The British Mk1 LCMs (Landing

Craft Mechanised), were allocated to the 601 LCM Flotilla. They were around

44 feet in length and 14 feet across the

bows, with a speed of around 7 knots. The vast majority of the 500 British built Mark1s

came from the workshops of the Great Western Railway at Swindon,

Wiltshire and from the Southern Railways workshops at Eastleigh, Hampshire.

The remainder were built in various metal-working establishments between 1940 and 1944.

[Photo

opposite is a Mk1 LCM. This particular craft took no part in the

D-Day operation, but LCM 229, the next in line, was ‘Leader’ of the 601 LCM Flotilla

because Flotilla Officer, Derek Green, RM, was aboard for the journey from Itchenor

on the south coast of England, to Normandy. Photo courtesy of Danny Lovell].

British

LCMs, designed by Thorneycroft, had a capacity to carry a 16 ton tank, 6 jeeps, 100 troops

or general supplies. Pennant numbers, in the range LCM 1 through to LCM 500, were

allocated to these craft. They were powered by two Thorneycroft, or Chrysler, petrol

engines, producing around 120

brake horse power (BHP) delivered through twin shafts. They carried two .303

calibre Lewis machine guns and had a crew of 6 men, with an officer assigned to every third craft.

American Mk 3 LCMs,

which also formed part of 601, were designed by Andrew Higgins.

He also designed and built the LCVP (Landing

Craft Vehicle (Personnel), the USA equivalent of the British LCA (Landing Craft

Assault). Many LCM3s served with the Royal

Navy and Royal Marines under the American "Lend-Lease" scheme. They were 50 feet in length by 14 feet

across the bows and were driven by two diesel engines producing up to 450 BHP

with a speed of between 8-11 knots. They carried two .50 calibre machine guns.

They could carry a 30 ton tank, wheeled vehicles, 60 troops or general supplies

and had a crew of 3 men.

American Mk 3 LCMs,

which also formed part of 601, were designed by Andrew Higgins.

He also designed and built the LCVP (Landing

Craft Vehicle (Personnel), the USA equivalent of the British LCA (Landing Craft

Assault). Many LCM3s served with the Royal

Navy and Royal Marines under the American "Lend-Lease" scheme. They were 50 feet in length by 14 feet

across the bows and were driven by two diesel engines producing up to 450 BHP

with a speed of between 8-11 knots. They carried two .50 calibre machine guns.

They could carry a 30 ton tank, wheeled vehicles, 60 troops or general supplies

and had a crew of 3 men.

Preparations for D-Day

Prior to June 6th 1944, the 601 LCM Flotilla

was based at Shoreham Harbour on the south coast of England, to the west of

Brighton. In a later re-organisation of ‘F’ Build-Up Squadron, of which '601' was part, they moved to shore base HMS Sea Serpent

at Bracklesham Bay, where the craft were moored at Itchenor Creek, near

Chichester. During this period, exercises and practice landings were routinely

conducted. Half the men and craft of the 601 also took part in the review of

the Invasion Fleet by King George V1, just before D-Day. At that time, the

flotilla complement was 6 officers and 156 other ranks, including reserve crews.

Shortly before D-Day, the administration

officer, reserve naval officer and reserve crews, boarded a troopship, while the

engineer officer, with part of the maintenance party, joined a workshop barge,

all with the intention of rejoining the flotilla after the initial landings.

Around the same time, the craft of 601 carried out loading operations in the Solent, with

payloads varying from transport vehicles for beach parties, command trucks for

the assault tanks, ammunition trailers pulled by jeeps and crated ammunition to

replenish supplies following the initial assault.

Shortly before D-Day, the administration

officer, reserve naval officer and reserve crews, boarded a troopship, while the

engineer officer, with part of the maintenance party, joined a workshop barge,

all with the intention of rejoining the flotilla after the initial landings.

Around the same time, the craft of 601 carried out loading operations in the Solent, with

payloads varying from transport vehicles for beach parties, command trucks for

the assault tanks, ammunition trailers pulled by jeeps and crated ammunition to

replenish supplies following the initial assault.

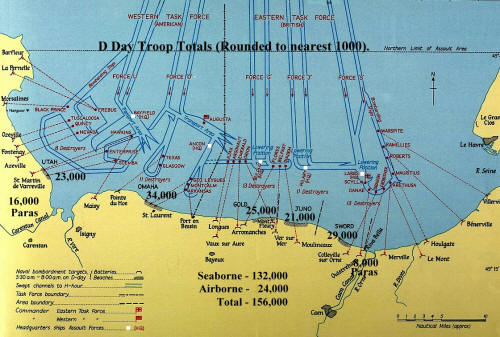

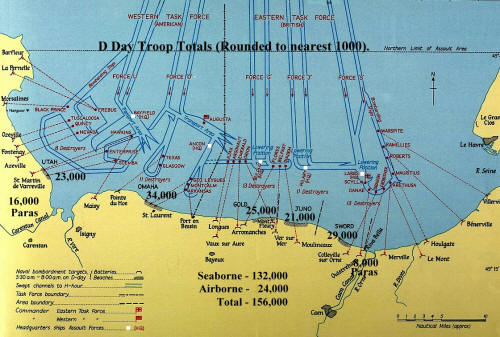

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

On June 2nd 1944, a briefing took place at HMS Sea Serpent

about the landing beaches, enemy defences and the opposition likely to be

encountered. The invasion was planned for June 5 but was rescheduled for June 6

due to bad weather. However, many craft had already set out, which added to the

discomfort of the men, who, by then, had been confined to their craft for four

days for reasons of security.

Finally, on June 5th, the eve of D-Day, the 16 Mk1 LCMs of

the 601 LCM Flotilla,

accompanied by their sister craft of the 600 and 604 Flotillas and the Mk3 LCMs

of 650, 651 and 652 Flotillas, weighed anchor and proceeded in single line

ahead down Itchenor Creek, having exited from Birdham Pool. The captain of HMS

Sea Serpent took the salute from each craft as they passed the pier-head.

Finally, on June 5th, the eve of D-Day, the 16 Mk1 LCMs of

the 601 LCM Flotilla,

accompanied by their sister craft of the 600 and 604 Flotillas and the Mk3 LCMs

of 650, 651 and 652 Flotillas, weighed anchor and proceeded in single line

ahead down Itchenor Creek, having exited from Birdham Pool. The captain of HMS

Sea Serpent took the salute from each craft as they passed the pier-head.

[Photo; Flotilla Officer,

Captain, Derek Inglis Green with a page from the Admiralty's list showing the

disposition of 601 Flotilla just prior to D-Day].

The full complement of ‘F’ Build-Up Squadron

comprised 96 Mk1 LCMs

- 6 flotillas of 16 LCMs, each craft with a 6

man crew - a coxswain, stoker/driver and 4 deck hands. Every third

craft carried a boat officer, the three craft together being a sub-division of

the whole; a total of 608 men. Whether or not each and

every single craft assigned to the squadron was present when they set out, cannot

be confirmed. According to official records, at the point of departure, 601 LCM

Flotilla comprised Mk1 LCMs 166, *168, *180, 199, *216, *226, *229, 238, 256,

266, 276, 298, *330, 339, *346 and *383. [* signifies War Loss in Normandy

during June/July 1944].

On

board LCM 229, was 22 year old Flotilla Officer, Captain Derek Inglis

Green, RM, making the craft ‘Flotilla Leader’. Green was born in the

village of Ben Rhydding near Ilkley, on the outskirts of Bradford, West

Yorkshire. He was educated at the famous Rugby Public School in Warwickshire, immortalised in the famous book ‘Tom Brown's Schooldays’ by Thomas

Hughes. Green joined the Royal Marines in May 1941, prior to which he had worked in

his father’s firm of timber merchants at Silsden, Keighley, Yorkshire. His

brother, Captain Jack Green, had been taken prisoner in 1943 while serving with

an infantry regiment. Their father, John Green, had once been captain of the

Yorkshire and England rugby team.

D-Day

After departing Itchenor, the squadron proceeded to the rendezvous

point for FORCE J (Juno beach) about 2 to 3 miles off the Nab Tower,

eastwards of the Isle of Wight. The craft carried extra fuel

for the sea trip in Jerry cans strapped into every available space.

After departing Itchenor, the squadron proceeded to the rendezvous

point for FORCE J (Juno beach) about 2 to 3 miles off the Nab Tower,

eastwards of the Isle of Wight. The craft carried extra fuel

for the sea trip in Jerry cans strapped into every available space.

On June 6th 1944, at around 0400 hours, the

craft moved out for their journey to the beaches of Normandy. Weather and sea conditions,

although better than the previous day, were still difficult and the craft

experienced problems maintaining station in the line. Because of this, the craft

of 601

proceeded independently for the Normandy beaches, navigating along one

of the 'swept' channels cleared of enemy mines. However, some of the craft soon found

themselves in difficulty.

Captain Green's 'Leader' LCM 229, with Marine Coxswain F J Dorrel, boat officer

Sub. Lt Page, RNVR and Sub. Lt Herbert Pye, RNVR, broke down in mid-channel. The

crew were picked up by the minesweeper, HMS Poole. LCM 346, whose

complement included Marines, Timms and Billingham, arrived off Juno beach at 2030

hours on the evening of June 6th. However, she collided with

another craft and holed badly portside (left) stern. The crew were picked up by the USLC(G)

893. It is likely

that LCM 346 was no longer operational, being officially recorded as damaged beyond economical

repair.

Despite the unfavourable sea and weather conditions,

the other craft found their way to their pre-determined landing places on Juno beach in the late evening of D-Day. Initially,

they came under fire and bombing but their cargoes were successfully put

ashore. Enemy activity was later reduced to 'hit and run' air attacks involving anti-personnel bombs and machine gun

fire,

especially at night. However, in the event, the hazards of the sea, the weather and the

landing beaches, proved to be a greater danger than enemy activity.

Initially, the men of 601 LCM flotilla and those of

other nearby flotillas, lived aboard the Depot Repair Ship, SS Ascanius.

It arrived off Juno Beach on the morning of June 8th, having departed the River

Thames the previous day to take up her station at Gooseberry 4... a position

inside the Mulberry A harbour.

During the

severe storm that swept the Normandy coast between June 19th-22nd, many craft were damaged or driven ashore and wrecked.

The crews of 601 transferred to the shore, where they lived in dug-outs in a field

near Bernieres-sur-Mer Railway Station. Martin Tyrell recalled that during the 3 day storm, 8 craft of the flotilla

were lost, but official records available on 601, do not confirm this.

In all, the craft of 601 remained on station for a period of 6 weeks,

during which time, save for brief intervals for rest and recuperation, they ferried

every conceivable type of stores and equipment from supply ships to the

beaches. As the need for 'ferrying' craft diminished, the number of LCM Squadrons

was halved and the surplus craft ordered back to England. 601 was included in

these arrangements and possibly elements of 650 LCM Flotilla, leaving the

remainder of F Squadron in place on Juno beach.

Return

to Blighty

For the homeward journey

from Normandy,

selected unmanned LCMs were assigned to

the much larger LCTs (Landing Craft Tank) for towing back to England, while

others would proceed under their own power. By the evening of July 20th, the

craft of 601 were lying in Gooseberry 4, stored and

provisioned for the journey. The LCMs were paired up for the short trip to the LCTs

anchored nearby - a manned LCM with an unmanned LCM alongside.

The LCMs were not in good condition after 6

weeks of intensive ship to shore ferrying, often in rough seas and high winds...

and there had been little time for servicing and repairs. 601 veteran, Royal

Marine, Jim ‘Nobby’ Clark, confirmed that his LCM had seen better days and was

not in very good condition. It was one of those lost on the homeward journey.

At 0430 hours on the morning of July 21st 1944,

the Flotilla weighed

anchor and proceeded independently to rendezvous with the LCT Flotilla, just off the beach-head. The task of transferring the unmanned craft to the LCTs, was completed by 0540 hours

and the manned

LCMs formed up astern

of one of the LCTs. A course was set through the swept channel but a thick blanket of mist descended which made

it extremely difficult to keep on station. This raised concerns about craft

becoming lost, so, for safety reasons, at 0700 hours, the decision was taken to

anchor. By 0930 hours, the mist had cleared sufficiently to allow the flotilla

to resume its journey.

A total of 15 manned LCMs formed part of the homeward bound convoy, including ‘Leader’ LCM 1059 carrying Flotilla Officer, Captain Green. The 1059

was a Mk3 LCM, an American built, diesel driven craft of 651 LCM

Flotilla. It was larger and more powerful than the British LCMs and had been seconded for the journey home,

because it had superior navigation capabilities.

As the day wore on the weather deteriorated.

At first the sea was calm with a rather heavy

atmosphere and then the conditions deteriorated with heavy, turbulent seas and thunderstorms. By 1720 hours, the sea was so rough that

there was little or no headway being made, despite engines on full throttle. It was decided

to return to Juno beach, not the least of the

considerations being that petrol supplies for the

British Mk1 LCMs were running low.

All Haste to Juno

Prior to giving the order to turn about,

Captain Derek Green, still aboard LCM 1059, fell out of line several

times to round up stragglers and when the craft had re-grouped, a

course was set for the beach-head. By this time they had been at sea for thirteen hours and

some LCMs were having difficulty keeping up. One LCM developed

engine trouble soon after they had turned about and Sub Lieutenant Colin

Backhouse, in LCM 226, turned back to render assistance. The decision was made to

take the crew off the crippled craft and the manoeuvre was started.

Unfortunately, 226 collided with an unknown craft causing damage to its stern, which put her

steering out of action. The rescue craft had become unmanageable and was now, itself,

in need of assistance.

LCM 1059 went alongside to

render assistance and both crews were lifted aboard to safety, increasing her

human cargo to three officers and twenty nine other ranks comprising her crew,

the rescued men, the reserve crew and part of the flotilla administration staff.

While LCM 1059 was engaged in this operation, Captain Green ordered the rest of

the flotilla to return to the beach-head with all speed. Most of the craft and

crews were suffering badly from the rough sea, strong winds, heavy rain and sea

water pouring over the sides. The craft soon became dispersed in the darkness

but 5 craft eventually reported back to the squadron, while others reached the

beach-head at various points.

[Here the

historical record is far from precise. On the one hand it's claimed that 11

craft were lost on passage home, but that detail did not form part of Martin

Tyrell’s recollection of events].

LCM 1059 - A Fateful

Decision

On completion of her rescue operation, LCM 1059 was isolated in the darkness

of the English Channel with her, then, complement of thirty two men. Her

remaining fuel was sufficient for the journey home to England and for around

three hours reasonable progress was made. However, the craft was becoming

increasingly sluggish due to water entering the aft

ballast tank through a leak in

the propeller gland. Attempts to stem the leak proved

fruitless, so lifebelts were issued to the men, many of whom required assistance

because they were too overcome by sea-sickness. At 21.30 hours on the evening of July 21st,

LCM 1059 became

overwhelmed and sank.

Every man aboard had some buoyancy aid, such as a Mae West or a cork lifebelt,

but despite this, the sole survivor was Sergeant Latham. He later recalled that

spirits were high when the decision was made to continue on to England. The men felt that their stronger, more powerful craft, could safely complete

the journey, while the

remainder of the flotilla, in the less sturdy Mk1 LCMs, sought

the relative safety of the Normandy beaches. It was a tragic twist of fate for

the men of 601 LCM Flotilla who, 3 hours earlier, had suffered the loss of LCM

226, experienced the joy of rescue by LCM 1059, only to find themselves once more

at the mercy of the turbulent seas.

"Lady Luck" smiled on Sergeant Latham the following morning, when he was picked up at

first light. Visibility was very poor, but he had drifted into the path of a motor launch

patrolling off the beach-head. The launch immediately conducted a search of the

area with the help of Coastal Air Forces from Portsmouth, but sadly, all to

no avail. [See Correspondence

for 2016 message from Sgt Latham's son].

Veteran Royal Marine,

Stoker, Jim ‘Nobby' Clark, was amongst the men of 601 who safely reached Juno beach.

He could not remember how long he had been in the water, or when he had been

pulled clear by a rescue tug, but he did recall seeing the body of

Flotilla Officer, Captain Derek Inglis Green, floating by, as the tug moved away.

His body was never recovered.

Veteran Royal Marine,

Stoker, Jim ‘Nobby' Clark, was amongst the men of 601 who safely reached Juno beach.

He could not remember how long he had been in the water, or when he had been

pulled clear by a rescue tug, but he did recall seeing the body of

Flotilla Officer, Captain Derek Inglis Green, floating by, as the tug moved away.

His body was never recovered.

[Photos left; Nobby Clark in his "khakis" and

"blues" courtesy of his son Jim].

It seems that, when Jim was picked from the water,

he was in a state of shock, since he could not recall the name of his craft or five comrades.

Later, he met Sergeant Latham and only then did he appreciate the full horror of

what had taken place the night before.

Royal Marine Corporal, John Lordon, spent a considerable time at the mercy of the elements before being

retrieved from the sea. He never again saw active service. After recovering from

his ordeal, he spent the remainder of the war inducting new recruits into the

Royal Marines.

Royal Marine Corporal, John Lordon, spent a considerable time at the mercy of the elements before being

retrieved from the sea. He never again saw active service. After recovering from

his ordeal, he spent the remainder of the war inducting new recruits into the

Royal Marines.

[Photo right; Jim Colvin courtesy of his son James

Colvin].

The LCM which carried Royal Marine,

Jim Colvin, was taken in tow by a rescue craft, possibly a tug. Colvin and his

crew were later repatriated to England, where they, understandably, asked questions about the fate of their comrades on

July 21st. His persistence appears to have earned him a reputation as

a ‘trouble maker’ and his questions remained unanswered. He was later

transferred to the Far East. At the end of the war, h e

returned his campaign medals to the War Office in protest against the apparently

indifferent attitude of the military authorities and their silence on the

matter. Jim Colvin’s son recalls that his father made it quite clear to the War

Office where they could stick his medals!

e

returned his campaign medals to the War Office in protest against the apparently

indifferent attitude of the military authorities and their silence on the

matter. Jim Colvin’s son recalls that his father made it quite clear to the War

Office where they could stick his medals!

Bournemouth man, Royal Marine, John William Collins

(left),

worked locally before

he volunteered to join the Royal Marines in 1939.

He was known to

friends and family as ‘Bill’ and was engaged

to be married to Eileen Lodge. He

served in 601 LCM

Flotilla and, sadly, was

amongst those lost at sea on the night of 21st July 1944.

A Close Encounter

Corporal George

Morrison, RM. For some time prior to June 6th, Morrison was employed as flotilla clerk. He was regarded as Number 1 Reserve Coxswain in charge of

the Number 1

Reserve Crew, and as such, was not part of a specific crew, so an LCM was not allocated to

him.

Prior to setting off for Normandy, Captain Green gave permission for Morrison

to

take passage with his friend, Lance Corporal, Thomas Langan. They had been

great friends since they ‘joined up’ together in May 1943, but immediately prior to departure, the decision was reversed and

Morrison took passage in the LCM of Coxswain Lance

Corporal Bambrick. That change of mind by Captain Green, doubtless saved Morrison’s life,

since Lance

Corporal Thomas Langan, and his crew, perished in the storm.

Morrison recalled that, on July 21st 1944, the weather

was

sunny but later it became very foggy making it difficult to see the craft ahead of them. While struggling in the fog, Bambrick's craft hit some

obstruction, possibly the craft ahead of

them. They immediately reduced speed and soon after they lowered the

Kedge anchor to wait for the fog to lift.

When the fog eventually lifted, Bambrick's LCM was by itself. The LCT

that had been guiding them, had disappeared and no other craft or ship was in

view. They resumed passage to England using a due north compass bearing. It

might not take them back to the safety of Itchenor, but they would certainly arrive somewhere on the

south coast of England.

During the

afternoon, a landing craft was sighted ahead of them. It appeared to be

abandoned, with its Kedge anchor down and the cable apparently wrapped around

the screws. They went alongside in the hope of finding petrol to supplement

their diminishing supply. However, the sea

had turned decidedly rough, and attempting to pull alongside was not easy. After several aborted attempts, the idea of tying

up alongside was abandoned. In the absence of volunteers, Morrison decided to

jump aboard as the two craft moved together. The first pass failed, but on his

second attempt, he was successful and he immediately began checking the petrol

supply. Most of the cans were full and they were quickly transferred. When

completed, Morrison returned to his LCM by the same dangerous process.

Later that day, the stoker/driver reported that

one engine had stopped and would not re-start, but he thought the craft could

still maintain headway and continue her journey to England. As day turned to

night, the storm increased in ferocity and eventually all

the crew were overcome by sea-sickness, with the exception of Morrison himself. Throughout the period, he

stood in the cockpit facing the wind, constantly chewing

hard biscuits. It was that, he believed, that kept the sea-sickness at

bay. The memory of that night of July 21st 1944, never left him The waves were enormous and rose well

above the ramp. At times he had serious doubts about their survival.

Morrison had never been so scared in all his life and the fact that the remainder of

the crew were overtaken by sea-sickness, and unable to share his concerns, did not help.

They appeared to be quite oblivious to

the enormity of the situation they were facing. It is often said that people

near to death by drowning see their life pass before their eyes. It was

certainly true for Morrison that day.

By the morning of July 22nd, the storm had

abated and the crew had recovered. Throughout the night, the stoker/driver had

managed to keep the one engine working, despite spending the night in the engine

room, vomiting into a bucket firmly clasped between his knees. But their

problems were only beginning. Shortly after daylight, the stoker/driver

reported that the second engine had stopped and

would not restart. Lance Corporal Bambrick's LCM was now without power and

drifting. The spirits of the men, already low, dropped further when it was

noticed that the bows of the LCM were getting lower in the water. Their craft was

taking in water forward and there was no means of stopping it.

They concluded that the bows had been damaged the previous

day, causing the forward bilge tanks to fill up. Later in the day, when

the sea became choppy, more water was washed aboard, causing the bows to

sink even lower in the water. It was agreed to lighten the LCM by

throwing all unused petrol cans, kit bags and rifles over the side. Boots were

removed and the men put on their ‘Mae Wests’ and made ready to ‘abandon ship’ if

required to do so.

On the point of despair, salvation came initially as smoke on the horizon, which

later transpired to be small ships in ‘line abreast’ formation. The ships were a fleet of

minesweepers going about their business. Bambrick's LCM had drifted into an

un-swept channel! The signalman made contact with the minesweepers using SOS and

one of them came

alongside to take the LCM in tow. The plan was soon aborted when the speed of

the minesweeper began pulling the LCM under. The minesweeper stopped, pulled the LCM alongside

and took off her crew.

A jar of Rum was immediately produced and the crew of the LCM were ‘ordered’

to drink. They were soaked to the skin and their uniforms were white with

salt. At the time, Morrison was a teetotaller but the Rum made him feel much

better, even though he hated the taste. Despite the beneficial effect of the rum,

he never drank the stuff again. He reported to the Captain and gave an account of events that had taken place

from the point of departing Juno beach until the SOS was picked up. Arrangements were put in hand to check the landing craft's engines

and the degree of flooding.

The LCM crew borrowed some naval uniforms while their own dried

off and they were given a first class meal in the seamen’s mess followed by a

well earned sleep. Space was limited, so Morrison

slept on a steel companion-way above the engine room. The LCM crew were so tired

they could likely have slept standing up !

The following day, Morrison was informed that the landing craft had been

pumped dry but that both engines were still refusing to work and were beyond

repair. A tug was called-up to tow them back to Juno beach to join up again with 601 LCM Flotilla. Back in their own uniforms

again, the crew left the minesweeper to take passage on the tug, with two

volunteers from the LCM crew manning the landing craft.

Later that day, they arrived back on Juno beach to be met by Lieutenant

Martin Tyrell, who, to their great surprise, was delighted to see them. It was

then that Morrison and Bambrick and the other crew members of the LCM were

given the news of the terrible loss of life during the storm and that they

themselves had been posted ‘Missing Presumed Killed’. Later, with the rank of Captain, Martin

Tyrell took command of 601 LCM Flotilla, replacing Flotilla Officer, Derek Inglis

Green, lost on July 21st 1944.

Eventually, Morrison and the other survivors from the landing craft found

themselves back in England. During the passage home the weather was typical of

summer... no wind, no rain and a calm sea. After arriving back in Portsmouth

they made their way back to the place where it all began - Itchenor.

Roll of Honour

601 LCM FLOTILLA

JULY 21st 1944

Royal Marine Captain Derek Inglis Green.

Sub. Lt Colin Backhouse RNVR.

Royal Marine Lt. Edward Mears Aylan-Parker.

Royal Marine Sergeant Frank Harris.

Royal Marine Sergeant Ernest Spence.

Royal Marine Corporal Arthur Tidy.

Royal Marine Corporal Joseph Barber.

Royal Marine Eric Beadle M.I.D.

Royal Marine Edward Knight.

Royal Marine John Tillie.

Royal Marine Maurice Bradshaw.

Royal Marine John Collins.

Royal Marine Ralph Jellicoe.

Royal Marine Thomas Lowe.

Royal Marine Kenneth McKenzie.

Royal Marine John Marshall.

Royal Marine Jack Pattison.

Royal Marine Daniel Sharp.

Royal Marine Ronald Smith.

Royal Marine Peter Brookman.

Royal Marine Jack Child.

Royal Marine William Dunwoody.

Royal Marine Hillary Edwards.

Royal Marine William Goddard.

Royal Marine Thomas Hamilton.

Royal Marine Reginald Holmes.

Royal Marine William Stewart.

Royal Marine Harvey Taylor and

Stoker Thomas Race RN.

FRANCE

Royal Marine Lance Corporal Thomas Langan

and

Royal Marine Ronald Andrews.

650 LCM FLOTILLA

AT SEA

Royal Marine Corporal William Daw.

Royal Marine Walter Tillett.

Royal Marine John Petrie.

Royal Marine James West and

Royal Marine William Turnbull.

FRANCE

Royal Marine Henry Diviny

THE ROYAL MARINES PRAYER

O Eternal Lord God, who through many

generations has united and inspired the members of our Corps, grant thy

blessing, we beseech thee, on Royal Marines serving around the Globe. Bestow

thy Crown of Righteousness upon all our endeavours and may our Laurels be

those of gallantry and honour, loyalty and courage. We ask these things in

the name of Him, whose courage never failed, our Redeemer, Jesus Christ,

Amen.

FOR THE FALLEN

by

Laurence Binyon

They shall grow not old

As we that are left grow old

Age shall not weary them

Nor the years condemn

At the going down of the Sun

And in the morning

We will remember them.

The Itchenor Memorial

In 1951, a memorial seat was donated by the ‘D-Day Survivors Society’.

They wished

to remember their fallen comrades and to acknowledge the kindness shown to them by the residents of Itchenor

during preparations for the invasion of Normandy. The

memorial seat overlooks Chichester

Harbour and on July 21st 1951, seven years to the day after the tragedy, it was

dedicated. Since that event, an annual service has

taken place within the first week of June. [Photo below; Captain Angus Forrest, RM,

taking the salute at the 1951 ceremony].

IN MEMORIAM

601 ROYAL MARINE

LANDING CRAFT

FLOTILLA

IN MEMORY OF THE

OFFICERS

AND MEN OF

THE ROYAL NAVY AND

ROYAL MARINES

WHO LOST THEIR

LIVES

WHEN RETURNING FROM

THE NORMANDY

BEACHES ON

JULY 21st 1944.

Before the unveiling of the seat. [Photo

courtesy of Steve Knight].

The first dedication ceremony on July 21st 1951 with Lieutenant Martin

Tyrell (later Captain), of 601 LCM Flotilla, standing immediately behind and

to the left of the presiding vicar.

[Photo courtesy of Chris Bradshaw, grandson of Maurice Bradshaw].

Enlarged photo of Captain Angus Forrest, RM, taking the salute at the

ceremony. [Photo courtesy of Chris Bradshaw, grandson of Maurice Bradshaw].

Veteran Royal Marine, Reg Blake, who served with 803 LCV(P)

Flotilla off Normandy. When he passed through Itchenor in 1976, he saw the

dilapidated condition of the seat dedicated to the men of the 601 LCM Flotilla and resolved

to do something about it. Together with friend Dennis Drew, and

with the help of the Royal Marines' "Globe & Laurel" magazine, local newspapers and

the local council, he raised the funds from

local people and ex-paratrooper David Purley GM who became famous in the world

of motor racing. Purley was awarded the George Medal after attempting to rescue

fellow racing driver, Roger Williamson, following a fatal crash during the 1973

Dutch Grand Prix. On

June 6th 1978, a brand new seat, far superior in quality to the original, was

dedicated. [These photos, left and below,

are courtesy of veteran RM Reg Blake].

Veteran Royal Marine, Reg Blake, who served with 803 LCV(P)

Flotilla off Normandy. When he passed through Itchenor in 1976, he saw the

dilapidated condition of the seat dedicated to the men of the 601 LCM Flotilla and resolved

to do something about it. Together with friend Dennis Drew, and

with the help of the Royal Marines' "Globe & Laurel" magazine, local newspapers and

the local council, he raised the funds from

local people and ex-paratrooper David Purley GM who became famous in the world

of motor racing. Purley was awarded the George Medal after attempting to rescue

fellow racing driver, Roger Williamson, following a fatal crash during the 1973

Dutch Grand Prix. On

June 6th 1978, a brand new seat, far superior in quality to the original, was

dedicated. [These photos, left and below,

are courtesy of veteran RM Reg Blake].

Dr. Martin Tyrell reading the Roll of Honour of the men of the Royal

Marines and Royal Navy who were lost on July 21st 1944. Standing to his right is the Royal Navy Padre from

Portsmouth. On his immediate left is George Morrison and then John Roles who

also sailed in the 601 Flotilla.

Dr. Martin Tyrell reading the Roll of Honour of the men of the Royal

Marines and Royal Navy who were lost on July 21st 1944. Standing to his right is the Royal Navy Padre from

Portsmouth. On his immediate left is George Morrison and then John Roles who

also sailed in the 601 Flotilla.

Veteran Royal Marines of 803 LCV(P) Flotilla at the

Itchenor Memorial seat, Circa 1995. L - R were Phil Crampton, Andy Anderson, Ray

Hemsley, Reg Blake, Ken Reeves and Ron Dunham.

Veteran Royal Marines paying their respects to fallen

comrades on June 6th 2008. Standing on the extreme left of the group, next to the RM bugler, is

former Lieutenant (later Captain) Martin Tyrell, RM. Sadly he passed away in May 2009.

Three veterans of 803 LCV(P) Flotilla at Itchenor in 2008. In

the centre is Reg Blake, seen above in photo 3. With him were Ray (Yorkie)

Hemsley, left, and Phil Crampton, right.

2010 Service

A remembrance service, was held at

1100hrs on Friday 4th June at Itchenor Hard, to honour those members

of the 601 LCM Flotilla who lost their lives on the 21st July 1944.

The service was organised by Mr Peter Dean and Mr Peter Arnold, of the Itchenor

Society, and was attended by 190 people. The welcome address was given by Reg

Blake of the Royal Marines, followed by the History of the Memorial Seat by Lt

Col John Davis, OBE. Captain Johnny Talbot, RN, read the 32 names of the members of

the flotilla lost at sea. Mr Peter Dean, Chairman of the Itchenor Society, laid

a wreath on behalf of the residents of Itchenor. There followed the Last Post

and a one minute of silence before the Reveille. Finally, the Exhortation and

Prayers were led by the Reverend John Williams. [Photos below

courtesy of Peter Arnold, Honorary Secretary, Itchenor Memorial Society].

Dear Geoff

I thought you might be

interested in the Order of Service I produced for the 75th

Anniversary (7th June 2018) of the 601 LCM Flotilla disaster. We

normally hold a brief service at the Memorial bench in Itchenor but, because

the weather was dreadful, it was moved to our church, St Nicholas. We had a

contingent of four Royal Marines from the City of London branch and over 200

people in and around the church.

For the last couple of years we’ve reduced the

service to placing a wreath on the memorial bench on 21st and

have a reading of the Marines prayer. I’ll send you a couple of photos of

this years’ service in due course.

[Photos courtesy of Peter Arnold].

Best wishes

Alastair Spencer

Men Who Sailed with 601 (and not included elsewhere in this account).

Royal Marine Corporal Arthur (Mick)

Victor Tidy, PO/X 118747, 601 LCM Flotilla. Died 21 July 1944, Age 19. His

name and details are on the 1939 - 1945 Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

Mick was the beloved youngest son in a family of five children

and all were devastated by his loss. What made his death more poignant for the

family was that he couldn't swim. However, he was very keen to do his duty and

to serve his country.

[Added here, in his memory, by his niece, Sandra Garrett].

Royal Marine Maurice Bradshaw

sailed with LCM 601 Flotilla and was

one of those who died on the 21st July 1944. Before the war he had been given a

trial for Portsmouth Football Club. In the photo opposite he is on the

extreme left of the front row. What the occasion was, or the identity of the

group, is not known for certain but thought to be an army football team.

Royal Marine William Alfred Goddard

was lost at sea on the 21st July 1944. He was born William Alfred Fletcher

but through adoption he became known by his new family as Peter Goddard.

[Photo courtesy of Duncan R G Jolly].

Royal Marine Edward Albert Knight whose name is on the Roll of Honour

above. [Photo courtesy of his nephew Steve Knight].

Flotilla Composition

For those with a deep interest in the subject, here are details of the craft

that formed 601 LCM Flotilla throughout the period June 5th through to July 31st

1944. For the period up to June 25, they are as recorded above in the text for

D-Day. After the severe storm, which raged for several days from June 19, the

composition of the Flotilla changed as craft lost or damaged were replaced.

Thanks are due to Mike Long who obtained the information from the National

Archive at Kew, London.

Normandy war losses from 601 Flotilla were listed as; 168, 180, 216,

226, 229, 330, 346 and 383 and from 650, LCMs

1197, 1212, 1240, 1278. Dispositions on key dates provide a timeline to

the above losses as below.

601 LCM Flotilla

24/06/44

168, 180, 199, 226, 266, 276, 298, 339, 346,

383, 387, 411, 428, 449, LCM(3)’s 502 and 511.

Leader LCM 229 is missing on the above date so

must assume that news of her loss had filtered through. LCM 346 seems to have

been non-operational since her arrival in Normandy on June 6th when she was

damaged....that situation appears to have continued throughout.

03/07/44

166, 168, 180, 199, 236, 238, 256, 266, 276, 298, 339, 346, 383, 411, 449.

On the above date166 and 168 recorded in need of repair. The 346 and 383

recorded damaged beyond economical repair.

10/07/44

166, 168, 180, 199, 236, 256, 266, 276, 298, 339, 346, 383, 411, 428, 449.

Recorded in need of repair on this date are 180, 236, 238, 256, 276 with 346

and 383 still non-operational.

17/07/44

168, 180, 199, 226, 236, 238, 256, 266, 276, 298, 339, 346, 383, 411, 428,

449.

LCM 166 missing from list. LCM 226 also shown present although believed lost

on July 21st.

24/07/44

166, 168, 180, 199, 226, 236, 238, 266, 276, 298, 339, 346, 383, 411, 449,

LCM(3) 502 and 511.

LCM 226 still recorded present.

31/07/44

199, 226, 266, 298, 339, 346, 383, 411, 428, 449, LCM(3) 502 and 511.

LCM 166 missing from list. Although no details are recorded against any of

the craft on July 31st still listed are LCM 226 and 346 and 383.

Mk3 LCM 650 Flotilla:

6/6/44

1100, 1164, 1197, 1212, 1213, 1214, 1215, 1216, 1234, 1235, 1236, 1240,

1241, 1242, 1277, 1278.

LCM in italics are ‘War Losses’ in Normandy.

Editorial Note; The craft of LCM Flotilla 650 of F Squadron, have been included in this account which is primarily about LCM Flotilla 601. For the

sake of accuracy, it should be noted that there is no documentary proof that 650

was involved in the same crossing of the English Channel as 601 on July 21st

1944, although the author, Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing Craft

Association, strongly suspects that they were. Furthermore, the Royal Marines lost from 650 LCM, may have been lost from various craft of

the flotilla or may have formed the crew of one of the LCMs recorded as lost.

[Photos courtesy

of Robert Guthrie. Middle front row is Tommy Langan in the late 1930s. He was a

promising football player and was capped for the Scottish Junior International

team].

[Photos courtesy

of Robert Guthrie. Middle front row is Tommy Langan in the late 1930s. He was a

promising football player and was capped for the Scottish Junior International

team].

Of those lost from 601 LCM Flotilla, only two have known marked graves - Royal Marine Corporal Thomas Langan, who rests in Dannes Cemetery and Royal

Marine Ronald Andrews, who is buried in Calais. Royal Marine Henry Diviny of 650

LCM, is interred at Boulougne Eastern Cemetery.

Reflections

Tony Chapman writes. As this account is

being written in May of 2010, I have been involved with the

veterans of the LST and Landing Craft Association for almost sixteen years. It

started just prior to the 50th Anniversary of the D-Day Landings in 1994.

Initially, I was involved in private research for a family member. That particular project kept me

engaged for a period of a year, during which time I became very involved with

veterans of this association, and indeed veterans world-wide. I

have the utmost respect and admiration for them all, and I count myself privileged to

have unlimited access to them.

This association in 1994 comprised many more veterans than it does today.

The

passage of time is taking its toll on those that remain. There is talk of the Association disbanding in 2012, if not

before. That day will be a very sad day indeed.

During the course of my early involvement with

the Association, I spoke to many veterans about their experiences during the war

years and sought details of the landing craft or ships they served on, and the

actions they were involved in during the period 1942 to 1946. Some had been at

Dieppe in August 1942 while others had gone on to serve in the Mediterranean.

Amongst them were many who had been recalled for Operation Overlord, the D-Day

landings in Normandy on June 6th 1944. For many, it was their first taste of

action, and sadly, for some, their last.

Even for survivors, the experience left an indelible mark that was impossible

to erase. Nobby Clark's

son regrets that his father did not live to read this account of the tragic fate

of the 601 LCM Flotilla. He feels that if his father had read it, many of

the ghosts that remained with him from 1944 until the day he died, would have

been laid to rest.

Many events were spoken of, but

two tragedies stand out above all others - the loss of men and craft of

the 9th LCT Flotilla off Land’s End during October 1944, now recalled on this

website under the title ‘The Lost

Flotilla’. The other, was, ofcourse, the loss of the men and craft of the Royal Marine and Royal

Navy manned 601 LCM Flotilla. Although many veterans spoke of it, very few had any

first hand knowledge of what actually took place. Many times I recall veteran

Royal Marines voicing the opinion that the 601 LCM Flotilla should never have

attempted the return journey to England given the weather at the time.

In more recent times I have felt closer to the truth,

and now, 66 years after the events described above, I've recorded

here the product of all the information I have gathered concerning the loss of the men of 601 LCM

Flotilla. Also lost on the same day were Royal Marines of the 650 LCM Flotilla.

I feel they must have been part of the same homeward bound convoy, although I'm

presently unable to confirm that from official records.

[Sadly, Tony Chapman died, suddenly, in the summer of 2013.

Although we never met, we were good friends for 10 years, as we worked together

on recording the experiences of those who served their country in landing craft

large and small in WW2. His contribution to this website was immense, indeed

unsurpassed. His friendship, expertise, helpful disposition and enthusiasm for

the subject, are sorely missed. Geoff Slee].

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on

our 'Combined Operations Books' page. They, or any

other books you know about, can be purchased on-line from the

Advanced Book Exchange (ABE). Their search banner link, on our 'Books' page, checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Just type in, or copy and paste the

title of your choice, or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Correspondence

Hi Geoff, I hope you are well. Just a quick e

mail to catch up.

We are scheduled to attend the D-Day 75

commemorations in France, taking my father, Leslie Skelton, a Royal Navy

veteran, who was an 18 year old Petty Officer aboard a requisitioned London

barge as part of the maintenance party for 601 Flotilla. I wonder if any of

your visitors to the website would know of anyone still alive who was

associated with 601? (Use Contact Us in Page Banner). We had correspondence

with Captain Martin Tyrell some years ago, now sadly departed.

I have written a brief account of my father’s

activities and I see you are inviting people to add them to your site so will

do this in the next few days.

On the eve of what is to be a very significant

and emotional experience, I would like to take the opportunity to thank you

for creating the website, fostering a community and ensuring that the memory

of 601 Flotilla is available to future generations.

With very best wishes,

Chris Skelton (5/19).

James Albert Latham.

I look on the internet from time-to-time,

seeking anything relating to my father’s wartime service, and was amazed to

find your excellent website. On the 601 LCM Flotilla page, my father was the

‘sole survivor’ referred to. His full name was James Albert Latham, known as

Jim, from Birmingham. You rightly said that Lady Luck smiled on him when he

was rescued after a night in the water, but that was not the only time. On

another occasion, he was on board a ship, playing cards, when it was sunk by

a torpedo. When he was pulled from the water he was still holding on to his

winnings!

I'll look out a photo of my

father in uniform, which I'll copy to you, together with a photo of his map

case. I wish I had found you website before his death in 2012, as your

account of the 601 LCM Flotilla, may have got him talking about his war

service, something he was never keen to do.

Many thanks to you, regards,

Royal Marine Ronald Smith. What a great website! At last I've been able to find out

what happened to my uncle, Royal Marine Ronald Smith. From the Itchenor photos you have

posted, I can see my parents. Ronald's sister Cissy (nee Smith) is still alive, the last of her generation in our family. I feel so honoured

to be part of this history. Thank you so much for covering this WW2 tragedy

and bringing it to light for future generations.

It

would be great to hear from anyone who knew or served with my uncle. Click on

the e-mail icon.

Regards

Ron English

The Sole Survivor. My father, James E

Clarke, aged 90 in 2015, was with the 601 which set off for Normandy from

Itchenor in June 1944. I read him your account and he remembered many of

the names. He spoke to the sole survivor 'Latham' who gave him this

account of what happened just 3 days after the sinking.

The craft was sinking as it took in water.

Sergeant Latham told me that a lad from Blackpool had been trying to stem

the aft leak but to no avail. Latham was soon in the water and he held on to

a nearby cork ring life preserver 'belt.' A Canadian lieutenant, possibly

Aylan-Parker, held on similarly, but sometime during the night he let

go... either because he had died or simply because he could not hold on any

longer. All the men were very sea sick to start with which was debilitating

in itself, but when coupled to the cold sea water, their energy quickly

drained away. Sergeant Latham was picked up in the early hours of the

morning after spending about five hours in the water.

Acknowledgements

Recalling the loss of the men of 601 LCM Flotilla, returning from Normandy on

July 21st 1944 by Tony Chapman, Official Archivist/Historian of the LST and

Landing Craft Association (Royal Navy). Source material was drawn from

the writings of Lieutenant (later Captain) Martin Tyrell RM MD and Corporal

George Morrison RM both of 601 LCM Flotilla

_small.jpg)