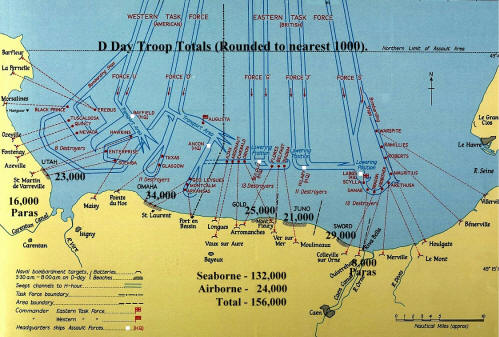

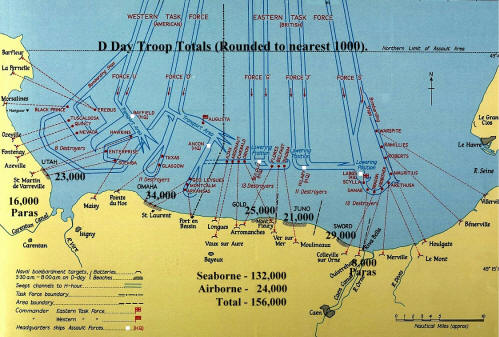

Landing Craft Tank (Mark 4) 821 - LCT (4) 821 on D Day.

From the Normandy

beaches to Bordeaux on the River Garonne as a timber barge.

Background

In common with most landing craft, His Majesty's LCT (4)

821 was destined to land on the Normandy beaches on

numerous occasions as she transported

the Allied armies with weapons, equipment and supplies across the English

Channel... but the experiences and impressions of their crews were very

individual. On D-Day, Signalman Eric J Loseby served

on HMLCT 821 of the 42nd

Flotilla of ‘I’ Squadron Landing Craft bound for

Sword beach. This is his story.

Audio

version by pod-caster, Paul

Cheall http://www.fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk/

Audio

version by pod-caster, Paul

Cheall http://www.fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk/

[Photo; LCT(4) 828, identical to 821, unladen at sea.

© IWM (FL 7101).]

Initial

Training

The 4th of June, 1944, was a day of intense activity amongst

the flotillas of landing craft at Portslade Harbour in Sussex. The streams of military

vehicles that had been pouring into town were finally chocked and chained to their

allocated deck-space on their allocated landing craft

and, in the case of the Mk4 Landing Craft

Tank 821 (LCT 821) of the 42nd Flotilla on which I served,

our passengers were making themselves as comfortable

as possible aboard. Quite a challenge on these flat bottomed

craft, that might otherwise be described as floating

pontoons with a couple of powerful engines at one end and a heavy ramp door at

the other!

The previous day, flotilla

crews were briefed by the "top brass" on the forthcoming landings on the French coast. Such was the

secrecy that the briefing took place in a well guarded cinema in Brighton,

Sussex. This was not just another exercise, of

which there had been many in the previous weeks and months,

and after returning to LCT 821, we were confined

to the boat. For the first time whilst keeping harbour watch, we carried service revolvers

with live rounds.

My preparations for war began with 10 weeks of gunnery and seamanship

training at HMS Ganges, a naval shore base at Shotley,

Ipswich, Suffolk , followed by many

months of Combined Operations exercises at HMS Dundonald on the Ayrshire coast

in south west Scotland. We trained in small arms weaponry

and physical fitness through endless rounds of

assault courses. At nearby Troon

Harbour, we were introduced to landing craft, which

later included day long

trips to Brodick Bay on the Isle of Arran, where we learned the

many skills required to operate a landing craft tank.

The flat bottomed landing craft were designed to

land directly onto unimproved beaches

just ahead of high tide, speedily disembark their cargoes and

make their way back to England before the tide went out. If there was any delay,

the landing craft would be beached high and dry for about 12 hours until the

next tide. The quick turnaround was

aided by partly lowering the ramp and, with sufficient speed, forcing

the bows of the craft on to the beach to secure a good hold.

The flat bottomed landing craft were designed to

land directly onto unimproved beaches

just ahead of high tide, speedily disembark their cargoes and

make their way back to England before the tide went out. If there was any delay,

the landing craft would be beached high and dry for about 12 hours until the

next tide. The quick turnaround was

aided by partly lowering the ramp and, with sufficient speed, forcing

the bows of the craft on to the beach to secure a good hold.

On the approach,

the heavy kedge anchor would be

slipped from the bed on the stern of the craft and the cable freely paid out. On

beaching, the slack on the kedge anchor would then be winched in and, with help from an occasional turn of

the propellers, the craft would be held at right angles to the beach. Once in

this position, the ramp would be fully lowered, giving added hold on the

beach. 'Un-beaching' was achieved by winching in the kedge anchor after raising the

ramp from the beach.

[Photo; the author,

Signalman Eric J Loseby.]

On completion of this phase of the training, we were issued with the now

familiar Combined Operations badge and given the option of a

specialist course for any trade applicable to landing craft crews.

Having learnt Morse Code at school, I opted for the signals branch, believing

that my little knowledge might give me a head's start.

After a short period of leave, I reported to HMS Pasco, a Combined Operations

signals school at Strachur, eighteen miles north of Dunoon

at the head of Loch Eck. During the 10 week course, we studied Morse

code by Aldis lamp, semaphore,

two-way radio procedures and

formation marching on the sports field to represent the manoeuvres of

landing craft flotillas as indicated by hoisted flags. The one light relief from

all this intensive learning was the occasional period of physical training (PT).

The ageing chief petty officer PT instructor had been brought out of

mothballs as a war time stop-gap measure. With a lively sprint he passed by the guardroom with

us bringing up the rear. To any onlooker the Chief appeared to be taking us on a

cross-country run but, after rounding the first bend in the road, we ‘left

wheeled’ through a gateway into a plantation! For the next hour or so, we lazed

around under the trees. Strange how matelots always seemed able to produce

cigarettes and a light, even when only dressed in their gym outfits.

HMS Pasco was completely surrounded by mountains and forests, so there was

little to distract us from our training. On completion of the course, we all

displayed the signalmans' crossed flags badge on our sleeves.

LCT 821

On

return to HMS Dundonald, I was assigned to the almost completed Mk4 LCT 821 at

a Glasgow shipyard. I ruefully hoped that I would now lead a more settled life.

On

return to HMS Dundonald, I was assigned to the almost completed Mk4 LCT 821 at

a Glasgow shipyard. I ruefully hoped that I would now lead a more settled life.

[Photo; the author right and

Coxswain of LCT 821 Albert Chapple taken in 1994 on the occasion of the 50th

anniversary of D-Day. This was the only occasion the two shipmates met after the

war.]

The average crew of such a craft comprised two officers and ten lower deck

ratings. Of the crew members I can recall; our commanding officer Sub

Lieutenant Rae from Croydon, Midshipman Hockings as ‘Number One’ from South

Wales, Motor Mechanic Charles Bratt, two stokers, one being named Moore, Wireman

(Electrician) ‘Jock’ Reaper from Glasgow, Gunners McQuade and Pitchford, the

latter from Liverpool, who manned two 20mm Oerlikon guns. Leading Seaman

Albert Chapple as Coxswain, two seamen whose names I can’t recall, one of whom

acted as cook, and myself, Signalman Eric Loseby.

LCT 821 was a drab battleship grey but she soon acquired

a refreshing coat of white paint with accompanying Mediterranean Blue

camouflage stripes. The painting job was undertaken by Dennys in Dunbarton,

15 miles down the north side of

the River Clyde from

Glasgow. We then proceeded to Largs, where our Oerlikon guns were tested and

then to Troon to take our place amongst our sister craft of the 42nd

LCT Flotilla.

Midshipman Hockings was the only other member of our crew with a working

knowledge of Morse and semaphore. When he was not on watch, I usually occupied the bridge with our

commanding officer and was also often called to the bridge, even when off duty, to

deal with the odd signal. As a consequence of my watches on the bridge with the officers, I was

constantly quizzed by other crew members for news. They were desperate for

information, since planned movements and destinations

of craft were, as a general rule, never made known beforehand

Following modifications at Irvine, brief periods at Lamlash on the Isle

of Arran and the quay at Castle Toward (HMS Brontosaurus), the 42nd Flotilla

sailed out of the Clyde estuary northwards to Oban, where a series of night time

exercises took place. On leaving Oban, we once more steamed northwards through

the Sound of Mull, the Sound of Sleat and the picturesque Kyle of Lochalsh to

Loch Broom. It was there that a Flower Class corvette took over escort duties

around the wild Cape Wrath at the north west tip of the Scottish mainland. En route,

we were diverted into Loch Eriboll for a few days

during rough weather, when a drifting mine was spotted. LCTs were difficult to

steer at the best of times but in rough seas and high winds they were very

difficult to control, so avoiding

a mine was by no means certain.

Joint Training Exercises

We made our way along the north coast of the

Scottish mainland to Thurso, where

fresh supplies were taken aboard. We normally had adequate supplies of good

food - tea and coffee were always on hand with egg and bacon for breakfast most

mornings and roast beef for dinner several times a week, all, of course, washed

down with the customary neat tot of rum. On leaving Thurso, we took a southerly

route down the north east coast of Scotland to the Beauly Firth near Inverness.

This became our home for

the latter half of the winter of 1943.

[Map; courtesy of Google. 2019.]

The

high landscape around us was completely snow covered throughout the whole of

the time we were there. These cold conditions made life on board unpleasant. The condensation on the mess-deck

was so bad that we slept with our oilskin

coats draped over our hammocks to avoid being saturated come the

morning. When at sea, the open bridge afforded little protection from the elements...

it consisted of four armour plated sides but no roof. Those who occupied the bridge

during exercises at sea spent many miserable hours thoroughly soaked and frozen.

It

was in these inhospitable winter waters, 600 miles north of the English

south coast, that we endlessly practiced beach

landings with army passengers destined for the Normandy beaches, as well as other manoeuvres in convoy, until our reactions to events became second nature and we

thoroughly understood the unusual characteristics of our flat bottomed craft.

In the heat of battle every second would count.

D

Day Beckons

As the early summer of 1944 approached, the 42nd Flotilla proceeded

to the south coast of England, calling at Leith, Immingham and Harwich. We

passed through the Dover Straits under cover of darkness to

arrive at Portslade. The contrast between the weather on

the south coast of England in summer and that of

the north of Scotland in

winter was truly amazing. With most of our training

completed, we spent a good deal of our time in harbour

with shore leave in Brighton and Hove.

One of our crew, known affectionately as Jock from Scotland, arrived back on board

after shore leave carrying a large wicker chair, not unlike those typically seen on the

verandas of

plush hotels along the Brighton sea front. He had

acquired a lift from a motor cyclist and we were left to imagine the sight of

Jock and his wicker chair on the pillion seat of a motor cycle! The chair

found a good home….on the quarter deck of LCT 821! Briefing

sessions were held when we learned our destination.

The day arrived when there was unusual activity in the harbour.

It was clear that the time had come to put the many months of training to the

test. Late in the evening, puffs of smoke issued from funnels, as main engines

were fired up. One by one the vessels in our flotilla slipped their moorings and proceeded out of

the harbour

to an assembly area off Newhaven, where we dropped

anchor. The change in the atmosphere amongst our crew and our army passengers

was palpable as animated conversation gave way to our own private thoughts about what lay ahead.

Rumours began to circulate that, due to unfavourable weather, there was to be a postponement

and, with the arrival of dawn, LCT 821 still

stood at anchor, although now joined by many other craft and ships of various

types. During the day of June 5th, 1944,

the military personnel were ferried ashore to Newhaven and exercised around

the docks area, while we rode at anchor from the

stern capstan. This afforded little comfort in all but a calm sea, as the flat

stern of the craft reacted to each wave with a shudder throughout the length

and breadth of the craft... and always present was the seemingly incurable

ingress of water through the propeller shaft glands. This was made worse by

exposure to an oncoming sea and, after a while, about a foot of bilge-water

would be swilling around the mess-deck directly above.

D-Day

With improving weather conditions in the evening of June 5th,

the vast assembly of craft and ships began to move, setting course to the

south under heavy and darkening skies. We all received a copy of the now

familiar message of good luck from General Eisenhower. Our passengers were a

mixture of Royal Marines, Infantrymen and

members of an RAF Signal Corps. Many suffered gravely from sea sickness - the luckier ones

were offered our hammocks, since none of our crew would find time to sleep that

night.

For the greater part, the outward journey was monotonous. There was little

room and nothing to see other than the dim blue stern light of the craft ahead.

The

tedium was broken only by the occasional increase or decrease in engine revs to

maintain a safe distance. By the first light of dawn on the morning of D-Day, we arrived at the

lowering position some few miles short of the Normandy beaches, the French

coast being just discernible on the horizon.

At this point,

various groups of vessels began to break away to

their assigned sectors, giving us a feeling of isolation and exposure. Before LCT 821 began her advance, Sub Lieutenant Rae produced an

enormous White Battle Ensign to replace the usual one that flew from our mast.

During our dash for the beach, I tried to ignore a couple of water spouts on

our portside. Obviously intended for us, they were

the first visible sign that the natives were not at all friendly!

The heavily laden and

exceptionally low cloud absorbed

the orange glow

from the fires caused by Allied shells and rockets, which

were fired in advance of the initial assault troops

landing. As we drew closer

to the beach, we saw a typical seaside residential area with a promenade and a roadway at the top. The houses were

closely grouped on the far side, most of which were burning freely,

while others were already just

smouldering ruins. By the time we reached the shoreline, the beach was cluttered with stranded vehicles, tanks

and

landing craft, not to mention the

enemy's beach obstacles.

Despite the difficulties,

we successfully beached and our ramp was eventually lowered and unloading

commenced. We soon attracted the attention of snipers installed in the

upper windows of one the few houses left standing. I heard the hiss of a

bullet when it passed between myself and Sub Lieutenant Rae as we stood on the

open bridge. After that we kept our heads down,

despite wanting to monitor mortar

bombs landing further along the beach, which had been fired from gardens at the rear of the

burning houses.

We

saw many

gruesome sights around us, including a number of tin

and enamel tea mugs floating a few yards from the water’s edge along

the shoreline. When the tide went out, we could see they were

attached to the knapsacks of earlier casualties floating face down in the

water and now being deposited on the sand.

It usually took twenty

minutes to unload our cargo but we hoped to break

all records, as the Germans were expected to

disrupt the landings with their heavy artillery.

However, fate conspired to detain us,

when we discovered that our kedge anchor cable had parted

having fouled one of the beach obstructions. It was this anchor cable that

would normally winch the craft off the beach. LCT 821 settled on the bottom as the water

receded. We

were stuck for the rest of the day. With no

sea water to cool the engines they were shut down, which also shut down the lighting.

821 became a dark,

silent hulk except for the occasional rattle of flying debris against the

hull. We were grateful to have an old

fashioned coal burning stove on board, since we could

still have hot food and

drink. We were in an exposed and helpless position,

so I also had a

shave to take my mind of things! Later in the day, a lone enemy fighter

bomber flew under the low cloud ceiling along the coast. As it passed directly above us,

we saw the pilot bale out, while his plane flew away into

the distance. It only took a few seconds to realise

the pilot was still in his plane and a bomb was coming our way! It exploded a few hundred

feet away along the beach.

821 became a dark,

silent hulk except for the occasional rattle of flying debris against the

hull. We were grateful to have an old

fashioned coal burning stove on board, since we could

still have hot food and

drink. We were in an exposed and helpless position,

so I also had a

shave to take my mind of things! Later in the day, a lone enemy fighter

bomber flew under the low cloud ceiling along the coast. As it passed directly above us,

we saw the pilot bale out, while his plane flew away into

the distance. It only took a few seconds to realise

the pilot was still in his plane and a bomb was coming our way! It exploded a few hundred

feet away along the beach.

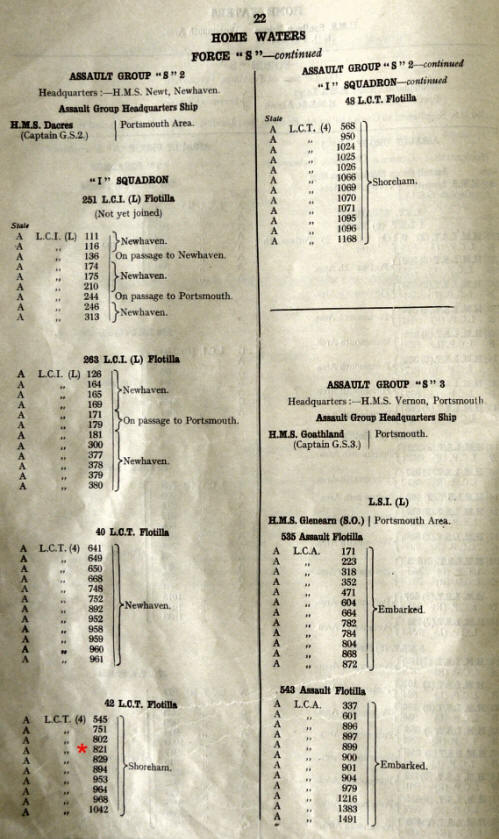

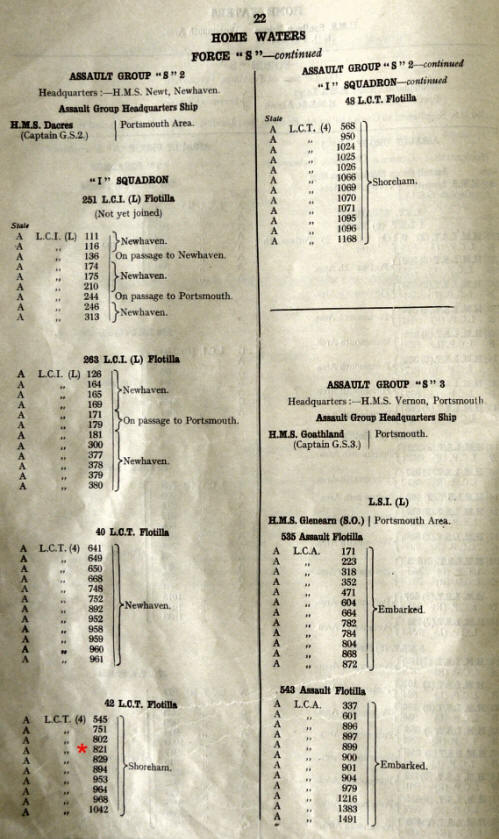

[An extract from

the Admiralty's 'Green List' showing the disposition of LCT 821 just prior to

D-Day.]

By this time Sub Lieutenant Rae had contacted

a Beach Control Party. We soon discovered that Midshipman Hockings, Coxswain Albert Chapple and I had volunteered to salvage the lost kedge anchor with the aid of a

giant recovery truck. As the beach was not yet clear of mines, we walked in the vehicle’s tracks as it towed the spare cable out for

attachment to the kedge. We looked in awe at the many beach obstructions now revealed by the low

tide, all of which, thankfully, LCT 821 had missed as she made her approach.

These consisted of logs, with the bark still attached, forming enormous tripods

at the top of which were lashed large calibre shells with impact fuses

pointing seawards. There were also lengths of steel girder welded together in

criss-cross fashion with pointed ends presenting a hazard in all directions.

After securing the anchor cable, we hastily returned aboard to await the

incoming tide. A party of Germans appeared at the top of the beach. It was a

worrisome sight for us, in their unmistakeable

helmets and jackboots and seemingly without guards or escorts. They split into groups of four

and strolled down to collect the fallen ‘Tommies’, laying them in neat rows

above the water line. One German in particular was calmly smoking his pipe as

though he was pottering around in his

garden.

Never had an incoming tide been more welcome than on this occasion. As the

water lapped under the stern, Motor Mechanic Charles Bratt anxiously peered

over the side at the cooling water intakes. Once these were submerged,

he fired up the main engines.

Return

from Normandy

We were informed that 130

German POWs and a few wounded Royal Marines would be embarked for the return

trip and that no guards would be provided. We could spare only 2 crew members

for guard duty, which left us grossly outnumbered and vulnerable to attack, even

by unarmed men. We placed a row of tank chocks across the well-deck

as a boundary marker, confining the prisoners to the forward part of the ship.

Another crew member and I were armed with Lanchester rifles, under strict

instructions to shoot any prisoners

who crossed over the line. Our two officers also carried their revolvers.

It was a pleasure to feel the movement of the ship as the incoming

tide lifted us clear. As we prepared to leave, other craft were arriving on the high

water and a couple of LCI(L)s [Landing Craft Infantry (Large)] beached

alongside us. There was still occasional sniping from nearby houses and fire

was returned from the LCI(L)'s 20mm Oerlikons straight

into the open windows. Loaded with the usual assortment of tracer,

incendiary, armour piercing and high explosive rounds, the effect on the houses

at that range was devastating. The resulting blazing inferno was a fitting end to

our day at the seaside!

We cleared the beach area without further ado but, on gaining open water, it

became clear that LCT 821 had broken her back on the uneven and churned up beach.

However, since LCTs for the most part are constructed of separate watertight ballast tanks,

there was not much to concern us, just so long as the plates held the two halves

together.

Our prisoners soon settled down into their allotted space.

After a while,

one of them came towards us holding up a kettle, indicating that water was

needed for brewing up. Watching over them for so many hours, we came to realise that they were little different to ourselves.

Some were dressed in civilian clothes and others in uniform. One spent

a great deal of time scraping his uniform with a penknife in an attempt to

remove what appeared to be the dried flesh and blood of a less fortunate

comrade.

After steaming for a few hours, darkness fell,

making it difficult to see what the prisoners were doing. All forms of lighting were

prohibited at sea, so we were thankful that it never really got dark. We were

particularly warned to be on the look-out for E-boats, as the enemy were now

desperate to cut off supply lines to our forces established in Normandy. As it

turned out the crossing was uneventful.

It was sometime after dawn that the Sussex coast appeared as a

thin line on the horizon. When this was spotted by our reluctant passengers,

they began pointing and chattering amongst themselves. Then, about half the total number,

who were still wearing their helmets, took them off and with great gusto, threw

them as far as possible across the water, pausing to watch them sink.

When LCT 821 was some four miles off Newhaven, I sent one of my more

memorable signals to the harbour authorities informing them of our unusual

cargo. We were met by an assortment of army

officers, armed guards, policemen and pressmen. A crane was on hand to

lift off the wounded.

Once

unloaded, we set course for Portslade,

while attempting to restore LCT 821 to her former glory on the way. While hosing her

down, we discovered that our passengers had rid themselves of their personal

effects, such as pay-books, photos and letters etc., tucking them behind various

ship's fittings. We also cleared up an abandoned army bicycle with

a buckled wheel, which had generated great interest amongst the Germans. We

found a neatly wrapped package in green waterproof material strapped to the

carrier, which contained a dozen fully primed Mills hand grenades. There was

much speculation as to the outcome had the Germans been more inquisitive.

A few hours after arriving in Portslade, 821 was hauled out of the water

onto a slipway, especially constructed for landing craft casualties. It was operated on by

shipwrights brought down from Northern shipyards. In contrast to previous

occasions, leave was granted to the crew, my watch being the first to depart.

By a strange twist of fate, the following evening I was sitting in the cinema

of my home town watching the D-Day landings on newsreel, thinking that I was

the only one watching, who

had been in the thick of it!

I reported back aboard to free the other watch for their leave. It was

during this time I saw a strange flying object coming in quite low overhead

from a seaward direction. It was trailing

a ragged flame and emitting a distinctive chugging sound. As we gazed upwards in amazement, we were witnessing one of the first

"buzz bomb" attacks (also known as the V1).

Further

Crossings

Further

Crossings

With leave for both watches at an end,

821 was declared seaworthy, having

been re-plated and strengthened. We proceeded along Southampton town quay for another load to ferry to Normandy. This soon developed into a

routine with nightly crossings in small convoys, usually without escorts.

[Photo;

a scale model of HMLCT 821.]

On our second arrival off Normandy, we were forced to lie at anchor for several days

due to bad weather and sea conditions. The front line was now several miles

inland and during the hours of darkness the distant horizon was illuminated by

shell-explosions and fires. Closer by, from seaward, a continuous stream of tracer shells

indicated where enemy coastal forces, possibly E-boats, were attempting to

penetrate the protected anchorages. Our first visit had been to an

area just West of Ouistreham but this time the coast was mostly sand dunes and

rural farm land.

When we attempted to beach, strong winds took us broadside on and

heavy seas threw 821 against one of the enemies steel obstructions, resulting in a

badly holed diesel tank. We dried out on the sand but this time in more

peaceful surroundings. A naval repair party was close and they welded up the

holes with an acetylene torch - a tricky job considering the proximity of

diesel fumes.

We were re-floated

with the aid of a bulldozer and remained at anchor for a few more days to

await better weather conditions, during

which time I

celebrated my birthday on June 24. There was a poignant

reminder of the fortunes of war, when the body of a seaman, supported by his

lifebelt, floated along the side of the ship. He had been in the water for many days, drifting on

the tides. Perhaps my rum ration on this day, supplemented by that of my

shipmates, dulled my senses, since I don't recall feeling any sense of sadness.

Later in the summer,

as the better weather returned

and the front line receded, our ferrying trips became quite

pleasant, with football on the fine sandy beaches and strolls along the sand

dunes. On one peaceful sunny day, we were at anchor quite close to the shore,

with the mighty Battleship HMS Rodney at anchor in deeper water on the seaward

side. Without warning, the peace was shattered when an enemy shell came from

behind hills, which formed the skyline, and scored a direct hit on a church close to the

waters edge. Seconds later, Morse signals were being passed between Rodney and

a water tower protruding from the trees on the distant hills. Slowly, one of

Rodney’s 16 inch guns elevated and, with a mighty roar and searing flame,

replied in full, followed shortly by a second round. This was probably

one of the last actions involving the large guns of the Royal Navy, such as

those fitted to HMS Rodney and HMS Nelson. I felt privileged to have had a

ringside view of that brief encounter and thankful that HMS Rodney was at

hand.

As we notched up more and more channel crossings, the engines of 821 began to

feel the strain. We increasingly had to accept tows, especially in the latter

part of each trip, if the sea was choppy. On return journeys we

often carried damaged fighter aircraft, spitfires and hurricanes.

It was usual to sail from Southampton with a kite balloon (smaller than a

barrage balloon) moored to the guardrail by

the RAF and collected by them on the other side for further use. These

balloons provided an additional safeguard for us from overhead attacks during transit.

However, Sub Lieutenant Rae took a different view and, once out of sight of the

Isle of Wight, I would release the balloon and watch it disappear into the

clouds. Sometimes these balloons could be seen dropping into the sea as a

tangled mess having burst in the upper atmosphere. The CO believed that the

balloons would be spotted over a distance of some 30 miles, pinpointing our

position and more or less inviting the enemy to attack.

While casting off from a loading jetty near Gilkicker

Point, we lost one of our original crew members. Having loaded troops and their

vehicles, 821 was moving slowly astern with engines idling. One of the crew was

paying out a large manila rope with a loose turn around the bollard. The rope

caught around his ankle and he stumbled. As we moved slowly away from the jetty, he was pulled against the bollard, where his leg took the

full momentum of the ship. From my position on the bridge, I clearly heard his

leg snap as soldiers rushed forward to cut through the rope, an impossibility,

given that it was still paying out. Our shipmate was eventually taken ashore

in an unconscious state.

Several trips later on a return journey, and within sight of Spithead, one of

the main engines disintegrated when a connecting rod penetrated the sump

casing. We were directed to Cowes and moored some distance up

the River Medina. That proved to be my last voyage on LCT 821. A few days

later, I was on draft to HMS Scotia, a signal school on the Ayrshire coast, to

begin a course, hopefully, to become a Landing Craft Signalman II.

Postscript

The accommodation at HMS Scotia was

luxurious after my cramped life aboard LCT 821. To shower, instead of

washing out of a bucket of water heated on a galley stove, was a treat, as was stretching

out on a bed instead of coping with the restrictions of a hammock.

However, the greatest pleasure of all was undisturbed sleep instead of the

watch-keeping around the clock, whether at sea or in harbour.

The course was, for me, very much a refresher but with more

Morse by buzzer

and the use of much bigger signalling lamps. With a star above my crossed flags, I returned to Southampton but, this

time, I was based ashore at the flotilla offices in the new docks, standing in

as relief on various craft as and when required.

It was on one of these postings that the craft

I served on arrived at the Mulberry Harbour, where unloading was carried out at all stages of the tide. We

were away from the UK for several weeks. We received orders to proceed to a Liberty ship

riding at anchor in an isolated area away from all other shipping. There was

good reason for this as we soon discovered... there were faulty batches of shells and bombs amongst its

cargo! Alarmingly, we were to tie up alongside and take on the useable lots, the

rejects to be lowered onto a pontoon for dumping at sea. There was great

relief when, loading completed, we proceeded along the coast to Le Havre and tied up at the dockside.

We were able to do a spot of sightseeing in

what remained of the city and I especially remember an occasion when several

open-backed trucks passed along the street carrying German prisoners. The

looks and waves exchanged between the prisoners and old ladies watching from

the pavements gave

the impression of mother and son relationships

between many of them.

The Mulberry Harbour was now an area of

concentrated activity around the clock. Landing craft and ships of every size

continuously disgorged all types of vehicles and endless stores onto the

Bailey Bridge type piers. DUKW amphibians loaded up with supplies, proceeded

ashore, and onwards to the dumps

inland. Such was the volume of traffic running in endless columns that, from a

distance, it gave the

appearance of a giant ant colony on the move.

As the larger ports along the French coast became available for shipping, the

activity at the original beaches eased off. Eventually, we spent most of our

time at the Mulberry Harbour awaiting sailing orders. It was there we learned that the war in

Europe was over. Immediate shore leave was granted and

a DUKW came alongside

offering lifts to Bayeux. The amphibious DUKWs allowed us to travel

from the anchorage to a point several miles inland without having to change

transport. From Bayeux we hitched a lift in an army truck as far as Caen. We

returned to the Mulberry Harbour the following day in a similar manner. Shortly

after, our craft returned to England, where we moored on a

mudflat alongside Hythe Pier.

a DUKW came alongside

offering lifts to Bayeux. The amphibious DUKWs allowed us to travel

from the anchorage to a point several miles inland without having to change

transport. From Bayeux we hitched a lift in an army truck as far as Caen. We

returned to the Mulberry Harbour the following day in a similar manner. Shortly

after, our craft returned to England, where we moored on a

mudflat alongside Hythe Pier.

[Photo;

the author with models of Royal Navy craft from the

war years.]

There was a feeling

of anti-climax now, as one by one the crew was gradually drafted ashore. A

few, like myself, went to Portland Terrace, a large building in the centre

of Southampton. As my home was not too far away, I volunteered for guard duties, which enabled me to make

use of all my free time.

With more and more crews being brought ashore,

a large draft of us was moved to Westcliff on Sea in Essex,

where several streets of semi-detached houses had been cordoned off to form a

temporary naval barracks. There, we undertook a familiarization course on

mines, torpedoes and depth charges and, occasionally, games of cricket on a

neighbouring sports ground. For us the war had well and truly ended.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page

which can be purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose

search banner checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type

in or copy and paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for

book suggestions. There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no

passwords. Click 'Books'

for more information.

Correspondence

Gunner Pat McQuade who served on LCT

821 adds; "when LCT 821 was decommissioned we were ordered to sail to

Bordeaux and hand her over to the French authorities to be used to transport

timber up and down the river. When we left her for the last time we felt

glad within ourselves that our craft would be doing good for the town rather

than rusting

away somewhere in a scrap-yard, which to us,

would have been a sad end to a craft that had served us well. To this day

(29th May 2010) I still wonder how long it kept sailing on the river..."

glad within ourselves that our craft would be doing good for the town rather

than rusting

away somewhere in a scrap-yard, which to us,

would have been a sad end to a craft that had served us well. To this day

(29th May 2010) I still wonder how long it kept sailing on the river..."

[Photos; Pat in full colour and a

wonderful tongue in cheek family tribute to the man.]

Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing Craft

Association was advised of Pat's contact with this website. He informed Eric

Loseby who provided the information for this page and within a few days the

two RN veterans who served together on the same craft off D-Day's Normandy

beaches, were talking to each other for the first time in 66 years. They

intend to keep in touch.

Acknowledgments

This account of HMLCT 821 is based on the notes

of Signalman Eric

J. Loseby. They were transcribed by Tony Chapman, Archivist/Historian for the LST

and Landing Craft Association. It was further edited by Geoff Slee for presentation on

the website, including the addition of maps and photos.

the LST

and Landing Craft Association. It was further edited by Geoff Slee for presentation on

the website, including the addition of maps and photos.