|

50 (Middle East) Commando - East Mediterranean

An Integral Part of 'Layforce'

Background

In 1940, there

were proposals to set up a Commando force in the Middle East from serving

soldiers already in the theatre of operations. Early plans to raise 3

Indian Commandos and one from the Polish forces did not materialise.

However, two Commando units were raised from within British forces and a

third from Palestinian sources officered by the British, including British

Non Commissioned Officers (NCOs). This account is about one of the 2

British Commandos which became known as No 50 (Middle East) Commandos. The

other was 52 (Middle East) Commando. They later became part of a larger

Commando force named "Layforce" after its commanding officer Robert

Laycock. It drew on 'A' Troop from

No. 3 Commando,

No. 7,

No. 8 (Guards) Commando and

No. 11 (Scottish) Commando.

[Photo; Knuckle-duster knife

produced during 1940-41 for use by members of 50, 51 and 52 Commandos.

These three Commandos were raised in the Middle East and the knives were

made locally in Egypt. The hilt of the knife takes the form of a

substantial brass knuckleduster, on to which the single-edged blade is

brazed. It seems likely that more were produced than were strictly

required by the three Commando units, as numerous examples survive.

Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. © IWM (WEA 659)].

Major George

Young of the Royal Engineers, was tasked to raise the 2 British Commandos.

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, he, along with several other

officers, was posted to Egypt to plan, train and undertake, if required,

operations which would disrupt and hamper the prospective enemy. One such

operation was the destruction of oilfields in Rumania, plans for which had

been drawn up as early as the summer of 1939 because of their strategic

importance to enemy forces. Young visited the site and made contact with a

group of British engineers working there.

Back in Egypt,

a Field Company was selected from the Royal Engineers to train for this

task. Preparations moved briskly and in May 1940 they were posted to

Chanak in Turkey, which was much closer to their intended targets. Dressed

in civilian clothes, the men worked on improvements to local roads and the

harbour. However, by the spring of 1940 and the evacuation of the Allied

expeditionary force from Dunkirk, the Royal Engineers returned to Egypt

due to sensitivity over Turkey’s neutrality and Rumania’s leaning towards

Germany and her Axis allies.

Young was now

put in charge of raising the Middle East Commando assisted by an officer

from the Durham Light Infantry, Captain Harry Fox-Davies.

No 50 Commando

-

Recruitment

By July 1940,

No 50 Middle East Commando had a provisional strength of 371 all ranks. It

comprised an HQ and 3 Troops, each of 4 Sections, under the command of a

Section Officer with 25 other ranks under his command. A Royal Army

Medical Corps (RAMC) doctor and 3 orderlies were attached together with a

Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) sergeant and 2 interpreters they could

call upon as required.

With HQ

restrictions on the redeployment of tank crews, engineers and men from the

technical arm of their forces, all ranks were recruited from the infantry,

with a maximum of 10 all ranks from any single Battalion or Regiment.

However, some men were recruited from the 1st Cavalry Division, then in

Palestine. They were mainly from Yeomanry Regiments still using horses,

although conversion to armour would soon follow. To these were added a

number of Spaniards who left Spain after the Republican Forces were

defeated by Franco’s army during the Civil War.

They originally

crossed the Pyrenees into France with the intent of enlisting in the

French Army to carry on the fight against the Fascists. Most were sent to

Syria, then a French mandate, while others found themselves in the French

Foreign Legion. With the fall of France and the creation of the Vichy

Government, Syria fell into line with Vichy and again fearing that their

safety, the Spaniards commandeered a couple of vehicles and crossed the

border into Palestine, where they declared their intent to fight under the

control of the British. The 63 men were interviewed by Young and

Fox-Davies in Moascar. The Spaniards were regarded as a valuable asset and

were accepted into the ranks of the Commandos.

Training

By August 1940,

the Commandos were based at Geneifa in Egypt and training had begun. Where

possible, sections comprised men from the same Regiment. Their primary

task was to mount raiding operations on enemy coastlines which, with Italy

now fighting on the side of the Axis powers, would likely include the

Libyan coast as a prime target.

The men were

all trained soldiers, but for the challenging tasks ahead, more rigorous

training was required in endurance and physical fitness. Each man was

expected to undertake three 30 mile marches, in full kit, within the space

of 24 hours on consecutive days! The use of water and consumption of food

were strictly controlled. Military discipline would be invoked if

permission from an Officer or NCO was not obtained in advance. Such

rigorous controls were necessary because of the arid terrain, extremely

high day-time temperatures and remoteness from support and supplies. It

was envisaged that most work would be undertaken during the hours of

darkness, with the hottest parts of the day, laid up, under shade.

They had to be

self-sufficient with each man carrying enough food and water for the

duration of each operation. They unsuccessfully experimented with dried

beef but settled on the ubiquitous Bully Beef with packs of rice, dates,

limes, army biscuits, chewing gum, tea and sugar. A full bottle of water,

along with a water purification kit, allowed them to replenish their

bottles if they came upon a water source.

Just

before Italy’s declaration of war in June 1940, Lt. General Maitland

Wilson, known to many as Jumbo, explored the feasibility of raising a unit

of paratroops to operate behind enemy lines, but with parachutes in short

supply in this theatre of war, the idea was shelved. Landing craft for

training exercises were similarly scarce, so they made do with a few old

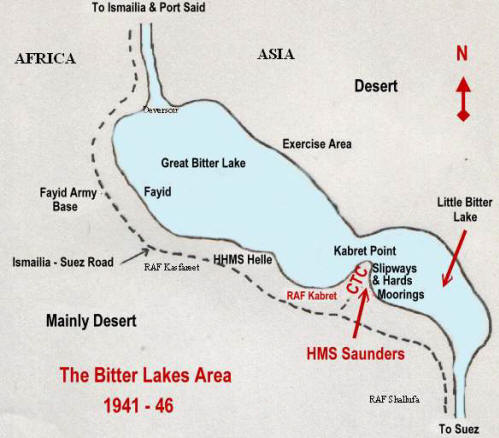

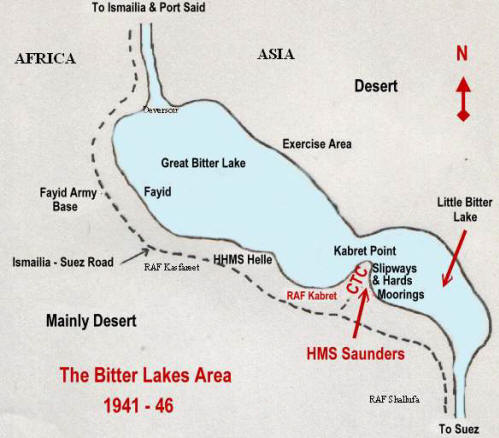

whalers and rafts that they could improvise. They commenced the nautical

part of their training at the

Middle East Combined Training

Centre

on the Bitter Lakes, which formed part of the Suez Canal. Just

before Italy’s declaration of war in June 1940, Lt. General Maitland

Wilson, known to many as Jumbo, explored the feasibility of raising a unit

of paratroops to operate behind enemy lines, but with parachutes in short

supply in this theatre of war, the idea was shelved. Landing craft for

training exercises were similarly scarce, so they made do with a few old

whalers and rafts that they could improvise. They commenced the nautical

part of their training at the

Middle East Combined Training

Centre

on the Bitter Lakes, which formed part of the Suez Canal.

[Maps of the training area opposite and

below].

All Private

soldiers now assumed the new rank of Raider and uniforms were adapted for

rough service. Hard rubber soles were added to regular issue boots and

regular issue shorts gave way to khaki drill trousers. The wardrobe

changes included a bush type jacket and a hat similar to that worn by

Australian forces, although some opted for the old pith helmet.

The weapon for

other ranks was the standard issue .303 SMLE rifle with Bren gun teams,

NCOs and Officers carrying revolvers. Thompson sub-machine guns were

issued to NCOs. The Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife, not yet in general

service with the Commandos, was a fearsome weapon with a knuckle duster on

the handle. This became the unofficial badge for the Middle East Commandos

and was known as a Fanny.

All Commandos

received training in the use of explosives for demolition work, an

essential part of many clandestine operations behind enemy lines. Not all

were proficient, at least in the early period, because of constraints on

time and supplies of explosives but the objective was for all to be able

to set simple charges on land and underwater.

In

October 1940, Young was promoted Lt. Colonel and Fox-Davies stepped up to

Major becoming 2nd in command. Training was still going on apace until all

had fully completed the Commando training course. Back at MEHQ, plans to

expand the Commandos continued with the previously 3 Indian Commandos

further augmented by a 4th British Commando; but once again, these plans

did not come to fruition. In

October 1940, Young was promoted Lt. Colonel and Fox-Davies stepped up to

Major becoming 2nd in command. Training was still going on apace until all

had fully completed the Commando training course. Back at MEHQ, plans to

expand the Commandos continued with the previously 3 Indian Commandos

further augmented by a 4th British Commando; but once again, these plans

did not come to fruition.

Early Deployments

After the

Italians crossed the border into Egypt on the 13th September 1940, the

Commandos were deployed, even although only part of No 50 was operational.

In mid-October, they were ordered to attack Bomba to the east of Benghazi

on the north African coast, a recently established Italian seaplane base.

It had been already been attacked by aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm during

August but the objective now for No 50 Commando was the destruction of the

base.

At Geneifa on

the Suez Canal, Young and Fox-Davies planned the operation with both

Captains of their escorting ships, the destroyers HMS Decoy and HMS

Hereward. With the aid of air photography, maps and a mock-up of the

target, they finalised their plans and several rehearsals were carried out

to familiarise each man with his particular tasks. They were to land at

00.00 hours, guided in by an RN submarine and then to attack the tents and

huts of the Italian garrison. Meanwhile, Royal Navy motor launches would

attempt to destroy the moored, Italian seaplanes, using rockets.

On

the night of the 28/29th October, in great secrecy, the Commandos boarded

their escort destroyers moored in the Great Bitter Lake and set off for

Port Said. For security reasons, they were confined below deck, out of the

sight of any prying eyes. Just when the weeks of planning and rehearsals

were about to pay off, the operation was cancelled when the Italians

declared war on Greece. On

the night of the 28/29th October, in great secrecy, the Commandos boarded

their escort destroyers moored in the Great Bitter Lake and set off for

Port Said. For security reasons, they were confined below deck, out of the

sight of any prying eyes. Just when the weeks of planning and rehearsals

were about to pay off, the operation was cancelled when the Italians

declared war on Greece.

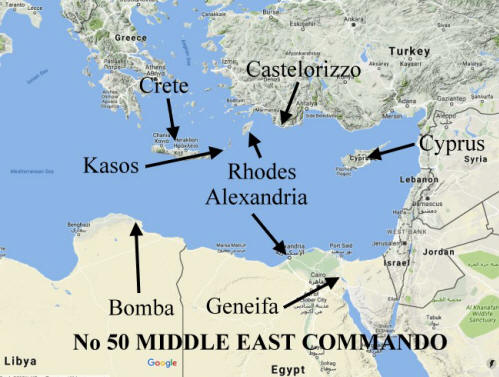

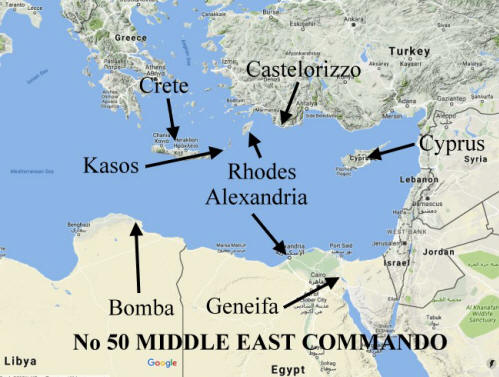

[Map of Eastern Mediterranean courtesy of

Google Map Data 2017].

The raiding

force was recalled to Alexandria over concerns that both Greece and Crete

would be invaded, the latter occupying a strategically important position

in that area of the Mediterranean.

Many of the

Commandos were bitterly disappointed by this turn of events after so much

planning and training. However, unbeknown to anyone at the time, this was

only the start of a period of cancelled Layforce operations. On the night

of 16/17th January 1941, the Commandos embarked on a raid of the

Dodecanese island of Kasos (Operation Blunt), but this was cancelled just

as landing vessels were being lowered into the water and a second attempt

on 17/18th February was also aborted.

Admiral of the

Fleet, Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean, had his

sights on the island of Castelorizzo, about eighty miles east of Rhodes

and just three miles off the Turkish coast. He wanted a secure motor

torpedo boat base to support future operations against the Italians in the

Dodecanese.

At

Geneifa on the Suez Canal, Young and Fox-Davies planned the operation with

both Captains of their escorting ships, the destroyers HMSs Decoy

and Hereward. With the aid of air photography, maps and a mock up

of the target, they finalised their plans and several rehearsals were

carried out to familiarise each man with his particular task. They were to

land at 00.00 hours, guided in by a RN submarine and then to attack the

tents and huts of the Italian garrison. Meanwhile, Royal Navy motor

launches would attempt to destroy the moored, Italian sea planes, using

rockets.

On the night of the 28/29th

October, in great secrecy, the Commandos boarded their escort destroyers

moored in the Great Bitter Lake and set off for Port Said. For security

reasons they were confined below deck, out of the sight of any prying

eyes. Just when the weeks of planning and rehearsals was about to pay off,

the operation was cancelled when the Italians declared war on Greece. The

raiding force was recalled to Alexandria over concerns that both Greece

and Crete would be invaded, the latter occupying a strategically important

position in that area of the Mediterranean.

Many of the

Commandos were bitterly disappointed by this turn of events after so much

planning and training. However, unbeknown to anyone at the time, this was

only the start of a period of cancelled Layforce operations. On

the night of 16/17th January 1941, the Commandos embarked on a

raid of the Dodecanese island of Kasos (Operation Blunt), but this was

cancelled just as landing vessels were being lowered into the water and a

second attempt on 17/18th February was also aborted.

Admiral of

the Fleet, Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean, had

his sights on the island of Castelorizzo, about eighty miles east of

Rhodes and just three miles off the Turkish coast. He wanted a secure

motor torpedo boat base to support future operations against the Italians

in the Dodecanese.

Operation Abstention - "Confused,

Incompetent, Inept and a Mess"

On

the evening of the 23rd/24th February 1941, 200 men set off for

Castelorizzo aboard HMS Decoy and HMS Hereward, accompanied by escorts

including an Australian cruiser. Operation Abstention was underway. Each

of the destroyers carried 5 whalers to carry the men, their supplies and

ammunition ashore. These craft were not as versatile as landing craft, so

supplies were broken down into easy to man-handle loads. The gunboat, HMS

Ladybird, carried 24 Royal Marines and two agents from the Special

Operations Executive (SOE) were embedded within the British forces. On

the evening of the 23rd/24th February 1941, 200 men set off for

Castelorizzo aboard HMS Decoy and HMS Hereward, accompanied by escorts

including an Australian cruiser. Operation Abstention was underway. Each

of the destroyers carried 5 whalers to carry the men, their supplies and

ammunition ashore. These craft were not as versatile as landing craft, so

supplies were broken down into easy to man-handle loads. The gunboat, HMS

Ladybird, carried 24 Royal Marines and two agents from the Special

Operations Executive (SOE) were embedded within the British forces.

[IWM 1941 photo

of an RN whaler. © IWM (A 6079)].

However,

there was a major flaw in the planning of the operation - the Commandos

had not been involved. This was a major error clearly demonstrating

that some officers did not understand the vital need for joint planning in

Combined Operations. It was the only way to achieve the high level of

commitment, cooperation, communications, coordination and mutual

confidence needed to achieve success.

Issues the

Commandos might have raised, had they been consulted, included; 1) their

dual role as an amphibious assault/invading force and an occupying force

with defensive responsibilities for which they were not trained, 2) the

type of craft to transport them and their supplies from their mother ship

to the shore were not suitable for the task and too few in number, 3)

their planned billets required them to march in full view of potential

spies and sympathisers who could report numbers, disposition, armaments

etc to the enemy on neighbouring islands.

Despite their

concerns about their lack of involvement in the planning process, the

Commandos struck up a good rapport with their Royal Navy counterparts on

the destroyers. They took an indirect course to the island, heading

initially for the Palestinian coast before steaming on to Categorize. The

short voyage took less than a day and aimed to reach the island by 03.00

hours on the 25th where a Royal Naval submarine would guide them into

their final position south-west of the island.

As

darkness fell, the Commandos emerged from below decks, made their final

preparations and proceeded to board the navy’s whalers. One of the landing

parties rowed into the harbour alerting the Italian garrison and causing

another boat to return to its mother ship. However, those in the harbour

swiftly dealt with the opposition and consolidated their position. The

remainder of the force landed successfully and prepared for the arrival of

the garrisoning force.

Before

daybreak, the naval forces of the 3rd Cruiser Squadron withdrew, leaving

only the Ladybird in support. She, at first light, shelled one of the

Commando's objectives, the Palecastro Fort, to which the Italian garrison

had withdrawn and one company of Commandos attacked the town itself,

overcame the sentries and took control. The Italian garrison put up very

little resistance.

A

2nd company of Commandos, assisted by gunfire from the Ladybird, began

their assault on the fort whilst the remainder scaled the heights at the

flanks of the fort to cut off any attempted escape. The Italians,

uncharacteristically, resisted strongly but, by 10.00 hours, the fort was

finally under Commando control. Although Italian communications had been

destroyed early in the landing, they had alerted their compatriots on

other islands of their predicament. A

2nd company of Commandos, assisted by gunfire from the Ladybird, began

their assault on the fort whilst the remainder scaled the heights at the

flanks of the fort to cut off any attempted escape. The Italians,

uncharacteristically, resisted strongly but, by 10.00 hours, the fort was

finally under Commando control. Although Italian communications had been

destroyed early in the landing, they had alerted their compatriots on

other islands of their predicament.

The Italians

responded with unexpected vigour by shelling and bombing the small British

invading force. The British plans to land a company of the Sherwood

Foresters to form a garrison began to unravel as the Italian air and naval

activity made further landings impractical, forcing them to return to

their base in Cyprus, with the intention to return at a later date.

Meanwhile, the

Italians forced a landing on several beaches of Castelorizzo putting the

Commandos under pressure. Air attacks damaged HMS Ladybird which was

running short on fuel forcing them to return to Cyprus with her small

contingent of Royal Marines. This compounded the Commandos difficulties as

the Ladybird was their only radio link with the outside world. Throughout

the day, the Italian air force bombed and strafed the Commando positions,

killing 3 and wounding 7. Dusk brought a welcome respite... but not for

long. An Italian warship entered the harbour, lit up the Commandos

defensive positions with a searchlight and shelled the area forcing them

to withdraw. Although limited in weaponry, the Commandos shot down 2 enemy

bombers and forced a third into the sea. The crew were rescued by

islanders.

The Italians

followed up this initial bombardment by landing around 240 soldiers just

north of the harbour while their warships shelled the British positions.

The British navy intended to disrupt the Italian forces but were unable to

make contact with them. Rough seas provided a day of respite from naval

bombardment but the Commandos position was bad and likely to worsen. They

were isolated from supplies and reinforcements with no means of

communication and the plan envisaged they would be relieved within 24

hours of landing. They were provisioned accordingly. Food and drink could

be obtained locally but their ammunition was inadequate for a sustained

action.

Around this

time, the Small Fleets commander was replaced by Captain Egerton of HMS

Bonaventure due to illness.

When the

weather improved, the Italians resumed their troop landings, shelling and

air force sorties, increasing the pressure on the Commandos but causing no

serious casualties. In their turn, the Commandos unsuccessfully tried to

make contact with the Royal Navy by torch signals, but when their

batteries ran down they were left with matches as a light source. The

outlook was bleak and some no doubt felt abandoned with death or being

taken prisoner realistic prospects. The positions they held were well

spread out but they still managed to send out patrols to the beaches while

working parties went in search of Italian rations. The possibility of a

counter-attack was considered but not followed up due to time constraints.

With the

landing of more enemy troops from 2 destroyers in the harbour, the gravity

of the Commando's situation worsened when the Italians infiltrated the

Commando positions close to the cemetery. By midday the Commandos, which

had been split into 2 groups, one still covering their landing beach and

the other covering the cemetery, the town having been given up earlier,

had to withdraw to the high ground to avoid being overlooked by the enemy.

This pre-emptive redeployment proved fortuitous as the Italians landed

more troops on the Commando's landing beach while under covered by one of

their destroyers. As dusk fell, the Italians occupied a ridge some

three-quarters of a mile from the consolidated British positions and began

to advance towards them in sections. At around 300 yards they opened fire

with rifles and Bren guns. Nightfall brought this little action to a halt.

By this time

the Commandos had run out of food and water and all sources of water were

held by the Italians. With their reserve ammunition on a beach occupied by

the enemy, their ammunition was down to what the men carried in their

pouches. Their force was depleted by around 60 officers and men who were

missing from the main party. Morale was on the wane since there were no

sensible options open to them. It was only a matter of time when further

resistance would be futile. The 4th day was punctuated by ineffective

naval shell fire and bombs and their desperate situation seemed quite

hopeless when British destroyers from the relieving fleet, returned to the

island and made contact.

Aboard one of

the destroyers were men of the Sherwood’s, known affectionately as the

Notts and Jocks. When they landed the witnessed the results of the 4-day

action and found at least one dead Commando. However, they also made

contact with some of the men cut off from the main force of Commandos.

They occupied an isolated small plateau on the east of the island and

since their position was untenable, and with the failure of the garrison

to arrive from Cyprus, their only option was to withdraw.

Although most

men were able to re-embark some were left behind and became prisoners of

war. As the re-embarking men passed by the old Venetian fort on the way to

the dock, one of the SOE operatives called the operation ‘confused,

incompetent, inept and a mess’. The soldiers, carrying their weapons and

equipment, awaited evacuation and must have reflected on the total

breakdown of communications. The debacle brought scathing comments from

Admiral Cunningham who described the operation as ‘A rotten business and

reflected little credit to everyone’. During the 4 days of fighting, No 50

Middle East Commando lost 32 men either killed, wounded, prisoners of war

or missing. 50 ME Commando departed Castelorizzo in March for Crete being

replaced in their garrison duties there by the 1st Royal Welch Regiment.

They returned to Geneifa on the Suez Canal where they were amalgamated

with their comrades from No. 52 Middle East Commando.

On the Athens

Memorial in Greece are the names of Tom Blackburn, Jack Pollard, James

Bate, Francis Tunstall, John McCormick, Leslie England, George Robinson

and Richard Sharman. These men were from the group who were cut off and

unable to re-embark with the main body of Commandos. They, along with

others, attempted to escape by swimming across the water to nearby Turkey

but were unable to make it. Their bodies were never recovered. There is an

account, held at the Imperial War Museum, of three commands who

successfully completed the swim. Also named on the memorial was 2nd

Lieutenant Michael Arnold Smith of the Royal Sussex Regiment. He was

killed on the beach during an air raid. Sadly, his body was never

recovered. On the island of Rhodes lie the graves of the 3 other ranks who

were killed in the action, Harry Knott, Alfred Taylor and Ernest Dawes.

Troops on

Special Service returned to this island 3 years later when the Special

Boat Service filled the space the Italians left behind when they

surrendered in September 1943. They used the island as a base for

operations against the enemy, rekindling the spirit of its original

planned use.

Before these ideas were executed, an entirely different deployment came to

the fore on the 28th November 1941 when both No 51(Jewish) and No 52

Middle East Commandos were put on 24hours notice to move. The planners of

General Wavell’s limited offensive 'Operation Compass', to attack Italian

forces in western Egypt and Cyrenaica, the eastern province of Libya, saw

a role for them to play but they were stood down on the 1st December 1941.

Further Reading

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Associated Link of Possible Interest;

52 (Middle East) Commando

Acknowledgements

Researched and

written by Alan Orton. Redrafted for website presentation by Geoff Slee

and approved by the author before publication.

|