|

Operation Jubilee - The Disastrous

Dieppe Raid.

August 19, 1942.

Few raids have been subjected to so much scrutiny, analysis and comment as

Operation Jubilee, better known as the Dieppe Raid. It aimed to seize a major

port and to hold it for a short period, while seeking opportunities to gather

intelligence and to demolish

important infrastructure and buildings. The raid would show the UK's

determination to fight on and, if successful, it would boost the morale of the

armed forces and the country. Few raids have been subjected to so much scrutiny, analysis and comment as

Operation Jubilee, better known as the Dieppe Raid. It aimed to seize a major

port and to hold it for a short period, while seeking opportunities to gather

intelligence and to demolish

important infrastructure and buildings. The raid would show the UK's

determination to fight on and, if successful, it would boost the morale of the

armed forces and the country.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

At the same

time, Mountbatten wanted to test Combined Operations amphibious

landing training, equipment and techniques in a sizeable raid against entrenched German shore

defences. The raid

failed in almost every regard and at a high cost in lives lost, numbers injured

and captured, particularly for the Canadian Forces involved.

In August 2012, a 'History TV' documentary

based on 15years research by David O'Keefe provided fresh insight into other

top secret purposes behind the raid, which casts a different light on the day's

events. More details on this below. In any event, lessons were learned and similar mistakes were

avoided in future amphibious operations, including D-Day.

Background

1942

was the worst year of the war for the Allies. At the time of Operation Jubilee, the UK could not boast a single

victory against the Germans in the field (excluding Commando 'pin-prick' raids) and British and Commonwealth troops in North Africa were being

contained and driven back by the Africa Corps.

In the Far East, the

Japanese were occupying substantial parts of the former British Empire, the

Americans were still feeling their material losses at Pearl Harbour and

struggling to maintain what was left of their Philippine Army and the Russians

were under pressure as Hitler's thrust into

the Caucuses took hold. The immediate outlook was bleak.

The most critical situation

was on the Russian Front, where the German

offensive seemed unstoppable. Stalin called loudly and often for an offensive in

the west to reduce the pressure on his armies and, in truth, a Russian military collapse would be

catastrophic for the whole Allied war effort.

The Russian viewpoint

enjoyed American support, with some American military leaders

favouring action in the Pacific against the Japanese, if no large scale offensive in the

west was possible. The general public also agitated for offensive action in support

OF the beleaguered Russians. Mass rallies

were held in both Trafalgar

Square in London and Madison Square gardens in New York during April, 1942,

which

called for "a second front now!"

There was, therefore,

increasing pressure on Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff to mount a

significant offensive operation on the Western Front, that would at least discourage Hitler from sending additional reinforcements to the East

Front.

It was against this

menacing background that the Dieppe raid was planned.

Plans & Preparations

Originally

conceived in April 1942 by Combined Operations Headquarters (COHQ), and code named

'Operation Rutter', the Allies planned to conduct a major, division size, raid on

a German held port on the French channel coast and to hold it for the duration

of at least two tides. They would cause the

greatest amount of destruction of enemy facilities and defences before

withdrawing.

This

original plan was approved by the Chiefs of Staff in May 1942. It included

dropping paratroops inland of the port, prior to a frontal amphibious assault.

However, with the involvement of paratroops, the raid was vulnerable to weather conditions in the area. General Montgomery was to

supply the bulk of the troops from his South Eastern Command but the Canadian

Government pressed for Canadian troops to see some action. The Canadian 2nd

Division, under the command of

Major-General 'Ham' Roberts was, subsequently, selected for the main force. This

original plan was approved by the Chiefs of Staff in May 1942. It included

dropping paratroops inland of the port, prior to a frontal amphibious assault.

However, with the involvement of paratroops, the raid was vulnerable to weather conditions in the area. General Montgomery was to

supply the bulk of the troops from his South Eastern Command but the Canadian

Government pressed for Canadian troops to see some action. The Canadian 2nd

Division, under the command of

Major-General 'Ham' Roberts was, subsequently, selected for the main force.

[Photo; Major-General 'Ham' Roberts].

The 237 vessels, 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British

and 50 US Rangers assembled in five ports on the south coast of England between

Southampton and Newhaven. In support were 74 squadrons of aircraft, of which 60

were fighter squadrons. Early rehearsals were disastrous and, by the time

they improved, the consistently bad weather caused delay.

Montgomery felt the

security of the operation was compromised, since the troops had been briefed and

German

fighter-bombers had attacked the troopships and the supporting fleet gathered in

the Solent, causing damage to two vessels. On July 7th, the raid was postponed

and the continued unsettled weather conditions just added to the gloom as the

troops and shipping were dispersed.

Had Montgomery not been ordered to Egypt to take

command of the Eighth Army, the continued representations he never made

may have prevailed, as it was, in the weeks ahead, the plan was rejuvenated and

renamed 'Jubilee'.

Although

the original planning had been undertaken by COHQ, an inter-service committee

representing Air, Army and Naval forces contrived to make the operation less

weather dependant by replacing the paratroops with seaborne troops from No 3 and

4 Army Commandos. They also reduced the scale of the planned air bombardment to

minimise the risk of French casualties but, to compensate, provided 8 destroyers

to bombard the shore. There would be 27 Churchill tanks in

support of the main infantry assault. The final plan, accepted by all 3 services

and the Chiefs of Staff, envisaged assault landings at eight separate locations

in the vicinity of Dieppe. The Royal Marine Commando were to land in fast motor

launches after the main landing to destroy the dock and recover documents

thought to be held in a port office.

A raid of this size

involving over 200 vessels, 6000 troops and 3000 naval personnel would allow the

Allies to evaluate the effectiveness of their training, equipment,

communications and strategies. This

amphibious assault landing on a defended coast would be the first undertaken by

the British since

Gallipoli 26 years earlier. There had been changes too in the capability of the

defenders, so it seemed prudent to reflect on the experience of a raid this size

before embarking upon the largest amphibious invasion force in human history,

with consequences to match.

Although they didn't know it at the time, their

intelligence on the enemy forces and the local topography was patchy. The cave-like gun positions in the cliffs on both sides of the main landing beaches were not recognised

on Allied air reconnaissance photographs and the suitability of the beaches in

terms of gradient, surface and sub surface for heavy tanks was assessed by

examining holiday snapshots and postcards. Furthermore, the

Germans were aware of Allied interest in Dieppe, because of increased radio chatter, the

concentration of landing craft and their own spy networks.

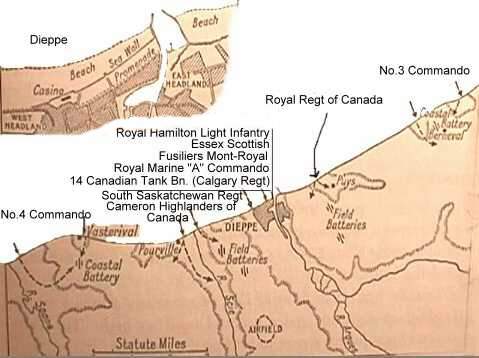

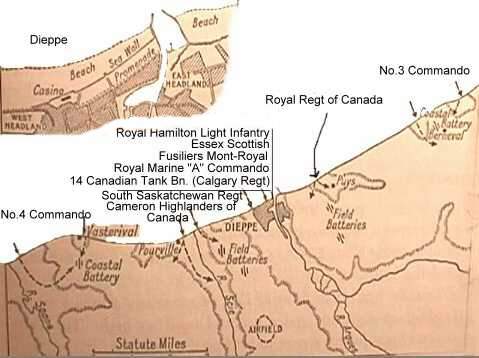

Commando

forces were to land in pre-dawn darkness; No 3 Commando approximately eight miles east of Dieppe to silence the coastal battery near Berneval,

No 4 Commando and 50 US Rangers to neutralize the coastal battery near Varengeville,

six miles west of Dieppe. In

both cases they would make two landings to effect a pincer movement on the

batteries, which each had a cadre of over a hundred. Both of these gun

positions could easily range on assault ships positioned off Dieppe, so

their neutralisation was important. Commando

forces were to land in pre-dawn darkness; No 3 Commando approximately eight miles east of Dieppe to silence the coastal battery near Berneval,

No 4 Commando and 50 US Rangers to neutralize the coastal battery near Varengeville,

six miles west of Dieppe. In

both cases they would make two landings to effect a pincer movement on the

batteries, which each had a cadre of over a hundred. Both of these gun

positions could easily range on assault ships positioned off Dieppe, so

their neutralisation was important.

An assault

force (see map for composition) would land at four separate locations, immediately to the east of Dieppe at Puys and immediately west at Pourville,

half an hour before the main assault. Their objective was to disable the

guns and machine gun nests on the cliffs that covered the main landing

beaches east and west of the town.

The main assaults on

two beaches in front of the town were scheduled for the early daylight

hours - essentially a frontal assault.

Dieppe was not thought to be heavily defended and with tank support in the

front line, it was anticipated that this force would be sufficient to accomplish the raid's

objectives.

The

Raid

Operation

Jubilee commenced in the late evening hours of August 18th, 1942. It was a

warm, moonless night as the fleet of vessels headed across the channel. Operation

Jubilee commenced in the late evening hours of August 18th, 1942. It was a

warm, moonless night as the fleet of vessels headed across the channel.

[Photo; Light naval craft covering the landing

during the Combined Operations daylight raid on Dieppe. MGB 321 is nearest

the camera (partly obscured by some sailors in the foreground) whilst

submarine chaser Q 014 can be seen in the middle distance. © IWM (A

11234)].

The presence of a German convoy proceeding to Dieppe from Boulogne had been picked up by Radar stations on the English coast.

Twice, at 1.30 am and

again at 2.30 am on August 19th, they radioed warnings to the naval commander

Captain Hughes-Hallet. These warnings were not acknowledged and the raiding

force took no evasive action.

The main assault troops were convoyed in

large mother ships, with their LCPs (Landing Craft Personnel) hanging from davits

ready to be lowered into the water a few miles off shore. Most of the

Commandos travelled independently in their own LCPs which held about 20 men

each, while LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) transported the tanks. The main assault troops were convoyed in

large mother ships, with their LCPs (Landing Craft Personnel) hanging from davits

ready to be lowered into the water a few miles off shore. Most of the

Commandos travelled independently in their own LCPs which held about 20 men

each, while LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) transported the tanks.

On passage to

Yellow Beach (Berneval), 3 Commando Group comprised twentyfour LCP(L)s escorted

by one LCF(L), ML 346 and SGB 305. At 03.30hrs, German convoy No. 2437,

comprising five Dutch coastal motor sailing vessels (FRANZ, HYDRA, IRIS,

OSTFLANDREN and SPES), en route to Dieppe from Boulogne, escorted by

anti-submarine chasers UJs 1411, 1404 and minesweeper M 4015, where sighted.

Several vessels in front of them fired star-shells, which lit up the Group 5

vessels carrying 3 Commando. At 03.47hrs, the opposing escort forces opened fire

and during the battle the other vessels from both sides scattered, during which

LCP(L)s 081 and 157 were lost and SGB 308 was immobilised and guns disabled. 40%

of the crew were wounded.

ML346 tried to

close on SGB 308 but was driven back by enemy gunfire. LCF(L) 1, which was armed

with two 4" Mk V guns and three 20mm Oerlikon cannons, concentrated its gunfire

on UJ 1404. It was soon ablaze, steering damaged and guns silenced.

Subsequently, ML 346 & LCF(L) 1 combined to drive off the German boats, but not

before they reported to Army Group D on the landing craft then three miles from

Dieppe. Whilst the gun battle ensued, the destroyers HMS BROCKESBY and ORP

SLAZAK, which had noticed the engagement, did not intervene in the skirmish

because their commanders incorrectly assumed that the landing craft had come

under fire from the shore batteries.

Only 18 Commandos

landed on time at their planned landing points, which removed any prospect

of an all out attack. They resorted to sniping, which proved quite

effective in keeping the German gunners occupied but they were eventually

forced to withdraw in the face of superior German forces. The battery was

sufficiently restrained that, as far as is known, no vessel was sunk by

its gunfire.

No

4 Commando executed an almost flawless operation and, in hard fighting, they

overran and neutralized the coastal battery on the western flank. Commando Captain Pat Porteous

was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in this hard fought battle.

At Puy, the Royal Regiment of Canada

suffered grievous losses, when only 60 out of 543 men were recovered from

the beach and to the west of Dieppe, only a few men from the South

Saskatchewan Regiment reached their objective. The Queen's Own Cameron

Highlanders of Canada penetrated the furthest inland but were forced back

with the arrival of German reinforcements.

The

main assault landings by the Essex Scottish Regiment and the Royal

Hamilton Light Infantry immediately encountered

fierce opposition from an alerted and prepared

enemy. The original heavy air bombing attack had been removed from the plan and

a protective smoke screen was blown clear of the beach by

a southerly breeze. Nine tanks scheduled to land with the first infantry assault

were late due to navigational errors and when tanks did land many lost their

tracks, as they bogged down in the deep shingle, leaving them vulnerable to

anti-tank fire. Thirteen tanks left the beach area but were stopped by

concrete road blocks and did not reach the town.

Intelligence gathering had failed to

identify numerous gun and machine gun positions in caves dug into the high cliffs overlooking the landing beaches or that the port was strongly defended by experienced German troops.

The supporting bombardment by

destroyers and a low level strafing attack by 5 squadrons of

Hurricanes did not suppress the German

defences. Commander Harry Leslie, RNVR recalled the failure of the support ships

to depress their guns sufficiently to hit the German positions at either end of

the bay. His flotilla of MLs supported the landing craft and for his part in towing damaged LVPs offshore

to safety in very hazardous conditions, he was awarded the DSC. The supporting bombardment by

destroyers and a low level strafing attack by 5 squadrons of

Hurricanes did not suppress the German

defences. Commander Harry Leslie, RNVR recalled the failure of the support ships

to depress their guns sufficiently to hit the German positions at either end of

the bay. His flotilla of MLs supported the landing craft and for his part in towing damaged LVPs offshore

to safety in very hazardous conditions, he was awarded the DSC.

[Photo; left - Cameron Highlanders of

Canada].

All these factors contributed to the mowing down of the initial assault of

infantry and engineers. Without covering fire, the enfilading fire onto

the landing beaches was unrestricted. Subsequent assault waves piled into

the first and were subjected to similar treatment.

A few groups of

Canadian infantry broke into the town but only confused and misleading

reports reached the force commander, Major-General Roberts, aboard his

headquarters ship. It was some time before the commanders afloat realised

the disastrous situation on the beaches, unfortunately only after the

floating reserve had been sent into the carnage. At 9.40 am, the signal to

withdraw " Vanquish 1100 hours" was sent to all the assault forces. The

evacuation of the surviving troops added many more casualties amongst the

naval officers and ratings manning the landing craft and the

troops trying to reach them.

The

Outcome

Almost 4,000

Canadian and British had been killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The Canadians

lost two thirds of their force, with 907 dead or later to die from their wounds. Major-General

Roberts unfairly became the official scapegoat and was never to command troops

in the field again. Almost 4,000

Canadian and British had been killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The Canadians

lost two thirds of their force, with 907 dead or later to die from their wounds. Major-General

Roberts unfairly became the official scapegoat and was never to command troops

in the field again.

[Photo; Some of the Canadian troops resting on board a

destroyer after the Combined Operations daylight raid on Dieppe. The strain of

the operation can be seen on their faces. © IWM (A 11218)].

Year after year, on August

19th, a small box arrived in the post for him. Its contents, a small piece of

stale cake - a cruel reminder of his attempt to boost morale at the pre-raid

briefing "Don't worry boys. It will be a piece of cake!"

What went wrong?

-

there were few less suited locations on the French coast for an assault landing. The tall cliffs in the area of the main landing

beaches were perfect for

enfilade fire on the assault troops and the deep beach shale was

absolutely unsuited to heavy vehicles including tanks.

-

the intelligence

available was inaccurate incomplete and misleading. The information on

the German defences, troop levels and beach conditions was hopelessly

out of date. It's been suggested that more up to date information on

some aspects was available through ULTRA (the top

secret breaking of the German Enigma codes) but was never asked for or

passed on.

-

the

assault was viable only when certain conditions of time and tide

prevailed. These conditions (high tide at or near dawn) were as well

known to the German forces as they were to the British planners. It

was not surprising, that during these periods of potential threat,

German forces would be on heightened alert. Despite this, the plan

depended on tactical surprise. Was it an error to believe that the

Germans were unaware of these factors?

-

post

war post-mortems have often focused on the changes to the original

plan in general and the withdrawal of the bombing force in particular.

It's arguable that these changes by themselves were not the

overwhelming decisive factor. Bombing was not a precision tool at the

time of Dieppe, when pin point accuracy was needed to keep German

defenders running for cover. It's conceivable therefore that a much

heavier weight of offshore bombardment was needed than was provided.

If heavier capital ships had been present, they could have kept the

defenders heads down until the troops were within a few metres of the

beach.

-

the

plan was heavily dependent on the critical timing of its various

components - there was little or no room for error or delay anywhere

without adverse knock-on consequences. The effect of this weakness was

compounded by poor communications, which failed to update senior

officers of progress in time to take appropriate remedial action.

Lessons

Learned

The

capture of a usable port early in any large scale invasion

of enemy occupied territory was ideal for the immense

logistics involved in keeping the supply chain open.

However, such an objective was fraught with difficulties, hence the

long held emphasis on landing directly on to unimproved

landing beaches. The experience of

Dieppe reinforced the wisdom of this view and it became the

inspiration behind the development of

Mulberry Harbours and

the Pipe Line Under the Ocean

(PLUTO) and many other special initiatives that

contributed to the success of subsequent major landings in

North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, Southern France and

Walcheren. The

capture of a usable port early in any large scale invasion

of enemy occupied territory was ideal for the immense

logistics involved in keeping the supply chain open.

However, such an objective was fraught with difficulties, hence the

long held emphasis on landing directly on to unimproved

landing beaches. The experience of

Dieppe reinforced the wisdom of this view and it became the

inspiration behind the development of

Mulberry Harbours and

the Pipe Line Under the Ocean

(PLUTO) and many other special initiatives that

contributed to the success of subsequent major landings in

North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, Southern France and

Walcheren.

[Photo; German soldiers

inspect the wreckage on the landing beach].

The need for

reliable intelligence on the strength and disposition of the

defending forces and the topography on and around the

landing beaches was clearly paramount. Lt Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Willmott,

RN, who had undertaken beach reconnaissance trials in the

Mediterranean, was recalled to the UK in the summer of 1942

to set up training programmes for the

Combined Operations Pilotage Parties

(COPPs). Beach reconnaissance became an integral part

of

the planning process for the

invasion of North Africa

in early November 1942 and in all future major landings.

Consideration of the

supporting role of vessels at sea produced numerous landing

craft adaptations such as:

Landing Craft Gun LCG, described by the BBC on

D-Day as 'mini battleships', with their 4.7 inch guns and

other armaments operating inshore; Landing

Craft Flack, LCF, to provide anti-aircraft cover

over the landing area;

Landing Craft

Tank (Rocket), LCT (R), for the initial bombardment of

the beaches in advance

of troops landing and Landing Craft Assault (Hedgerow), LCA

(HR), that could lob volleys of spigot bombs onto the beach

area, primarily to detonate hidden enemy mines.

The need for troop commanders

afloat to be aware of the on-going progress of the invading

force was essential for well considered and justifiable

decisions on, for example, the commitment of reserves or a

timely and well organised strategic withdrawal.

The need

for landing craft

to be armoured against small arms fire was now considered an

imperative to reduce casualties on the approaches to the landing

beaches.

to reduce casualties on the approaches to the landing

beaches.

[Photo; Canadian POWs in Dieppe. In the middle/left of the photo is John Machuk

of the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Winnipeg giving a

wounded soldier the support of his arm].

Who knows how

many lives were saved in later amphibious landings, particularly Normandy, as a

result of the casualties at Dieppe? This failed assault had ramifications for

the German forces too. Their confidence grew in their ability to withstand an

invading force and they came to believe that the inevitable Allied invasion

would include an area with good port facilities. They subsequently concentrated

on providing stronger defences around the main ports to the detriment of open

beach locations.

In this context, Albert Speer, former Nazi minister of armaments, admitted

at the Nuremberg trials that the Germans' costly, two-year effort to

construct Atlantic defences had been 'brought to nothing because of an

idea of simple genius' - the Mulberry Harbours.

The Dieppe raid carried

with it a high cost but the lessons learned inspired and accelerated many

initiatives that contributed to the success of subsequent landings.

Sketches by

B J Mullen of 4 Commando courtesy of Frank Sidebottom. His late father in

law, Ben Clifton, served alongside the artist. Left to Right; Zero Hour, Through

the German Minefield, Withdraw from Beach, Rescue of US Airman in Channel and

Ben Clifton of 4 Commando, Ex York & Lancaster Regiment.

The outcome would almost certainly have been very different had General Roberts'

resources included those the Dieppe experience may have encouraged to be

developed, particularly the LCT(R) and the LCG.

A

Veteran Recalls

%20Les%20Ellis%202003.jpg) At a ceremony held in November 2003

to award Corporal Leslie Ellis a commemorative Dieppe medallion for his

part in the Dieppe raid, he recalled that he landed with the Royals at Puys...

"some say it was a dress rehearsal for the invasion (of Normandy) and some say

it was a whim of the top echelon. History says the Germans were waiting for us

and we didn't have a chance after that. We were all well-trained, we did what we

were trained to do. We were proud to have done it, we were soldiers ... we did

what we were expected to do." At a ceremony held in November 2003

to award Corporal Leslie Ellis a commemorative Dieppe medallion for his

part in the Dieppe raid, he recalled that he landed with the Royals at Puys...

"some say it was a dress rehearsal for the invasion (of Normandy) and some say

it was a whim of the top echelon. History says the Germans were waiting for us

and we didn't have a chance after that. We were all well-trained, we did what we

were trained to do. We were proud to have done it, we were soldiers ... we did

what we were expected to do."

The impact of that major battle may

still be debated but what remains certain is that the Canadian soldiers were

brave and there was "a feeling of pride" to serve with them. "They were a great

bunch of people. I was fortunate that I got over the (beach) wall and got back

with a few injuries and the Good Lord spared me. It all happened so fast." He

had made it behind enemy lines but as the power of the German ambush became

clear Canadian soldiers were forced to retreat.

When Ellis ran back to shore, he found

the landing craft already weighed down with injured soldiers and he knew that if

he stayed at Dieppe he would either die from enemy fire or be taken prisoner of

war. So he decided to swim in the hope that he might be rescued. "There was no

sense for me to get on that boat, so I took off my clothes and swam. I was

heading for England!" A soldier in a row-boat finally found him but he doesn't

remember being pulled out of the water. "I woke up in an anti-aircraft naval

boat." he recalled.

Ellis received the DCM (Distinguished

Conduct Medal) for his bravery. His citation as printed in The London Gazette of

October 2, 1942, read

The NCO landed with the first wave

at Puys, during the operation in the Dieppe 19 Aug 42. After a gap was blown in

the wire on the sea-wall, L/Cpl Ellis passed through the gap and proceeded up

the hill to the right; He immobilized booby traps, explored a recently abandoned

enemy post, and arriving at the top, engaged an enemy post east of the beach.

Finding himself alone, and seeing the second wave coming in, he returned to the

wall to guide them forward. Coming across a comrade paralyzed in both legs he

dragged him nearly back to the wall. Here the wounded man was killed and L/Cpl

Ellis himself wounded. He succeeded in crossing the wall and was evacuated as a casualty. L/Cpl Ellis in this action

displayed the greatest initiative, skill and devotion to duty.

Medals

Canadian Award.

The Dieppe Bar is awarded to those who participated in the Dieppe Raid on

August 19, 1942, and is worn on the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal ribbon.

A silver bar, to be attached to

the ribbon of the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal (CVSM), has been designed

featuring the word DIEPPE in raised letters on a pebbled background. Above

this, the bar bears an anchor surmounted by an eagle and a Thompson

sub-machine gun. The design was created in consultation with the Dieppe

Veterans and Prisoners of War Association.

Further Reading

There are around 300 books listed on

our 'Combined Operations Books' page. They, or any

other books you know about, can be purchased on-line from the

Advanced Book Exchange (ABE). Their search banner link, on our 'Books' page, checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Just type in, or copy and paste the

title of your choice, or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Considering the loss of life at Dieppe there was little good came of it except

lessons learned. However so successful was the raid by No 4 Commando that a

training manual, based upon their experiences, was published for the benefit of

future operations.

Vindication of ‘Ham’ Roberts? Under

General John Hamilton ‘Ham’ Roberts' watch, nearly 1,000 men died in just six

hours. He lived out his days in the Channel Islands and never sought to justify

his decisions or otherwise to defend himself. "But there's more to the story as

we learn about that ultra-secret raid" writes historian and author David

O’Keefe, "and it suggests that he was made a scapegoat." Read this well written

and plausible new

perspective on Operation Jubilee.

Watch Michael

Moore's musical tribute to the 6000 men who took part in the raid.

The Commandos at Dieppe: Rehearsal

for D Day by Will Fowler. Published by Harper Collins 2000. ISBN 0 00

711125 8. Detailed account of the successful destruction of the Hess Battery by

No 4 Commando commanded by Lord Lovat.

Dieppe:

Tragedy to Triumph, Brigadier General Denis Whitaker and Shelagh Whitaker,

1992, ISBN 0-07-551385-4 (Denis Whitaker was an infantry captain who landed on

the main beaches at Dieppe. One of the most authoritative books on the subject).

Dieppe, the

Shame and the Glory by Terence Robertson published by Pan 1965. 500 pages.

Dieppe

Revisited - a Documentary Investigation by John P Campbell. Published by

Frank Cass & Co Ltd.,1993. ISBN 0 71 463496 4.

Dieppe

(through the lens of the German war photographer) by Hugh Henry. Published

by Battle of Britain Prints International Ltd. ISBN 0 90 09176 2.

Mountbatten

and the Dieppe Raid by Brian Loring Villa. Published by Oxford University

Press 1994. ISBN 0 19 541061 0.

Clash by

Night by Derek Mills-Roberts. Published by William Kimber, London 1957.

Storm from

the Sea by Peter Young. Published by William Kimber, London 1959.

Rendezvous

at Dieppe by Earnest Langford. Published by Harbour, Madeira Park, BC 1992.

Dieppe at

Dawn by R W Thomson. Published by Hutchinson, London 1956.

The Price

of Victory by R W Thomson. Published by Constable, London 1960.

Raiders

from the Sea by Contre-Amiral Lepotier. Published by William Kimber, London

1954.

Dieppe 1942

- The Jubilee Disaster by Ronald Atkin. Published by MacMillan, London 1980.

Dress

Rehearsal - The Story of Dieppe by Quentin Reynolds. Published by Random

House, New York 1942.

We Led the

Way: Darby's Rangers by William O Darby. Published by Presidio Press 1980.

Dieppe: the

Dawn of Decision by Jacques Mordal, Paris, France 1962. English translation

by Souvenir Press, London 1963. (Authentic account drawing on many German and

French documents.)

DIEPPE:

August 19 by Eric Maguire. Published by Jonathon Cape, London, 1963

Destined to Survive: A Dieppe Veteran's Story by Jack A Poolton.

Dundurn Press, Toronto, 1998. 7¾" - 9¾". Personal reminiscences of a

Canadian Soldier taken prisoner at Dieppe in World War II. 144pp, photo

illustrated. ISBN:

155002311X /

1-55002-311-X)

Hard Tears & Soft Laughter

by James W Lauder.

When the last ships left the beaches of Dieppe on the 19th of August, 1942, more

than 2700 dead and wounded were left behind. 1,949 Canadians were captured. Of

these, 586 were wounded, and all spent the remainder of the war as prisoners of

war. Approximately 180 of the injured survivors were sent to the POW hospital in

the village of Obermassfeld, Thuringen, Germany. James William Lauder, of the

Canadian Essex Scottish Regiment, was one of those men. He was twenty-four years

old. “Hard Tears and Soft Laughter” is his story.

Correspondence

Enigma, the

encounter with German/Dutch Convoy 2437 by Group 5 (3 and 10 Commandos) and the

loss of LCP(L)s 081 and 157 - an appeal for information

My father, Waterman

II/Sgt Len Cater (RASC), skippered a small boat at Dieppe. He sometimes

reminisced about his comrades, even crying when hearing the tune ‘Die Tannenbaum’

(a.k.a. The Red Flag) which he said ‘poor old Fritz’, a German-speaking friend

of his, whistled on their way across the Channel. Their boat was sunk. Len was

rescued after several hours, but he never heard of any of the others on board

again. He died in 1980, an embittered man but father of four, of collapsed lungs

following decades fighting chronic bronchule asthma brought on by his injuries.

I’ve often wondered

if any of his comrades survived. Enquiries at the National Archive and the

Allied Special Forces Memorial Grove (where Len and his comrades are

commemorated in Memorial 20, Garden 2, beside the Dieppe Raid Memorial) have

suggested that ‘Fritz’ might have been a member of 10 Commando, and their boat

might have been sunk out in the Channel rather than inshore (where rescue hours

later might have been prevented by the shore batteries). In this case, it seems

likely they were with Group 5, the flotilla of LCP(L)s, gun boats and other

vessels taking 3 Commando in to land at Berneval. I have seen the loss of two

small boats (LCP(L)s 081 and 157) mentioned on this page (but nowhere else so

far!) and I have read an account of the action by the German POWs rescued from

one of the German convoy’s escorts (UJ1404), who claimed to have ‘sunk one or

two small boats at a range of a mile” with their 88mm gun.

Len Cater, as an

NCO, is not named in any of the RASC War Diaries (he was with 247 Company in the

Mediterranean after leaving hospital in January 1943) and is mentioned by name

only once in archives I have seen, when the CO of 247 Coy requested his return

to the RASC as soon as he was released from 99 General Hospital in Woolwich.

Like most of his generation, he said little about his role in WW2 and almost

nothing about Dieppe.

I would like to

trace who was in those LCP(L)s – Len? – and if possible who ‘Fritz’ actually

was. Perhaps he was a German-speaking member of the French 10 Commando personnel

attached to 3 Commando, or an ethnic German with X Troop – the latter seems

unlikely, as none were officially attached to 3 Commando. In any case, Len seems

to have trained with ‘Fritz’ for long enough for a strong friendship to form

between them. I hope it might be possible to inform any descendants of Fritz or

the others about the Memorial to their forebears, which can now be seen at ASFMG

in the National Arboretum.

This is made more

difficult by the fact that only the dead or missing are listed on the official

‘Roll of Honour’ – presumably listed so their officers could write to

next-of-kin afterwards. Survivors, such as Len, were not listed. The lack of

likely ‘Fritz’ candidates on the lists suggests he may have survived. There is a

second RASC NCO (Cpl Thomas Gerrard) listed as killed on the way to Berneval

with 3Cdo, but I’m not sure if he was skipper of the other LCP(L). Enquiries at

the National Archive are hampered by continuing secrecy around Dieppe in general

and Enigma-related ‘pinch’ operations in particular – as the clash with the

convoy in the Channel may have been.

If

anybody has information or possible sources of information, please contact me

through the email button link opposite.

Thank you and best

wishes,

John Cater

'Operation Jubilee – Royal Navy

Landing Craft Crews

Dear Geoff,

I'm a historian looking for any information about the early days of Combined

Operations in 1941-42. I'm interested in hearing from veterans, their families

and friends or anyone with knowledge about the men who crewed landing craft

during the Dieppe Raid. I'm also interested in the experiences of sick berth

attendants, gunners and Royal Marines involved in the landings on 19 August

1942.

If

you have any memories, diaries, ship's logs, documents, letters, stories, names,

photographs or information about Royal Naval personnel training with Landing

Craft generally and those involved in Operation Jubilee in particular, I'd love

to hear from you. No information is too little or inconsequential. Clíck on the e-mail icon opposite to reply.

Many

thanks in anticipation. Many

thanks in anticipation.

Phil Mills

The Enigma Connection.

One of Churchill's greatest concerns during the war was the

submarine menace particularly in the Atlantic. It had the potential to bring

the UK to its knees, as merchant ships carrying vital war supplies and food

were sunk. However, the British ability to decipher the enemy's "enigma"

encoded radio transmissions gave the Allies a considerable advantage in the

battle of the Atlantic.

In early 1942 this advantage was lost when the Germans

changed from a 3 "rotor" system in their "Enigma" encoders to a 4 rotor

system. Not surprisingly, Allied shipping losses increased dramatically and

were fast approaching the tipping point, where they would exceed the capacity

to replace them. It was, therefore, an imperative to crack the new encoding

machines, since failure to do so could quite possibly lose the war. British

Intelligence was desperate to get their hands on any encoding material,

particularly those concerning enemy naval traffic.

Against this background, the History TV channel documentary

"Dieppe Uncovered" (Aug 2012) puts forward the proposal that the Dieppe raid

was a "pinch" operation i.e the whole purpose of the operation was to steal or

"pinch" the latest code books and machines from the German Naval HQ in Dieppe

or German ships in Dieppe harbour. It further maintains that Mountbatten was

persuaded by Ian Fleming (James Bond author) who, at that time, was directly

under the Chief of British Naval Intelligence.

On Fleming's suggestion, a small "Commando" unit, AU 30

(assault unit 30), comprising a few select Commandos dedicated to looting any

secret material found on raids, was formed in April 1942. A surviving member

of this unit recalled that their orders were to attack the German Naval HQ in

Dieppe and, in his words, to "kill Germans". The lieutenant in charge on the

day had the street address of the German Naval HQ with orders to remove any

secret material and to deliver it to Commander Ian Fleming, who would be

waiting offshore during the raid.

AU30 was temporarily attached to the Royal Marine

Commandos on

board "The Locust" as they attempted to enter the harbour. However, they were

driven off by heavy defensive fire, so transferred to small boats for a second

attempt to land on a nearby beach. Once again they were beaten back.

Of the outcome of this raid there is no doubt, but the big

question the documentary raises is whether or not Operation Jubilee was a

cover for the "pinch" operation described above or was it just an adjunct to

the raid? The documentary's explanation of the attack plan on the town and

harbour can certainly be viewed as being in support of the "pinch" while other

more conventional reasons were simply promulgated to disguise this fact and to

deceive the enemy.

The possibility that the Canadian sacrifices had

a nobler justification than the "whim" of senior commanding officers may

provide some small comfort for the veterans and their families.

George H Pitt

Acknowledgments

Operation Jubilee, the raid on Dieppe was

substantially based on the work of

George H Pitt of Canada with the addition of

photographs and comment by Geoff Slee. Operation Jubilee, the raid on Dieppe was

substantially based on the work of

George H Pitt of Canada with the addition of

photographs and comment by Geoff Slee.

|

%20Les%20Ellis%202003.jpg)