|

Landing

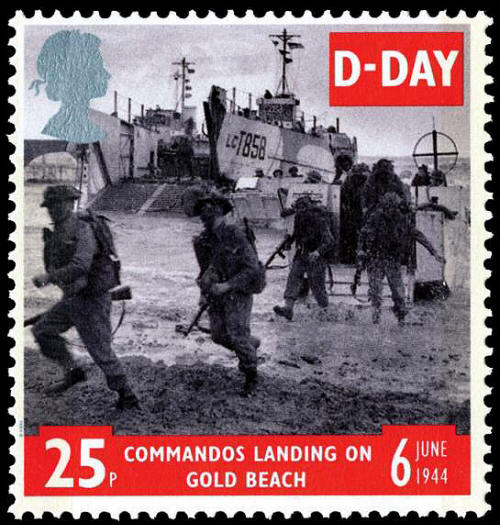

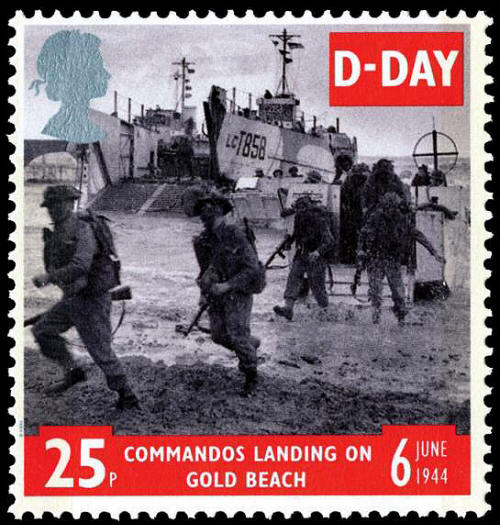

Craft Tank 858 - Immortalised in a Postage Stamp

By Lt Cdr H L Hurley

Training Training

I joined LCT 858 in September 1943 as First

Lieutenant. After initial sea-craft training in navigation,

signals and manoeuvres, we concentrated on amphibious landings onto

unimproved, sand, pebble and stone beaches by beaching and un-beaching

until the complex procedures became 2nd nature. We also practiced on concrete

'hards', which were ramps for loading tanks, lorries, jeeps, troop

carriers etc directly onto landing craft.

Typically, we

embarked our troops and their equipment from a beach or hard, manoeuvred

several miles along the coast to disembark them onto a different beach.

This procedure was endlessly repeated until we were heartily sick of it,

but we did become much more efficient and capable, when we were deemed ready for the final stage

of the training for the

coming invasion, which later became known as D Day.

There were thousands of landing craft of

many different types, each with their own jobs to do. Our role was to

embark self propelled (SP) artillery guns, which were mounted on open tank chassis

with the capability to fire 25 pound shells and the speed to quickly

traverse rough terrain to wherever they were needed. These formidable guns

were heavier and more powerful than their tank counterparts and they

became the main artillery support

for the invading army.

The SP guns

also had a less orthodox role as they

approached the landing beaches on their LCTs... they would fire

on beach targets from their craft's tank deck. This was our hazardous task

as part of the initial assault phase on D Day, when the full might of the

enemy's defences were largely intact. We approached our designated

training landing

beach ahead of the initial assault troops to “soften up” the imaginary

German defences. As the guns fired, they created a “creeping barrage” that

moved up the beach as our LCT moved forwards. The SP guns

also had a less orthodox role as they

approached the landing beaches on their LCTs... they would fire

on beach targets from their craft's tank deck. This was our hazardous task

as part of the initial assault phase on D Day, when the full might of the

enemy's defences were largely intact. We approached our designated

training landing

beach ahead of the initial assault troops to “soften up” the imaginary

German defences. As the guns fired, they created a “creeping barrage” that

moved up the beach as our LCT moved forwards.

[Photo; The author on the occasion of his

DSC award ceremony in 1945].

Each LCT flotilla typically comprised 12 landing craft,

which formed line abreast as they approached their landing beach. The

first wave was followed by another 12 landing craft, each carrying 4

SP guns - 96 guns in all that fired sequentially to ensure the maximum

damage, alarm and confusion amongst the defenders. Two further flotillas followed behind

us, saturating the landing beach area before the first troops landed. This

proved to be a very accurate and effective method of shelling. As each

flotilla reached 500 yards off the beach they turned to port (left) and

headed back out to sea, to take up position behind the last flotilla,

ready to return to the landing beach again, but this time to land their troops

and equipment.

We had, by then, a good grasp of the

theory as described above but rehearsals started again to hone our skills

loading tanks from the hards at Southampton, sailing down the Solent

towards Poole Harbour, where we lined up in divisions before we approached Studlands

Bay. Guns commenced firing into the target area behind Studland. As

planned, we

duly turned to allow the next flotilla to fire their guns and then

followed in their wake to land our tanks, before un-beaching and heading

back out to sea to allow the next flotilla to land their tanks.

Preparations for D Day.

These complex procedures required

meticulous timing to avoid confusion and were practiced day after day up to the middle of May

1944. During the second half of May, all the

landing craft were examined to ensure they were fit for the gruelling task

that lay just a few weeks ahead. All stores were embarked including emergency provisions, ammunition for

our 30mm Oerlikon Anti-Aircraft guns, rifles, pistols and Lanchester

submachine guns. We were given navigational charts of the French coast and

our English Channel charts were updated with the latest possible

information. Meanwhile, the ship's officers were

briefed by all manner of authorities, fleet and squadron flotillas. As far

as possible, nothing was left to chance and the landing craft were all secured to

the quays of the “New Docks” in Southampton, in

“trots”

of 6 craft deep, over half a mile long.

Towards the end of May, a rumour

spread that HM the King would inspect our flotilla, which turned out to be

true, but the only people who saw him were aboard the outermost craft. The

Royal Barge for the King's visit down Solent Water and the River Test was

a small landing craft that was dwarfed by our LCTs. Security was intense,

so very few people knew of his visit in advance. It was good for morale. A “dit” (story) went around that the

visit was so secret that no Royal Standard was available, so an enterprising

Yeoman of Signals hastily made up a flag using mustard to simulate gold on

the standard. Perhaps it was only a story, but it did sound good at the

time and cheered us all up.

On the weekend of June 2nd

/ 3rd,

all shore leave was cancelled

and we embarked our troops and tanks on the Friday and Saturday, then

we sailed out into the Solent where we anchored. The whole of the Solent

between the mainland and the Isle of Wight was filled with loaded landing

craft, all in the precise order for beaching. On the weekend of June 2nd

/ 3rd,

all shore leave was cancelled

and we embarked our troops and tanks on the Friday and Saturday, then

we sailed out into the Solent where we anchored. The whole of the Solent

between the mainland and the Isle of Wight was filled with loaded landing

craft, all in the precise order for beaching.

[Photo; LCT 858 off a Normandy landing

beach].

We had been training with the same

troops all the time and became good friends with them, so decided to send

them ashore as best we could. We (illegally) hoarded tots of rum until we had enough to give each of the troops on

board a tot before they went ashore, and we saved rations to make an

enormous “pot mess”, a giant stew mixture, to ensure they had a hot

nourishing meal before they disembarked into an uncertain future. However,

on June 4th

the weather deteriorated and the whole invasion was postponed by 24 hours.

With a slight improvement in the weather, we set sail for France around 8pm on the 5th

June.

D

Day - the landings

We were led from UK waters by a flotilla of

minesweepers that cleared and buoyed a safe channel for us as

we approached the French coast. Accompanying us were large LST’s (landing ships

tank), which carried large numbers of tanks, lorries and supplies not

unlike a roll on roll off ferry. They also carried smaller landing craft (LCP’s

– Landing Craft Personnel) suspended by ropes attached to davits. They

were lowered into the water several miles offshore, fully loaded with

troops. During the initial assault phase they would have carried Army

Commandos and RN Beach Commandos, who

organised the landing beaches to receive men and equipment in an

efficient, well planned and orderly manner using a

bulldozer if necessary to remove stranded tanks or to push landing craft back off the beach into the

sea. They had to keep the beaches cleared

As we approached the beachhead, our participation in the initial barrage

started in accordance with the carefully planned programme. We then turned

outwards to allow the next wave to carry out their barrage, before heading

back to the beach to land our troops and their guns. As we approached the

landing beach at a distance of 200 yards,

our

“Kedge” anchor was dropped from the stern of the craft as it continued

towards the shore. The tension in the cable steadied the craft by reducing

the risk of it turning sideways and “broaching”

on the beach as a result of unfavourable winds and tides. It also served

to assist the engines in pulling the craft back

off the beach with the anchor winch after disembarking the troops and tanks. our

“Kedge” anchor was dropped from the stern of the craft as it continued

towards the shore. The tension in the cable steadied the craft by reducing

the risk of it turning sideways and “broaching”

on the beach as a result of unfavourable winds and tides. It also served

to assist the engines in pulling the craft back

off the beach with the anchor winch after disembarking the troops and tanks.

[Photo; A D Day view from the bridge of LCT

858 off the Normandy beaches].

Unfortunately, at

the time of landing, the water was choppy and the winds quite troublesome

so the kedge anchors were not holding some craft

steady as intended. Many smaller landing craft, which arrived later than

planned due to the poor weather conditions, dragged their anchors

resulting in numerous crossed anchor lines all tangled up with those of the

larger craft, which resulted in a real “bunch of knitting”. This left the craft

concerned in a vulnerable position open to hostile fire from the enemy's

entrenched beach defences including beach obstacles, land mines and anti- personnel mines (bottles

filled with explosives), which detonated on impact with landing craft and

vehicles as they landed. Many of the larger landing craft sustained damage

while many smaller landing craft were destroyed or seriously damaged

causing heavy casualties.

LCT 858 hit several mines on its bow and

stern during its first beach landing. Whilst we were on the

beach, two men in

duffel coats, steel helmets, lifejackets and sea boots

asked if we could take them to the

headquarters ship “Bulolo”,

which was directing operations from several miles offshore. The LCP, due

to transport them, had been blown up. It turned out that one of the men was Howard Marshall, a famous BBC War Correspondent

and commentator, who was covering the landings and had to get back to Bulolo to transmit his report to London for the evening news... no doubt

one of the most important broadcasts of WW2. duffel coats, steel helmets, lifejackets and sea boots

asked if we could take them to the

headquarters ship “Bulolo”,

which was directing operations from several miles offshore. The LCP, due

to transport them, had been blown up. It turned out that one of the men was Howard Marshall, a famous BBC War Correspondent

and commentator, who was covering the landings and had to get back to Bulolo to transmit his report to London for the evening news... no doubt

one of the most important broadcasts of WW2.

[Photo; Mine damage to the bow of LCT 858].

We took them on board but, while

attempting to pull back off the beach, we lost our kedge anchor when its

line

was cut to free the craft from the snarled up lines of other craft. Once off the beach, we examined

the damage sustained in landing, which included a hole by the ramp door

caused by a beach mine. (This damage can be seen on the postage stamp at

the front of the ship just above the water line and below the ship's

pennant number). This damage prevented the door from being secured with

the risk of it dropping down at any time. However, with the hole now above

the waterline, after the disembarkation of the tanks, there was no risk of

flooding.

Other damage included a small hole

in the engine room, which was easily repaired by

hammering a wooden plug into the hole. Another mine restricted the rudder's

movement, which removed the craft's ability to turn to the left. The starboard

engine was also damaged and in need of repair. Due to these difficulties,

other travel arrangements were made for Howard

Marshall and his companion. Later, we were amused to learn that he had

included in his broadcast details of his transfer from our ship because it

had been “mined, holed in 2 places,

engines broken, rudderless and sinking”. Apart from all that, we were ok.

Whilst all this was going on, the First

Lieutenant went over the side in a life vest into the sea to try to rescue

soldiers seen floating in the water. Unfortunately, each time, the soldier

was found to be dead and the bodies were quickly swept away by the sea. Whilst all this was going on, the First

Lieutenant went over the side in a life vest into the sea to try to rescue

soldiers seen floating in the water. Unfortunately, each time, the soldier

was found to be dead and the bodies were quickly swept away by the sea.

[Photo; Lt Cdr Hurley's war and service

medals, including the Distinguished

Service Cross, DSC, (left of photo) which he was awarded for the action

he so modestly describes above. He placed himself in immediate danger as

the enemy were shooting at soldiers in the water. The DSC recognises an

act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the

enemy at sea”... just below the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross and

Victoria Cross].

Return to Blighty (England)

We tried all day to manoeuvre the

landing craft just using the remaining engine, but to no avail as the

damaged rudder made it impossible to steer a direct course. We had drifted

away from the main beach and were still being carried by the

tide. As we had lost our main anchor, we tried to halt our drift using a

lightweight “standby” anchor, but it was too light to hold the ship. We shackled it to a large number of

Tank straps, heavy

40lb chains used to tie the tanks down on the ship's deck. The extra

weight gave the anchor the bite needed to stop the ship drifting. We had

no option but to wait for the wind to drop.

Night came and so did the German

planes, dive bombing any ships they could find. Unable to move, we played

possum, staying silent with all lights extinguished, trying not to draw

attention to ourselves. As dawn broke, the wind was still

strong and the German gun battery on the shore started shelling us again,

but a passing destroyer returned fire and the shelling stopped. Further out to sea, the battleship,

HMS Nelson, started firing her 16inch guns. The sight

and sound of the shells passing overhead was an awesome sight.

We

were still receiving occasional enemy fire so we raised our anchor and turned into the wind

to remove ourselves beyond the range of the enemy's guns, and to hopefully

return to England for repairs. This proved

ineffective, but another landing craft, lying at anchor because her

engines were inoperative, presented a God given opportunity to save both

craft. Was it possible that the two craft, tied together, could function

sufficiently well to return to England using our engine and their rudders? We

were still receiving occasional enemy fire so we raised our anchor and turned into the wind

to remove ourselves beyond the range of the enemy's guns, and to hopefully

return to England for repairs. This proved

ineffective, but another landing craft, lying at anchor because her

engines were inoperative, presented a God given opportunity to save both

craft. Was it possible that the two craft, tied together, could function

sufficiently well to return to England using our engine and their rudders?

[Photo;

Lt Cdr H L Hurley in 1969].

It worked, and, as we moved further

out to sea, a destroyer pulled close by to check on our condition. By now

we were making slow but steady progress and reassured them that we would manage,

leaving them to more important tasks. It took the rest of that day and

night before we reached Portsmouth the following morning. After repairs

were carried out, we rejoined the remains of our flotilla in Portland and

began ferrying American trucks and

troops from Portland to the US beaches for the rest of the

D-day campaign.

Footnote by Lt Cdr Hurley's son, Chris: My father can be seen on the stamp in silhouette standing on the bridge of LCT 858.

His description in this text of “going over the side” to try to rescue

soldiers in the sea is him deliberately underplaying what actually

happened as this was all done under heavy enemy fire, just off Gold Beach

when the soldiers in the water were being targetted.

Acknowledgements

This account of LCT858 was written by

Lt Cdr H L Hurley in November 1998. It was

redrafted for website presentation by Geoff Slee and approved by his son,

Chris, before publication. We are indebted to Chris for permission to

publish his father's story and the accompanying photos.

|

The SP guns

also had a less orthodox role as they

approached the landing beaches on their LCTs... they would fire

on beach targets from their craft's tank deck. This was our hazardous task

as part of the initial assault phase on D Day, when the full might of the

enemy's defences were largely intact. We approached our designated

training landing

beach ahead of the initial assault troops to “soften up” the imaginary

German defences. As the guns fired, they created a “creeping barrage” that

moved up the beach as our LCT moved forwards.

The SP guns

also had a less orthodox role as they

approached the landing beaches on their LCTs... they would fire

on beach targets from their craft's tank deck. This was our hazardous task

as part of the initial assault phase on D Day, when the full might of the

enemy's defences were largely intact. We approached our designated

training landing

beach ahead of the initial assault troops to “soften up” the imaginary

German defences. As the guns fired, they created a “creeping barrage” that

moved up the beach as our LCT moved forwards.

Whilst all this was going on, the First

Lieutenant went over the side in a life vest into the sea to try to rescue

soldiers seen floating in the water. Unfortunately, each time, the soldier

was found to be dead and the bodies were quickly swept away by the sea.

Whilst all this was going on, the First

Lieutenant went over the side in a life vest into the sea to try to rescue

soldiers seen floating in the water. Unfortunately, each time, the soldier

was found to be dead and the bodies were quickly swept away by the sea.