|

524 LCA Flotilla on D DAY.

Ferrying soldiers from troop ships to Gold beach

under heavy fire

Background

524 LCA

Flotilla comprised 18 craft, 15 of which were troop carrying Landing Craft

Assault - LCAs and 3 Landing Craft Support (Medium) - LCS (M)s, which provided

heavy machine gun covering fire.

[Photo;

A fleet of

Landing

Craft

Assault

passing a

landing

ship

during

exercises

prior to

the

invasion

of

Normandy.

King

George VI

(not

visible)

is taking

the salute

on board

the

headquarters

ship HMS

BULOLO at

Beaulieu

Roads. Several of

the LCAs

were from

the 524

Flotilla; 654,

1254,

926, 1009,

920,

602,

656 and

921.

© IWM (A 23595)].

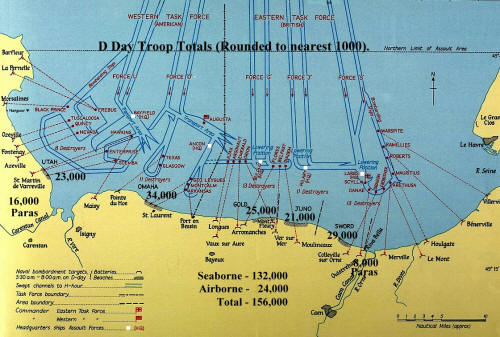

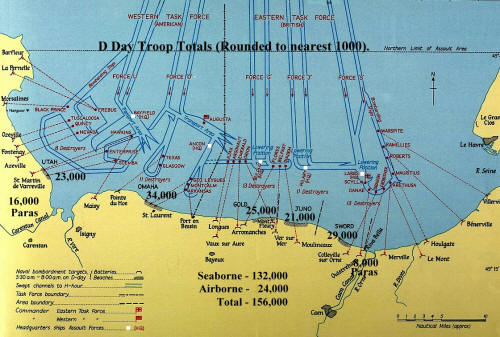

The flotilla took part in the initial assault

landings on Gold Beach (see map below) on D-Day against heavily defended enemy positions.

Each LCA carried around 35 fully laden assault troops amounting to over 500 in

total.

All the craft, their crews and troops were carried to Gold beach on their

'mother ship', the SS

Empire Arquebus. The full flotilla comprised LCAs 602, 654, 656, 663, 733, 920,

921, 926, 1005, 1008, 1009, 1010,1026, 1254, &1384 plus LCM(3)s 78,

109 & 112.

Until the beaches and their

environs were cleared of the enemy, all approaching landing craft were

potentially exposed to enemy mortars, 88mm shells, machine gun and

occasional heavy calibre shell fire. There was less enemy air activity than

anticipated. The

first account of 524 LCA Flotilla's D-Day experience is

by the

Officer

in Charge of LCA 1026, Sub Lieutenant Murray and the second is by former Royal Marine HR ‘Lofty’ Whitting who was

on board one of the LCS (M)s.

D-Day D-Day

While larger landing craft and ships made their own way

across the English Channel to Normandy, those in the 524 Flotilla were carried

on a large mother ship. Having attained a predetermined position several miles off the

Normandy beaches, at 0615 hours, 1026 and her sister craft were lowered fully

laden into the water by means similar to lifeboats on passenger carrying ships.

The craft then assembled into a strict order and, under their own power, proceeded

towards pre-determined positions on the landing beaches.

On arrival at the beach, the

troops were disembarked as close to their battle objectives as possible in

accordance with the meticulous plans of Operation Neptune,

(the amphibious phase of Operation Overlord),

prepared months in advance.

The initial beaching, at 0710, was carried out successfully, despite heavy

mortar fire from the enemy defences and strategically placed beach obstacles

designed to impede or prevent landings. After disembarking our assault troops, the Flotilla formed up again about a

mile from the beach (Jig Green), where we waited two and a half hours for the larger LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) to arrive

with their cargoes of troops. Our task was then to ferry the troops from the

LCTs

to their designated landing beaches. Our

Flotilla Officer (FO) controlled the movement of his craft on instructions from

nearby HQ ships, whose personnel were informed of the progress of battle and the

movement of vessels in their area. I loaded up with 25 troops. Their Commanding

Officer ordered me to beach on Jig Green, to the west of Le Hamel. LCTs

to their designated landing beaches. Our

Flotilla Officer (FO) controlled the movement of his craft on instructions from

nearby HQ ships, whose personnel were informed of the progress of battle and the

movement of vessels in their area. I loaded up with 25 troops. Their Commanding

Officer ordered me to beach on Jig Green, to the west of Le Hamel.

[Photo;

Lieutenant Commander J C Haans Hamilton, RNVR, and Major Clayton,

Royal Engineers, studying one of the obstacles with attached mines at low tides.

© IWM (A 23991)].

The tide had risen and

the beach obstacles in the form

of steel girders were now just below the waterline as

we approached the beach. This was a much more hazardous situation than on our

first approach to the beach a few hours earlier. With a bowman on lookout, I carefully steered

our LCA towards the beach but our luck ran out when our craft stuck fast on a

steel girder protruding through the bottom of the boat aft by the

starboard bilge pump. We were about 20 yards from the beach. Leading Seaman Williams

used the power of the LCA's two engines to break free, but to no avail. When

stoker Moule reported that the gearbox of the starboard engine had broken down

and the Port engine had seized up, it was time to disembark!

The

ramp was lowered and the army officer in charge,

accompanied by one of his troops, waded ashore followed by a sergeant who was hit in the

arm by a sniper. Although not seriously wounded, he fell down by the cockpit.

The bulk of the troops were, understandably reluctant to leave the relative

safety of the craft but it was imperative for them to do so before the craft

sank or was hit by mortar fire. I ordered the troops to disembark and

three

more left and were shot by the sniper(s) from

a pill box at Le Hamel. Using a Lewis gun, fire was concentrated on a pill box

on the extreme end of the wall, while the remaining soldiers disembarked and

waded ashore to take cover behind an overturned Sherman tank, which lay directly

in front of the our craft. more left and were shot by the sniper(s) from

a pill box at Le Hamel. Using a Lewis gun, fire was concentrated on a pill box

on the extreme end of the wall, while the remaining soldiers disembarked and

waded ashore to take cover behind an overturned Sherman tank, which lay directly

in front of the our craft.

We were at the mercy of the wind and tidal currents and our craft swung round

towards the pill box with about 2 feet of water inside. We were sinking rapidly.

The sniper was still firing at the boat and I hailed the soldiers to return

fire, but they were disinclined to do so.

[Photo; war grave of Able Seaman Bayliss at Bayeaux

cemetery, courtesy of Ian Murray].

I gave the order to abandon the craft, leaving the

wounded sergeant under

cover in the boat. It was impossible to drag him ashore and I considered that,

for the time being, it would be safer for him to remain in the craft.

Able Seaman Bayliss, the bowman in the boat, was shot and died instantaneously.

As I picked him up, I saw that the bullet had penetrated over his top left

rib and into his heart. I laid him down inside the craft and ordered stoker Moule to go over the stern,

which was less exposed to the sniper

and to crawl ashore. He safely reached the shore but lost the Lewis gun in the

process of getting there. I took the same route ashore with the other Lewis gun,

which I left behind with the troops on the beach. Next was Able Seamen McCarroll, Taylor and finally, Williams. We

all managed to gain the shore safely, by which time the boat rested on the bottom in 2 feet of water.

I led the crew eastwards, along the shore towards some beached LCTs,

hoping to obtain a lift back to our mother ship. On the way, we came across the Commanding Officer

of the 1st Hants, who had been wounded in the arm and leg during the assault

landing. We crawled another 600 yards along the

beach, where we met Sub Lt Laverton and his crew. Our relief was palpable.

We rested a while and then

proceeded further along the beach, where we came across the crews

of LCAs 602, 656, 920,1005,1008

and1010 who were all safe. All the

craft were stranded on the beach on the falling tide. After a meal, Leading

Seaman Williams took the crews to LCI 400 (Landing Craft Infantry), where they

remained, with the exception of the crew of LCA1010. I joined them later with Sub Lt

Chapman.

We received orders to report to the PBM (Principal Beach Master), who

controlled all traffic on the beach. We mustered all 524 LCA crews on the beach

with the exception of 663 and 1010. The crews of the stranded craft

still in working condition, were to remain on the beach until the craft could be

re-floated on the next rising tide, while the four remaining crews were to embark LCT 472. Sub Lt Davis

was informed of the arrangements and Able Seaman Giddings took charge of the

departing party comprising the crews of LCAs 920, 1005, 1008 and 1026. They carried stores recovered

from the wrecked boats and

embarked the LCT.

Sub Lt Chapman and I returned to the LCI where Leading Seaman

Williams and Able Seaman Allen were attending Able Seaman N Davey, who was

suffering from shock. The craft's doctor advised that Davey should remain aboard

the LCI, which was due to sail for Southampton that evening.

That settled, the rest of us returned to the

LCT, which was also to sail for Southampton that night. We

anchored off Calshot the following afternoon at about 1430, to see the Empire

Arquebus sailing past, heading for Cowes Roads. That settled, the rest of us returned to the

LCT, which was also to sail for Southampton that night. We

anchored off Calshot the following afternoon at about 1430, to see the Empire

Arquebus sailing past, heading for Cowes Roads.

[Photo; Lt Cmd DC Murray,

DSC, RN at Le Hamel pillbox].

We transported a "survivor" crew to

HMS Glenroy, where we

were looked after very well, returning about 2100, when a SNOT (Senior Naval

Officer Transport) arrived with his boat, to take us to the Arquebus.

My

men behaved exceptionally well during the whole period, in fact I cannot find

words suitable; they all deserve the greatest praise. Their spirit was grand.

Especially, Leading Seaman Williams and Able Seaman Allen, who carried out their

duties to the utmost of their ability as coxswains. I commend them for their

devotion to

duty during the whole period.

The 3 LCS(M)s

in support of the 15 LCAs, were crewed by Royal Marines. Their primary

task was to escort the LCAs to the landing beaches under cover of their heavy

machine gun fire. This is 'Lofty' Whitting's story of the same events. |

Urgent Appointment

Unbeknown to former Royal Marine, HR ‘Lofty’ Whitting, his

immediate preparations for D-Day began on May 30th 1944. His account

of events continues... Unbeknown to former Royal Marine, HR ‘Lofty’ Whitting, his

immediate preparations for D-Day began on May 30th 1944. His account

of events continues...

With several other Royal Marines, I arrived at the Royal

Marine Barracks at Deal to begin a routine junior NCO's course. The following

day, before our course had even begun, I and a few others were ordered to return

to our unit at Sandwich in Kent. We had no idea what was going on or what was in

store for us in the next few days.

The following day, we were instructed to proceed to Poole in

Dorset to locate the Royal Navy Landing Craft Assault (LCA) Flotilla 524.

Attached to this particular flotilla were three Royal Marine manned

LCS(M)s (Landing Craft Support, Medium), one of which, I was to join.

[Although not recorded in the author's account, the three craft

carried on the SS Empire Arquebus were the Mk3 LCS(M)s 78, 109 and 112. The

other craft on board were Landing Craft Assault or LCAs 602, 654, 656, 663, 733,

920, 921, 926, 1005, 1008, 1009, 1010,

1026, 1254 and 1384. Those shown in Red are

recorded as war losses sustained during the Normandy campaign. Lofty records

below that all the craft of 524 Flotilla survived the D-Day assault. Certainly

on June 19th 1944, the craft are recorded embarked in Arquebus but it

was on that day the ‘Great Storm’ hit the Normandy coast. It's possible that the

craft were lost during that three day period. Tony Chapman LST &

Landing Craft association. Opposite - colourised photo of LCA 1008].

The next day, I travelled to London and onward to Poole.

Arriving late in the afternoon I reported to the guard room and was given a

medical, a meal and a billet for the night. By then the 524 Flotilla had moved

to Hythe near Southampton! En route, I called at several camps including

HMS Mastadon (Exbury Hall) on the River Beaulieu. On arriving at Hythe, I

had more medicals and enjoyed the same lack of success in tracing the 524 LCA

Flotilla. Once more I was given a temporary billet for the night.

The following day, I discovered that my LCS(M) was on board a

ship in the Solent. I was taken to Southampton where a ‘liberty’ boat from SS

Empire Arquebus picked me up. As I climbed aboard I was asked, 'You know

where you're going tomorrow? Before I had time to reply the answer was

provided... France!' So I was to be part of the biggest amphibious

invasion force in history.

This was my first sight of an LCS(M), although I had been

trained to man these craft and knew what was expected of me. I was, therefore,

both unfamiliar with the craft and the men I would work alongside. These unusual

circumstances arose because I had replaced someone who had

failed to return to duty after home leave.

Familiarisation

The 524 Flotilla had 15 Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) manned by

the Royal Navy and our three LCS(M) manned by Royal Marines. The LCAs were

adorned with painted pictures and names of songs such as Blaydon Races, Suwannee

River and Polly Wolly Doodle.

Our crew comprised our officer, Lt Richard Hill, Corporal

Powell, Coxswain Andrews, Stoker Rowbotham, Marine Martin in charge of the CSA

Smoke-Laying equipment, Gun Loader Jock Smith, Signalman Crispen, Smoke Mortar

men Green and Howe and finally, Lewis gunners Pugh and myself - 11 in total.

Corporal Powell manned the twin 0.5 inch Lewis gun in the Boulton Turret.

Sunday June 4th was cold and miserable with heavy

rain, gale force winds and a very big swell on the sea. On the mess deck, at

breakfast, I met ‘Ginger’ Waters. He had been given a last minute draft at

Sandwich arriving on the Empire Arquebus during the hours of darkness.

Ginger was not familiar with LCS(M)s having trained as a gunner on Landing Craft

Flack (LCF), but thankfully his skills were transferable.

I spent that Sunday, June 4, scrubbing equipment,

familiarising myself with the craft, stowing away stores and attending meetings,

including a final briefing on our part in the great hazardous adventure that lay

ahead the following day. However, we learned that D-Day had been postponed due

to the bad weather so we attended more briefings and further studied our orders

and instructions. I went to bed early that evening but could not sleep.

D-Day

As I lay there, I felt the shuddering of engines and movement

as the ship set off. The Arquebus pitched and rolled in the rough waters

as we entered the channel. Curiosity got the better of me as I took in the

amazing sight of ships and craft of all shapes and sizes forming up in their

predetermined positions. Excitement gave way to exhaustion and I eventually fell

sleep.

Reveille next morning, June 6th was about 0330. We

had a hearty breakfast of fried eggs and bacon with fried bread and butter. We

were back on deck and beside our craft by 0430. It was time to go. Fully laden,

we lowered away, slipped our lowering gear on reaching the water and cast off.

Under our own power we moved away from our mother ship, at times riding on the

crest of the waves and then slipping into a trough with nothing to see but sea! Reveille next morning, June 6th was about 0330. We

had a hearty breakfast of fried eggs and bacon with fried bread and butter. We

were back on deck and beside our craft by 0430. It was time to go. Fully laden,

we lowered away, slipped our lowering gear on reaching the water and cast off.

Under our own power we moved away from our mother ship, at times riding on the

crest of the waves and then slipping into a trough with nothing to see but sea!

The LCAs we were to escort into the landing beach were off

another ship, so we rendezvoused with them. The troops carried on the Arquebus were from the Hampshire Regiment but we had no idea who we were

escorting that fateful morning. We all felt very queasy and I was sick just

once. Mortar man, Howe, suffered most.

As we approached the beach, all hell let loose. The big ships

of the Royal Navy fired shells over our heads and rocket craft fired several

salvos, each comprising dozens of rockets quickly followed by an almighty

‘woosh’ and the sound of explosions on the beaches.

As our craft moved towards the beach, Lt Hill stood on the

deck by the 0.5" twin machine gun turret. It was firing towards the beach to

force the enemy to take cover. However, one enemy 88mm shell burst to our right.

In the belief that no two shells landed in the same place our officer ordered

the coxswain to make towards the shell burst. Fortunately, the coxswain did not

hear the order because another shell exploded in almost the same position! There

was also enemy machine gun fire to our right, which we could see hitting the

water. The cacophony of thunderous explosions required our officer to scramble

around the craft to deliver his orders to the crew.

We were sailing towards the village of Le Hamel, which stood on

the western flank of Gold beach. Our target was a pill-box on the top edge of

the beach in the sand dunes. I can see it now, with a lone house to the right of

it. This was our landmark and target, which I fired on with my Lewis gun until it

stopped. I immediately hit the ammunition drum on the gun to check if it was

empty or jammed. If it ran freely, the gun drum was empty, in which case I'd grab

another drum, flick it into position and resume firing.

By this time ‘Jock’ Smith, the gun loader beneath the turret,

had loaded the twin Vickers so Pughy, our other Lewis gunner and myself ceased

firing. Corporal Powell continued manning the Vickers. As we neared the beach, we

were ordered to cease fire but to ‘stand by’ in case we were needed. The main

job of escorting the LCAs to the beach was over, the assault troops of the 50th

Division were, by now, on the beach.

During the morning, we had shipped a fair amount of water,

although the cause was difficult to detect. We appeared to be sinking by the

bows and we could not get ashore. We signalled a nearby frigate for assistance.

When we pulled alongside, they pumped us dry. Meanwhile they

passed down a container of hot soup which went down a treat. Otherwise our daily

food comprised little blocks of concentrated meat, dried potato, tea mixed

together with sugar, 5 glucose sweets, a bar of chocolate and 5 cigarettes and

matches. Drinking water was stored in containers aboard our craft.

As the day wore on, the weather steadily improved, the rain

eased off and eventually stopped. By early afternoon the cloud was lifting and

the sun began to shine. We cruised around waiting for orders, while avoiding other

nearby craft. By the evening of D-Day, most of the enemy had been driven

from the beach area. We ventured in closer to the beach to find craft of every

description both on the beach and cruising around like us. An LCS(M) like ours

had sustained shell damage and lay capsized on the beach. Clearly her crew had

been less fortunate than us.

Later in the evening, we hove-to alongside the other two LCS(M)s of our flotilla and received the latest orders and instructions via our

officers. One signaller picked up news from a BBC newsreader who described the

masses of assault landing craft, sailing in formation towards the coast of

France, escorted on the flanks by miniature destroyers. That was us!

We tied up alongside an LCG (Landing Craft

Gun), a much larger craft with 4" guns and enjoyed a good night's sleep. At dawn

we patrolled the beach to lay smoke in the event of an air attack. Operating the

CSA smoke-laying gear was Marine ‘Mary’ Martin. This work was completed by

daybreak, so we continued patrolling the beach area awaiting further orders or

instructions to return to our mother ship

Empire

Arquebus.

Post D Day

When our work was finally done we were hoisted back on to the

deck of Arquebus with the rest of our flotilla, including the other two

LCS(M)s. All the craft returned safely but, sadly, one sailor named Bayliss was

killed and his boat officer injured. They were the only casualties sustained by

our flotilla. We were all relieved and thankful to have survived the extreme

danger of the initial assault landings. [AB Stanley Bayliss of

524 LCA Flotilla was a native of Minster Lovell in Oxfordshire, he was aged 19

on the day. He rests in the cemetery at Bayeux. Tony Chapman of the LST

and Landing Craft Association].

After several days of roughing it, we highly appreciated a good

wash, a change into clean clothes and a hot meal. We were all formally debriefed

by providing an account of the events of D-Day but we also had opportunities to

share our experiences informally with others. There was no counselling in those

days but these informal sessions were a very good substitute.

In the days following the initial assault landings, the enemy

were driven inland and the beach area became less hazardous but by no means

entirely safe. An increasing number of troops were now disembarking from large

landing craft directly onto the beaches. We returned to Southampton to embark

more troops for the passage to Normandy but, in the absence of the earlier

hazards we had faced, we thought that the job we had trained for was at an end.

Our job had been to escort the LCAs from the mother ship to the beaches and to

target known defensive positions and generally to help secure a

beach-head.

The first time I stood on terra firma after 5 days at sea,

mostly in a small landing craft, the land heaved and tossed as though we were

still riding the waves! We returned to Hythe at some point, where we lived under

canvas.

During this period, Hitler’s new secret weapon, the pilot-less V1 flying

bomb, terrorised those who heard its engine cut out before it fell to the

ground. We instinctively dived for cover under anything nearby, including the

small table in our mess tent! After our stay at Hythe, we were drafted back to

the SS Empire Arquebus. During this period, Hitler’s new secret weapon, the pilot-less V1 flying

bomb, terrorised those who heard its engine cut out before it fell to the

ground. We instinctively dived for cover under anything nearby, including the

small table in our mess tent! After our stay at Hythe, we were drafted back to

the SS Empire Arquebus.

[Photo; an LCA courtesy of

Ian Murray].

When the Arquebus was stood down, we sailed west along

the English Channel, passing Plymouth and Lands End, through the Irish Sea into

the estuary of the River Clyde to a berth in Helensburgh. Our craft were lowered

away for the final time and moored alongside nearby. It was sad to leave behind

the craft that had been our home and protector and, of course, to bid farewell

to the Empire Arquebus. We were soon on our way to HMS Westcliff,

in Essex.

Flotilla Report

by

AF Ferguson, Lieutenant RNVR, Flotilla Officer.

FROM: Flotilla

Officer, 524th LCA Flotilla.

TO: Commodore Force G

DATE: 11th June 1944

SUBJECT: REPORT AND OBSERVATIONS ON MOVEMENTS OF FLOTILLA.

Movements

of LCAs

The LCAs all beached to time after an uneventful run - in under

slight fire of various types. The boats beached among the obstructions but these

did not cause any casualties to craft.

A successful withdrawal was made by all craft. These craft, with

casualties on board, were returned to the ship and were hoisted on board, not

without difficulty. The remaining craft were formed up, in deteriorating weather

conditions, to await the arrival of the LCTs from the LSI. On their arrival,

groups of craft were detailed to each LCT and ordered to carry out a ferry

service until emptied.

By this time - about 1200 D Day - the wind had freshened and was

blowing from onshore from a North Westerly direction. Many vehicles were drowned

well off shore. The beach obstructions were awash with the mines on them. Craft

were stranded and sunk on and off the beaches. Sporadic shelling and sniping

added to the confusion.

Under these circumstances all the LCAs beached and unloaded

troops. Eventually, after several trips, all the LCAs except that of the

Flotilla Officer, were impaled on beach defences or on drowned vehicles, were

broached to or in some other way rendered inoperable.

The Divisional Officer collected the crews of the craft on the

beach and arranged for their accommodation and 'fooding'. Those crews, whose

craft were not severely damaged, were left with their craft. The remainder of the

crews collected the valuable stores from the craft.

These crews, with their

stores, were embarked on an LCT, which returned to the United Kingdom and thence

to the Empire Arquebus. These crews, with their

stores, were embarked on an LCT, which returned to the United Kingdom and thence

to the Empire Arquebus.

[Photo; 524 LCA Flotilla Jan 1944

(Not including the Marines of the accompanying LCS Ms), courtesy of Ian

Murray whose father is seated 8th from the left 2nd row. William Edward Lacey,

who celebrated his 21st birthday on D Day, was the coxswain on LCA 1010. 2nd

back row, 2nd from the right.Click to enlarge].

The Flotilla Officer reported the confusion to D.S.O. A.G. Jig Green and Commodore Douglass - The craft

lay off the beaches, effected self repairs until the weather moderated and then

resumed the ferry service p.m. on Wednesday, 7th June.

At high water p.m. 7th June, two beachhead LCAs were towed off by

the Flotilla Officer. By midday 8th June all the LCAs of the Flotilla, not sunk

or damaged beyond repair, were hoisted in the S.S. Empire Arquebus. A signal was

made to the PBM to this effect.

The three LCS (M)s were lowered to time and took station on the

starboard beam of the assaulting troops. On approaching the beach, the assaulting LCAs came under shell and small arms fire. The LCS(M)s engaged the MG (machine

gun) posts in succession until all of them were silenced. This was effected

after about one hour's firing. The LCS(M)s then lay off the beaches and laid

smoke when ordered to do so by Force broadcast wave. All LCS(M)s were hoisted on

the SS Empire Arquebus on the 8th. June, 1944.

Conclusion

It will be appreciated that in so brief a report, only the broad

outlines of movements can be given. All Officers stated that their Naval ratings

and Royal Marines worked hard in uncomfortable and difficult conditions with

unflagging zest and great cheerfulness. It is a pleasure to work with such men.

A list of recommendations for awards will be forwarded separately.

Postscript

Having recorded these recollections shortly after the 50th

Anniversary of the D-Day landings, I began to wonder if I had imagined it all.

However, during June of 1996 I contacted my D-Day commanding officer, Lieutenant

Richard Hill, RM.

We exchanged many memories of particular events and general

impressions. He himself had given thought to writing a book about his D-Day

experiences, but his memories, too, had become somewhat clouded by the passage of

time. However, the memories flooded back as we reminisced, confirming the truth

of our shared experiences.

We spoke of our LCS(M) taking water and going alongside a

naval vessel to be pumped out. Richard had told the story many times over the

years believing that our craft had hit something in the water or had been holed

by flak or machine gun fire. Having returned to the Empire Arquebus, he

found a bullet hole in one of his trouser legs and on further inspection three

bullet holes through our Battle Ensign flying from the stern!

He also told me that one craft of our group of three had been

forced to return early to the Empire Arquebus because her Vickers gun had

jammed. This craft may have been commanded by Lieutenant Blackler RM, the

remaining craft of our group being under the command of Lieutenant Dan RM.

[Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing Craft Association writes on August 25th

2007: I've been unable to determine which officers were

in command of specific LCS(M)s assigned to 524 Flotilla off Empire Arquebus].

Further

Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books

listed on

our

'Combined

Operations

Books'

page which

can be

purchased

on-line

from the

Advanced

Book

Exchange

(ABE)

whose

search

banner

checks the

shelves of

thousands

of book

shops

world-wide.

Type in or

copy and

paste the

title of

your

choice or

use the

'keyword'

box for

book

suggestions.

There's no

obligation

to buy, no

registration

and no

passwords.

Click

'Books'

for more

information.

Acknowledgments

Part I.

We are grateful to Ian Murray, son of Officer in Charge of LCA

1026, Sub /Lieutenant Murray, on whose recollections this account is based.

Approved by Ian Murray before publication.

Part II is based on material

supplied by former Royal Marine HR ‘Lofty’ Whitting (1994) and transcribed by

Archivist/Historian, Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing Craft Association (Royal

Navy). Further edited by Geoff Slee and approved by Tony Chapman before

publication with the subsequent addition of photographs and

maps.

|