|

516 Squadron RAF

(Combined Operations) -

A Pilot's Story

Lighter Moments in the Life

of a Pilot at RAF Dundonald, Ayrshire, Scotland

New Zealander, Douglas Shears, served with 516 Combined Operations Squadron

at RAF Dundonald in Ayrshire, Scotland from 17/7/44 to late December 44.

The light hearted anecdotes which follow were part of an exchange of letters between

Doug in New Zealand and Phillip C Jones in the UK during the mid 90s, when Phil

was researching the squadron. Doug's Commanding Officer (CO) was Squadron Leader I G MacLaren, DFC. New Zealander, Douglas Shears, served with 516 Combined Operations Squadron

at RAF Dundonald in Ayrshire, Scotland from 17/7/44 to late December 44.

The light hearted anecdotes which follow were part of an exchange of letters between

Doug in New Zealand and Phillip C Jones in the UK during the mid 90s, when Phil

was researching the squadron. Doug's Commanding Officer (CO) was Squadron Leader I G MacLaren, DFC.

[Photo; Doug Shears, RNZAF,

1945].

Posting to Dundonald

My transfer to 516 Combined Operations Squadron

had more to do with gaining a

commission than the operational needs of the Allied cause! I had been at the Coastal Command Station at St Eval, near Newquay,

Cornwall, since September 1943. A few weeks before

D-Day I was interviewed by the Group Captain for a

commission. There were three applicants; an

Englishman, a Canadian and myself. At that time I

was 21 years of age. His questions turned to my university education. I had none

since I joined the RNZAF in 1940, when I was just 18 years of

age. Despite these mitigating circumstances, the Group Captain held firmly to his belief that all RAF

Officers should have a degree. It was no surprise that the successful candidate was a former naval architect with a university degree!

The Orderly Sergeant at St Eval

suggested I should write to the Air Commodore in command of the RNZAF in Britain

to apply for time off to attend University. About 10 days later I met him in his

London office when he

suggested that I put my future in his hands, to which I readily agreed. His plan

was to post me to another unit within 6 months when I'd be recommended

for a commission by another Commanding Officer. In the event that this did not happen, he would grant me a commission himself.

In a matter of weeks I was posted to Dundonald and after 6 months I reported to the Group Captain at Prestwick about

my wish to gain a commission. Word soon spread and the general feedback was that my chances of success were zero. I was told that the Group Captain

"is too tough

and doesn't give out commissions unless he knows the applicant personally". When I marched into the "great man's" presence, he kept me

standing at attention for a while and then told me to drag up a chair and sit down. He asked a few

work related questions but we mostly talked about New

Zealand. He too had served with our RNZAF Commodore in the same Bomber Squadron and was very pleased to recommend me for a commission!

I have many

fond memories of my time at RAF Dundonald and some of these are reproduced

below.

Photographic Mission Photographic Mission

There was an aerial photographic department at Dundonald.

Once a month a planned series of overlapping aerial photographs

were taken of selected places from an altitude of 10,000 ft. It was a cold February morning when I took off in an Anson on my first photographic mission over the Prestwick area.

I was

accompanied by Flight Sergeant Millard as photographer. The camera was mounted under the nose of the aircraft with the hatch removed. This had the

effect of reducing

the temperature inside the aircraft to below freezing at the operating height. Near the completion of the last run, we drifted out of range, which

necessitated another run over Prestwick. This we did but, much to our annoyance, we once more drifted off target near the end of the run.

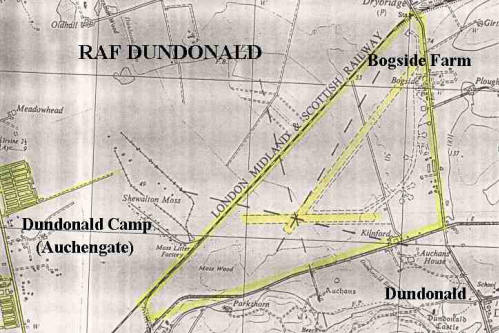

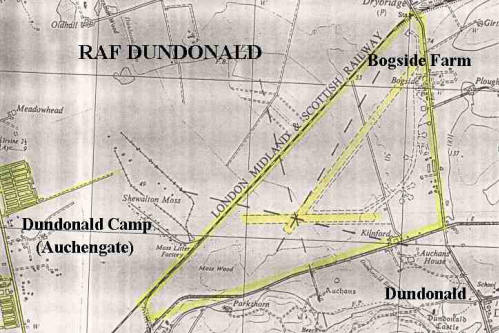

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

By this time we were frozen to the marrow so we decided to return to base. We didn't want to admit our failure, so

I suggested that we should report that the area was clouded over and that photography had been impossible. When we landed, we discovered that we

had been transmitting our conversations without a break for more than an hour!... I had inadvertently switched on the transmitter with my elbow.

Our cover story was well and truly blown but there were worse ramifications to follow... much worse. While we had been on the air, 8 Hurricanes were on exercise over Loch Fyne

using the same radio frequency. Their exercise had to be aborted because we were blocking the frequency!

Embarrassingly for us, we had been singing and telling stories, some a bit risqué. We landed at Dundonald just ahead

of the Hurricanes returning from Loch Fyne. I couldn't imagine a worse situation to be in but there was more bad news - the CO was leading them!

My instinct was to hide but since there was nowhere to go, I stood in front of the control tower to await my fate. Fortunately the CO had a great sense of fun and enjoyed a good story. As he approached he said "What a

performance you two put on! Many of the stories were new to me but for God's sake next time turn off your transmitter! You ruined our operation

and it's lucky that the Air Ministry bods weren't listening in. By the way

you'll have to do it all again if your mission was not successful". We kept our

fingers crossed and all was well in the end.

John Bone

John was, I believe, an Oxford Graduate

with parents who were well

known pillars of society. I was most impressed with his English attitude to life down to

his favourite tipple of whisky and soda. His flying skills in Hurricanes were

exceptional, which could not be said of his ability to organise a large party!

John occupies a special place in the

collective memory of those who were at Dundonald when 516 Squadron was gradually

being run down towards the end of 1944. The CO suggested a big farewell party for

departing officers, other

ranks and airmen should be organised and John was put in charge of the

arrangements.

To obtain an estimate of

the amount of beer to order, he asked me how

much one person might drink in a night. I suggested 4 or 5 pints should be ample. He thanked me and carried on. He

consulted a couple of passing airman, who thought a gallon for each person

attending the party would suffice.

Happy with his research, he threw

caution to the wind and ordered 200 gallons for the estimated 200 attending.

Unfortunately, in all his careful calculations, John had not anticipated that

about half the personnel would be posted to other commands before the day of the

party! Needless to say, those who did attend had a great time with no limit on

the beer we could drink. Next morning an unknown amount of beer was returned to

the brewery, but not as much as anyone might think!

The

Squadron Moggie

There was a cat called 'Tito' at Dundonald. He was a 'moocher par excellence' and an accomplished mouse catcher.

Each Friday morning, while breakfast was being served, he would

strategically place half a dozen dead mice in the middle of the main exit such

that nobody could fail to notice them. With what looked like a

self-satisfied smirk on his face, he accepted the congratulations of his captive audience

as they left the mess but was particularly grateful to those who gave him a

small portion of their Friday chocolate ration. How he knew to put on this performance on chocolate ration

Friday, we'll never know but his unique talent had not gone unnoticed by the person who named him. His namesake, Marshall Tito of Yugoslavia, was a great organiser,

who made the most

of opportunities while he had the chance!

Occupational Hazards

The main training beaches

for simulated landings on Loch Fyne were around 50 miles north of Dundonald. In

the later stages of combined army and navy training, the Air Force provided

realistic battle conditions and

swivel and sighting practice for anti aircraft gunners etc. To achieve realistic attacks

on landing craft, very fast low-level passes stretched the safety envelope to the

limit.

Bob (Vivian) Thomas was flying a Blenheim in a group of 2 Blenheims

and 3 Hurricanes, when his attention was distracted by a warning over his R/T

(radio transmitter) just as he was making a very low level 'attack' on a landing

craft. In the time it took to

check for nearby aircraft, he found himself on a collision course with the

landing craft's mast. The underside of his plane was ripped open, the bombing doors and rear landing wheel

were lost and the

main structural spar was fractured. As he returned to Dundonald, he reported his position

and circumstances on several occasions. I was acting controller when Bob appeared on the

landing circuit and saw bits falling off the

aircraft as it passed overhead. He landed

safely, but, on examining his plane, it was declared a write-off since Blenheims

were no longer in operational use.

Visitor from

America! Visitor from

America!

The

21st of October 1944 was a quiet day with little air traffic between Dundonald and Loch Fyne. I was in the

process of reporting the day's work to the CO when a very low flying B17g

bomber appeared at the downwind end of our runway. To our consternation it appeared to be attempting a landing on our very short

'Somerfelt' landing strip!

I fired a red

Verey signal into the sky - a 'last resort' warning to the crew not to land; but the American pilots ignored it. I tried to fire another one but it was a dud and, by this time, the plane had landed.

They had flown in from Newfoundland and in poor visibility the crew had mistaken Dundonald for Prestwick.

Take off from our

relatively short runways was not a sensible option and I believe the aircraft

was dismantled and transported by road to nearby Prestwick.

Bird Strike!

While I was waiting to return to New Zealand after three years service in the

UK, I stayed on at Dundonald, while it was in the process of running down. It fell to me to fly our three Blenheims back to the Filton factory near

Bristol. The planes were stripped of everything except essential equipment and instruments leaving me with a turn and bank indicator, a compass

and not much more. At the start of the first trip I decided to buzz the Sergeants' Mess, so I climbed up to about 3000ft and approached the building at about 275mph in a shallow dive. I

was just about to roar over the roof when a large seagull knocked out the front perspex

panel, which disappeared in a splatter of blood and

feathers. It was like hitting a brick wall! The

punishment for my little bit of bravado was to fly

the 400 miles to Bristol with a blast of cold air

blowing through the fuselage. It was more than

just uncomfortable and I nearly succumbed to the

extreme cold.

With my pilot's parachute over my shoulder and my haversack on my back I made the return trip to Dundonald

via London, Glasgow and Kilmarnock. On the second trip I ran into low cloud and,

as I was short of a radio and many instruments, I landed somewhere in Cumberland,

where I stayed the night. I was cleared for Bristol the next day and then made

the now familiar journey back to Scotland. After a day's rest I made the third

and final flight to Bristol. On return to Dundonald the CO gave me a 48 hour pass for rest and recuperation but instead I went to Glasgow to see the sights!

I Flew like a Bird!

A

spare part was needed for Tiger Moth DH 82, which

required a 160 mile round trip from Dundonald to an Elementary Flying Training

School (EFTS) field just north of Carlisle. It should have been straightforward but when the field came into view, it was clear from the

short length

of the grass strip, that it was designed for Tigers only. I throttled back on the final approach but couldn't get the speed under 100

knots when a normal landing was half that speed. I glanced out of the port side window and realised that there was a big difference between the Air

Speed Indicator (ASI) and the passing scenery! Clearly the ASI had stuck at 100

Knots and the plane was just about stalling at 25

Knots. knots when a normal landing was half that speed. I glanced out of the port side window and realised that there was a big difference between the Air

Speed Indicator (ASI) and the passing scenery! Clearly the ASI had stuck at 100

Knots and the plane was just about stalling at 25

Knots.

[Photo; Avro Anson].

However, the wonderful

old Anson did not let me down and I landed in less than half the length of the field. The CO of the EFTS

was dubious about the Anson taking off on such a short runway but I had no

doubts. After we stowed the spare part, and with the assistance of 6 airmen to hold the tail of the Anson

in a flying attitude until I had both engines at about 3/4 power, I throttled up

knowing that the Anson would almost fly like a

helicopter. She lifted off the ground about half way down the grass strip and climbed at about 30 Knots. I then gave her full flap and she

rose like a bird clearing trees along the airfield boundary by at least 100 ft. The CO and his pupils learning to fly Tigers, must have been

impressed. Little did they know that the faithful Anson was one in a million and anyone could have achieved the same spectacular performance.

The 2 Ansons based at Dundonald had been in the Fleet Arm (Navy) at one time and the airspeed was in knots not MPH. Ansons in general were the safest aircraft I

flew and this particular one stalled at 25 knots and, even then, it was so docile that it just floated gently downwards. At 26 knots it tried to

fly in a normal attitude again! Because of the lack of stalling characteristics, we flew this Anson into quite short airfields so, apart from the

faulty ASI, I had no concerns about landing at Carlisle.

Navy Exercises at Troon

We were to provide trainee Navy Ack Ack crews with simulated attacks in preparation for their posting

to the Far East. To be effective, these simulations had to be realistic and there had been some criticism from the Admiral that, in

the past, the altitude of the attacking planes had been too high and the speed too low. The CO was, not surprisingly, somewhat disgruntled at the criticism of his pilots,

so he led this

particular flight himself. He briefed his pilots to fly at high speed at an altitude of just a few feet over the

target area. This was achieved, but with tragic results. One soldier stood up and was fatally wounded by a propeller. These realistic simulated

training exercises were not war games and needed to be treated with great care and respect when live ammunition and cardboard bombs, which could kill within a range of a few yards, were used.

Dr Jack Reid

Doctor Jack Reid was the Medical Officer in charge of accidents, coughs and colds and all things related to

health matters. He also loved flying as a passenger. Whenever possible he would

accompany me on official flights around the UK. This was the case on a flight to

Hendon, London. Doc Reid ensured his orderly could handle the daily sick parade

of 6 patients with

routine conditions. We left Dundonald just after 8 am in an Anson and the flight itself was uneventful. When we returned to Dundonald at about 6 pm there

was an urgent message for Doc Reid from the CO. He received a real dressing down because one of our airmen had broken his leg while we were joy

riding over the south of England. Matters were made all the worse since the CO had to call on the services of the Navy doctor! Doc Reid's wings were clipped

since future flights he undertook had to be authorised by the CO himself! I was

to meet Doc Reid again in the 1950s when he visited us at our home in New

Zealand. He later settled in Auckland in the Eastern Bays district and I kept in touch with him for many years.

The Smoke Screen The Smoke Screen

We were scheduled to lay a smoke screen along some 'landing beaches' on Loch Fyne while mock landing exercises

were taking place. The weather conditions were unsuitable so we were stood down. Since we had loaded the 3 Blenheims with the smoke canisters, the

CO ordered us to "Put the smoke down on our field and let's see how good you are at your

job." The

first Blenheim pilot laid the smoke right on target which unfortunately included a parked double-decker bus! I was next about 5 minutes later and, as I flew

in front of the same bus, I just had time to see him shake his fist before he disappeared from view for the second time. I was just landing when

the last

Blenheim put the third and final smoke screen on the ground just as the bus was about clear of my screen. The bus driver was no doubt unimpressed

but the CO was more than satisfied with our efforts! That

evening in a Kilmarnock pub we heard someone remark that during the afternoon it suddenly and unexpectedly became overcast in the Dundonald area!

We listened attentively but maintained a discreet silence!

The Day We Shot-Up Troon!

We had 3 Blenheims and 6 Hurricanes in the air on this occasion. The target was situated in the centre of the

business area of Troon in Ayrshire. We had instructions to "shoot up" a gun emplacement which was positioned in a derelict building that had been

burnt out some years before. The engagement had to be fast and furious and we attacked them

from all sides. They were out-gunned and had it been a real attack, they would have been wiped out. It must have been an unusual sight

for the local population to witness so

many planes targeting the middle of their town!

In these operating

conditions it was vital to keep a good watch on what was happening around you.

To reduce the risk of collision, all the planes turned the same way. Later that

day our CO received a signal from the Admiral congratulating the

RAF on a fine example of low flying, surprise attack, which was just what his men needed.

The 3 Blenheims were fitted with sirens which created the noise of real battle

conditions. On the ground pandemonium prevailed, which was ideal training for men

who were shortly to be posted to the far east.

Postscript Postscript

Doug had seen service with 428 RCAF Squadron flying Wellington bombers on operational duties and at RAF St Eval

prior to joining 516 Squadron. His tour of duty was close to four years, at the end of which he was just 22 years old.

[Photo; the Author circa 2000].

On return to New

Zealand after the war, along with some colleagues, he started a company called Helicopters (NZ) Limited. He took advantage of an opportunity to learn to

fly helicopters in America and became the first Kiwi to fly commercially in the USA in 1955. In June 1960, he was appointed a companion of the Royal

Aeronautical Society.

Further Reading

There are around 300 books

listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be purchased on-line

from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE), whose search banner checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and paste the title of your

choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's no obligation to

buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

516 Squadron on this website

Airfield Focus - No. 35 Dundonald by Phil Jones. Published by GMS Enterprises, 67 Pyhill, Peterborough,

PE3 8QQ in 1998. 34 Pages. ISBN1 870384 66 0 £4.95.

Damn my Two Left Feet....and how I Flew with Them by Doug Shears. Published 2001 by Jeff Mill &

Associates 4/8 Nile Street, Timaru, New Zealand.

Acknowledgments

These are the memories of New Zealand pilot, Douglas

Shears They are based on an exchange of letters between Doug and Phillip C

Jones in the mid 90s and we're grateful to both for allowing us to use the

material.

|

knots when a normal landing was half that speed. I glanced out of the port side window and realised that there was a big difference between the Air

Speed Indicator (ASI) and the passing scenery! Clearly the ASI had stuck at 100

Knots and the plane was just about stalling at 25

Knots.

knots when a normal landing was half that speed. I glanced out of the port side window and realised that there was a big difference between the Air

Speed Indicator (ASI) and the passing scenery! Clearly the ASI had stuck at 100

Knots and the plane was just about stalling at 25

Knots.