|

Landing Craft

Tank (5) 2304

- LCT (5) 2304 on D Day.

UK

Combined Operations (Navy) Personnel & USA

Army Forces Bound for Utah Beach

%202008_small1.jpg)

Background

Two accounts of HM

LCT (5) 2304's passage to Normandy on D-Day

are presented here... one from UK crew member, Midshipman,

John Mewha and the other from passenger, US

Army Lieutenant, Ernest C James of Company A,

238 Engineer Combat

Battalion.

[Photo; US LCT(A)

2008 was the same type of landing craft as HM LCT (5)

2304. Photo taken on D-Day + 1 by which time her bow

ramp had been lost. US Army Signal Corps photo provided courtesy of

Navsource. For more information on 2008 click here].

John

Mewha often wondered what became of the men of the US

238

Engineering Combat Battalion (ECB)

he delivered to Utah beach on the morning of D-Day, June 6, 1944. Sixty one years

later, through the good offices of Tony Chapman,

archivist and historian of the LST & Landing Craft Association, J ohn Mewha was

reunited with former Lieutenant, Ernest C James of Company A of 238 Engineer

Combat Battalion. Under their commanding officer, Captain Richard Reichmann, the

men were shipped to Utah beach by LCT

(5) 2304. ohn Mewha was

reunited with former Lieutenant, Ernest C James of Company A of 238 Engineer

Combat Battalion. Under their commanding officer, Captain Richard Reichmann, the

men were shipped to Utah beach by LCT

(5) 2304.

[Photo; left Midshipman,

John Mewha RIP 17.2.08 -

port after stormy

seas].

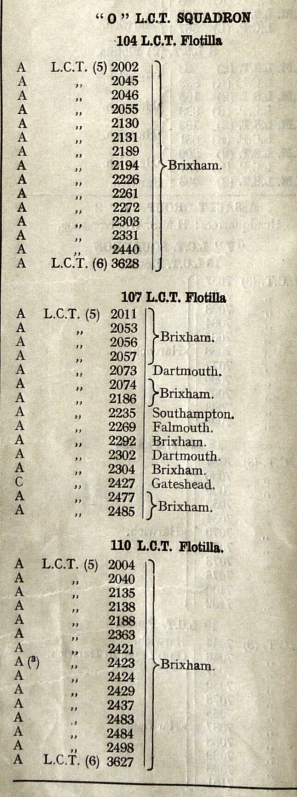

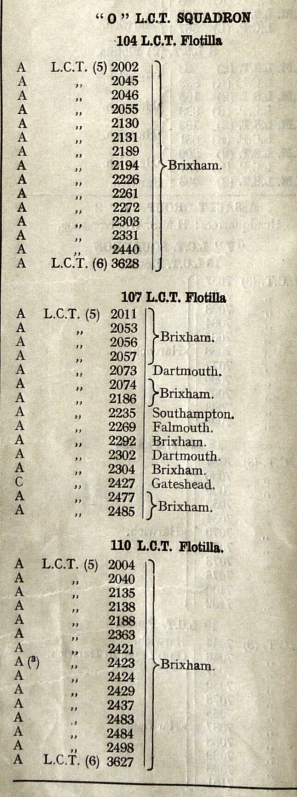

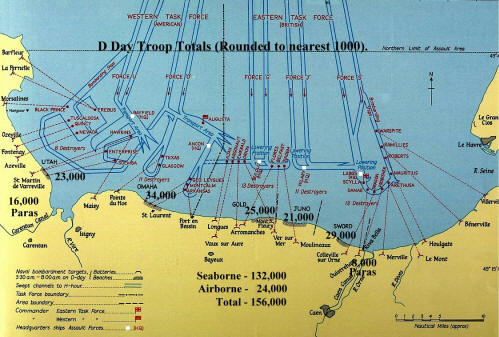

The planned order of beaching on Utah assigned seven British Mk5 LCTs to the US Army’s 238 ECB.

The craft involved were 2056 and 2057 with the men of Company A, 2477 and 2304

with the men of Company B and 2011, 2074 and 2302 with the men of Company C. We now know

that LCT 2331 was a late addition.

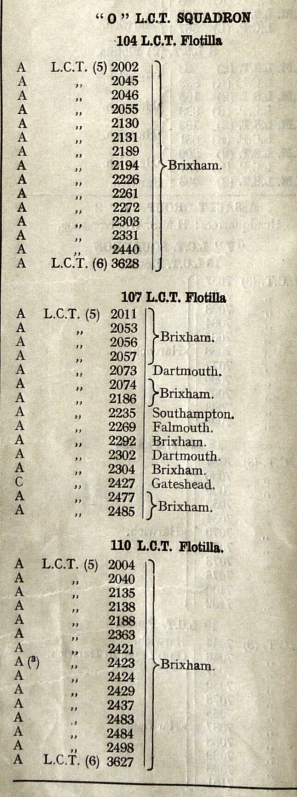

LCT 2304 was part of the Royal

Navy’s 107th Flotilla of ‘O’ LCT Squadron under the command of Lieutenant Commander Skrine. Midshipman, First Lieutenant, John Mewha

was just over 19 years old on D-Day - the same age as his counterpart

on LCT 2331, Midshipman George Boulton.

This is John Mewha's story.

Loading for D-Day

After our arrival in Brixham,

our fairly restful time was interrupted only by a

trip to Dartmouth, where we checked out 2304. According to my records, she was

built in the USA by the Omaha Steel Works (Sic), shipped across the

Atlantic in three sections on a Landing Ship Tank (LST) and assembled in the UK. Her class was the smallest tank landing craft in use at the time with

a capacity to carry a maximum of five tanks. The craft had

additional armoured plates and was re-designated as the Mark 5 LCT (A)...

'A' denoting armoured.

On or about the 31st May, we left Brixham and sailed across Torbay to the harbour at

Torquay. Our orders were to transport 70 American

Combat Engineers with their

vehicles and a medical team with their Jeep

to Utah beach. I have a copy of the boarding orders showing that the

detachment departed from Stover at 0135hours and expected to arrive in Torquay

at 0245hours. Loading commenced at 0300hours and I was responsible for the

safe stowing of vehicles and men on the craft. This was the occasion I first met

Ernest James.

The boarding documents show that Lieutenant James was C/L CO for

this operation. The secret embarkation personnel rosta,

which lists everyone we carried from Company A, also shows the medical detachment

– H/S Company – Engineer DUMP TRUCK company – 991st Engineer Treadway

Bridge Company and two members of 237th Headquarters Battalion. The

loading was successful and we returned to the harbour at Brixham, where we

anchored.

A False Start

On June 3rd, we left Brixham with other vessels and sailed to the

south of Start Point, where we waited for the convoy from

Plymouth, Salcombe and Dartmouth. This convoy was given the name 'Force U' and

was to land on the eastern side of the Cherbourg Peninsula in an area

code named UTAH.

The convoy made its way to the south of the Isle of Wight,

which we reached late on 04 June. We started the journey across the English

Channel to Normandy but, during the night, we turned round because of the appalling

weather and were escorted by cruisers into Weymouth

Bay. This part of the

voyage was completed without either lights or radio and no anchorage was

available, so we circled for several hours in very rough sea conditions. This

period was probably the most dangerous – there were many collisions and

explosions.

The

Real Thing

Later on 05 June,

we regained our position in the convoy and once more headed for Normandy.

During the night I came off the bridge and saw an Officer sitting in our

crew’s mess deck writing a diary of events. Was that Lieutenant James

I wonder? I can

recall having a drink with him and Captain Reichmann in our little wardroom.

We greatly admired

the fortitude of our passengers. They had been on board several days and nights

with little protection from the elements and totally

inadequate sanitary facilities. It was no easier for my crew, who worked hard

under similar conditions and were very supportive. When dawn broke we could not

believe our eyes; the whole sea was covered in ships of all shapes and sizes...

a sight never forgotten.

On reaching the holding area off Utah

beach we proceeded

directly to the beach with three other British manned landing craft.

We sailed under the guns of several

battleships, which opened fire on targets ashore as we passed by. The noise was deafening. The

noise intensified as salvos of explosive

rockets, sequentially launched from LCT (R) craft, joined in the melee.

We followed a marked

channel and on reaching

the beach area discovered the initial landing was a

thousand yards away from the planned site. Despite searching for a

clear way into the beach avoiding

wooden stake beach obstacles embedded in the

sands, we had little success. Under increasing

pressure and in less than favourable circumstances, Lieutenant Rankin

decided to drop our kedge anchor and

go

in regardless. We sustained some damage to the craft and hit a

concealed sandbank some yards from

the shore line. The landing ramp was unable to reach the beach, resulting in a drop of

several feet from the ramp into the water for the disembarking men and machines.

Disembarkation Disembarkation

My duty

at this time was to lower the ramp and

oversee the disembarkation of our cargo. As the ramp

door was lowered, it became

clear the craft’s

bow was not square to the beach, due to the rough sea conditions, unpredictable currents and wind.

To rectify this I, and one of my crew, secured ropes to the forward

bollards, took them on to the sandbank and tried to hold the

craft’s head steady. I have no idea if our efforts did any good but all the

while the noise of enemy shelling around us was deafening. The landing craft next to us was badly damaged.

[Right, an extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' showing the

disposition of LCT (5) 2304 just prior to D-Day].

I have no clear memory of the order of

disembarkation... vehicles or men. Lieutenant James reminded me that to assist

the vehicles from the lowered ramp onto the beach a bulldozer winched all the vehicles

over the offending gap. The men were, understandably,

reluctant to jump into several feet of water and Captain Reichmann used all his

influence to 'persuade' them to go ashore. We were keen to return to the holding

area and to embark more vehicles and men from the larger Landing Ship Tanks

(LSTs) and merchant ships positioned some miles off the landing beach. We

had sustained some damage but fortunately none to our engine room,

so we were still operational.

The

Resurrection!

We sailed to a marked channel, where a US Navy Landing Craft Infantry (Large) [LCI

(L)],

immediately in front of us, disintegrated as a result of a shell or mine. We reached the holding area safely and reported our damage.

We were holed in several places by the underwater obstacles and were advised

that our 'craft was expendable.' We were to await further orders concerning our

evacuation before our craft was sunk. We had become rather attached to our landing

craft, since it had

been our home for at least nine months and, against orders, we moved to an anchorage

some distance from the holding area.

We were

exhausted through lack of sleep and nervous anticipation of

the day's events.

Despite this, at dusk we slipped away from the anchorage and made our way to

Southampton on our own. This was an adventurous night for us, since we

were aware that German E-boats were patrolling the

area looking for the likes of us. However, our luck held and we arrived safely

in Southampton, where the damage was assessed. We were made to feel very welcome

especially by the dock workers. After repairs were completed, we returned to Utah

beach with another load of equipment and men and then we proceeded to the

British Gold beach, where we unloaded larger merchant ships in and

around the Mulberry Harbour at Arromanche.

When attending the 40th anniversary

at Arromanche with my older son, we approached a man standing on his own

a few yards away on the promenade. He had been a Free French pilot

and leader of a group that laid the smoke on the beach as we were approaching.

It was the first time he had attended one of these ceremonies and he had

brought with him copies of his flight plans etc. He told us that we were the

only people who had spoken to him during the day. When attending the 40th anniversary

at Arromanche with my older son, we approached a man standing on his own

a few yards away on the promenade. He had been a Free French pilot

and leader of a group that laid the smoke on the beach as we were approaching.

It was the first time he had attended one of these ceremonies and he had

brought with him copies of his flight plans etc. He told us that we were the

only people who had spoken to him during the day.

[Photo;

John Mewha talking to Her Majesty the Queen

on 1st Aug 2004. Photo courtesy of the Daily Echo, Bournemouth.)]

I am delighted to have been reunited with Ernest James after all this time

and this is largely due to the efforts of Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing

Craft Association of which I am a member.

In more recent times I have had the opportunity to confirm that I loaded the 238th Company from a ramp in the

inner harbour of Torquay. Local people were most surprised, believing that the

loading had been confined to American built 'hards.' No

one in the town had known that we used the inner harbour and no doubt a plaque commemorating this is now in place.

If

not, it should be!

D

DAY ON HM LCT (5) 2304

UK & USA Forces Working

Together

%202008_small1.jpg) These are the recollections of US Army Lieutenant,

Ernest C James of Company A, 238 Engineer Combat Battalion. These are the recollections of US Army Lieutenant,

Ernest C James of Company A, 238 Engineer Combat Battalion.

On June 5th-6th, 1944, he was aboard

the Mk5 HM LCT 2304 of the 107th Flotilla of O LCT

Squadron making her way to Utah beach in support of the US 4th Infantry

Division. His writings here are reproduced with his permission

[Photo; US LCT(A)

2008 was the same type of landing craft as HM LCT (5)

2304. Photo taken on D-Day + 1 by which time her bow

ramp had been lost. US Army Signal Corps photo provided courtesy of

Navsource. For more information on 2008 click here].

Crossing the Channel

We loaded our vehicles in late May and early June. All trucks

carried twice their normal load, about seven and a half tons, including several

tons of explosives on each truck. All available space was filled with extra

equipment, which we were instructed to dump on the beach on landing, thus getting

replacement materials to the beachhead. On arriving at Torquay, our trucks and invasion equipment were loaded on LCTs and then we waited. Sleeping space was

found in the open boats, usually under the canvas tarp covering of our trucks. The LCT was moored for four days in the harbour, waiting, while troops ate K rations

(cold food) and wondered when we would leave.

Our portion of the invasion fleet departed Torquay and was scheduled to hit

the beaches on the morning of June 5. As it left, two boats collided and burned

in the water, making a perfect beacon for German planes. By this time the Allies

had air superiority so there were no attacks. The weather on June 4 was foul, so

our boats pulled into Weymouth harbour that evening... D-Day was delayed a day.

By this time most men were deathly seasick and many ships and troops were left

behind due to mechanical trouble.

At dawn, our invasion fleet left the harbour, and soon after our LCT sprang a

leak. The British Captain told us that he couldn't get the bilge pumps started.

Lt Knapp, our motor officer, pulled out our water supply units to pump the

bilge but we calculated we would probably sink on the morning of the sixth.

We succeeded in keeping the LCT afloat until dawn on June 6th, when it appeared

that we may not remain afloat. Thoroughly soaked, our 'gas proof' clothes made us

even more uncomfortable. The LCT Captain, sensing our dilemma, invited

Reichmann, Knapp and I into his cabin to share a small draught of his precious

rum.

We couldn't help feeling a thrill as a destroyer pulled alongside and the

Captain yelled to us that June 6th was D-Day and 0630 was H-Hour. From that time,

we had a single sense of purpose as the landing craft headed for France and the

beaches of Normandy. Knowing it was a matter of hours before we would enter

combat for the first time, this last night was spent anxiously awaiting our

uncertain future. Only the more hardened souls and those worn out by prolonged

bouts of sea-sickness managed to sleep.

Just after midnight on the 6th, the drone of hundreds of planes was heard

above the noise of the LCT's engines. Crawling from under our protective tarps

into the biting wind, we saw the signs of war on the horizon. The sky to the east

was lit up and the shadows of planes carrying paratroopers floated ominously

overhead. Battleships, cruisers and destroyers were pounding the coast and

bombers were giving inland installations a pre-landing drubbing. Long lines of

flares dropped though the overhanging clouds and the sky appeared like a

gigantic illuminated Niagara Falls. Needless to say there was no more sleep that

night. No matter, it was a spectacular, but deadly show!

D

Day

When dawn broke, an unbelievable scene of thousands of boats circling and

heading in to the beach created a panorama never before seen. Infantry climbed

down nets from troop carriers into small boats and groups of these boats were

circling, while waiting orders to peel off and hit the beach. A nearby destroyer

hit a mine and sank and we saw other boats rescuing sailors tossed into the sea.

Orders to move in towards the beach came from loud speakers on private British

yachts, which had been converted for this purpose.

Because we were in danger of

sinking, we were given permission to proceed to the beach without delay. Our LCT

headed for a line of buoys leading to shore and landed at about 0700 - an hour

and a half before our scheduled time. Thus we were the first of the 238th to

land in Normandy.

While making our run into Utah Beach, the battleship Texas fired salvo

after salvo over our heads. 16 inch projectiles could be seen flying through the

air and hitting their targets in a resounding blast. Our LCT had only a few

inches of freeboard and while approaching the beach at high speed, our bow

high and stern low, we hit bottom many yards out. German 88mm shells hit the

landing area around us creating geysers in the rough seas. It was a baptism of

fire. We should have been able to drive our equipment and trucks directly off

the boat onto the beach but we were floundering in several feet of water.

Reichmann and I jumped in, inflated our Mae Wests, and swam to the shore with

several others. Seeing many couldn't swim, we both removed our outer clothes,

swam back to the LCT and helped those who were stranded to reach the shore. I

received a Bronze Star for this action, but due to an unfortunate circumstance,

described later, Reichmann did not receive any recognition. Reichmann and I jumped in, inflated our Mae Wests, and swam to the shore with

several others. Seeing many couldn't swim, we both removed our outer clothes,

swam back to the LCT and helped those who were stranded to reach the shore. I

received a Bronze Star for this action, but due to an unfortunate circumstance,

described later, Reichmann did not receive any recognition.

[Photo; an extract from the

Admiralty's 'Green List' showing the disposition of LCT (5) 2304 just prior to

D-Day].

A young bulldozer operator volunteered to drive his dozer off the LCT ramp

into several feet of water and on to the beach. There he was, a head, an exhaust

pipe and an air intake moving through water as 88mm shells

blasted around him. When the dozer reached the beach,

he winched the truck, already loaded with troops, off the LCI and on to the

shore. This way we got all seven vehicles on

to the beach without losing one. To our knowledge the LCT never made it back to

England.

The shoreline consisted of a long, shallow beach with sand dunes above the

water line. Behind this was a road and then a few miles of swamp lands criss-crossed

with canals. There were several causeways leading from the beach to the hedgerow

fields and farms beyond. The swamp was flooded as tide gates had been opened by

the Germans to obstruct the Allied advance into the hinterland.

While in the process of landing and breaking

through the sea wall, we were under fire from nearby artillery and pill boxes on

the beach. Engineers, with satchel charges and flame throwers, quickly

decommissioned the emplacement. (In 1979, I took photos of those pillboxes, while

on a trip following my wartime routes.)

Shortly after landing, I had the first of many lucky escapes. I was

standing beside a truck loaded with tons of explosives when an 88mm shell

exploded a few

yards away. Plover, the truck driver, was knocked out and later

evacuated. The next shell hit the truck but it was a dud... it had hit a primed satchel charge but the

nitro-starch had not exploded. The truck tyres were blown and the body peppered

with shrapnel. There was not enough brown paper in our K-rations to clean us!

By about 1030, most of the battalion had landed on Utah Beach and were on their

way to our immediate objective, an assembly area. While walking along the road

parallel to the beach, we soon came under a barrage of 88's. Reichmann and I

ordered our men into the ditches and we crawled through an intersection. We saw

a group of infantry men standing up, wondering what to do. I yelled for them to

take cover but too late - an 88 hit in their midst. Seven

men died, because they didn't know how to protect themselves. We learned from our

training! Shortly after arriving at the assembly area, we saw 4th Division

Infantry men advance across the swamps chasing after retreating Germans. We had

received our baptism of fire on land!

Other than amphibious tanks, our trucks were among the first vehicles to land in

France. We were attached to the 4th Division and our first mission was to open

several roads from the beach to the high ground about a mile away. Most of this

area was covered by swamps and creeks with many causeways under water

and all bridges were blown up by the enemy.

Fortunately for us, the German garrisons in the area were less experienced,

because their Command did not expect a landing adjacent to flooded marshy

ground. On the other hand, our intelligence, good as it often was, failed to

recognize the ease with which the Germans could flood the area. Tide gates were

normally closed at high tide and opened at low tide to drain the swamps.

Reversing this process, the Germans easily flooded the area. Hundreds of casualties resulted from this snafu

(error) in intelligence.

Mongol soldiers captured on the Russian front were placed in these positions

by the Germans. Enemy artillery, and to a lesser extent their air force, gave the

beaches a terrific pounding, especially a day or two after the landing. By this

time we were miles inland. Our air and navy bombardments pounded their positions

so hard that many German troops withdrew, leaving the beachhead to us. One Nazi

strong point on the coast towards Cherbourg held out and kept shelling us for

several days.

By 1435 hours on D-Day, Company B had opened road U-5 to the high ground.

Tanks and artillery poured through this road and long before Utah Beach

was secured. This road required a 30' steel tread-way bridge, which was under

artillery and small arms fire. It was the first bridge built in France on D-Day. When

Company B men completed the bridge, the first tank was hit by an 88mm shell as it

reached the middle but the momentum carried it over to the other side. Our tanks blasted the German tank which fired the shell and

the bridge stayed intact.

T/5 Alton Aldman Ray of Company C, received the Croix de Guerre for his heroic

action in evacuating wounded infantrymen. The entire Battalion had no casualties

that day, due in part to the excellence of our training in the past year. During the entire day

of June 6, the Battalion was engaged in clearing assembly areas of mines,

repairing roads, clearing the beach access, building bridges and draining the

swamps in order to use the causeways.

Late that afternoon, as we worked on access roads, we heard the distant

drone of aircraft. Looking seaward, we saw a huge armada of fighter planes leading C-47s,

which passed above us as they dropped gliders and paratroopers over our heads.

We could see enemy tracers passing through both and the gliders crashing as they

landed. These were the much needed

reinforcements for the first air drops. Many of the planes and gliders blew up in the

air... it was a carnage but the reinforcements saved the day.

That night we moved into a bivouac area at Hebert but most of us worked

on. By daylight, and by using any materials which were at hand, Company A had opened a return causeway, which had been entirely under water. Company B had

secured

the outgoing causeway and these were the only beach accesses for days and were

vital to the Allies. The

going was rough in these early hours for engineers, paratroops, infantry and the light tanks

which had

landed. There was, as yet, little in the way of artillery or support troops.

My brother-in law, Ralph Fell, had

been a Sergeant in WWI in France. He wrote several letters, which hit at the

heart of what we were experiencing. One such was written to my sister Edith on

D-Day. He suspected that I was on

the landing.

JUNE 6, 1944. Lincoln Nebraska. EDITH: Today is the day. I think everybody

should say a prayer for the success of our army. I think they have the same

feeling I had in 1918 when we landed in France. Chateau Thierry had just been

fought and the Germans had made their last bid for Paris. We knew the tide had

turned, and what we were in for.----RALPH

Army records of the day's events showed that;

• Sunrise on June 6, 1944 was at 0558 and H-Hour was at 0630

• The 238th Combat Engineers landed from 0700 to 1100 on D-Day. Most landed

in the first hour.

• The total force of the landing was about 24000 men, of which 16000 were

American and 8000 were British.

• 1000 aircraft took part, landing the 81st and 101st Airborne behind Omaha

and Utah beaches and the British 6th Airborne around Caen near the Orme River.

The Americans were scattered, but each small group organized when they met, and

created confusion and fear in the German troops.

• By nightfall, the 4th Division and Airborne were 6 miles inland from Utah

Beach.

• The Airborne had about 2500 casualties (15%) and the 4th Division had 197

casualties.

Two LCTs with 238th personnel had engine trouble and returned to port on

June 5. On one was the Battalion CO, Col. McMillian, so Major Martin Massoglia

assumed command of the Battalion on D-Day. Other than these two LCT's, one

sunk in Southampton harbour before it could be unloaded.

There were no casualties on D-Day. However,

weeks later, Lt Chalfaunt claimed a Purple Heart for a piece

of shrapnel, which hit him while he was watching a dog fight on the beach! We had

been in the midst of the full action all day and night. Our training paid off! For a few days we bivouacked at Hebert. Records are incomplete of other

bivouacs until 06-12-1944. Mostly we slept where we were working.

Secret

Embarkation Roster

Note: LCT 197 (see below) was the army serial, or loading number, for

HMLCT 2304. It was this number, rather than the craft number, that those going

aboard looked for at the point of embarkation.

SECRET

U.S. ARMY EMBARKATION PERSONNEL ROSTER LCT 197.

Co.A 238 Engr.Combat Bn. 45106 Station. Torquay

SERIAL NO. NAME AND

GRADE

01101177 Reichmann, Richard

S. Capt.

01103235 James, Ernest C. 1st

Lt

20318192 Freck, Frank R. S SG

35492027 Hedrick, Paul F. S SG

38339724 Hewton, Thomas G. S SG

20107649

deleted Smolkowicz, Joseph J. S SG

34357945 Creel, Joseph E.

SGT

34586226 Davis. Marion P. SGT

34525304 Shavers, Lee A. SGT

34587501 Swanner, Frank A. SGT

34596771 Rollins, Jackson W.

TEC4

38139355

Late addition Harrison, Jack (NMI)

11048179 Fiore, Amollo A.

CPL

33567309 Gelnett, Lawrence E.

CPL

38393065 Atkins, Everett C. TEC5

33628466 Blevins, Herman L. TEC5

38393029 Long, Dwight L. TEC5

33112901 Potter, Jack TEC5 ((Photo)

34524393 Wales, Bennie H. TEC5

34998346 Ward, Edgar T. TEC5

34579466 Brooks, Samuel E. PFC

34502420 Bryant, Johnnie O. PFC

33417839 Kelly, Jesse L. PFC

38393016 Mills, Harold W. PFC

33408231 Mistretta, Joseph J.

PFC

34524420 Morgan, Charles C. PFC

34407155

deleted Michels, Laurius PFC

34581588 Reid, Amburst H.

PFC

33143321 Venture, Joseph M. PFC

38217016 Vielma, Trinidad F. PFC

34595552 Simpson, Haywood L. PFC

33628233

Late addition Shephard, Raymond C. PVT

31037196 Bewes, Frank R.

PVT

34579603 Brown, James H. PVT

33534787 Calvert, Charlie M. PVT

34578444 Castleberry, Buddie PVT

38417662 Donaldson, William. PVT

33476306 Elliott, Freddie PVT

13068287 Fink, Telford N. PVT

33413811 Griffin, Richard L. PVT

33458584 Jelinski, Edward F. PVT

37530377 Jones, Earnest E. PVT

35803278 Jones, George B. PVT

34597967

Late addition Wilson, Nesbit C. PVT

38393727 Maxey, Clark D.

PVT

36758189 Piekara, Walter S. PVT

33476335 Plover, Joseph J. PVT

34578663 Self, James J. PVT

35872446 Spencer, Homer V. PVT

34536960 William, Charlie M. PVT

Med. Det. 238th Engr. Combat Bn 45127 LCT 197

0507298 Allinson,

Sydney M. CAPT

34525343 Emerson, Rufus B. CPL

34502128 McClure, Romio R. Jr

TEC5

34502128 Rawls, William K. TEC5

H/S Co. 238th Engr. Combat Bn. 45122

LCT 197

0468491 Knapp, Henry

D. 1LTW21311282 Jackson, Thomas T. WOJG

33408261 Buynak, John TEC5

34595179 Crouse, Carl R. TEC5

34539892 Hicks, Ernest R. TEC5

34540255

Late addition Marden, Lewis C. PVT

582nd Engr. Dump Truck Co. 46055 LCT 197 Station:- Newton Abbot.

35801584 Adams, Edward SGT

34675683 Ballard, Guilford TEC5

34654537 Bamberg, Albert N. PFC

34673678 Lewis, Willie H. PFC

34673647 Lewis, Clifton Jr. PFC

34246252 Strickland, Ralph W.

CPL

991st Engr. Treadway Bridge Co. 44454 Station:- Shiphay, Devonshire

32245559 Pesci, Dino V. TEC5

38337555 Howard, Malcolm J. PVT

34192304 Braden, Julian E. TEC5

36054081 Luachtefeld, Leo J. SGT

HQ. 237th Engr. Combat Bn.

LCT 197 Station:- Newton Abbot

Prepared by 1106th Engr. Combat Group.

32600466 Maggitti, Edward V.

T/SGT

32485217 Carrow, James W. TEC5

US LCT (A) 2008

is the same class and type as LCT 2304. On arrival in England, 2008 was assigned

to the Royal Navy under Lease-Lend. On November 21st, 1943, she was at Kings Lynn,

Norfolk, England, where 19 year old leading motor mechanic Thomas Harding C/KX

143840 fell overboard and was tragically drowned. He rests in Kings

Lynn cemetery close by. Prior to the invasion of Normandy, 2008 was transferred

back to the US Navy under Lease-Lend in reverse. On June 6th, 1944, she was under

the command of Ensign Ray Cluster USN as part of the Commander Gunfire Support

Group. She was assigned to the western flank of Fox Green sector of Omaha beach

with tanks of Company C of the US Army's 741st Tank Battalion and was due to

land at H hour. The photo was taken on June 7th, 1944, minus her bow ramp, lost on

the Normandy beaches the day before. A new ramp was fitted after delivering the

troops seen in the photo. She remained in service until the 'Great Storm' of

June 19th-22nd, 1944, when she sustained severe damage and was stranded on the

beaches.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Acknowledgments

These

two accounts of HMLCT 2304's passage to Normandy on D-Day were compiled by Tony Chapman, Archivist/Historian for the LST and Landing Craft

Association from the combined recollections of Midshipman John Mewha of the MK5

HMLCT 2304 and First Lieutenant Ernest C James of Company A 238 Engineer Combat

Battalion. In both cases the texts were edited for presentation on the Combined

Operations website by Geoff Slee

|

%202008_small1.jpg)

Disembarkation

Disembarkation