|

Landing Craft

Tank (Mark 4) 795 - LCT (4) 795

on D Day.

LCT (4)

795 Serving USA Forces on Utah

Background

This is the story

of HM LCT (4) 795 from early crew training to D-Day and beyond, seen through the eyes of the craft's electrician,

Royal Navy Wireman, Michael Jennings D/MX574620. The crew faced hazards together

off the Normandy beaches and shared many experiences but an unexpected event dispersed them without

warning. The

author never met any of them again.

[Photo; Sister craft LCT (4)

828 under power.

© IWM (FL 7101)].

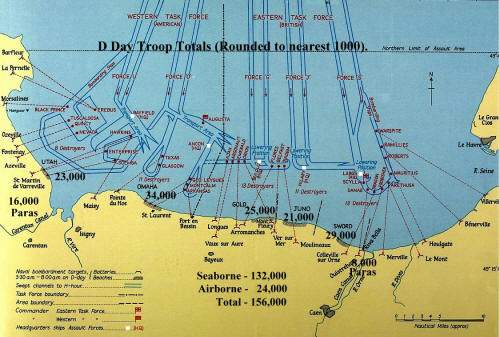

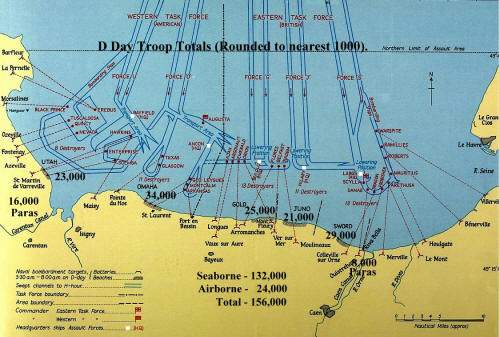

On the morning of D-Day, June 6th 1944, under the command of 21

year old Sub Lt Lyon, LCT 795 of the 52nd LCT Flotilla of the G LCT

Squadron was on Utah beach in support of the US 4th Infantry

Division.

Loading orders for the craft, in Michael's group, record that 795 was

carrying men of the USA's 531 Engineer Shore Regiment and landing

tables show that 795 was due on Tare Green sector of Utah beach at H-Hour

+ 320 minutes; just before mid-day.

Initial Training Initial Training

I joined the Royal Navy as a volunteer on May 11th 1943, and

reported to HMS Royal Arthur at Skegness in Lincolnshire on the east

coast of England. This shore establishment was formerly a Billy Butlin's holiday

camp requisitioned by the Navy as

a central reception depot for new naval recruits.

Following initial training, I was drafted to HMS Vernon

(Portsmouth), as a Junior Provisional Electrical Mechanic (JPEM) and then

to

HMS Shrapnel (Southampton) from where I travelled

every day to Totton to continue my JPEM course.

After a few weeks, several of us were taken off the

course and drafted to HMS Drake at Devonport

for onward draft to the Royal Navy Training Unit at Letchworth in

Hertfordshire, where we were placed on their Landing Craft Wireman course.

[The author, Wireman, Michael Jennings

D/MX574620].

Instruction

in seamanship at Troon in Scotland followed, where I joined 795 in the Gare Loch around the early weeks of 1944. From there, we undertook sea trials between Oban

on the west coast of Scotland and Lamlash on the Isle of Arran in the Clyde

estuary.

The daily routine was broken from time to time

by the exuberance of youth. Our Petty Officer motor mechanic and me were ashore and

missed the last liberty boat back to our landing craft. There was an exercise

the following day, so it was imperative that we were back on board in good time.

We spotted a dinghy tied

to the stern of a motor

cruiser, quickly untied it and proceeded to row back to

795. cruiser, quickly untied it and proceeded to row back to

795.

[Photos right;

Sub Lt Lyon (left) with his second in command, or

'Jimmy the One'].

We hadn't travelled very far, when we heard a

powerful boat engine burst into life. A searchlight swept the bay, soon picking us out in its glare

and, as it approached, we realised we'd borrowed the dinghy from a Naval Police Patrol vessel. Its crew were not amused and we found

ourselves on the receiving end of a well earned punishment from our Commanding

Officer.

However, I believe I saw a twinkle in his eye as he thought about us catching

out the Naval Police!

Preparations

for D-Day

After leaving Lamlash we headed south to Falmouth by way of the Irish Sea.

In Falmouth, around March 1944, Mulock ramp

extensions were fitted to 795's bow door, suggesting a designated beach in a

future planned landing was unusually flat.

There were many

British craft in Falmouth for refitting or repairs and US Navy craft from their

Navy's 'Force B Follow-Up' to their first wave of landings destined for the

American

sectors. Nights ashore were organised to avoid British and American sailors

sharing the same recreational facilities. The UK and US authorities knew how to

avoid conflict amongst the Allies! American

sectors. Nights ashore were organised to avoid British and American sailors

sharing the same recreational facilities. The UK and US authorities knew how to

avoid conflict amongst the Allies!

With our Mulock extension in place, LCT 795 departed Falmouth and

anchored at St. Mawes, where we fished to

supplement rations. Talking of which, an American soldier from Los Angeles

joined us to guard the US Army K Rations stacked on board. We nicknamed him GI

(Indian) Joe. I'm ashamed to admit that we stole two boxes but, fortunately,

there were no repercussions - nobody was counting in

those days!

[Photo; most of the crew in relaxed mood].

During early springtime

the pace quickened and preparations became

more urgent and intense. There were regular, often daily, practice landings with

our US Army troops on the beach at Slapton Sands. On one of many night-time

exercises, I saw

a ship burning in the distance. Next morning, in Brixham Harbour, all the American LSTs had their flags at half-mast.

For reasons which became apparent much later, the authorities suppressed the

news that a convoy of fully loaded US LSTs came under attack

from German E-boats, during which nearly 750 men were

lost. (Operation Tiger).

D-Day

The long awaited day, which we had trained so hard

for, was fast approaching. We embarked our US troops and tied up alongside other craft

in Dartmouth harbour. No-one could leave the vessel without

very good reason and an escort. Secrecy was paramount. Our

skipper told us ‘this is it’ and explained our part in the imminent invasion of France.

As

we departed Dartmouth, crowds of people gathered

to wave us off, no doubt having worked out that this was the long awaited invasion. We sailed on

for a while but diverted into Portland because bad weather had delayed the

planned landings for June 5th by 24 hours. The following morning, to

the distant horizon, the sea was full of landing ships and craft of all shapes

and sizes. The enormity of the spectacle made a lifelong impression on me. I was

only 18 years of age and recall saying to my shipmates…"We are about to become

part of history!"

The crossing to Normandy was very rough and sea

sickness amongst the American soldiers

was rife. They could not wait to get off our 'God damned boat.' There was no

escape from the smell of vomit, it was everywhere. I slept in the Oerlikon gun

pit where the air was fresher. We arrived off the Normandy beaches during the pre-dawn hours and stood off

as we watched Allied planes going over during the first light of dawn. Our run

to the beach was planned for approximately 1000 hours as part of the fourth

assault wave. Every man was given a tot of rum, even underage me. It tasted

really good. The crossing to Normandy was very rough and sea

sickness amongst the American soldiers

was rife. They could not wait to get off our 'God damned boat.' There was no

escape from the smell of vomit, it was everywhere. I slept in the Oerlikon gun

pit where the air was fresher. We arrived off the Normandy beaches during the pre-dawn hours and stood off

as we watched Allied planes going over during the first light of dawn. Our run

to the beach was planned for approximately 1000 hours as part of the fourth

assault wave. Every man was given a tot of rum, even underage me. It tasted

really good.

My action station was to operate the cable

brake drum when the Kedge anchor was lowered, as we approached the beach. On the beach

itself there were

explosions, which I thought was evidence of demolition work by our own engineers. However, an American soldier was sure they were 88mm shells from

German defenders taking their bearings on the Barrage Balloon flying above our

craft.

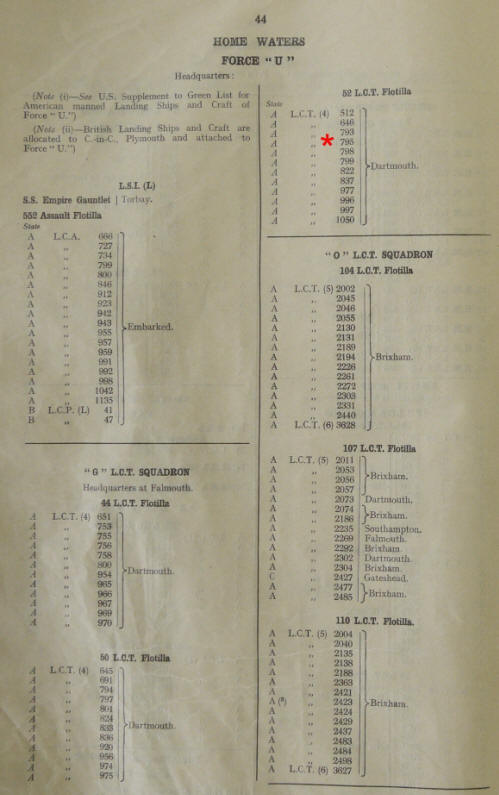

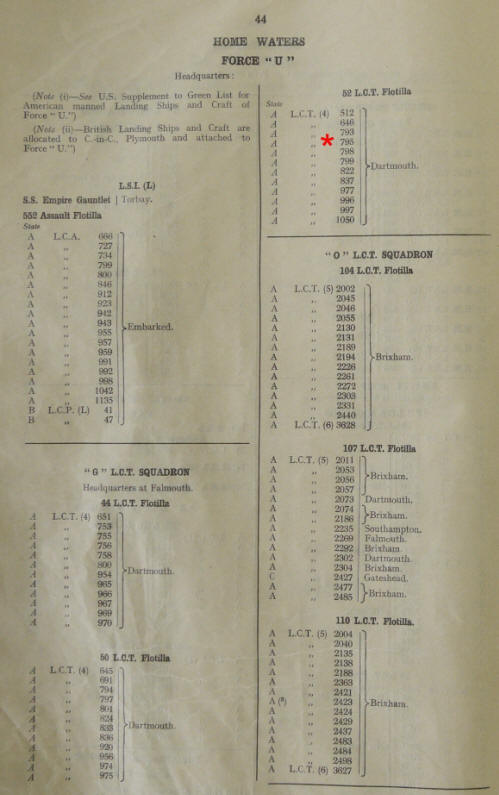

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List'

showing the disposition of LCT 795 just before D-Day].

Having

disembarked our cargo of men and trucks on to the beach, 795 was left stranded as the tide receded. Alongside us, also part of 52nd

Flotilla, was one of our sister craft HM LCT 996.

Since we were easy targets for German gunners,

we ran up the beach to seek shelter and saw shells landing between the craft,

which punctured holes in the side of 795. The damage was not serious and,

considering some of the trucks we had earlier disembarked were carrying high

explosives for demolition purposes, we

considered ourselves lucky. Had one of them been hit, 795 and all onboard would

have been lost.

As the shelling continued, I jumped into a

foxhole already occupied by an American soldier, who shared his K Ration

chocolate with me. He asked if I was a Commando. I replied, 'no fear!' and

explained my intention to return to England on the next tide. Other members of 795’s crew

took refuge in a blockhouse, where they found the dead body of a German soldier.

They took his helmet, Very pistol and a hand grenade as souvenirs. The

combination of youth and wartime made people very callous, but now, all

these years later, I wonder about him, his family, who he was and where he came

from.

We rejoined 795, retracted from the beach

and anchored off-shore until the following morning. We spent the night watching

tracer bullets beyond the beaches and feeling grateful to be out of harms

way.

Back in England,

795 was repaired at Milford Haven, including damage to her bottom caused

by an underwater object. Thereafter, we became

a military cross channel ferry. We operated out of Portland, carrying troops and tanks to the

Mulberry Harbour and other areas until the

harbour at Le Havre was liberated in September 1944. We

could go ashore there but the town itself was in a terrible state following allied

bombing and shelling. Back in England,

795 was repaired at Milford Haven, including damage to her bottom caused

by an underwater object. Thereafter, we became

a military cross channel ferry. We operated out of Portland, carrying troops and tanks to the

Mulberry Harbour and other areas until the

harbour at Le Havre was liberated in September 1944. We

could go ashore there but the town itself was in a terrible state following allied

bombing and shelling.

[Photo; LCT 795 on Utah beach, presumably taken from LCT

996 which was stranded alongside her between tides].

We continued working between England and Le

Havre until the early part of 1945, suffering only minor bumps and scrapes while

remaining operational

throughout.

Unexpected End to My Naval Career

HM LCT 795's

luck ran out on February 15th, 1945. It might have been early morning or evening,

I can't recall. Anyway, we were returning from Le Havre during the hours of

darkness in convoy, sailing in line astern.

From the mess deck I heard an almighty crash and the stern

bulkhead buckled. It soon transpired that we had run on to rocks and the craft immediately astern had

run into us. 795 lost power as water entered the fuel tanks and the

generator shorted, causing sparks to fly out of the funnel. We lashed 795 to

another craft and obtained power for lighting from her generator. We limped back to Portland Harbour where 795 was formally written off thirteen

days later. Her crew, including myself, were paid off and individually drafted to new posts. Suddenly, I

had lost all contact with my shipmates and sadly never saw any of them again. days later. Her crew, including myself, were paid off and individually drafted to new posts. Suddenly, I

had lost all contact with my shipmates and sadly never saw any of them again.

[Photo; The two beached craft waiting for the next

tide].

The craft that ran into us that night was HM LCT 1127.

She too was a veteran of the Normandy landings as part of the Royal Navy’s 59th

LCT Flotilla of Q LCT Squadron which formed part of Force B Follow-Up. On June 6th

1944, 1127 was under the command of Sub. Lieutenant Fred Clements RNVR.

I joined the Mk3 ‘Star’ HM LCT

7124, which was being 'tropicalised' for service in the Far East. However, I missed her

sailing since I was in Mearskirk Hospital at the time.

Later, albeit

briefly, I joined the crew of Landing Craft Gun (Large), LCG (L) 811 at

HMS Vansittart in Bristol. Her type were described by the BBC as 'mini battleships'

and her

heavy guns were manned by Royal Marines.

After 811, I attended

HMS Turtle, at Poole in Dorset, for training on rocket firing LCTs. While

there, news about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima

and Nagasaki was received, which brought the war to an end. After 811, I attended

HMS Turtle, at Poole in Dorset, for training on rocket firing LCTs. While

there, news about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima

and Nagasaki was received, which brought the war to an end.

[Photo right; Author on gun barrel of LCG (L)

811].

My time in the Royal Navy was coming to an end.

I was drafted to Plymouth as part of a 'Care and Maintenance Party' for empty landing craft that were

surplus to requirements then, finally, to

the Demobilisation Centre in Scotland for release in Class A on June 11th

1946.

I have always been pro-American and have an affinity with the country for

family reasons. My uncle emigrated there and became a naturalised citizen, later

fighting with the US Army during World War One. I felt sorry for the American

lads I met. They were all so far from home with all its comforts and security.

They told us about their country and their families. So many of them never returned to their homeland.

Photo

Gallery

1) AB 'Ma' Leat. 2) LCT 795's Signalman or

'Bunts' as he would have been known manning one of her 20mm Oerlikon

guns. 3) Cox and Motor Mechanic on Oerlikon. 4) Fishing in Scotland. 5) Gordy (Geordie from NE England?) outside ramp door winch. 6) GI Indian Joe. 7)

LCT 795's stoker, referred to as 'Scouse'

from Liverpool. 8) Author on tank deck.

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books

listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be purchased on-line

from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and paste the title of your

choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's no obligation to

buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Supplementary

note of peripheral interest

With 795 were other British manned Mk4 LCTs; LCT 758 with the 4th

Field Artillery Battalion, LCT 798 with men of the 3rd Battalion 12th

Infantry, LCT 799 with men of the 1st Battalion 12th

Infantry, LCT 822 with men of 531 Engineer Shore Regiment (same as LCT 795), LCT

977 with men of the 12th Infantry, LCT 974 with 29th Field

Artillery Battalion and LCT 996 with elements of the 1st Engineer

Special Brigade.

Correspondence

I believe my late father, Graham Robert Taylor (Bob), was on the 795's sister

ship which beached on D Day. He told me about this incident many years ago and

it's great to see the story has been archived for all to read. He had an

eventful war having been torpedoed in the Mediterranean in a flotilla returning

from north Africa. He and six others survived and were picked up some seven

hours later one of whom was

was named Lou

Boozey from the Teddington/Twickenham area.

Father was immensely grateful to his rescuers for the clothes he and his mates

were given even if he looked like a ragamuffin with bits of Navy, Army and Air

force uniforms! When they arrived in Poole Harbour there was a lot of drinking

and they all ended up in the Fireman’s hut on the harbour for the night very

much worse for wear! After what they had been through, in the morning they were

allowed to get on with the job in hand without reprimand.

I would

love to know if the ship my father was torpedoed in was the HM LCT 996. My father

later reported to his skipper that he had heard a ticking sound before the ship

blew up and was absolutely convinced it was a limpet mine, but the skipper put

the noise down to the generators on another ship.

Regards Regards

Peter Taylor

Acknowledgments

This account of HM LCT 795

was prepared from the notes of RN Wireman Michael Jennings D/MX574620. They were transcribed by Tony Chapman, archivist/historian for the LST

and Landing Craft Association (Royal Navy) and further edited by Geoff Slee for

website presentation, including the addition of photographs,

maps etc. Chapman, archivist/historian for the LST

and Landing Craft Association (Royal Navy) and further edited by Geoff Slee for

website presentation, including the addition of photographs,

maps etc.

|

Back in England,

795 was repaired at Milford Haven, including damage to her bottom caused

by an underwater object. Thereafter, we became

a military cross channel ferry. We operated out of Portland, carrying troops and tanks to the

Back in England,

795 was repaired at Milford Haven, including damage to her bottom caused

by an underwater object. Thereafter, we became

a military cross channel ferry. We operated out of Portland, carrying troops and tanks to the