|

D Day - A Combined Operations (Royal Navy) Signaller.

A Daughter's Appreciation

Background Background

My dad, Ralph

Matthews, was from Shildon, County Durham. In early 1944, as a Senior

Yeoman of Signals in the Royal Navy, he was posted to Weymouth and

billeted in the town, having earlier been attached to Combined Operations

for what turned out to be preparations for D-Day as part of Assault Force

G - Gold Beach.

Training

There were weeks upon weeks of intensive

training based at Weymouth prior to receiving the order to assemble at

Southampton. Everyone realised the long planned for invasion was rapidly

approaching, although only a very few senior military

personnel knew when and where the

assault would take place.

[Photo;

Commandos of 47 (RM) Commando coming ashore from LCAs (Landing Craft

Assault) on Jig Green beach, Gold area, 6 June 1944. LCTs unloading

priority vehicles of 231st Brigade, 50th Division, can be seen in the

background. © IWM (B 5245)].

My dad attended lectures and meetings

about the landings and participated in countless exercises on the south coast in places

such as Hayling Island to simulate the

conditions of an actual landing.

Preparations

There were thousands of landing craft of many types dispersed in every river

estuary and port around the south of England, ready to assemble as the

largest amphibious

invasion force in history at the appointed time.

Weymouth and its surroundings had been

largely taken over by Combined Ops and, as part of

Communications/Telegraphy, my dad served on HMS Kingsmill, one of 18

Assault HQ ships. She was originally

an American ship, which, together with a couple of others, were fitted out

with state of the art radio communications equipment. Remarkably, my dad met an old boyhood friend from Shildon, Donald Bulch,

who was attached to one of these vessels, the Kingsmill being the HQ ship

for Gold Beach, while the two LCHs were the HQ vessels for the Red and

Green sectors of Gold Beach.

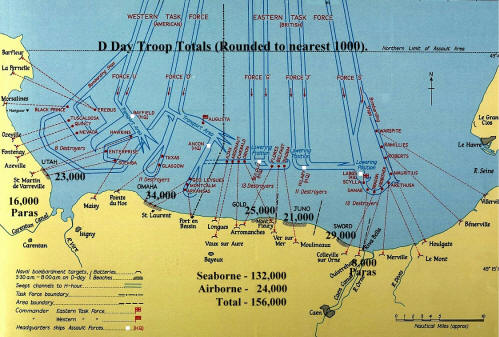

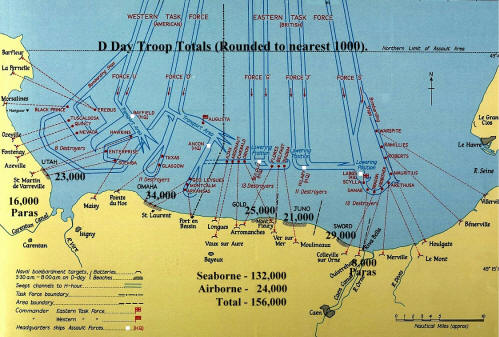

Unlike the main HQ ships highlighted in

the map below, the Assault HQ ships communicated with troops ashore, who

provided intelligence on targets and reported back on the accuracy of

shelling to allow the warships' gunners to fine tune the trajectory of

their shells. The Assault HQ ships also directed minor landing craft and

amphibian vehicles operating between the beaches and large troop and cargo transports anchored a few miles

offshore. The Assault HQ ships also had lines of

communication with the crews of fighter bombers and rocket firing aircraft

via the air force personnel aboard Kingsmill. When required for

strikes against specific ground targets impeding the progress of the

Allied troops, direct radio

contact between air crews and forward platoons and other junior commanders

was arranged.

As D Day approached, the forces were told to

consolidate their kit by placing wanted items in

store and disposing of others, since their battle kit alone would be more than

enough to carry and look after. Dad destroyed letters from my mother but kept

her photograph

and a verse copied from a poem, which we found much later in his New

Testament/Prayer Book that he took with him to Normandy.

The poem is called

The White Cliffs by Alice Duer Miller, written in 1940.

It just about breaks my heart.

Lovers in peacetime

With fifty years to live,

Have time to tease and quarrel

And question what to give;

But lovers in wartime

Better understand

The fullness of living,

With death close at hand.

As

a signalman, my dad carried the same kit as a soldier, except for the

rifle. Extra men were drafted in and troops

were moved to the Southampton area too. He was initially billeted in

tented accommodation under strict security before being moved by

lorry to board the Kingsmill. This was it, they thought, but the

invasion was delayed by a day due to bad weather.

D Day

Late at night on Monday 5 June, the Kingsmill

and the heavy landing craft dad's friend, Donald, was on made their way

into the Solent. My dad had never seen such an armada – ships of every

size and class carrying men of various nationalities with

a multitude of skills, setting off at different times throughout the night

according to the precise timetable of Operation Neptune, the amphibious phase of

Operation Overlord.

Within his range of vision, he saw many hundreds of aircraft flying overhead, fighters, troop carriers, bombers

and towed gliders carrying paratroopers and equipment or providing aerial cover and support.

As daylight dawned, ships began taking up

their final positions off the Normandy coast with the Kingsmill's two LCHs

just ahead. My dad had been on the bridge of his ship most of the

night communicating with neighbouring craft by signal lamp (Aldis

lamp) since strict radio silence was in force to ensure the German

defences remained unaware of what was to befall them in just a few hours.

The element of surprise was paramount.

Dad saw landing craft of all sizes ferrying

men and equipment ashore, while battleships and cruisers bombarded the

shore in advance of the initial assault troops landing... the enemy big

guns ashore returning fire. Enemy shells exploded on ships and landing

craft, causing death and destruction. The LCH vessel on which Donald Bulch was serving, was hit and her aerials

shot away. Donald was awarded the DSM (Distinguished Service Medal)

for quickly erecting makeshift aerials, holding them in place and helping

to re-establish communications with other vessels. The noise was

horrendous and few managed to sleep on the crossing and for many hours

afterwards. For those who survived D Day it was indeed the longest day.

Assault Force G headed for Gold Beach with HMS Kingsmill as

the flagship of section G2. Here, 30th Corps, 50th Infantry Division and

8th Armoured Brigade of the British 2nd Army landed. On Omaha the

Americans met fierce resistance and difficult terrain, which they

eventually overcame after great losses.

There was resistance to overcome on all landing beaches. On Gold itself, there

were places where a breakout allowed armour and men to move inland but

in another location a German pillbox stubbornly blocked the way. CSM Stan Hollis, a Middlesbrough man of the 50th Northumbrian

Division of the Green Howards, dealt with it almost single-handedly,

rescuing many of his men in the process. For this most courageous act, he

received the only Victoria Cross awarded on D-Day.

As the invasion developed, the Assault HQ

ships amended the overall plan in the light of operational experience on

the ground, including new targets for the 'Bombarding' warships, committing

reserve brigades earlier than planned, the provision of hot food for minor

landing craft crews (Landing Barge Kitchens) and the replacement of lost

or damaged equipment.

Beyond the initial assaults the longest

day continued as wave after wave of follow on troops, tanks, lorries,

munitions and supplies were landed but, as the longest day turned into

night, German planes were finally mobilised in significant numbers and the

beachheads were bombed.

Post D Day

My dad's initial job of communicating

with other vessels and with

the beachhead was over. He was landed on the beach in the late

afternoon/early evening to report to the Beachmaster's HQ, located on a

farm in Ver sur Mer (see map above). He was expected but wasn't really needed, so he was

dispatched to the nearby village of Meuvaines, where he was to help

establish a communications unit based in the grounds of a chateau.

However, it wasn't as luxurious as it sounds, since his accommodation was

a tent on the lawn in front of the chateau! D-Day for dad ended under

canvas in Normandy, with the sights and sounds of battle all around.

Camped in the same ground was war artist Stephen Bone.

Dad awoke on Wednesday 7 June after a

restless sleep but better than he

had managed during the previous two days. In and around Meuvaines, the

signs of the battle were evident from burned out jeeps, motorbikes,

armoured cars, tanks, lorries, demolished buildings and small craters. The

village itself comprised a church, some farms, a couple of chateaux and

rather shabby village houses. The expansive lawns at the chateaux were

already crammed full of tents and lorries, which served as Communications and Signals "offices" complete with

aerials, transmitters and mobile radio telephones. The unit was soon

routing signals amongst naval,

army and air force units, mainly by radio telephones using special

frequencies. All of this was under Combined Operations.

The more opulent chateau, which had been

used by German forces, was booby trapped, so sleeping, eating,

washing and toileting under canvas was necessary until the building had

been cleared and declared safe. Bombs were frequently dropped with deadly

shrapnel covering a wide area around the impact site. Leaping into slit

trenches, at the first hint of an air raid, became routine.

Initially, rations from the army's Detail

Issuing Depot, comprising mainly dried and tinned food that required

little cooking or even heating up, sustained them but, inevitably,

bartering with and begging from the locals and newly arrived landing craft

became the norm. Dad became quite adept in obtaining food and learned to

make the best of limited ingredients including the resurrection of stale

bread! As they became familiar faces in the local community, wine and

vegetables were regularly exchanged for chocolate and other 'goodies'

available only to servicemen. The men celebrated Bastille Day, 14 July,

1944, with the villagers, including a feast and a procession. Dad and his

comrades became renowned for their cooking, though none had any

qualifications or training. They even catered for a party of "top brass",

which dad always thought included Churchill. These important men tipped

them £5 for their trouble... amongst about 8

of them! [Churchill and his military advisers

certainly visited the Normandy beaches on D Day + 6. For more information

on this, visit

https://www.combinedops.com/Combined-Operations-Churchill-Signal-of-Gratitude.htm

On the 7th of July, the men witnessed the

overwhelming Allied fire power during the concerted attack on Caen, which

resulted in its liberation on the 9 July. Bayeaux and Rouen were also liberated. The

Mulberry Harbour off Arromanches became operational and was soon receiving

large vessels carrying men, equipment, munitions and supplies for the advancing armies. The

job of communications unit at the chateau was easing, which provided an opportunity

to sight-see in relative safety. One of the men had sufficient spare

time to build motor cycles from abandoned vehicles and to repair other

equipment.

The decision was taken to redeploy the

unit, so a

short leave back to 'Blighty' was authorised and my dad was able to see

his beloved wife for a few days. After a couple more weeks under orders

in Fareham, he returned to France as part of a special Communications

unit, which followed the army from port to port along the coast up to

Calais, via Caen, Le Havre and the Seine, establishing signal posts as

they went. The sounds of war were receding as the enemy retreated towards

their homeland, however, the physical destruction in the aftermath of

burned out vehicles and buildings was omnipresent. Dad light-heartedly

thought that each nation had its distinctive smell, which was probably not politically correct

even then. Britain smelled of milk, the USA of newspapers, comic books or

possibly money, Germany of

sauerkraut, Italy of olive oil and France of garlic. The smell common to

all, everywhere, was the pungent odour of death.

As

he moved with the Allied advance, he

stayed in German barracks, French chateaux, schools and in the lighthouse

in Calais, where he was based until the end of 1945. When there were

troops in the area, a good social and sporting life presented itself. Dad

played rugby and football against other units and services when he was

listed in the match programmes as famous footballer of the day, Stanley

Matthews. They drew the largest crowd ever known in those parts! As

he moved with the Allied advance, he

stayed in German barracks, French chateaux, schools and in the lighthouse

in Calais, where he was based until the end of 1945. When there were

troops in the area, a good social and sporting life presented itself. Dad

played rugby and football against other units and services when he was

listed in the match programmes as famous footballer of the day, Stanley

Matthews. They drew the largest crowd ever known in those parts!

As the war drew to an end, the once busy base was run down as men were

transferred to Belgium, the Netherlands and back to Britain. For a while

my dad and his lads were the only Communications unit left in Northern

France and he was promoted to Chief Yeoman of Signals, the most senior

rating in the area.

He was posted back to Fareham in November

1945 and decided to leave the Royal Navy, although they were keen for him

to become an instructor. He had joined up as a 16 year old boy to serve on

ships, not to work on shore, so he request demob. Instead they posted him

to Peterhead on the north east coast of Scotland! Hell hath no fury like

the Navy scorned!

He finally returned to civvy-street and

my mum in time for bonfire night, 1946. He looked back fondly on his time

in the navy and in particular his time in Combined Ops. He claimed he and

his lads were the most efficient, best organised and best fed unit in

France! Such was their culinary reputation that they even cooked for "top

brass"!

He was very proud to have played his part in the liberation of

Europe. He was just a Shildon lad but, like thousands and thousands of

ordinary lads from the area, he played his

part.

I am so proud of my dad, my hero.

Acknowledgements

This account of Combined Operations

(Royal Navy) signaller, Ralph Matthews was expanded and collated by Geoff

Slee from a story written by his daughter, Di Mellor, based on Ralph's

journals. It was approved by her before publication.

|