Our craft were assigned to

two forces, 366, 423, 483, 447, 450, 452, 464, 473 and 482 were assigned to ‘Force

Oboe’ under Rear Admiral Hall and 368, 425, 439, 448 and 481 were assigned to

‘Force Uncle’ under Rear Admiral Moon.

Late in May, ‘Third’ officers were assigned to each of the craft. Those

officers who had served with gunfire support craft in other capacities were sent

to radar school and joined the LCTRs primarily as radar officers. However, most

of their duties were on deck but they all proved to be a valuable addition to

the efficiency of the group. The allocation of the ‘Third’ officers to their

craft was as follows; Ensign F D Michael to 439, Ensign R E Worthen to 366, Lt

(jg) R

W Bennison

to 368, Ensign R L Palmer to 423, Ensign R M Costello to 425, Ensign G D Soule

to 447, Ensign G L Hershman to 448, Ensign D G Swallow to 450, Ensign J C Cavness

to 452, Ensign C H Easley to 464, Ensign G P Sherman to 473, Ensign P T Wilson

to 481, Ensign J J Lassiter to 482 and Ensign S S Rough to 483. Ensign Michael and Lt

(jg) Bennison went aboard the 439 and 368 for temporary

duty. Late in May, ‘Third’ officers were assigned to each of the craft. Those

officers who had served with gunfire support craft in other capacities were sent

to radar school and joined the LCTRs primarily as radar officers. However, most

of their duties were on deck but they all proved to be a valuable addition to

the efficiency of the group. The allocation of the ‘Third’ officers to their

craft was as follows; Ensign F D Michael to 439, Ensign R E Worthen to 366, Lt

(jg) R

W Bennison

to 368, Ensign R L Palmer to 423, Ensign R M Costello to 425, Ensign G D Soule

to 447, Ensign G L Hershman to 448, Ensign D G Swallow to 450, Ensign J C Cavness

to 452, Ensign C H Easley to 464, Ensign G P Sherman to 473, Ensign P T Wilson

to 481, Ensign J J Lassiter to 482 and Ensign S S Rough to 483. Ensign Michael and Lt

(jg) Bennison went aboard the 439 and 368 for temporary

duty.

[Photo right; Ensign J C Cavness of US LCT R 452].

During the last week of May, all craft in Force 'Oboe' were ordered to Poole and

the craft of Force 'Uncle' to Salcombe to prepare for the invasion. LCT (R)s 481 and

483 arrived loaded and ready to go at their respective ports of embarkation on

June 1st. The crews of both craft had passed through gunnery school

on other craft but they did not fire a rocket from their own craft until the

invasion.

The Invasion -D-Day

On June 3rd, all LCT

(R)

personnel were briefed on their role in the coming invasion.

Maps of our landing beaches were issued, landmarks and targets

identified and intelligence reports

issued, all set within the wider context of the task ahead. It was especially important that

the LCT (R) officers familiarised themselves with the terrain, landscape and landmarks of the beach

to accurately pin point their target. As an aid, a PPI

screen prediction was added to the radar devices,

which they could compare with the live PPI screen display as they approached

their landing beach. When the two images matched

they were ‘on target’.

Frequent briefings and

further study of the meticulous and

detailed plans followed. At 0300 hours on the morning of June 4th,

1944, after a final briefing to my men, the craft of Force

'Oboe' sailed in

convoy for France. The craft of Force 'Uncle' had sailed at 1600 hours on the

afternoon of June 3rd, however, the weather had

deteriorated and all ships were ordered back to their starting points. The LCT

(R)s of ‘Oboe’ had LCMs in tow carrying demolition units and these greatly

hampered ship handling. The ‘Uncle’ LCT (R)s had LCP (L)s in tow. The craft

for the ‘Oboe’ convoy returned to Poole

and the craft of the ‘Uncle’ convoy put

into Portland.

The weather had improved a

little when the convoys

got underway for the 2nd time on June 5th and headed for

Normandy. Manoeuvering the unwieldy gunfire support craft

was very difficult in the rough

waters of the English Channel. At approximately 0500 hours on the morning of June 6th,

1944, the convoys arrived at their respective transport areas, where the tows

were detached. 425 had fouled her screws and was

assisted down the mine

swept lanes in convoy towards the line of departure. This was

the starting point for our final approach to our designated beaches and at approximately 10,000 yards offshore the LCT

(R)s formed up line abreast and began their run for the beach. H-Hour was set

at 0630 hours.

.jpg) All

craft discharged their rockets. The first craft to

engage the enemy was 366 at H-Hour-7 minutes,

while LCT (R)s 450 and 447 fired when the LCT (A)s were 500 yards from the

beach at H-Hour+2 minutes. The other craft

discharged their rockets at intervals between those times.

Reports later submitted

by

the officers in charge described the action; All

craft discharged their rockets. The first craft to

engage the enemy was 366 at H-Hour-7 minutes,

while LCT (R)s 450 and 447 fired when the LCT (A)s were 500 yards from the

beach at H-Hour+2 minutes. The other craft

discharged their rockets at intervals between those times.

Reports later submitted

by

the officers in charge described the action;

-

Time of firing H-7 minutes to H+2 minutes.

Estimated position of the

first troop carrying assault craft

varied between 2000 yards and 200 yards from

the beach

-

Officers believe they fired on target in all instances.

-

Time taken to

reload varied between between 9

and 19 hours. The difference was

accounted for by random events, including the loss of anchors, rockets

stuck in boxes and large numbers of misfires requiring the

removal of the projectiles.

-

The 970 Radar and the PPI Predictions were

deemed successful by all craft.

All craft fired 'ranging salvos'

but poor visibility prevented

accurate

calculation of their points of impact. With the exception of LCT R) 366, ranging

salvos were used only to ‘check’ the accuracy of the radar.

-

[Photo courtesy of Becky Kornegay].

-

The extremely

shallow water in the vicinity of several beaches added to the

difficulty in ranging salvos, because the

rockets could easily have exploded

short of the beach in the water,

giving the impression they had reached the beach. All craft,

with the exception of the 366, therefore, fired by radar at the pre-determined range.

Firing positions were

calculated

with reference to landmarks and fixes, obtained in some instances by QH and in

others by 970.

-

There were no casualties to either the craft or the personnel

and no craft

fired a second load of rockets. On June 9th, ‘Oboe’ LCT

(R)s returned to

Poole and on June 12th, ‘Uncle’ LCT (R)s returned to Portland. The US Navy

LCT (R) Group had fired 12,605 rounds of high explosive ammunition and 326 rounds

of incendiary on to the beaches of Normandy. Their mission was considered

a success.

After a week in the 'return convoy' ports, the LTC

(R) group returned to

Dartmouth. There were no orders, so we took the opportunity to

carry out routine maintenance repairs.

The

Mediterranean

On June 29th, 1944,

orders came to prepare nine craft for operations in the Mediterranean area.

All nine craft were painted American Battleship Grey,

the engine tops were

overhauled, new American TCS radios were installed and radars

were checked and

repaired as required. Provisions were taken on board and the fire fighting equipment

greatly improved. Because US bases did not carry

spares for our British LCT (R)s, we stocked up with more spares than usual. Time was

tight but, with close co-operation and coordination between the base

and the craft, work progressed apace, including dry dock

repairs to damaged hulls. Ensigns C H Lockwood and B

T Geckler joined the group as ‘Third’ officers

on 439 and 368. The entire staff moved aboard and we were

ready to sail. The intense effort had taken just one week.

On July 7th, 1944, our group sailed to Plymouth to join

ten British manned LCT (R)s for the passage to the Mediterranean

and 4 days later the commanding officers were briefed

on the convoy. It comprised the combined British and US Navy LCT

(R)s, two

destroyers and five tugs. After the briefing, Admiral J L Hall addressed the US LCT

(R)

officers in charge. He expressed gratitude for a job well done off the Normandy

beaches, being aware of the many

difficulties and problems experienced. He requested the officers in charge to convey

his appreciation to the officers and men.

On July 12th,

the convoy set off for Gibraltar and the trip was

comparatively uneventful. There were submarine alerts but no signs of enemy aircraft. Gibraltar was

sighted on July 20th and new orders were received for the USLCT (R)s to

continue to Oran, where we arrived on July 21st

thus completing the longest non-stop trip ever attempted by such

craft. The British elements remained in Gibraltar. On July 12th,

the convoy set off for Gibraltar and the trip was

comparatively uneventful. There were submarine alerts but no signs of enemy aircraft. Gibraltar was

sighted on July 20th and new orders were received for the USLCT (R)s to

continue to Oran, where we arrived on July 21st

thus completing the longest non-stop trip ever attempted by such

craft. The British elements remained in Gibraltar.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

The craft functioned surprisingly well, although

two suffered air locks in their fuel supply

lines and were taken under tow until repairs could be

made. Of the 24 craft, only four required a tow at any time

and we completed the10 day trip at an average speed

of seven and a half knots, made possible by favourable

weather and sea conditions.

On July 23rd, we set off for Bizerte

without tugs or escorts. LCT (R)s

366 and 450 broke down one day out and

they returned to Oran under tow, while the

rest of the convoy continued for Bizerte with 473

taken under tow at some point, when

one of her two main engines broke down. There was a heavy sea on the night of July

25th, so the convoy resorted to tacking for twelve hours

to keep the craft more stable. All

twelve craft arrived in Bizerte Road at 2300 hours on July 28th,

1944 and entered Bizerte Harbour on July 29th, in need of

extensive repairs.

However, before major overhauls

could be carried out, the most serviceable craft sailed to Naples between the 1st and 5th

August with others following on in

small groups as they became operational. LCT (R)s 366 and 450 arrived in Bizerte on

August 3rd, by which time 366 needed two new engines and the 450’s

ballast tanks were leaking into her fuel tanks.

In Naples, the briefings for the new campaign began with little time for thorough

scrutiny of the plans. However, our previous experience

off Normandy made the process

easier to understand.

The craft had sailed without their complement

of rockets for damage control reasons but supplies, thought to have been in

Naples, fell short of our requirements.

LCT

(R)s 366, 450, 481 and 423 sailed to the Pozzuoli staging area on August 9th

unloaded. The 366 had two new engines installed and the 450 had filled

her ballast tanks with fuel oil to make the trip. All craft arrived at the Pozzuoli staging area in operational condition. En

route to Ajaccio, 366, 423, 450 and 481 left the convoy for Maddalena to load. Fuses needed by other craft were flown to Ajaccio and all the

craft left Ajaccio loaded and in operational order. LCT

(R)s 366, 450, 481 and 423 sailed to the Pozzuoli staging area on August 9th

unloaded. The 366 had two new engines installed and the 450 had filled

her ballast tanks with fuel oil to make the trip. All craft arrived at the Pozzuoli staging area in operational condition. En

route to Ajaccio, 366, 423, 450 and 481 left the convoy for Maddalena to load. Fuses needed by other craft were flown to Ajaccio and all the

craft left Ajaccio loaded and in operational order.

[Map courtesy of Google. 2019].

Operation

Dragoon - The

Invasion

of Southern France

At 1930 hours on the evening of August 13th, 1944,

the first assault convoy got underway for France. The weather for the entire

trip was favourable and the movement plan was accomplished, although the convoy

speed of 4-5 knots was too slow for our flat bottomed craft to keep

good station.

LCT (R)s 366 and 425 were assigned to Blue Beach and on Green Beach 368, 423,

447, 452, 482 and 483 were assigned to the original assault in the Camel area. LCT

(R)s 439, 448, 450, 464, 473 and 481 were assigned to Red Beach for the Z hour

assault. They were joined by the reloaded LCTR 425 and a number of British

craft.

The craft on Blue Beach reported

no opposition. Lieutenant J C Cohen USNR, commanding 366, fired at H-5 minutes

to cover a ‘rather slow first wave’. Lieutenant (jg) R E Ellicker, commanding

425, fired at approximately the same time. Both craft believed themselves on

target although haze and dust on the beaches made a positive sighting impossible.

Superficial damage and fires were caused aboard both craft by the intense heat

of the propelling charge. The craft on Blue Beach reported

no opposition. Lieutenant J C Cohen USNR, commanding 366, fired at H-5 minutes

to cover a ‘rather slow first wave’. Lieutenant (jg) R E Ellicker, commanding

425, fired at approximately the same time. Both craft believed themselves on

target although haze and dust on the beaches made a positive sighting impossible.

Superficial damage and fires were caused aboard both craft by the intense heat

of the propelling charge.

The six craft on Green Beach fired approximately as scheduled. Reports

indicated that 447 of Lt W L Quest fired at H-9

minutes, 452 of Lt W B McCown fired at H-6 minutes, 423 of Lt (jg) W S

Caldwell fired at H-5 minutes, 483 of Lt (jg) R H Tucker fired at H-5 minutes

and finally Lt G A Karlsen, commanding the 368, fired at H-Hour. The 368

was on the flank but did not fire over the troops. Sporadic enemy gunfire was

observed but all fell short of the craft.

The radar on 447 stopped

working by H-1 hour and she was forced to rely on

ranging salvos, which were difficult to observe on a hazy beach. The 482 reported

strips of light metal resembling tinfoil

falling from the sky, which fogged the PPI

picture but the problem cleared up before firing. The remainder of the craft

recorded no problems. The beaches were again obscured by the pre-H-Hour

bombardment and the precise impact locations could not be

confirmed from

the firing range. Craft in the boat lanes experienced difficulty in standing

clear of the second wave.

The craft assigned to Red Beach formed up and proceeded to the line of

departure in order to carry out the Z Hour assault at 1400 hours. Once there,

they stood by for approximately one hour between 1345-1445, awaiting the

completion of an unsuccessful attempt to destroy obstacles on the beach by Apex

boats. During this time, they were subjected to sporadic gunfire, which came

extremely close. However, all the projectiles fell

short, suggesting that the shore

batteries were firing at their extreme range. Shrapnel fell on the

decks of all the craft involved and Seaman Richard Charles Syers, serving with

LCTR 439, was hit by a nearby

burst at about 1430 hours. He

was the only casualty in the group. Upon receipt of the order to proceed to

Green Beach, the LCT (R)s returned to the transport area and stood by.

At about 1430 hours on D+1, all LCT

(R)s

received orders from LCH 240 (Landing Craft Headquarters 240) for

onward routing and at about 1630, the craft sailed in a nine knot convoy, for Ajaccio.

However, after 7 hours, they were all ordered to return to Red Beach, because an

escorting vessel had become detached during the night. By the time the craft set

off for a second time, both 448 and 452 had problems with one of their engines

and were taken under tow. All craft arrived safely in Ajaccio on August 19th. However, after 7 hours, they were all ordered to return to Red Beach, because an

escorting vessel had become detached during the night. By the time the craft set

off for a second time, both 448 and 452 had problems with one of their engines

and were taken under tow. All craft arrived safely in Ajaccio on August 19th.

[Photo of US LCT (R) 439,

courtesy of Becky Kornegay].

The LCTRs remained for a day and then sailed for Bizerte, arriving there on

September 1st. At Bizerte, repairs were

undertaken and all craft were repainted. They were not

returned to England as expected for

transfer back to the Royal Navy, instead they were transferred to the British base at Messina and all US Navy

personnel repatriated. On October 4th, 1944, all the LCT

(R)s were

returned to the Royal Navy.

Conclusion

Following the return of our craft back to the Royal Navy, my officers and men

returned to America by ship. I flew back to Washington for a new assignment,

where the

Bureau of Naval Personnel appointed me to

set up a training programme for crews

of the new LSM (R) rocket ships being built for the US Navy.

All of my

former officers and crews were ordered back to Little Creek for training.

I was later assigned as Flag Lieutenant to Admiral Lowrey in San Diego, who

was to command the amphibious forces for the invasion of Japan. The end of the

war in 1945 resulted in my being returned to inactive duty on September 14th

1945.

The use of British rocket craft proved of great value to

the US Navy. In no small measure, they made a significant contribution, furnishing support

for our troops landing both in Normandy and in Southern France.

The job of recruiting

and training personnel for our

British rocket ships and the development of the associated administrative

organisation was challenging, as inexperienced personnel worked in unfamiliar

craft within a limited time. It required

close co-operation between the groups and their

British counterparts. With the successful completion of its missions, the LCT

(R) group, the first of its type in the US Navy, considered its

task was well done.

Key points in the author's naval service

Pearl Harbour. 1941. He was on the first US Navy vessel that witnessed

a Japanese midget submarine in Pearl Harbour and later the attack on December 7th,

1941.

D-Day-Normandy. June 6th. 1944.

Group Commander of all US Navy Rocket Ships (LCTRs) to fire on to the

beaches just 300 yards ahead of the first assault wave.

D-Day Southern France. August 1944.

Still Group Commander of all LCTRs to fire ahead of the first assault wave.

LSMR Programme.

First US Naval Officer attached to a new programme to

train men in the use of a new generation of rocket ships built for the invasion of Japan.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on

our 'Combined Operations Books' page. They, or any

other books you know about, can be purchased on-line from the

Advanced Book Exchange (ABE). Their search banner link, on our 'Books' page, checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Just type in, or copy and paste the

title of your choice, or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Correspondence

Mr. Slee,

US LCT (R) 483

My late uncle, Charles R. Murphy served aboard the US LCT (R) 483 at the

time of the Normandy Invasion, etc. Briefly his story is as follows.

He enlisted in the Navy on June 17, 1943, but he "misstated" his actual date

of birth as June 16, 1926 instead of the actual date of

June 16, 1927. After boot camp, he attended electricians

school and then assigned to the USS LCT (R)

%20483%20Crew_small.jpg) 483 just in time for D Day. In

other words, he was 16 years of age at the time the ship was off Omaha

Beach. He told me that an interesting aspect of his time on the ship was that

they had not fired their rockets before D Day itself and they had to move in

close to the beach to fire the rockets, then he saw the Army troops being

ferried toward the beach as they withdrew from the area. 483 just in time for D Day. In

other words, he was 16 years of age at the time the ship was off Omaha

Beach. He told me that an interesting aspect of his time on the ship was that

they had not fired their rockets before D Day itself and they had to move in

close to the beach to fire the rockets, then he saw the Army troops being

ferried toward the beach as they withdrew from the area.

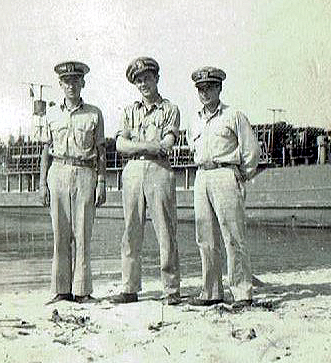

[Photo;

Part of Crew, USLCT

(R) 483.

(L-R),

Top Row W. Snell, S 1/c, Bill

Cunningham, SY c, N. White, S 1/c, H Ricks, MoMM 2/c, B. Brennan, RM 3/c, R.

Jones, GM 2/c. Second Row

LTjg R.H. Tucker, D.C. Hurley, SM 3/c, Davy Turner S 1/c,

C. Orlando S 1/c, Jim Finn, QM 3/c, ENS E.V. Mack.

Third Row Paul Hannah, MoMM

3/c, R. Perkins, Cox., C. Murphy, F 1/c, Tom Derr, MoMM 3/c].

After the LCT's were turned back over to the British Navy, he was assigned

to the USS Clarion River [LSM (R) 409], rode it to the Pacific

theatre and was aboard this ship when the war ended. At the time, he was an

Electrician's Mate 3rd Class.

%20483%20II_small.jpg) After the war, he knocked around the San Diego area for a while, then joined

the Army just in time to be sent to Korea where his outfit, the 163rd

Artillery, was over-run by North Koreans. He was reassigned to Pusan in the

Quartermaster Corps and decided to stay in the Army. He served in Germany,

two tours in Vietnam (where he was awarded the Bronze Star), etc. and retired

as a Sergeant-Major. He died on May 17, 2017 in North Little Rock, AR. He

will be buried with full military honors on June 16, 2017 on what would have

been his 90th birthday. After the war, he knocked around the San Diego area for a while, then joined

the Army just in time to be sent to Korea where his outfit, the 163rd

Artillery, was over-run by North Koreans. He was reassigned to Pusan in the

Quartermaster Corps and decided to stay in the Army. He served in Germany,

two tours in Vietnam (where he was awarded the Bronze Star), etc. and retired

as a Sergeant-Major. He died on May 17, 2017 in North Little Rock, AR. He

will be buried with full military honors on June 16, 2017 on what would have

been his 90th birthday.

[Photo; taken from

US LCT (R) 483, possibly on D Day or some other major landing or training

exercise in view of the numbers of vessels in view].

As an aside, I have the flag of the US LCT (R) 483 that was flying on D Day.

As he related to me, sometime after D Day, due to the storms and the smoke,

etc. from the rockets, the flag had become tattered and was being replaced.

He asked the Captain for the flag and he sent it home to a sister, who kept if

for years, then returning it to my uncle, who gave it to me this past year. I

have it "framed" in my office in a flag case....indeed, it is stained and

tattered. He had an interesting life and never tired of telling stories from his time

in the Navy and the LCT (R) 483 in particular.

Acknowledgments

These personal recollections of Lt Commander Carr concentrate on

the use of US Landing Craft Tank (Rocket) off Omaha, Utah and Southern France. They were transcribed by Tony Chapman, Official Archivist/Historian of the LST

and Landing Craft Association (Royal Navy) and edited by Geoff Slee for publication on the Combined Operations website

including the addition of maps, Imperial War Museum photos and extracts from the

Admiralty's 'Green List' of landing craft dispositions.

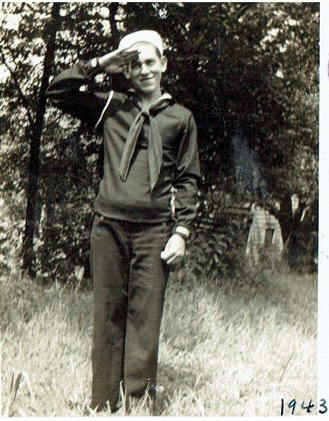

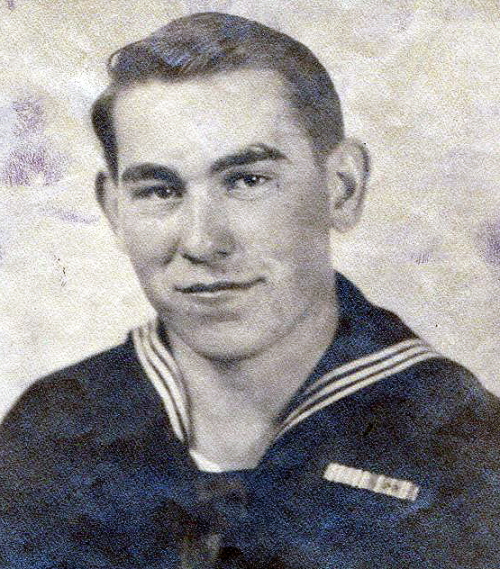

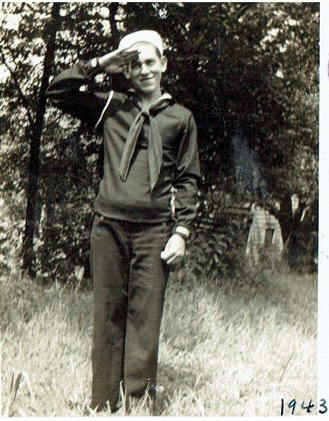

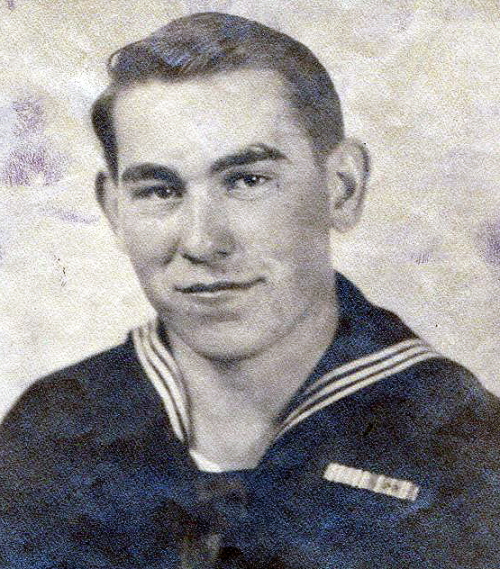

US LCTR Flotilla - Diary Entries of Seaman Ist Class, Jack

Nicholas

Jack

Nicholas S 2/C,

A.T.B. Camp Bradford N.O.B, Unit

King Tent 67,

Norfolk, VA Jack

Nicholas S 2/C,

A.T.B. Camp Bradford N.O.B, Unit

King Tent 67,

Norfolk, VA

Special Support Group,

Nov

22, 1943

Left

Boston 1630 - 1637

men.

Nov

23, 1943. Took Ferry across Hudson River to N.Y. where we went aboard the Queen

Elizabeth. Left over seas at 1530. We seen the statue of Liberty as we left.

Nov

28. We landed in Scotland at 0831, 25 miles west of Glasgow and now waiting to

go ashore

Nov

30. We will go ashore to day for the first time at 0900.

Dec

1. We are ashore now and living in huts. There is sure a lot of pretty places

around here.

Dec

15. We formed our rocket crew and are living in one area.

Dec

25. Had turkey for chow today, and it was pretty good too. Didn’t seem like

Christmas though.

April 9, 1944. We got our rocket ship today, it is about time.

April 13. We took over from the British, it’s now our ship.

April 21. We

left for Dartmouth today.

April 21. We

landed in Lock Ryan at night.

April 22. Isle

of Man. Went

ashore and had a good time.

April 23. Holyhead, North Wales.

April 24. Milford Haven. We

missed convoy so we will have to wait till tomorrow.

April 25. We

went out but we came back into port again.

April 26.

Still in Milford Haven.

April 29.

Arrived in Dartmouth, England. It is sure pretty good weather here, but liberty

is sure lousy. April 29.

Arrived in Dartmouth, England. It is sure pretty good weather here, but liberty

is sure lousy.

May

1. It

was sure a swell day today. We were supposed to go to Plymouth but didn’t.

May

2. We

went to Plymouth today. We will stay there all tomorrow.

May

3.

Worked all day, air alert at 1500.

May

4. Worked all day. Had liberty but didn’t take it. Wrote letters and listened to

music in radio shack.

May

5.

Lippy, Titlow, Mahon took dingy and came back drunk as hell. Old man raised

plenty of hell.

May

6. Left Plymouth 0800 for Dartmouth at 5 pm.

May

7. Went

to Church in Dartmouth.

May

8. Went

on maneuvers but didn’t fire.

May

9th.

Fired rockets for first time. Quite a sight.

May

10.

Fired again, not much else.

May

11. Got

stuck in mud going to sea, turned around and spent eve in Dartmouth.

May

12.

Washed clothes and laid around, didn’t go out.

May

13.

Didn’t go out again.

May

14. Went

out this morning. Air alert 3 am.

May

15. Alert

at 1 pm, also early in morning went out on firing range also in aft.

May

16. In

port-also my birthday.

May

21.

Refueling and taking on fresh water.

May

23.

Started early this morning for Plymouth. Got there in evening and loaded 522

rockets.

May

24.

Started loading rockets early morning and worked all day and part of night. Took

on 2088 rockets and fuses. Was really tired.

May

25.

Finished all loading and slept in aft.

May

26. Early reveille left for Dartmouth. Rough sea, most of the boys got sick but

I didn’t. Saw a mine to close for comfort. Got back early evening and wrote

letters.

May

27.

Didn’t go out today.

May

29. Was

sick all day today with the cramps. We left for Poole early in the morning. Got

there at 2200.

May

30.

Didn’t go out today. Went swimming this afternoon. Sure felt good. I met Reed

today. I sure was glad to see him. He is in LCF3.

May

31.

Still in Poole, didn’t go out today. Went swimming at night.

June

1.

Changed rockets around today. We still didn’t go out. Still waiting for the big

push and sick of this shit barge. June

1.

Changed rockets around today. We still didn’t go out. Still waiting for the big

push and sick of this shit barge.

June

2. Went out to calibrate radar sets and anchored, anchor chain broke and we

were adrift, what an experience. Hurley took all of our money.

June

3.

Weighed anchor for invasion but gale forced us to postpone operations for 24

hours.

[Photo; Rocket launching racks].

June

4.

Weighed anchor at 0200 for France. Passed convoy of 30 liberties.

June

5. In

middle of channel on way to France. The craft behind us broke loose and is under his

own power.

June

6, 1944 Tuesday.

D-Day. Wagons opened up at 6:00. H-hour at 6:30. Went into beach under fire and

tanks fired over heads. We fired 1044 rockets at our objective. It was

demolished. I sure would have hated to be on that beach.

June

7.

Jerry over last night and at daybreak, troops are moving inland over the hill.

June

8. We

started back for Jolly ole England and got in Poole last night and anchored out

of the harbor.

June

9. Came

into port this morning and took on fuel and then we anchored. Heard news

tonight, sounds pretty good.

June

10. Stayed in port today although we were supposed to go out and fix compass.

Went ashore at Poole to get supplies. Had chicken today, listened to radio tonight.

June

11.

Didn’t do a damned thing, I heard Jack Benny on radio.

June

12. We

had to kill Tuffy today, he took a fit, we put him in a sack and threw him

over, and then we shot him. I also got two letters today too.

June

13.

Nothing happened today. Gee we sure miss Tuffy.

June

14.

Nothing happened today. It rained all morning. Fixed radio in quarters this

afternoon.

June

15. We

left for Dartmouth at 14:30. We are still under way at 24:00.

June

16. We

got here in Dartmouth at 02:30. We anchored out until daylight and then we came

in, went ashore and got a haircut, shower and went to the movies. June

16. We

got here in Dartmouth at 02:30. We anchored out until daylight and then we came

in, went ashore and got a haircut, shower and went to the movies.

June

17.

Didn’t go out. Went swimming this afternoon. Water was pretty cold. Had guard

from 2000 till 2400 tonight. Wrote a letter to June Brown.

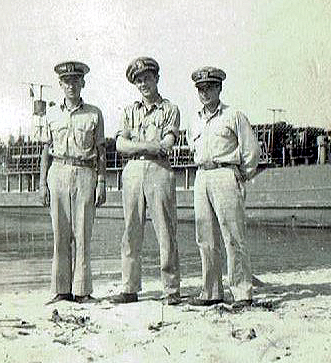

[Photo; US Crew of LCT (R)].

June

18.

Didn’t go out today, just laid around in the sun. Had chicken for dinner today.

Was pretty good. Sure is a lot of scuttle but going around.

June

19.

Didn’t go out today, went swimming this afternoon and got sunburned. It hurts a

little now but I think it will be all right tomorrow. I got some mail today, the

first for some time.

June

20. Went out on liberty today to Torquay. It sure is a pretty

nice place, came back drunk.

June

21.

Didn’t go out today – started to paint our quarters blue. It sure is a big job,

but it looks much better. Had a little hangover from yesterday.

June

22.

Didn’t go out today, washed some clothes. We walked two

girls home. We started to defuse the rockets today.

June

23.

Didn’t go out – we were defusing rockets all day today. Also got a new dingy and

took some pictures too. I wrote some letters tonight.

June

24. Went on liberty at 1300. Didn’t get back until next morning. Had

a very good time on liberty and went to Newton.

June

25. Got in at 0800. Didn’t do anything but sleep. Wrote a letter

to Mom and Bill.

June

26.

Didn’t go out, took rockets below deck out of the racks. Took fuses away and

then started to scrape. Went on liberty. June

26.

Didn’t go out, took rockets below deck out of the racks. Took fuses away and

then started to scrape. Went on liberty.

June

27.

Didn’t go out, rained all day long, scraped paint all day.

June

28.

Didn’t go out, scraped paint till 4:30 and then went on liberty. Saw picture

'Uninvited'. It was very good.

July

3. We

are still at the docks getting repaired. I sure would like to know where we are

going. The ship is painted all blue now.

July

5-6.

Fixing up ship.

July

7. We

left for Plymouth at 1300. Got there at 0800. I don’t know how long we will be

here.

July

8. Crew

went out to check compasses me and two other men and an officer went after

supplies. We were gone from 0800 till 2400. Lost my dog tags.

July

9.

Didn’t go out, had the dishes to do today. It was raining all day.

July

10. We

are still here in Plymouth, no liberty. We are waiting to pull out for

somewhere. God only knows where. All we do is lay around and play cards and

read. We were supposed to leave today but it was cancelled for 24 hours. So we

will leave tomorrow.

July

12. Well

we left at 0800 this morning for Gibraltar, it will take us about 12 to 14 days.

The trip will be 1400 miles. There are 14 American rockets craft and 10 limie rocket

craft.

It was nice and calm today.

July

13. 2nd day of trip, was slightly rough today. We are standing 3 on and 6 off.

Took a picture of a sea hawk today. It was sitting right on our rails. About

three guys were sick today. I never thought we

would sail the Atlantic ocean in an LCT. We are about 150 miles off the coast of

France now.

July

18.

Smooth sailing, Was out in the sun all day, can stand watch at

night in skivy shirt. Course 136. Expect to be in Gibraltar in two days.

July

19.

Still smooth sailing, they changed the orders today. We will go to Oran instead

of Gibraltar. I don’t think we have enough fuel to get there, but my sunburn

sure hurts.

July

20. We

ran out of fuel and are being towed by a tug. We went through the Strait of Gibraltar

this afternoon at 1200. Gibraltar was on our left and Spanish Morocco, North

Africa on our right, the water here in the Mediterranean is dark green, where it is sort

of dark blue in the Atlantic. We are still sailing, expect to be there late

tomorrow. July

20. We

ran out of fuel and are being towed by a tug. We went through the Strait of Gibraltar

this afternoon at 1200. Gibraltar was on our left and Spanish Morocco, North

Africa on our right, the water here in the Mediterranean is dark green, where it is sort

of dark blue in the Atlantic. We are still sailing, expect to be there late

tomorrow.

July

21. We finally got to Oran, we were towed to Gibraltar and then refueled and

we came under our own power to Oran. I had dished today also. It sure is nice

here. Went swimming as soon as we anchored but they chased us out later.

July

22.

Still in Oran, went ashore today at 1300. Came back at 2200. It sure is a crummy

place, all natives or Frenchman. I bought a ring as a souvenir for 50 franks.

The beer tastes like it had salt water in it, but it was good and cold, couldn’t

get post cards.

July 23.

Slept all morning, got supplies in the afternoon and we are underway now for

Bizerta, North Africa. We left at 1500. Don’t know how long it will take us to

get there.

July

24. Last

night it got pretty rough as we turned back to Oran. We lost three ships. We got

back to Oran at 11:30. It was dark so we couldn’t go in and anchor, we roamed

till morning.

July

25. We

left again for Bizerta this morning, boy I am sure sick of this ship.

July

26. We

ran into rough weather again but didn’t turn back, we lost 1 ship. We left three

back at Oran so there are only 10 of us now.

July

27. It

has been very calm weather today, everything is with us, wind, swells and

current. We ought to be in Bizerta by Sat. I hope. If I don’t soon get a haircut

I’ll need a violin. July

27. It

has been very calm weather today, everything is with us, wind, swells and

current. We ought to be in Bizerta by Sat. I hope. If I don’t soon get a haircut

I’ll need a violin.

July

28. We

arrived in Bizerta about 10:00 this morning. It sure is a beat up place, ships

sunk in the harbor and building sunk wrecked by bombs.

July

29.

Greased racks and went to the show at night.

July

30. We

laid around all day long and didn’t do anything. I went to the movie at night.

July

31. We

were still greasing racks. Went up to the red cross for a while this afternoon.

Went to the show at night.

August 1. Pay

Day. I drew $64 today. I am going to send Mom 50 dollars. We got paid in

American Gold seal money. Sure is good to have American money again.

August 3.

Cleaned triggers and went to the show and beer line at the base.

August 4. Got

underway for Italy at 0800 this morning, calm weather.

August 5. Off

Sicily at 1100, 90 degree turn to port at Palermo. Sailing NE. All’s well in

Tyrrhenian Sea.

August 6.

Dropped hook at Naples, Italy at 0900. Weighed anchor and went inside harbor at

1100.

August 7.

Liberty, port side went to Naples for souvenirs.

August 8.

Brought stores aboard and loaded 36 range rockets aboard.

August 9.

Weighed anchor, in large assault convoy LCTS. We left convoy and proceeded on to

load rockets, 481 was hit with a Italian tincan.

August 10. Alls

well sailing north west. Tied up on Madolelenid(?) Island at 21:00. August 10. Alls

well sailing north west. Tied up on Madolelenid(?) Island at 21:00.

August 11. Took

on full load of rockets and fused them. Took on water and stores in the evening.

[Photo; LCT(R) 423 Officers - Lt Caldwell, Eng TJ Hurley +?]

August 12.

Shoved off to meet invasion convoy at Corsica. 06:00 arrived in Ajaccio, Corsica

at 15:00.

August 13.

Shoved off from Corsica with entire beach head force at 1800. D-day is Tues.

August 14.

Sailing for France. Can hear heavies bombing France.

August 15.

D-Day.

Bombing, naval bombardment of beach. We let the rockets go at 0800. We are

waiting in the transport area now. Someone killed a 439 sailor, buried on

beach.

August 16. We

had an air raid last night. We were tied up together, five of us at night. We

got orders to join convoy. After joining convoy, they told us that we were

needed again so we are heading for beach now.

August 17. We

got back to beach this morning and found out that they didn’t need us, so we are

heading for port Ajaccio at 1300.

August 18. We

got here in Ajaccio this morning at 1130. We brought the ship right up on the

beach. It was a bad storm this afternoon. We will probably be here a couple of

days.

August 22. Went

swimming again today, that’s all I have been doing the past week. I wish I knew

when we would leave this place.

August 30. Well

we are finally leaving. We started for Bizerta at 12:00 this afternoon, expect

to be there Fri. Very calm weather. I hope we turn them (our LCTRs) over (to the

British) in Bizerta.

August 31 to Sept 9. We

are still here in Bizerta. I hope we will turn them over soon.

September 20.

Turned LCTRs over to the British at Messina, Sicily.

October 20. Went

aboard the U.S.S. General Meige for New York.

October 23. Stop

again in Oran for more passengers. October 23. Stop

again in Oran for more passengers.

October 30.

Arrived in New York.

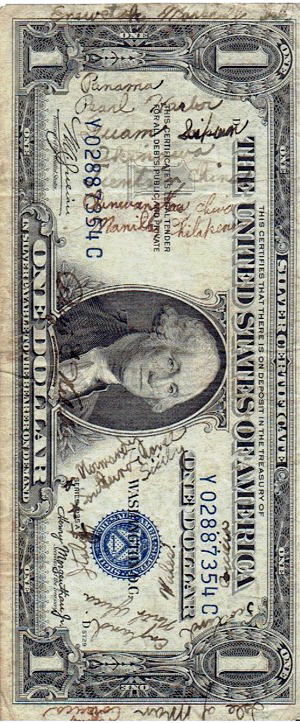

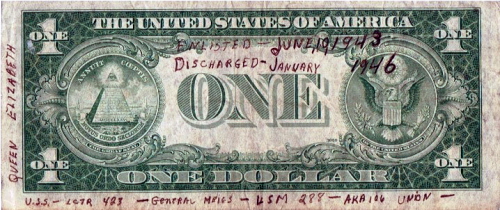

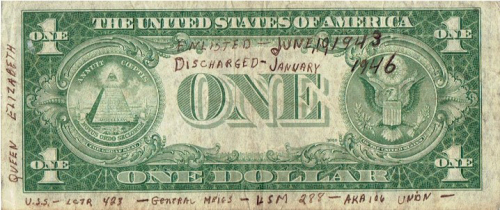

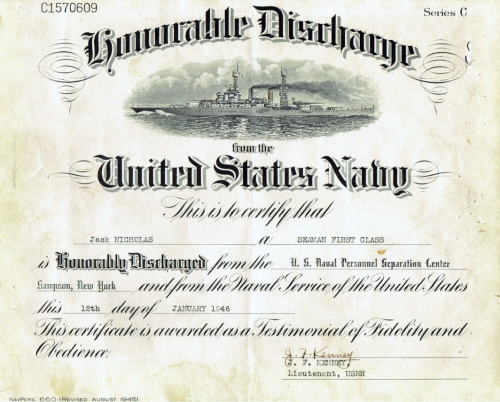

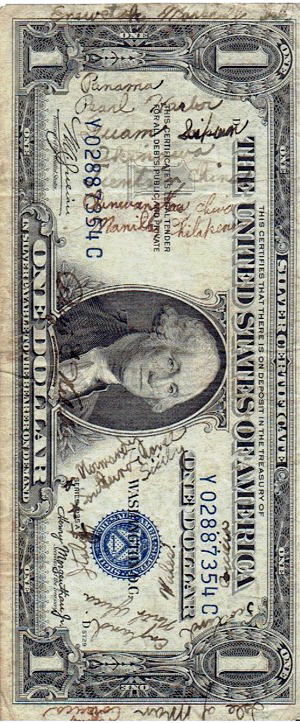

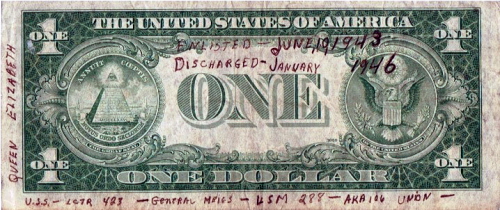

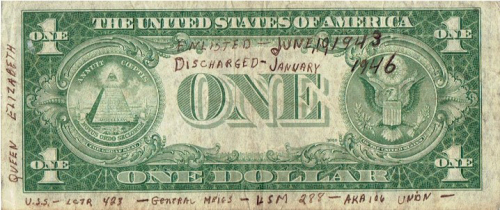

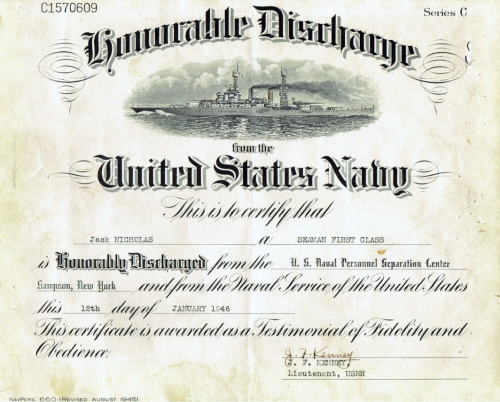

Dollar Bill with Locations and Ships

1935

US Silver Certificate Dollar Bill

Enlisted – June 10, 1943.Discharged – January 1946.

Ships:

Queen Elizabeth, USS

LCTR 423, USS

General Meigs & USM

288 (AKA

106 UNION).

Places visited:

Enewetok, Marshall Islands,

Panama,

Pearl Harbor, Guam,

Saipan,

Okinawa,

Trenton(?) China,

Okinwanstou(?) China,

Manila Philippians,

Normandy,

Southern France,

Sicily,

Italy,

England,

North Africa,

Scotland, Isle

of Man and Corsica.

|

_small2.jpg)

Late in May

Late in May

.jpg) All

craft

All

craft

The craft on Blue Beach reported

no opposition. Lieutenant J C Cohen USNR

The craft on Blue Beach reported

no opposition. Lieutenant J C Cohen USNR

%20483%20Crew_small.jpg)

%20483%20II_small.jpg)

Jack

Nicholas S 2/C,

A.T.B. Camp Bradford N.O.B, Unit

King Tent 67,

Norfolk, VA

Jack

Nicholas S 2/C,

A.T.B. Camp Bradford N.O.B, Unit

King Tent 67,

Norfolk, VA April 29.

Arrived in Dartmouth, England. It is sure pretty good weather here, but liberty

is sure lousy.

April 29.

Arrived in Dartmouth, England. It is sure pretty good weather here, but liberty

is sure lousy. June

1.

Changed rockets around today. We still didn’t go out. Still waiting for the big

push and sick of this shit barge.

June

1.

Changed rockets around today. We still didn’t go out. Still waiting for the big

push and sick of this shit barge. June

16. We

got here in Dartmouth at 02:30. We anchored out until daylight and then we came

in, went ashore and got a haircut, shower and went to the movies.

June

16. We

got here in Dartmouth at 02:30. We anchored out until daylight and then we came

in, went ashore and got a haircut, shower and went to the movies. June

26.

Didn’t go out, took rockets below deck out of the racks. Took fuses away and

then started to scrape. Went on liberty.

June

26.

Didn’t go out, took rockets below deck out of the racks. Took fuses away and

then started to scrape. Went on liberty. July

20. We

ran out of fuel and are being towed by a tug. We went through the Strait of Gibraltar

this afternoon at 1200. Gibraltar was on our left and Spanish Morocco, North

Africa on our right, the water here in the Mediterranean is dark green, where it is sort

of dark blue in the Atlantic. We are still sailing, expect to be there late

tomorrow.

July

20. We

ran out of fuel and are being towed by a tug. We went through the Strait of Gibraltar

this afternoon at 1200. Gibraltar was on our left and Spanish Morocco, North

Africa on our right, the water here in the Mediterranean is dark green, where it is sort

of dark blue in the Atlantic. We are still sailing, expect to be there late

tomorrow. July

27. It

has been very calm weather today, everything is with us, wind, swells and

current. We ought to be in Bizerta by Sat. I hope. If I don’t soon get a haircut

I’ll need a violin.

July

27. It

has been very calm weather today, everything is with us, wind, swells and

current. We ought to be in Bizerta by Sat. I hope. If I don’t soon get a haircut

I’ll need a violin. August 10. Alls

well sailing north west. Tied up on Madolelenid(?) Island at 21:00.

August 10. Alls

well sailing north west. Tied up on Madolelenid(?) Island at 21:00. October 23. Stop

again in Oran for more passengers.

October 23. Stop

again in Oran for more passengers.