|

Landing Craft Flak 7 - LCF 7.

Anti Aircraft Cover for Landing Craft

on Operations

Troop

and vehicle carrying landing craft were ill equipped to defend themselves

against enemy air attacks, so a number of Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) were

converted into LCFs to provide the cover they needed

and, being flat bottomed, they could operate close inshore. They were

armed with 8 Oerlikons and 4 pom-pom rapid fire

anti-aircraft guns. Troop

and vehicle carrying landing craft were ill equipped to defend themselves

against enemy air attacks, so a number of Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) were

converted into LCFs to provide the cover they needed

and, being flat bottomed, they could operate close inshore. They were

armed with 8 Oerlikons and 4 pom-pom rapid fire

anti-aircraft guns.

[Photo;

sister ship LCF 2].

These are the

recollections of a Royal Marine K

White, whose LCF took part in landings in North Africa, Pantellaria,

Sicily and Italy.

The Early Days

It was early January,

1943, when trucks dropped us off at Victoria Dock in

the East End of London. We were forty odd Royal Marines fresh out of finishing

school; the Marshal Sault (seamanship) and the Dome, Eastney (anti-aircraft

gunnery). Our first ship awaited us, a grey steel shoe box known as His

Majesty's Landing Craft Flak

7, LCF 7. It was bristling with guns with which we

were already familiar.

Royal Navy crew were

aboard two or three days before us, including the

Captain, Jimmy the One (2nd in Command), Petty Officer, Coxswain, ERA (Engine

Room Artificer), bunting tosser (Signalman), Ordnance Artificer, sick bay tiffy

and several able seamen. Two RM officers had also joined, one the OC (Officer

Commanding). The coxswain, our sergeant major, a time server and another

sergeant had a separate mess adjoining the quarters of the other ranks and

ratings. We enjoyed neither natural light nor heating.

We were organised into port and starboard

watches, four hours on duty and four off. The constant drip of condensation from

a badly corked deck in our sleeping area was akin to Chinese torture! On the

credit side, the traditional tot of rum at 11.00 hrs

every morning boosted our spirits. The greatest novelty came when the SBA (sick

bay attendant) announced the issue of free 'French letters' to all libertymen

(those granted shore leave). The first recipients went ashore like a band of

gigolos into the killing fields of East Ham. They all dribbled back up the

gangplank sadly frustrated and still virgins.

Alas, it was not long before real trouble

visited us in the shape of the Senior RM officer, who was proving to be a

martinet in the Captain Bligh mould. From the outset,

he was hell-bent on running a harsh regime and really upset the applecart by

imposing the silliest of orders, including banning

whistling on the upper deck. Several charges were served and life on board, even

before we sailed, became unbearable to all ranks, including the senior NCOs. The

sergeant major was aware of the simmering situation and openly empathized. He

suggested that each man submit a request for a transfer and the resultant wad of

chitties did the trick. A replacement CO, a gentleman this time, joined us a day

or two later.

We now settled down as a chummy ship, fully familiar with naval routine and

were allotted our action stations. We cast off and went down river, ready

for war; well not quite since there was no ammunition in the magazine! How long

would it be, I wondered,

before we chanted the ditty

'Roll on the Nelson, Rodney, Renown, This flat

bottomed bastard is getting me down.'

Our first port of call was Gravesend,

where we took on supplies and then on to Queenboro'

Dock, Sheerness to pick up the 'fireworks.' All day was spent humping cases of

20mm and 40mm shells inboard, where each individual

round had to be greased by hand. It was back breaking - the hardest day's work

of my life. Now fully 'battle worthy' we formed up in convoy in the estuary and

braced ourselves for choppy waters in the open sea. As the weather worsened,

most of us were seasick and became incapable of manning the guns. It was a dire

situation, which drove our veteran sergeant major

berserk and almost tongue-tied with invective.

Full of shame, we

entered Portsmouth harbour to recover but the only harm was to our injured

pride! For a day or two we acted as duty guard ship in the Solent. We then

sailed along the coast at Saltash, where we took on

board an extra naval officer and a navigator. We knew then that a long trip was

ahead and we soon slipped the buoy and proceeded down

the River Tamar. It was the 2nd of April, 1943.

We

Put to Sea

We tested all the guns with a burst of fire as

we proceeded west into the Atlantic. We anticipated house-high waves but this

'guinea pig' voyage of ten days was relatively benign. Gone was the earlier

unease we felt about the slap and shudder of head on waves impacting on the flat

bow. However, the seaworthiness of the vessel still gave rise to some concern as

the deck visibly flexed in the high seas!

We were in the company of about ten landing

craft shepherded by a sloop boasting something like a 3-inch gun as its main

armament. Still in ignorance of our final destination,

the group made seemingly casual progress due west for the first three days. With

the watery sun on our port beam for so long, some

speculated that we were making for Norfolk, Virginia!

It was difficult for the officer on the bridge

to keep station during the dark nights without the benefit of guiding lights and

at dawn the group was invariably scattered far and wide. We turned onto a

southerly course and shortly afterwards had our first alert... 'aircraft on the

starboard beam' followed by the 'action stations' alarm bell. Far away, out of

range, was a giant Fokker-Wulf Condor reconnaissance plane. It stalked us for

two days but, to our amazement and relief,

there was no follow up attack.

The Captain decided that there would be two

wardroom attendants (WRAs) so, accordingly,

one from each watch was pressed into volunteering. The job was not too menial

and considered by some to be a 'square number' in the warmth of the pantry,

while the others were totally exposed up top to all weathers for four hours at a

time. The cooks, in their pokey galley aft, did a good

job with the resources provided - no fridge/freezers then! The menus were

restricted to what was readily available in wartime. Bread supplies ran out soon

after leaving Cornwall and were replaced by hard tack (like big dog biscuits).

For the rest, it was dried potato, powdered egg, soya

links (sausages), tinned tomato (red lead), seedless jam, prunes, ground rice,

margarine and tea with carnation milk. All meals, hot and otherwise, had to be

carried along the upper deck and down the hatchway to the mess deck.

Once we had reached warmer waters,

we shed our heavy clothing in favour of khaki drill gear. The Strait of

Gibraltar was a welcome sight. Tarifa, where the word tariff originated, was on

the left bank and in the far distant right was Tangiers.

The

Mediterranean The

Mediterranean

[Map courtesy of Google data.

2017].

The Rock of Gibraltar loomed large, overlooking an anchorage sheltering myriad

ships, many no doubt having participated in the recent Operation Torch landings.

Shore leave was restricted while supplies, fuel and drinking water were taken on

board. We were due back pay of about twelve bob (60p) a week,

which was enough to purchase fags (cigarettes) going by the exotic names of

Passing Cloud, Three Castles or Lucky Strike. A bag of letters to parents,

sweethearts and wives was consigned to the Fleet Post Office and we cast off.

Gibralter was ablaze with bright lights all night and it was a poignant reminder

of happier times back home before the blackout was imposed 4 years earlier.

Our craft proceeded independently through the

Strait and along the Moroccan coastline until we sighted

Mers el Kabir, a naval anchorage near Oran. This was where the Vichy French

fleet was neutralised by the Royal Navy on July 3,

1940. Our mission at this time was still not clear to

us but the arrival of a white ensign did not, on this occasion, signal

hostility. The event that did cause considerable chagrin, however, was the order

to 'get fell in' on the mole (jetty) for squad drill. Our performance fell far

short of King's Squad standard and would have brought tears to the eyes of our

Eastney training instructor.

Shore leave was granted to off duty men,

who were trucked off to Oran along a road shared with hooded figures astride

little donkeys. The question was where to go for entertainment? The main (and

only) local attraction was the brothel. Caution prevailed over curiosity with

most of us remembering the film on things prophylactic at the Lympstone Depot

cinema in our days as recruits. I opted for a relaxed haircut, albeit in a fly

infested 'salon'. Flies were a constant source of

great irritation wherever we served in North Africa.

Onward to Algiers, a grisly town off

limits since the discovery in a Casbah alley of two American soldiers separated

from their testicles. During the dark, silent hours,

two armed quartermasters were posted on the upper deck as a precaution against

marauding locals. A quartermaster's lot in the Mediterranean was otherwise a

doddle, because the tides of just a few inches

required no adjustment to the craft's mooring ropes.

Bougie,

further eastward, was a picturesque French colonial town. Our approach through

a forest of mastheads in the harbour had to be negotiated carefully before we

tied up. My dominant recollection of the place was the bemused expression of a

young dolly peering from her balustrade at the suggestive gestures of the

marines.

Apart from firing a few rounds at a bobbing

mine en route from Algiers, nothing had so far been fired in anger. But tension

was in the air as U boats were known to be active in the area. Lookouts were

told to be particularly vigilant on the next stage to Djidjelli, a quaint

harbour town fronted by mastheads of all shapes and sizes. We were joined by

other flak ships and sundry naval vessels providing the Luftwaffe with a prime

target.

Reconnaissance planes and other intelligence

gatherers had provided the enemy with accurate information on our location

and that night they attacked with a vengeance! They were no doubt aware that we

were the advance nucleus of a seaborne invasion force and their intent was to

remove the threat. Combined Operations vessels from the UK had now been joined

by their American built counterparts, such as LCIs

(infantry) and LSTs (tanks and heavy vehicles). They had crossed the Atlantic

for the Torch landings on Moroccan and Algerian shores and were now to be manned

by British crews (no marines) under the White Ensign.

Alerted by a warning siren on shore,

we ran to our action stations - the Oerliken gunners, the No 2s attending the

ammunition lockers and the pom-pom crews. Tension was high while we waited for

the bombers to arrive under cover of darkness. They dropped flares which hung

like bright inverted pyramids above the prey - us. On a signal from the bridge,

all guns opened up with bursts of a few seconds duration, the rest of the ships

did likewise. A colourful umbrella of contact-fused shells illuminated the sky;

a frightening sight to confront the Axis pilots. Meanwhile,

they released their bombs from a height most likely above the limit of our

trajectories. Sickening crumps could be heard all over the place as the bombs

hit the earth.

Strangely a feeling of exhilaration and

excitement gripped us. The ear shattering din generated a growing feeling of

immunity and confidence. After firing several hundred rounds,

the smell of cordite and a haze pervaded the upper deck, which had been

vibrating alarmingly under the detonations of our own guns and the bombs.

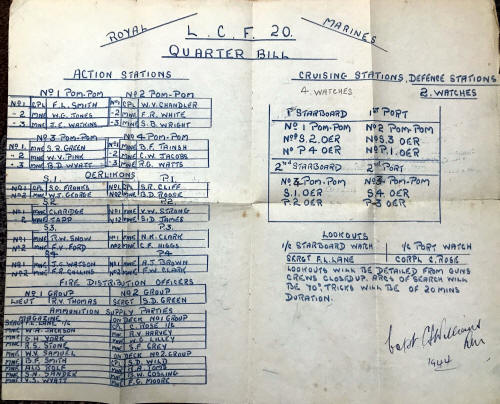

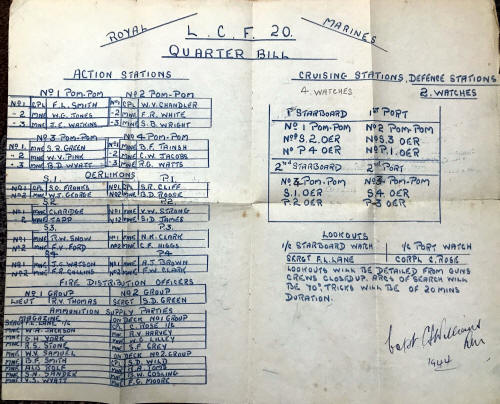

[LCF 20 crew duty roster, courtesy of Ian

Foreman].

The

raid lasted about twenty minutes but we of the lower deck never learned of the

extent of the destruction and number of lives lost. We stood-by palpably

thankful for our survival but without sleep. The officers later expressed

satisfaction with the cool conduct displayed while under fire. LCF 7 had

prevailed, although many such hostile encounters were

to be endured in the weeks

ahead.

On our way to our, as yet unknown, operational

base, we reached the town of Bone. We eagerly anticipated some relaxation

and a spot of swimming in the warm sea. We dropped the kedge anchor a kilometer

or so off shore, whereupon we were taken on a 5 mile

march up a dusty road and back again, much to the amusement of our naval

brethren.

On to Cape Bon where the remnants of

German forces had, just days before, fled Africa in haste. Then down the

Tunisian coast to Sousse, a holiday resort. It was the antithesis of a

holiday romp. Shortly after arrival our 'bunting tosser' sighted the 'carrying

mail' flag on a halyard of the assault ship 'Queen Emma',

which was about to enter harbour. We were overjoyed to receive letters and

parcels from home, even though the news items were

stale. Later in the war, the much faster 'air-graph'

service was introduced for overseas forces. One marine, from Bristol, received a

parcel from his local WVS branch containing a woollen balaclava helmet, matching

scarf and gloves. The mercury at the time was topping 90f.

Sousse accommodated us for a week or two,

during which time we suffered air raids nightly varying in severity from

nuisance attacks to intense. One bomb blast flung those of us not secured to an

Oerliken on to our backs. Lack of sleep was causing frayed nerves and many

resorted to chain-smoking. The morning ritual of 'up spirits' was observed with

greater gusto than normal. Unspoken odds of our chances of survival were

shortening - but around this time the expression 'Lucky 7' was beginning to

circulate. However, as though to counter this growing feeling of optimism,

a mined LCT came alongside containing bodies in the murky water of their flooded

well-deck and a marine on a neighbouring LCF was decapitated by his own loaded

Oerliken gun.

On the lighter side,

we were attracted to an impromptu Sods' Opera featuring a cast from the

victorious Desert Rats. Every squaddy wanted to participate on the cinema stage.

There were jugglers, tin horn blowers, corny, filthy gag tellers and a chorus of

Lili Marlene. The show was a glorious mixture of spontaneity and exuberance

performed by happy veterans, many of whom had fought

all the way from El Alamein. It was a never to be forgotten experience and a

privilege to be there among them. Many were part of the 51st Highland Division,

who were soon to be transported to a hostile shore in southern Europe by ships

of Combined Operations.

On another liberty trip,

an oppo and myself wandered into the deserted town making our way to an

abandoned fort. Notwithstanding the possible presence of booby traps,

we grubbed about in the detritus for souvenirs but found only shoddy insignia.

Returning to the ship along the once impressive waterfront,

we looked into the vacant, windowless villas, still determined to find a memento

of the place. Defying my conscience and a roving Red Cap patrol (military

police), I plucked a natty blue crystal chandelier from a ceiling,

imagining how it would beautify a certain ceiling in Blighty. The spoil of war

was secreted aboard and stowed deep in my locker and that was that... for the

time being.

While ashore that day,

I drank un-boiled water to slake a thirst,

ignoring a rumour that the Boche had contaminated the local wells. Within hours,

I contracted a virulent fever, which led to isolation

in a hot, fetid, rope-cum-paint store. There I writhed, sweating profusely for

two days until a Service doctor diagnosed enteritis and ordered my dispatch to

the military hospital at Monastir. Once under the tender ministrations of Queen

Alexandra's nursing sisters and a captive Italian bigwig orderly, I quickly

recovered. Delighted to be back on board for light duties,

I reflected on my earlier misdeed

and, sensing a bad omen, offloaded the chandelier on to a grateful matelot,

earnestly hoping that no harm would befall him.

Pantellaria Pantellaria

The first indication we had that an offensive

action was in the offing was when the sick berth attendant, himself a denizen of

the mess deck, was told to set out his stall in readiness for possible

casualties arising from an imminent battle. When later that same day all hands

were piped to assemble below to be addressed by the Captain, we knew then that

the balloon had gone up.

[Map courtesy of Google data. 2017].

'Stand at ease, lads,' he commanded, then

disclosed that we would be sailing in a few hours to the island of

Pantellaria, a fortified island naval base of Mussolini's. It was about 100

miles distant and H hour was to be in broad daylight at 12 noon! The Captain

explained our role in a combined operation involving landing craft, heavy naval

units and supporting aircraft. Being of shallow draught,

it was planned that we would sail close inshore and shoot up unspecified land

targets as well as keeping a watchful eye on the sky. He admitted it was a

potentially hazardous mission then added, 'Let's have no heroes, keep your heads

- I want to see you all returning safely home. Good Luck!' A short prayer

followed then 'Carry on' from the coxswain.

Apart from his duties on the bridge and

appearance on evening rounds, we did not see a lot of

the Captain. An occasional aside perhaps but no real rapport with his ship's

company up to that stage. However, as time went by, we

recognised the qualities of a kindly, modest and good humoured man - albeit no

swashbuckling Hornblower! He was an RNVR lieutenant, 40 something, a one time

Brooklands racing driver, who was afflicted with bouts

of recurrent malaria. Considering our vessel was a 'small ship',

the Royal Marine officers were a bit

remote from their detachment but, nevertheless, an aura of agreeableness

prevailed overall. It was a happy ship without a doubt.

We

steamed through a sleepless and apprehensive night. After breakfast there was

much smoking and feverish nail biting as the high ground of

Pantellaria came into view. We saw Bostons and the new twin fuselage

Lightnings undertaking low-level bombing through puffs of desultory ack-ack

fire. Our senses were on high alert as we approached the shore at a distance of

about half a mile. We

steamed through a sleepless and apprehensive night. After breakfast there was

much smoking and feverish nail biting as the high ground of

Pantellaria came into view. We saw Bostons and the new twin fuselage

Lightnings undertaking low-level bombing through puffs of desultory ack-ack

fire. Our senses were on high alert as we approached the shore at a distance of

about half a mile.

[Photo; Bombs by the ton bursting on the docks and harbour

before the landing craft went in. (© IWM (A 17667)].

To the south, a gleaming mass of

aircraft approached, dead on time. They were Flying Fortresses of the US Air

Force in formation and about to demonstrate the destructive power of saturation

bombing. Directly above our heads at two or three thousand feet it was like a

giant matchbox tippling its contents. It was a fearsome and terrifying sight

that caused the sprawling island target to be completely enveloped in smoke and

dust.

The haze slowly cleared to reveal a flattened

landscape, devoid of cranes, barracks, warehouses and dwellings. The odd fire

burned and there was an eerie stillness. We were geared up to do our stuff on

LCF 7 but there was nothing left standing to hit except a couple of sturdy

pill-boxes whose occupants had disappeared. To compound the plight of Italian

soldiers emerging from mountainside foxholes waving white flags, the cruiser

Orion started slamming the area with salvos of 6 inch shells - quite

unnecessarily in my reckoning. The British troops disembarked unopposed.

The order went out that LCF13 should act as a

guard ship in the island's harbour overnight. She took up position while we set

sail for Sousse, speculating on the next step of the campaign. During the

ensuing hours, enemy bombers plastered LCF 13

mercilessly and many casualties resulted. The craft ended up on the rocks, a

total wreck. We were all profoundly shaken and disturbed by the intensity of

this vengeful attack.

Rest &

Recuperation

Midsummer in Tunisia was hot and sleep

did not come easily. In our dormitory there were 40 odd hammocks slung closely

fore and aft, resembling a tin of bent sardines.

During middle watch, a cacophony of grunts, farts and

snorts could be heard! Fortunately, since the threat of air raids had subsided,

we had the option of rigging our hammocks on the upper deck, or just laying a

blanket down. In my case, a spot close to the port

forward pom-pom gun. The down side was that it became quite chilly during the

night and dewy towards dawn. Even to this day, I

regard a hammock as an abomination not to be recommended.

In early July, the

planners decided that LCF 7 and company should move to

Malta. Two hundred miles of dangerous waters lay before us and,

as always, vigilance was vital as we had no Radar, RDF

or Asdics. In the event, the journey was uneventful

and we reached the George Cross island and berthed at Sliema Creek. The prospect

of an evening in the main street of Valetta, the capital, was something to

relish. What an eye opener it turned out to be for us callow youths from the UK

provinces. The many bars along this loosely blacked-out thoroughfare churned out

popular songs for the delectation of boozing sailors from half a dozen navies.

There was a rich mixture of spivs, gays and transvestites,

which could best be described as extra curricula in the university of Life.

While we were in Malta,

a good story did the rounds. The US fleet on entering the Grand harbour of

Valetta signalled to the RN flagship, "Greetings to

the world's second biggest navy." In no time the RN Flagship replied, “Thank

you... and welcome to the world's second best.”

Sicily Sicily

[Map courtesy of Google data.

2017].

A feeling that further offensive action was

imminent turned to reality when all hands were piped for another homily from the

Captain, followed by a short service. This time the destination was Sicily, a

hundred miles away to the north. All warlike preparations completed and mail

taken ashore, we departed and took up station along with many others on a sea

that was the roughest we had yet encountered. We spent a wet, wind tossed night

exposed and soaked on the gun platforms, quietly praying that the minesweepers

had cleared the approach channels.

The soldiers on the smaller LCIs and LCTs, must have been greatly relieved when

the storm blew itself out and the Sicilian shore loomed up in the early morning.

It seemed to us that all ships had reached the target area unscathed, thanks in

large measure to an earlier bombardment by battleships, cruisers and a monitor.

It was some time before the enemy returned fire from a battery about 2 miles

away. We could see advancing plumes in the sea as the gunners found our range.

Thankfully a destroyer in our sector swiftly pin-pointed the on-shore muzzle

flashes and snuffed out the "offender" with some brilliant gunnery.

The

assault troops and their vehicles were well established ashore before

the first flight of high level enemy bombers appeared. They were

outside the effective range of our guns and they hit a liberty ship

carrying ammunition, blowing it to

smithereens. Later in the day, the

camouflaged, grey Mauretania arrived on the scene. She discharged

boatloads of troops, then quickly vanished over the horizon out of

harm's way. Fighter-bombers came swooping in out of the sun to be met

by a curtain of varied flak. Their persistence kept us lively

throughout the day and near-misses caused us some palpitations. The

same pattern of activity continued for a few days until the now empty

ships dispersed. The

assault troops and their vehicles were well established ashore before

the first flight of high level enemy bombers appeared. They were

outside the effective range of our guns and they hit a liberty ship

carrying ammunition, blowing it to

smithereens. Later in the day, the

camouflaged, grey Mauretania arrived on the scene. She discharged

boatloads of troops, then quickly vanished over the horizon out of

harm's way. Fighter-bombers came swooping in out of the sun to be met

by a curtain of varied flak. Their persistence kept us lively

throughout the day and near-misses caused us some palpitations. The

same pattern of activity continued for a few days until the now empty

ships dispersed.

[Map courtesy of Google data. 2017].

One beneficial by-product of the under-sea

explosions was the appearance of hundreds of concussed fish on the surface.

Volunteer swimmers were summoned to gather enough to provide suppers of fried

hake for all, a real delicacy in the circumstances. However, there was more

gruesome flotsam in the form of bloated uniformed corpses drifting by, victims

of an abortive air-drop off Licata on the eve of D Day.

An incredible, almost comical incident occurred

while we were swanning around Avola. A FW fighter plane hopped over a nearby

hill and cruised in a tight circle at masthead height. The pilot was clearly

visible and we were surprised he neither strafed nor bombed the targets below.

He must have been a pacifist or had run out of ammo. Before we collected our

wits and depressed the Oerlikens ready for action, he was gone.

As our army advanced up the eastern flank of

the island, the Americans were

doing the same in the west as the enemy were

driven north. First Syracuse port was opened up and then farther on Augusta,

which was capable of accommodating an entire fleet. We entered its harbour

through a defended boom and anchored in the midst of a host of ships from MLs to

a battleship. Security and defensive measures were

tight, since the battleships Queen Elizabeth and

Valiant had been sunk in Alexandria harbour by Italian charioteers. All capital

ships in the Mediterranean were now strictly protected at anchor from enemy

surface and under-sea predators.

The Luftwaffe were of course unaffected by

these measures. From the first night at Augusta,

flares were dropped at dusk and bombers assailed us relentlessly. The menacing

drone followed by whistling bombs were countered by a hail of projectiles

ranging from calibres of .5 to 4.7 inches. Our LCF 7 crew were by now reasonably

case-hardened... or so we thought, but these sustained aerial assaults spread

over several hours were a new experience. The simultaneous clatter of our guns

in actions over consecutive days had a deleterious effect on our nerves and

eardrums alike. Sleep was a luxury and by now we were all chain smoking. The

ordnance artificer earned his corn during this period,

as he serviced guns which were firing up to 900 rounds a night.

On the balance sheet of nocturnal destruction,

I cannot comment, except that every morning brought a deceptive serenity and no

perceived damage. Whatever, it was all a monstrous waste of lives and material

on both sides. Our own rounds shot into the sky no doubt also contributed to the

carnage as they fell to earth. One of our own men suffered a wound to his chest

from a piece of shrapnel from one of our guns.

Neighbouring ships at anchor were many and

varied, the most incongruous of which was a Chinese river gun boat sitting

sedately on the surface like a flat iron. Another was the Lascar (a sailor from

the East Indies) crewed Alletta, a tanker carrying precious drinking water from

Bournemouth! The tanker Brown Ranger, a blue ensign job, with a big basket-like

spark catcher atop the funnel, gave rise to some concern. It was loaded with low

flash fuel and seemed to court our protection from a mere cable length distance.

The

monotony of the daily diet continued and then worsened when the Purser's store

ashore provided us with captured Italian hard tack and tinned meat. The former

resembled mini slabs of Cotswold stone and the 'horse' was 50% bright yellow

chunks of fat. Then, out of the blue the battleship's

bakery came to the rescue with a sack full of freshly baked white bread! At tea,

on the dogwatch, jam butties never tasted so good! The

monotony of the daily diet continued and then worsened when the Purser's store

ashore provided us with captured Italian hard tack and tinned meat. The former

resembled mini slabs of Cotswold stone and the 'horse' was 50% bright yellow

chunks of fat. Then, out of the blue the battleship's

bakery came to the rescue with a sack full of freshly baked white bread! At tea,

on the dogwatch, jam butties never tasted so good!

[Photo;

A British Universal Carrier Mark I comes ashore. © IWM

(NA 4183)].

Our depleted stocks of ammunition were

replenished when a lighter came alongside. Once transshipped the lot had to be

greased in situ. A detail of grease monkeys, myself included, was sent below. In

the course of this messy duty an enormous explosion rocked the ship. We

scampered up the hatch ladder on to a drenched upper deck to see an expanding

circle of disturbed sedimentary water close by. A fighter-bomber had sneaked in

from the sun and caught us unawares. It was the closest shave to date and we

returned below to the magazine with some misgivings.

However, in the following days,

the threat of daylight attacks subsided and 'shore leave' was in prospect. We

cleaned up our best kit in readiness for a trip to Catania to see the girls of

the town at the foot of Mount Etna. Enjoying the feel of freedom and a return to

a mixed society, we wandered the streets of the town

centre and then down to the narrow harbour where, it was alleged, the retreating

Germans had ditched their whores on departure. This day,

all we saw was a wrinkled old man pulling a squid out of the water and then

killing it with a savage bite of its 'neck.'

I used my meagre BMA pay on a posh haircut, a

bottle of muscatel (wine) and a box of lemons for my mother. We were granted a

concession by the postal authorities to send a parcel of lemons, a long since

vanished commodity back in the UK. The fruit was delivered intact to a delighted

parent a week or so later. I repeated the gesture with a box of pressed figs but

this time the whole consignment was full of ants and went into the dustbin on

arrival. It was a memorable day out albeit without fraternisation, the local

talent having had their fill of occupying troops.

When it came to entertainment we did our own

thing. In our case there was no wireless, newspapers, books, dartboard or diary

to record tittle-tattle. At one stage, a moral

boosting outdoor concert staged by Nat Gonella and his American band was muted

but didn't come off. We were left with tombola sessions and bless him, Stripey,

a two badge leading hand, who could be persuaded with

the promise of sippers (donated rum) to perform his mess deck strip tease

spectacular, accompanied by the strains of mouth organ and paper comb! For the

finale, like a jubilant bride casting her bouquet, he would remove his briefs,

throw back his greasy head and toss away the grotty garment to reveal all, amid

a roar of applause. It was innocent fun with no implied sexual tones as may be

construed these days.

When we did play tombola, the caller was

something of a banking wizard, calculating, as he did

equitable stakes from 5 different currencies circulating - Sterling, BMA,

Gibraltarian, Maltese and Italian lire. Come to think of it, the jackpot was an

almost worthless pot-pourri. We never did get around to uckers, the naval

version of Ludo.

Towards the end of August,

the army reached the Straits of Messina bringing the action in Sicily to an end.

The Germans, however, had achieved an orderly withdrawal across the water to the

toe of Italy, which was to be our next destination in

the bid to liberate Europe. Accordingly naval forces, LCF 7 included, were

ordered to move up the coast from Augusta. The boom was opened up and gradually

the vast armada filtered through, until it was our turn to hoist the hook and

leave the shallow backwater. The Ricardo engines revved up as the ship's company

took up positions to leave harbour - but we were firmly stuck on the bottom! The

Captain tried every manouevre in the manual, thrashing the surrounding water

into a frenzied froth but to no effect. The harbour was about the size of

Portland and emptied leaving only the boom defence vessel, a few civilian motor

boats and one floundering flak-ship. Well, that was it, we thought, particularly

when the engines stopped and we all stood down.

We liberated a bottle of 'emergency' grog

intended as a fortifier on the eve of battle, a truly British quirk. An hour or

so later, when we were all in the grip of euphoria, a

big tug headed at speed in our direction creating a bow wave that spelt urgency.

In no time we were afloat and skulked away to catch up with the others. We

reached our destination and anchored in the deep and extremely cold water off

Riposta, below a smoking volcano.

Italy

We passed by Taormina which,

pre-war, was the mecca of more affluent Italian

honeymooners. Our mission, however, was much more

serious. We entered the Strait of Messina and took up a position in darkness

opposite the town of Reggio. They said it was El Alamein all over again as

hundreds of Allied field guns in the commanding heights above Messina opened

fire across the Strait. Thousands of shells whizzed overhead and thumped the

Calabrian mainland for an hour or so. Much to our relief there was no counter

fire from Axis batteries.

The bombardment ceased abruptly,

allowing the assaulting troops and their vehicles to land unchallenged. As

daylight broke, we had our first view of the undamaged

terra cotta roofs of Reggio, a place that had escaped the attention of Allied

artillery. It was not until mid-morning that a deceptive peace was shattered by

a succession of heavy calibre shells plopping ever closer to us. We were

powerless to reply but fortunately the offending gun was spotted and silenced by

one of the bigger navy ships.

LCF 7 settled in mid Strait for two or three

days, during which time enemy fighter bombers attacked

supply ships in our vicinity, respectful of our intense barrage as they did so.

The Luftwaffe must have been troubled by our prickly presence and picked the

flak-ship out as a target on one sortie. They swooped down through flak to

release a large bomb. Every one of us thought it was 'curtains' as it tumbled

towards the ship but mercifully it overshot and exploded some thirty yards

astern. Our hair and adrenalin shot sky-high and silent prayers were offered all

around. I recall we had more fish to fry that same evening.

During a subsequent daytime duel,

an LCM hurriedly approached. Its white faced coxswain requested permission to

secure alongside and to come aboard. Clearly shaken with fright, we ushered him

to the mess deck for a drop of precious 'neaters'.

Jack's composure was soon restored. As he and I chatted,

I sensed a familiar tongue and soon discovered that he hailed from my Wirral

village. His name was Cadwallader. On the final handshake,

we arranged a tryst at the Travellers' Rest when the war over. Well, I never did

see him again. He was last observed scudding along the waters of Scylia and

Charybodis a little worse for wear!

A humorous distraction from the deadly

encounters occurred when some of our men were bathing in close proximity to the

ship. An alert lookout noticed shiny black triangles gliding through the surface

waters. At the cry 'sharks' an undignified scramble aboard ensued. We were later

informed that the sharks were harmless 'baskers' but no one was convinced and

swimming was dropped as a leisurely pursuit.

A lull in the conflict locally allowed our ship

to enter the Messina harbour for stores and an opportunity for the detachment to

enjoy a spot of shore leave. The shops and cafes were, as expected, run down

establishments and offered only an austere selection of goods. However, the not

so shabby signorinas behind the counters appeared beautiful to our wholly un-practiced

eyes.

We were close to the heartland of the infamous

Mafia and we too had a crooked practitioner of that ilk aboard. The reprobate

possessed, for reasons known only to himself, a wad of outdated Irish Sweepstake

tickets which, to unwary foreigners (Sicilians for instance!), passed as

negotiable currency, bearing, as they did,

a motif of some obscure luminary and the inscription, 10 shillings (50p). He

would purchase, say, a cheap bag of nuts with his

'English money' and receive a handful of lira in change to be spent elsewhere.

No wonder they call us perfidious Albion.

One day an urgent signal arrived which was to

condemn everybody to indefinite shipboard confinement. An unexpected set back

had arisen during an attempted landing by Commandos at Vibo Valencia, some

seventy miles up the Calabrian coast. LCF 7 was to go with all haste to give

support at the troubled bridgehead, explained the Captain vaguely. The

pre-operational routine was put into full swing by the marines, while the

sick-bay tiff checked his box emblazoned with a red cross. It contained

bandages, tourniquets, morphia etc. The coxswain took the wheel and we cast off.

We pressed northwards for several hours,

passing the volcano Stromboli in the Lipari Islands. Late in the afternoon,

we saw the monitor Erebus firing its great guns at the shore, causing booming

echoes in the hills. We rounded the southern headland of a crescent bay and saw

an LCF lying motionless on the calm water. It was LCF 4, a participant in the

earlier landing, which had had fatal consequences for her. As we drew nearer,

we saw her ensign being dipped at intervals - a morbid indication that bodies

were being committed to the deep. All of us watching thought 'but for the grace

of God....' and we all felt foreboding.

An ML presently approached carrying a senior

naval officer, who hailed our Captain. We were to turn

about and sail parallel to a heavily wooded and seemingly benign shore line

about half a mile distant. The Erebus had, by now, ceased bombarding and the

sound of small arms fire from the battle area could be heard beyond the northern

headland, where we imagined Vibo Valentia lay.

A muzzle flash was seen from an enemy tank or

mobile gun concealed in the woods. Two ranging shells exploded in our wake, then

a third shot hit us a shuddering blow and erupted in a shower of sparks below a

midship Oerliken. Our pom-poms were clearly no match for

their longer range and greater

penetration power. Even our armour piercing shells made little impact on the

cleverly hidden assailant, a situation observed by the ML officer,

who promptly ordered us out. The gunner of the stricken Oerliken, 'Duke',

sustained a bad injury to his arm and he was taken by a fast launch to the

hospital ship Vita. Miraculously there were no other casualties and only

superficial damage to the ship.

Fortunately for us,

the advancing Allied Army broke through to the beleaguered bridge-head during

the night. As an eyewitness from my lowly cockpit, the whole business appeared

to be a bit of a fiasco. We were designed to fight aircraft but there were none.

Instead we were shot up by enemy land based guns,

against which we had no defence or serious ability to

attack. Maybe the surviving lads of LCF 4, some of whom received deserved

gallantry awards, harboured the same thought... that an LCG or LCR would have

been a more appropriate craft for the task.

Return Home

Feeling somewhat dispirited,

we began the return journey home on the 8th of September,

the day that Mussolini capitulated and the 'Eyeties' gave up the ghost. For my

part, the good news was dampened by the accidental

loss over the side of a silver cigarette case... a treasured gift from my

parents. The Germans fought on, resulting in the

horrendous landings at Solerno and Anzio.

At Malta, our vessel

took on supplies for the long haul to the UK and we completed a general clean up

and perfunctory painting. We took the opportunity to send final air letters to

sweethearts and families back home and bought cheap bric-a-brac and small

items of exquisite lace as presents. On one of the Captain's rounds,

I was rather embarrassed when he publicly thanked me for writing a letter to the

'Duke’s' mother in Devon expressing the sincere wishes of us all that her son

would soon recover and rejoin her.

The next leg of our journey was 1000 miles to

Gibraltar - just four or five sunsets away. Apart from the occasional scare,

we reached the outpost of Empire safely. It was a brief fuelling and supplies

call and we soon entered the cooler waters of the Atlantic. On the outward

journey I had enjoyed the warmth and comforts of the ship's pantry but this time

I was keeping watch for 8 or 9 days. Our landfall was the Fastnet Rock Light, a

beacon on the Irish coast. It was a welcome sight indeed.

As we approached the coast of Pembrokeshire a

whopping mine impeded our progress for a while. A few shots were aimed at the

horned monster but in the end it was left to HM Coastguard to deal with it. On

arriving at our destination of Barry in south Wales,

we soon regained our land legs and revelled in bragging about our exploits to

Blodwen and Myvanwy. It was a great treat to walk out of the local chippy with a

newspaper bundle of steaming fish and chips. It would have been nice to have

telephoned home but we couldn't afford to and, in any event, none of our

families had a phone in the house.

The very last thrash of LCF 7's commission was

up the Irish Sea and the River Clyde to Glasgow. The saga of Lucky 7 - some

would say happy-go-lucky - could now be told. Despite seven month's privation,

Elizabethan style accommodation, frugal food stuff and a knock or two at the

door of eternity, we had happily survived. Of the original ship's company that

left England in April, only two were now absent, 'Duke' and an NCO taken off at

Augusta, suffering from stress.

Before picking up our sea bags to disembark,

the Captain and fellow officers thanked us all for a job well done and wished us

good luck. Then, with a deferential wink at the man

from HM Customs, it was up the gangplank for the last time with, it must be

said, a heavy heart.

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments including a generic

LCF webpage.

There are around 300

books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be purchased

on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner checks the

shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and paste the

title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's no

obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Peter Bull -

To Sea in a Sieve.

One of the great books

about Combined Operations in WW2. Actor Peter Bull's To Sea in a Sieve,

covers his complete wartime service but concentrates on his command of an LCT

(Landing Craft Tank) and HM LCF 16 (Landing Craft Flak).

Many humorous anecdotes.

ISBN: 0552103802 / 0-552-10380-2

Acknowledgments

This article by K White about HM LCF 7 (Landing

Craft Flak) was originally published in the newsletter of the Landing Craft, Gun

and Flak Association.

|