Landing Craft Tank

1171 - LCT 1171.

My World War - A thoughtful account of one young Royal Navy recruit to

the mayhem of war.

Background

His Majesty's Landing Craft Tank, HMLCT 1171. In August 1942, at the tender age of 18, Austin Prosser

joined the RN as an ordinary seaman at H.M.S. Raleigh. He was

commissioned a midshipman in December 1942. Apart from a short time

patrolling on

the Torpoint ferry he spent the next four years in Combined Operations.

His pay office was

H.M.S. Copra and also

H.M.S. Quebec

at Inveraray. After drawing cash from pay offices in various parts of the world

without any problems, at the final reckoning he owed H.M.S Copra £70...

by today's standards that was well over £1,000. He joined the navy broke, lost

all he possessed on three separate occasions, and left the navy worse than

broke... but it had been an amazing and rewarding experience. All photos

courtesy of Austin Prosser.

After five years at grammar school the headmaster

announced that, in view of the war economy, it was a waste of time and money

my taking the school certificate and it was suggested that I leave. His

final report to my parents proclaimed, 'This boy is academically

undistinguished, has a lot of latent energy and has three good subjects -

rugby, tennis and swimming.' This report obviously helped me in my new

career at the Admiralty where I was employed for two years as a grade

3 temporary clerk.

I joined the Home Guard which was very much as depicted

in the 'Dad's Army' TV series. I achieved the exalted rank of lance

corporal. For those not familiar with this comedy series, it depicts a small

local Home Guard unit under the command of an inept, bungling and rather

pompous bank manager. The unit is ill equipped in terms of arms, equipment,

training and leadership, and not surprisingly finds itself in all manner of

problems and self inflicted embarrassing situations.

During these two years I tried to join the Navy but was

turned down because of my age. However, with the benefit of a grammar school

education, I was offered the opportunity to enter as a `V scheme rating.' I

never really understood what it was but I managed to fail the entrance exam

in maths and probably in all other subjects as well! I also joined the Bath

Saracens Rugby Club and I well remember my first game against the

Welsh Guards then stationed outside of Bath. Despite my 6 foot, 14 stone

physique, I was hammered into the ground!

Joining Up

The great day came on 12/8/42 when, aged 18, I

joined the Navy. I reported to H.M.S. Raleigh at Torpoint in Cornwall

and joined 10 mess, Forecastle Division. There were about 20

of us in the charge of Chief Petty Officer Bungy Williams. He had been

recalled at the beginning of the war after a long retirement and seemed very

elderly to us youngsters.

Having settled in I immediately wanted to go home to

Mother, but they wouldn't let me! A fair percentage of

the mess were 'ex-borstal' but they were a good bunch of lads from whom I learnt

about coping with the rigours of life. My first setback came when the Navy

had no uniform to fit me so they kitted me out with overalls making me

instantly suitable for unskilled manual work. My first job was to flush out the `heads'

(loos) by lifting up manhole covers and flushing them out with a high

pressure fire

hose. Looking back the outcome was predicable but when my assistant turned on the fire hose full blast I

was plastered from head to foot in the proverbial! I decided there and then

that I didn't like the Navy but thought the authorities should have the

opportunity of turning me into a sailor.

Early Experiences

The camp cinema projector

broke down and each division

was ordered to put on a concert party. Volunteers were invited to come

forward and I committed the heinous sin of

responding. However, it resulted in an interesting if not lucrative sideline

since I joined a concert party travelling around the various camps to

entertain the occupants. The shows

were reasonably well attended as we were playing to a captive audience!

One of my jobs was to play the piano which, although I say it myself, I did

quite well. As a result of this experience H.M.S. Raleigh ordered me to run the Forecastle

Division's efforts and to act as compare. We were judged the best and won a

prize of an extra day’s shore leave. The prize was very welcome but, with an

income of half a crown (12.5p) per day, we had no money to spend!

Life went on unrelentingly and I spent some time

running around the parade ground carrying a shell above my

head. (For the uninformed this was a common form

of punishment). This extra exercise kept me fit and when Forecastle Division

started

rugby training I immediately volunteered... again. On one occasion I

refereed a match between Keyham College, a training depot for naval

engineers, and the Army. It was my very first attempt at refereeing a game

and, when the game was over, I was booed off the field. The outcome of all this was

that at the tender age of 18 I was selected to play for H.M.S. Raleigh out of over 4,000

sailors. This was quite an honour but sadly it carried no privileges but, if

I was injured, I might be invalided out and go home to mother!

I finished up playing second row forward with the

Training Commander who was an awesome high-ranking figure. However, out of

uniform and wearing his rugby kit he was just another human!

A Commission!

In October 1942 he informed me

that I was being put forward for a commission. Somewhat taken aback, I said

'but I failed all my entrance exams.' He explained that a new type of Commissioned Officer

was required oriented towards Combined Operations

and the Commandos. I didn't understand why, with my poor educational

qualifications and limited sea experience, I was thought suitable for a

commission. It transpired that the Navy needed large numbers of officers very quickly for a

specific purpose and, after a week’s leave at home and an eighteen-hour

train journey from Plymouth to H.M.S. Lochailort, forty miles north of Fort William,

I found myself in an entirely different world. I was to spend six weeks of hell

up there trying to become, concurrently, both a commando and a gentleman.

The latter was the difficult part!

Officer Training

The officer training was one of the most traumatic, but

beneficial, of my naval career... indeed of my whole life. It improved

my attitude and outlook for the better. The course was of necessity very

tough bordering on the sadistic... of thirty-six candidates who started only sixteen passed.

My fitness,

physique and sheer stubbornness helped me through the physical challenges. On

the 23/12/42 I walked into

Moss Bros. in London as a matelot and came out as a

Midshipman R.N.V.R. I was proud of my achievement and

subconsciously realised that I wasn't a complete moron after all. However, I always

knew that appointments like mine where to meet a particular contingency of

war and that as such we were expendable... we were a kind of commissioned cannon fodder.

The officer training was one of the most traumatic, but

beneficial, of my naval career... indeed of my whole life. It improved

my attitude and outlook for the better. The course was of necessity very

tough bordering on the sadistic... of thirty-six candidates who started only sixteen passed.

My fitness,

physique and sheer stubbornness helped me through the physical challenges. On

the 23/12/42 I walked into

Moss Bros. in London as a matelot and came out as a

Midshipman R.N.V.R. I was proud of my achievement and

subconsciously realised that I wasn't a complete moron after all. However, I always

knew that appointments like mine where to meet a particular contingency of

war and that as such we were expendable... we were a kind of commissioned cannon fodder.

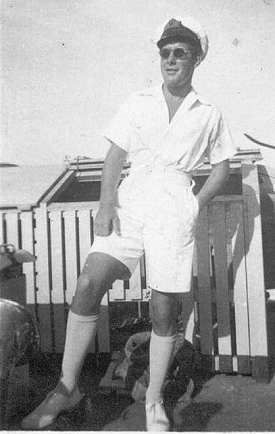

[Photo; Austin in tropical kit].

I strutted my newly acquired stuff in Bath during my Xmas

leave and was happy to assure my family and friends that they were now safe

in my hands! I met a teacher from my old school who, in some disbelief, looked me up and

down and said `Prosser, we must be short of manpower.' However, I was

admitted to that holiest of inner sanctums, the master's common room, where I listened to an

impressive list of felonies I had committed over the five years I was at the school.

With some relish I was informed that I had broken the school record for Saturday morning

detentions. It was all good natured banter and I was congratulated on my

achievements and taken to meet the headmaster

who assured me that he always thought I would go a

long way... but he failed to say in which direction!

HMS Helder, a Butlin’s

holiday camp at Brightlingsea in Essex, was my next port of call. It had been

requisitioned by the Navy and we did our best to turn it back to its

original use but without success. We were called 'Officers under Training'

and had to wear reefer jackets, a white silk scarf in place of a collar and

tie, grey flannels, black boots and long brown army gaiters. We were marched

around, in fact, doubled around, by a petty officer who had a

disparaging way of saying `Sir'. It was an uncomfortable period since

we did not fit into the culture, traditions and habits of the officer class. We

stood out like sore thumbs and had to take a lot of stick.

At HMS Helder we underwent further toughening up

training and instruction on the handling of various types of assault craft

and some military vehicles. Not surprisingly while we honed our skills we

found ourselves involved in many collisions at sea, groundings and getting

stuck on the mud. It was during this period that a profound

interest in

boats emerged... an interest that has stayed with me all my life. The urge to go home

to mother dropped off but she was always there when I was broke; a frequent

occurrence as my pay as a Midshipman was ten pounds a month.

The Admiralty were not renowned for their generous

leave or recovery periods and on completion of the course I was sent to Bracklesham

Bay in Sussex for more training, this time to practise beach landings on

Hayling Island. I recall a scare that the Germans had landed a party in the

area from a submarine. The duty officer sent me out with a patrol ...

fortunately for the Germans and me it was a false alarm.

North

Africa

In March 1943 at the age of eighteen and a half I joined

an assault flotilla from HMS Roseneath on the Clyde. My assessment

was that I was lacking in both training and experience for active service

but the authorities wouldn't listen. Contention and conflict with my seniors

was by now a normal part of my life and continued to be the case in the months and years ahead.

The base Commander appointed me Officer of the Guard

which carried a number of welcome perks with it not the least of which was a Buick car as my

personal transport. The Roseneath base had been loaned to the Americans and

on its transfer back to the RN they left their transport behind. The job

required me to visit the nearby town of Helensburgh to supervise shore

patrols which often allowed me to excuse myself from mess dinners with all

their pomp and ceremony. In addition I

earned the odd pint in local pubs by transporting my fellow junior officers on shore leave.

Sadly these good times came to a sudden halt when I turned a Jeep over

carrying 18 junior officers after a very late night party in the junior

officers’ wardroom. I was brought up before the Commander next morning and

threatened with all kinds of nasties including my first threat of a

court martial.

Before we left Roseneath Admiral Vian and Admiral Lord

Louis Mountbatten, who was the Chief of the Combined Operations Command, inspected

us. As was normal for the times we had no idea where we were going. The only

clue was our purchase of tropical white gear and the issue of khaki shorts,

shirts, hose tops, boots and khaki cap tops in lieu of our white ones... plus

webbing equipment and a Smith and Wesson revolver. I didn't think much of

these developments but, I needn't have bothered, since a few days later I was in Newport, South Wales to join a Dutch liberty ship.

The liberty ship had been refitted

to become a 'Landing Ship Infantry' by turning her holds into barracks to

carry troops and altering her upper decks to carry assault craft. The set-up

was not very

comfortable but better than nothing as I was to learn over the next few

months. I had no ambitions to be a soldier but I found myself undergoing

extensive small arms and demolition training, on completion of which I returned

to the Dutch merchant ship Franz Van Meiris, also known as the Empire Eisult (I think). We were still in the

dark as to our destination and the reason for our small arms training.

We were integrated with the ship’s company and for the

first time I began to feel like a real sailor. The crew gave me every

encouragement and help to make good my shortcomings for which I was

eternally grateful. After working up we moved to Liverpool, then into the

Clyde, where we joined up with a task force. We then embarked Canadian

troops and prepared to sail with our destination confirmed as the

Mediterranean. Our convoy travelling at 7 knots headed due west into the

Atlantic then south and finally east into the

Mediterranean - the direct route via the Bay of Biscay was not an option

because of enemy submarine activity. Despite the circuitous route we were attacked on a number of occasions, losing

some ships.

After what was a hectic passage we arrived off Cape Passero

in Sicily in September 1943 where we were due to disembark our cargo of men,

materials and vehicles. The troops we carried were amongst the first

invasion size force to land in Europe since the

evacuation at Dunkirk in the early summer of 1940.

Having completed the landing we stayed on the beach for two weeks carrying

out recovery work. An interesting interlude arose when I picked up Lord Louis

Mountbatten, two Italian Admirals and an Italian General. I took them out

to a destroyer but sadly I didn't get any autographs. The press filmed the

event and although I never saw the film it will no doubt still be lying

around in a forgotten archive somewhere.

Most of us caught dysentery and others dengue

fever. We were shipped back to Bizerta in Tunisia by which time some of us

were seriously

ill. After my recovery I was despatched to a tented camp in Djijeli, a small

town on the coast. This was no holiday camp with cemeteries on two sides, an

Arab slaughterhouse on a third and the sea on the fourth side. All the waste

from these various institutions discharged onto the beach including the odd

animal carcass Swimming or bathing were the preserve of the brave and

the stupid.

My next appointment was the

watch-keeping officer on Landing Craft Flack (L.C.F) 9 moored at Bougie.

It was in essence a landing craft tank (LCT) fitted out with numerous anti-aircraft guns, which were manned by a detachment of Royal Marines. After

the accommodation I had experienced over the previous months, living aboard

this ship was bliss. I was still a midshipman as I couldn't become a

sub-lieutenant until I was nineteen and a half in February 1944.

I well remember being duty officer on board, all the

others being ashore. I was feeling very nostalgic listening to Vera Lynn singing about Dover and other

evocative places. Once more I wanted to go home to mother but my dreams were

shattered when a Royal Marine knocked on the wardroom door, the upshot of

which was my transfer to major landing craft. We steamed up and down the

Mediterranean to keep the Germans on their toes until we were recalled to

the U.K. This was a bit of a surprise since the speculation was that we were

bound for the Greek theatre of war. At Gibraltar I transferred to an

infantry landing craft bound for the U.K. T with a complement of three officers,

including myself, plus crew. The ship had seen a lot of active service

including the Salerno and Anzio landings and was in dire need of a refit.

The officers we replaced were suffering from DTs and were taken off the ship

in Gibraltar for medical attention.

We left in convoy heading for Milford Haven but, much as

expected, we broke down and lagged behind the convoy. From the relative

safety of our position about twenty miles east of the convoy we watched it

being attacked by German submarines and surface craft. Later a frigate checked

our position and advised us to steam independently for Milford Haven. We arrived

there safely after what seemed to be an eternity with a pint or two of

English beer high on the our priority list! By various routes we travelled to Grimsby where we

'paid off' and went on two

weeks leave.

Landing Craft Training

It was nice to see family and friends although most of my

school friends were away in the services. However, I was pleased to receive

orders to report to the Marine Hotel in Troon, Scotland, famous for its

international golfing centre. We were made honorary members of the golf club

and used the bunkers for anything but golf. I was once again an Officer

under Training but this time involved in the handling of

major landing craft and learning astral and terrestrial navigation. I was already reasonably proficient

at the latter having done a

fair mileage at sea on major landing craft as a watch-keeping officer.

We were very much a mixed bunch of trainees - some like me had just returned

from the Mediterranean theatre of war and the rest had just completed an

officers’ training course. The difference between the two groups was obvious

from a distance because their uniforms were immaculate while ours were

showing the signs of wear and tear.

After our first parade the Training Commander in charge

insisted that all officers should have a grommet in their cap. A grommet is a circular piece of wire that keeps the crown of the cap in shape and uptight.

It was an unofficial status symbol to remove the grommets from our caps and let them

flop down. R.A.F pilots

and the submariners had a similar symbol by leaving the top buttons of their pockets undone.

We did not therefore greet this order with enthusiasm but we had no choice

but to comply. There were no naval outfitters nearby so grommets quickly

acquired the status of a 'must have' item. As the situation became

increasingly desperate, all newly commissioned officers had to guard their caps with

their lives but the Commander obviously thought his cap was inviolate. He

left it unguarded on

the hallstand in the Officers so I whipped the grommet out of his cap and slunk

away. Next morning on parade I appeared with the others looking very smug in

my regulation cap. The commander was at the head of the parade with a

rather collapsed cap. There was an enquiry with a threat to cancel all shore

leave if the culprit didn't own up. I was once more hauled up before the

Commander and threatened with lots of horrible things but eventually I was

congratulated on my initiative!

After completing the course and some leave I proceeded to Glasgow as First Lieutenant to HM Landing

Craft Tank 1171. On arrival at Bowling shipyard just outside of Glasgow I

asked the dockyard police where H.M.L.C.T.1171 was. He pointed to a large pile of

metal on the jetty and said, 'there it is'. After the bits and pieces were assembled we became a ship

and eventually a ship's company under the command of Sub Lt Ronnie

Parks. We set off from Glasgow to carry out our 'training up' programme on the

west coast of

Scotland. On the first night we anchored in Lamlash Bay off the Isle of

Arran alongside the WWI monitor H.M.S. Erebus with her massive 16

inch guns. She was a colossus alongside our ship which was a mere 230 feet

in length. With the differences between the two vessels fresh in our minds we may have thought of our ship in less flattering

terms... such as a flat-bottomed b@!#*$d!

Training, as much as we were able to do in the time, went

ahead fairly well. Fortunately most of our crew had been on landing craft

before so were all fairly experienced. We finished up at Oban, further

north on the west coast of Scotland, but not knowing where we were going or

what we would be doing. Here we carried out more training and prepared the

ship for whatever the planners had in store for us. We were always on the

lookout for clues and rumours were whizzing around by now... from the amount

of hardware in the area it was certain something big was about to happen.

Normandy

We received orders to sail

for Plymouth and the night before we left Oban we had a pretty hectic party

in the Officers’ club with a load of RAF types. The following morning I

presented myself before the base commander under threat of a court martial

for 'un-officer' conduct but, once again, he let me off! I suspect he knew what future plans the Navy had for me and

he considered that would be punishment

enough!

We had an extremely rough trip to Plymouth during which

we discovered what a battering our ship could take. Some ships had faired less well and others had been lost. In Plymouth we learnt

that we were to be attached to the American forces. A near mutiny was

threatened when American senior officers visited our ship to explain the

implications of our attachment to their Navy. There must have been many

important operational matters discussed but amongst it all was a ban on

alcohol to bring us into line with the US Navy 'dry ships' policy. This

immediately captured our attention and there was uproar! After a lot of

discussion, and a few diplomatic moves to keep the peace among the Allies, it

was decided that nothing should change. In the event it was a popular

outcome for everyone since the Americans spent a fair amount onboard helping

us deplete our stocks of drinks in case, as was expected, we would be on a

one-way mission!

More training and routine maintenance on board followed

and we had some large folding extensions

fitted to our bow door to make it easier to unload vehicles on the beaches. Then the time came for our flotilla, the 57th (otherwise

known as the 57 'Heinz') to take on board our cargo at St Johns on the

south (Cornish) side of the Tamar River. We loaded six Sherman tanks, six

half-track ammunition lorries, two half-track ambulances and all their

crews. Our ship was now rather overcrowded.

At this late stage we finally found out where we were

going and what was expected of us - we had to deliver our precious cargo

onto a beach codenamed Omaha in Normandy... a name that meant nothing

at the time but has since been etched into the collective memory of

subsequent generations. We received visits from the base staff to wish us

'bon voyage' (I expect with tongue in cheek!) and the ship was sealed. For

security reasons we

were not allowed any further communication with shore.

We eventually sailed in convoy for France. We hit some

foul weather and the soldiers didn't look at all interested in the War.

Because of the bad weather the landings were postponed, the convoy returned to Cawsands Bay in Plymouth Sound

where we anchored to await further

instructions. Gunboats surrounded us to stop any communications with the

shore and it was here that the first tragedy of the invasion occurred.

Because we thought ourselves to be on a 'one-way' ship we had consumed all

the alcoholic drinks on board the night before we sailed and there was

nothing left!! This bad situation was soon remedied with the retrieval of a

jar of neat alcohol from an American ambulance conveniently parked in our

hold. The Americans topped it up with pure fruit juice and called it

"invasion broth"; it tasted absolutely revolting but it certainly helped

them out of their depression.

The next day we set off on

our interrupted journey in much improved weather with other ships from Dartmouth and Torbay.

Off

Portland Bill the convoy hove to to let the American Battle

fleet pass. It was an amazing and impressive spectacle to see so many great ships

together. We arrived at St

Catherine's lighthouse on the south side of the Isle of Wight where there was a

marker buoy showing the entrance to the 'swept channel' to the beaches (a channel swept of mines).

It was dark and there were no steaming lights so the threat of collision was

ever present. All the while many hundreds of aircraft

were flying overhead and although my contribution was small I felt a strong

sense of responsibility to do my duty. By the time we arrived at Omaha Beach we were acclimatised to

all the noise and activity. It must have been a daunting prospect for those

who had not seen action before.

We arrived off Omaha beach on time at D+2 0800 hrs. It was absolute chaos!! The events on Omaha

Beach on D Day were as bad as widely recorded, although little has been said

about the involvement of the British in the initial assault. Our flotilla of Landing Craft Tanks unloaded its cargo and was ordered to lay off the

beach and stand by for possible evacuation as the Allied forces were meeting

very stiff opposition.

The flotilla was carrying anti-aircraft barrage balloons so we formed a

cordon of

balloon protection around the ships. The following day we sailed back to Portland

to uplift our next cargo.... a journey that cost us three ships lost to

enemy action.

We loaded more American tanks and

their crews and headed back to Omaha Beach. In all we completed 18

trips every one of which was different from the others and worthy of

recording. One such saw us heading back to Portland in a westerly gale and

in company with other ships. A few miles off the Dorset coast the wind and

tide were against us and the sea was increasingly menacing. We were

travelling light and the flat bottomed landing craft, which in the best of

conditions was difficult to control, bounced about making ship handling even

more of a problem. We hit a big wave which caused the bows of the ship to crash

down and the shock sheared off the clips holding up our bow doors. The

doors, which weighed ten tons, folded down right under the ship but,

fortunately the watertight doors inside the tank deck held and kept us

afloat. However, the extra drag reduced our

speed from ten knots to about two knots with both main engines going flat

out. It took us eighteen hours to

reach Portland dockyard eighteen miles away. The other ships had gone on

ahead as they were desperately needed to get more tanks back to France. When

we eventually arrived in harbour we went alongside a dockyard crane. A diver hooked

a cable on to the door, the crane raised the

door to its normal position and the offending clips were repaired. We loaded with tanks and

were off again with hardly any rest.

In October we had delivered a load of supply wagons to

the Omaha beach. We were travelling independently by then and we left the

beach about 1600hrs and headed north towards the Isle of Wight. Although the

weather at the time was fair we had no idea of what was in store and by the

time we got off St Catherine’s light we found ourselves in a force ten gale.

It was Friday October 13th 1944 and once again the ship was travelling light

and we were being thrown all over the place. It was one of the worst seas I

had experienced.

We were alone and heading towards Portland at reduced

speed. The bows reared up, crashed down on a very steep wave and with a

mighty crash the ship broke her back The situation we found ourselves in was

pretty desperate since we had no means to call for help and no power from our main engines.

The crew was marvellous and stayed very calm as we all strove to keep the ship afloat.

Our position was dire. It was pitch black in torrential rain and with the wind getting stronger

by the minute. The situation deteriorated further when the two still

connected parts of the ship ground against each other. Showers of sparks

flew from the hull lightening the sky like a firework display. The flashes were seen by another L.C.T and a frigate.

They came back to assist but because of the high seas could not get near.

The ship broke in half at midnight and, as the bow

section of 100 feet floated away it was sunk by gunfire because it was a

hazard to other shipping. We were left on the stern which was taking a

battering from the seas and by then we had no light as the generators had packed

up. Eventually the commander of the other L.C.T. in our

flotilla (regretfully I forget its number), managed to manoeuvre his ship

alongside and despite the tremendous waves managed to take off all the crew

except the Skipper Ronnie Parks and myself. We stayed aboard to carry out

the abandon ship routine.

The assisting L.C.T. was commanded by Lieutenant Nash who

was a professional fishing skipper from Grimsby. The tremendous seamanship

skills of skipper Nash certainly saved all our lives and his skills didn't

stop there. After a struggle we secured a tow and proceeded stern

first towards Southampton. Unfortunately the tow parted and, as we were not

able to rig up another one, we sank at 0200 hours. Ronnie Parks and I

went over the side, in my case clutching a jar of navy rum (more inside me

than out). Skipper Nash picked us out of the water and took us home. It was

farewell to a good ship that had carried out the job for which she was designed and under very rigorous conditions. She lies

at rest

on the bottom about 18 miles SW of the Isle of Wight.

Survivor's Leave

I travelled to Portland by sea to make

arrangements for survivor’s leave. For the third time in my short adult life I

found myself with no kit or possessions. I had lost everything when we were

bombed out of our Bath home during the blitz in 1942, again during the

Sicily landings and finally when LCT 1171 went down. As I had no home, everything

I owned was with me. All I had was my seagoing kit which comprised a blue battledress and not much else.

At Portland I booked into the officers’ mess and enjoyed

the luxury of a hot bath, clean underclothes and shirt but no uniform -

there were none!. Next day I travelled first class with some W.R.N.S. officers and a Canadian officer who was wearing a kilt.

It was impossible not to notice that this Canadian followed the tradition of

wearing nothing under his kilt! There were some comments about my

scruffy appearance, but after I poured out a rather plaintive story of my

recent activities, there was a fair bit of backslapping and the sharing

of hip flasks.

When I arrived home I was told that my cousin Dennis, an

officer in the Paras, had been hit by a bullet through his neck on the same

day that I lost my ship. The poor old chap was in an awful mess, at death’s

door in hospital in Birmingham but lucky to be alive. To this day he has a scar

on each side of his head.

I was now home on indefinite leave to get myself

reorganised in readiness for my next posting whatever that might be. This

involved kitting myself out in new uniforms and clothing generally. The

'Officer Uniform Replacement Depot' was a great help. They

kitted me out with second hand uniforms mainly donated by the families of

dead naval officers. The only ones that would fit me belonged to a rear

admiral. The gold rings were removed from the sleeves and the rows of medal

ribbons from the chest to be replaced by my one ring and

three medals. However, the old marks showed up well and I walked around like a

demoted admiral!!

After a few weeks leave I wanted to get back to sea and sent the Admiralty in London

a telegram requesting appointment instructions. I had a very quick but terse reply telling me to report to Admiralty London with kit

which I did with slight trepidation. On arrival in Admiralty the Combined Operations appointment officer promptly

informed me that I was in serious trouble and had to report to the duty

officer immediately. He turned out to be a four-ringed captain who

remonstrated with me. Apparently it was unprecedented in the

history of the Admiralty for a naval reserve sub-lieutenant to send a

telegram to Admiralty requesting appointment instructions. After a lengthy

berating I was dismissed but, as I was about to leave the room, he called

me back and congratulated me for my enthusiasm and initiative.

HM LCH 75

HMS Westcliff,

a Combined Operations holding base at Southend,

was my next port of call. After several idle

but pleasant weeks my orders were to report to Chatham to take over U.S.LCI 75

(Landing Craft Infantry) from the Americans whilst she was converted to an RN headquarters ship, H.M.LCH 75. Thus started the next part of

my involvement in the War and all because of my telegram to the Admiralty.

HMS Westcliff,

a Combined Operations holding base at Southend,

was my next port of call. After several idle

but pleasant weeks my orders were to report to Chatham to take over U.S.LCI 75

(Landing Craft Infantry) from the Americans whilst she was converted to an RN headquarters ship, H.M.LCH 75. Thus started the next part of

my involvement in the War and all because of my telegram to the Admiralty.

The conversion took a couple of months during which time I was billeted in

Chatham Barracks. It was not exactly the ideal place for an active

young naval officer whose regard for naval tradition and etiquette fell

somewhat below the expectations of higher authority. Many incidents and misdemeanours of a social

nature occurred which caused the eyebrows of many a senior officer to elevate

skywards. In this regard I may have been regarded as somewhat of a loose

cannon!

A new crew

was appointed under a senior Lieutenant as Captain and a

senior Sub Lieutenant as First Lieutenant. I had become rather fond of

the ship and asked to stay on as ship's company. I was appointed Gunnery Officer and Watch Keeping Officer...

they obviously didn't know what I knew about my gunnery skills!

Familiarisation and sea trials off Sheerness passed very

smoothly because most of the crew of 36 had a fair amount of sea

time to their credit. We expected

to spend the next year or so together so a good start was important. It was

during this time that we learnt that we would be going out to the Far East.

As this was going to be our home for the next eighteen months, with a many

thousands of sea miles ahead, we were fortunate that the ship was reasonably

comfortable.

After a spell at sea 'working up' we were ordered to

join a convoy at Southend bound for Plymouth. During sea trials we had

discovered that H.M.L.C.H.75 was a pretty lively ship in heavy weather. This

didn't worry me unduly as heavy weather seemed to be my constant companion.

True to form we hit a force ten

gale going through the English Channel which really tested the ship.

However, she came through with flying colours. We arrived off Plymouth at night

in filthy weather and followed an American Landing ship into the harbour. It ran onto the breakwater and started to break up. She was at least

2000 tons and we were simply not big enough to do anything to help. We

radioed for help and a tug came out to sort out the situation. The rest of

our time in Plymouth was spent in preparations for the long journey to Japan.

(Photo; Ship's company).

After a spell at sea 'working up' we were ordered to

join a convoy at Southend bound for Plymouth. During sea trials we had

discovered that H.M.L.C.H.75 was a pretty lively ship in heavy weather. This

didn't worry me unduly as heavy weather seemed to be my constant companion.

True to form we hit a force ten

gale going through the English Channel which really tested the ship.

However, she came through with flying colours. We arrived off Plymouth at night

in filthy weather and followed an American Landing ship into the harbour. It ran onto the breakwater and started to break up. She was at least

2000 tons and we were simply not big enough to do anything to help. We

radioed for help and a tug came out to sort out the situation. The rest of

our time in Plymouth was spent in preparations for the long journey to Japan.

(Photo; Ship's company).

We moved onto Falmouth to meet up with 28 Landing

Craft Tank which we were to lead to Cochin in India. There was a lot of activity

'storing' the ship and generally getting ready including a trip up to Liverpool to meet our escorts and

to discuss convoy tactics. We embarked the convoy senior officer in

Liverpool, returned to Falmouth and prepared for sea. After a few last

minute rushes and a number of very tearful farewells to W.R.N.S. boat crews,

we set off on our next adventure courtesy of HM Government.

Journey

to the Far East

We formed the convoy in Falmouth Bay and headed south on

the direct route to Gibraltar via the Bay of Biscay as it was now considered to

be free of enemy submarines. Sadly the Bay was in one of its more contentious

moods and at least 14 of the ships received severe damage that rendered them unfit

for further progress and the whole convoy

was ordered back to Falmouth for repairs. It was a painfully slow trip so

the approaches to Falmouth were a very welcome sight.

After about two weeks we once again set sail for

Gibraltar at a steady convoy speed of seven knots, the maximum speed of

seven motor fishing vessels that had joined the convoy. After a fairly

uneventful couple of weeks we arrived in Gibraltar, reasonably unscathed,

where the crews were given a much-needed two week break. The landing craft

were designed to be lived on for a few days at time not three weeks or more

so normal comforts were impossible to provide. As a result we all received

an extra hard living allowance in our pay and we certainly deserved it.

The next port of call on the journey eastward was Malta

followed by Port Said in Egypt. Along the way there were many incidents and

accidents one of which concerned a seaman who fell down a hatchway and

broke a load of ribs. On medical advice the seaman was taken to Tobruk

for treatment which resulted in us leaving the convoy to sail off alone. On

our eventual arrival in Port Said we discovered that our convoy had sailed on to

H.M.S. Saunders, the landing craft base on the Bitter lakes on the

Suez Canal. All things considered the top brass decided to dry dock our

vessel to have her 'bottom

scraped' before we sailed on to India. This was in the first week in August 1945

and my two fellow officers took advantage of the lull in activity to take a spot of leave.

It fell to me to organise everything and on August 3rd,

my 21st Birthday, I was kept busy moving the ship around. That

night we had a splendid party on board when much liquor was consumed.

End of WW2

The Atomic bomb was dropped on Japan

on August 12th 1945 and our war came to an abrupt halt. In an instant

we had become superfluous. In the event we spent two months in

Port Said awaiting further instructions. The time was filled in with leave

and a trip to Ismaillia. After being confined on a small

ship for a fair amount of time this interlude was absolute bliss. However, there was a need to

keep the crew occupied and to maintain the crew's operational effectiveness.

This was achieved with short trips to places like Alexandria where the crew

easily integrated into the local social life.

Long Way Home

As the picture in the far east became clearer we received

orders to proceed to the Pacific Islands to assist with relief work. We were

then routed through the Suez canal and the Red Sea arriving in Aden just

before Christmas 1945 where we were once more dry docked for another

scraping of the hull to remove barnacles. A good number of social

events later and we were on our way across the Indian Ocean to Cochin,

our original port of destination. However a signal from Admiralty London was

received ordering us to return to Norfolk Naval Base in the USA to 'Pay

Off'... in plain language to give the ship back to the Americans.

After the receipt of the signal from the Admiralty there

was terrific excitement. Many of the crew were due for demobilisation and

could see civvy life in the offing. We about-turned and set off for Aden but our engines,

which were getting a bit tired by now, started playing up. We stopped off at

the island

of Socotra on the north east point of Africa to effect repairs.

This we did and in a few days we were heading off again

towards Aden to rest the crew and then up the Red Sea and Suez Canal to

Kabret. Our skipper was due

for demob, so we embarked a new skipper, had a rest and then sailed on to

Port Said where we remained for a month. While we waited for replacement

crew to arrive from the UK we socialised with many old friends. It was in

Aden that I sent the 'ship's' 1945 Christmas card to my parents back home.

This we did and in a few days we were heading off again

towards Aden to rest the crew and then up the Red Sea and Suez Canal to

Kabret. Our skipper was due

for demob, so we embarked a new skipper, had a rest and then sailed on to

Port Said where we remained for a month. While we waited for replacement

crew to arrive from the UK we socialised with many old friends. It was in

Aden that I sent the 'ship's' 1945 Christmas card to my parents back home.

By this time the ship had been my house and home for

about 15 months. At Alexandria we were due to pick up civilian personnel to take on to Malta.

However, the Arabs were in revolt and the

civilians were not ready to leave. We offered our services to help quell the

revolt but were told that we were not required. There was a similar response

when we tried to get involved in some lucrative post-war rackets

which involved carrying stores back to Greece and selling them off cheap.

When we sailed to Malta we were due to spend a

few months decommissioning the ship. Sub. Lieutenant Osborne and I were

both due for demob. He decided to go and I decided to stay with the ship

until we arrived in America. I took on the duties as First Lieutenant and we

acquired a young inexperienced officer to take on my old duties. We removed all the English equipment,

undertook more training where it was required and generally prepared the

ship for handover. There were many sad farewells to the local ladies and I expect

many unfulfilled promises to follow. We sailed for Gibraltar where we

awaited the arrival of ex-lease-lend landing craft also bound for Norfolk

Naval Yard in Virginia.

It was a number of weeks before we were able to form a

convoy and this could have been a frustrating and boring time had it not

been for Army and Air Force personnel

ashore and a few liaisons with the Queen Ann’s Royal Nursing Sisters, a body

of young ladies more than worthy of our attentions! In fact our farewell

party was held in their mess and I remember well that a

goodly supply of ’Vat 69‘ whisky was consumed.

We were routed to Ponta

Delgada on the island of St Miguel in the Azores. We arrived there without

mishap and in fairly good weather, but our main engines were 'tired' and in

need of attention before we could cross the Atlantic en route to our next

port of all... Bermuda. The rest of the fleet sailed on and we waited for

the delivery of the eight new diesel engines we needed. Whether or not we

had the experience amongst the crew to undertake the task was another

matter. In temperatures of around 100f the last of our generators failed and

without air-conditioning life on board became intolerable. The British

Consul fixed us up with hotel accommodation which was sheer bliss!

We were well entertained by the Portuguese inhabitants,

visiting all the places of interest ashore and a few other foreign ships

which arrived in port. However, it all came to end when H.M.S. Porlock Bay was instructed to tow us as a hulk to Bermuda, a very long and

arduous tow. We were very sad about the ignominious way

H.M.L.C.H.75 would finish her distinguished career. We managed to

rendezvous with the Porlock Bay under our own power and to rig up a

tow with the help of experienced professional sailors from her crew. We then

battened down the ship so that she was completely watertight and secured all

loose equipment on the decks. When the first lieutenant of the Porlock

Bay and myself were satisfied that all was ready we transferred by boat

to his ship. Our poor old girl looked forlorn and abandoned "hanging" on

what looked like a length of string. For me it was a

sad and pathetic sight!

We were integrated into Porlock Bay's watches and

every day I came up on deck I looked astern to see the ‘Dear Old

Lady’, following relentlessly astern, incapable of doing anything for

herself. Little did we know the fate that awaited her, back at her place of

birth. On arrival off Bermuda we boarded H.M.L.C.H.75 and set about engine

repairs and servicing and giving her a good

scrub-over. It was with some relief and pride that we managed to steam into the Naval Dockyard

receiving many congratulations from the shore staff. The dockyard staff took

over the ship with the purpose of making her seaworthy again,

which we were told would take several weeks.

The work done we set off with other landing craft that

had arrived from the U.K., a little apprehensive that we were in the

hurricane season for this area. We had been through plenty of atrocious

weather and sea conditions so we had a 'devil me care' attitude to the

risks. All went well until we arrived

on the edge of a hurricane, still some way off the American coast.

It was no surprise when our engines started playing up again but by this time we were

used to sorting out such problems. However, after calm consideration of all

the issues, it was

decided we would be towed the rest of the way by one of the other ships.

This was not an easy task in the inclement weather.

The fact that we arrived in Norfolk, Virginia was a credit

to the ingenuity of the amateurs that made up the crews of landing craft.

These crews fulfilled some indescribable tasks in all parts of the world, in

ships that would make professional seaman cringe. In fact professionals

would have refused to sail in them. Eventually we secured alongside the jetty reflecting on

all that had happened since we received the radio message in the Indian

Ocean. I am proud to say that the ship looked immaculate, freshly painted

inside and out with all the stores and valuable items in their correct places.

She was an absolute credit to the Royal Navy. However, we were in for a rude awakening!

An American Navy officer

came aboard to receive the ship back from us. He was not interested in any

inspection or inventory of equipment, stores and armaments. His response to

my invitation was 'No thanks... she'll be saucepans in a few weeks. How much

booze have you got?' We later found out that Virginia State and the American Navy

were both "dry", so alcoholic drink was at a premium. We foolishly gave ours away, as

if our visit was an act of entente cordiale. We should have sold it to them

- an officer of equivalent rank to me was being paid three times the salary

I received. Hindsight is a wonderful thing!

The Americans entertained us well (although we took our

own booze) and this helped me to forget the hurt I had felt at their

off-hand attitude at the official handover of the ship. We found America so

very expensive on a U.K. salary so we couldn’t enjoy the goodies that were

on offer ashore. With the formalities all over, we embarked on a troop train

for New York on a long journey in one of the most horrendous trains I had

ever travelled on. We arrived in New York very tired and were booked into the Babazan

Plaza hotel until joining the ‘Queen Mary’ for our

trip home. We were shown the delights of New York, which after the U.K. and

other war-torn parts of the world, seemed completely unreal.

The Queen Mary had ceased being a troop ship so we

travelled home first class. Having spent the past years bouncing around the oceans

on small ships, there was little to do except eat and

drink. Fortunately the trip only took four and a half days but I was now well

overdue for ‘demob’.

There was no hero’s welcome for me. I passed through the

customs at Southampton without ceremony and then on a train home to Bath. It was lovely

travelling through the familiar English countryside again. After two weeks

leave I reported to HMS Roseneath in Scotland for a medical and an honourable discharge.

And that was that!

One sequel to the episode with H.M.S.Porlock Bay occurred

many years later. I was having a drink with a friend I had known for years

through ‘Scouting’. Ponta Delgada came up in the conversation. You could

have knocked me over with a feather when my friend said 'We towed a ship from there to Bermuda'. For all the intervening years we had not

known that we shared that journey!

Postscript

I have avoided writing about the many actions I was

involved with during the War since these are well documented. A lot of nastiness happened to me but I don’t think that needs telling

here. These are my recollections of this turbulent and unpredictable period of my life.

The dates

may not be completely accurate as I never kept a diary but I believe it is

important for memories like mine to be recorded for the benefit of future

generations amongst whom I hope there will be members of my own family.

These significant events, of so long ago, should not fade from

the collective mind of the public and I hope my short account here will

assist in this.

It is often said that teenagers of today would not

perform as we did given similar circumstances. This is entirely wrong in

my view since it is the circumstances themselves that create the

opportunities to serve one's country. Throughout history each generation has

risen to the challenges they faced because they were there and it was

their duty.

I deeply regret missing out on all the normal activities

of the growing up teenage years. I wore a uniform from the age of sixteen

until I was over 22. To survive in the adult world I quickly had to learn to

think and behave like an adult many years beyond my age group. Failure would

have resulted in ridicule, bullying and being socially ostracised. We had

no choice but to grow up fast. Another manifestation of the same issue was

the difficulty in adjusting to civilian life after so much travel, danger

and periods of great activity packed into the earlier years. However, I'm

sure my experiences through the war did contribute to my success in farming,

although catching up the time lost was not easy.

Skipper Ronnie Parks of H.M.L.C.T.1171 was twenty-one and

I, the First Lieutenant, was twenty. The rest of the crew were under twenty.

It certainly was a young man's war! I would love to meet any crew members of

H.M.L.C.T.1171 or H.M.L.C.H.75 to talk over old times and to thank them for

a superhuman effort and devotion to duty especially during the whole of the

D-day period.... under the circumstances of our parting the officers and

crew of 1171 had no time for proper goodbyes. After we were picked up from

the water we were taken to Southampton and that was the last time I saw the

men. I'd be delighted to hear from anyone who remembers me from the war

years.

So that's it. In August 1942, at the tender age of 18 I

joined the Navy as an ordinary seaman at H.M.S. Raleigh. I was

commissioned as a midshipman in December 1942. Apart from a short time on

the Torpoint ferry in the patrol I spent the next four years in Combined

Operations. My pay office was H.M.S. Copra and also H.M.S. Quebec

at Inveraray. After drawing cash from pay offices in various parts of the

world without any problems, at the final summing up I owed H.M.S Copra

£70... by today's standards that would be well over £1000. I joined the navy

broke, lost everything I possessed three times and left the navy broke...

but overall it was an amazing and rewarding experience which I was

fortunate to come through unscathed. In many different ways I had the

time of my life!

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our

'Combined Operations Books' page which can be purchased on-line from the

Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and paste the title of

your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's no

obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more

information.

Acknowledgments

His Majesty's Landing Craft Tank, HMLCT 1171 was

written by Austin Prosser and edited for website presentation by Geoff Slee.

The officer training was one of the most traumatic, but

beneficial, of my naval career... indeed of my whole life. It improved

my attitude and outlook for the better. The course was of necessity very

tough bordering on the sadistic... of thirty-six candidates who started only sixteen passed.

My fitness,

physique and sheer stubbornness helped me through the physical challenges. On

the 23/12/42 I walked into

Moss Bros. in London as a matelot and came out as a

Midshipman R.N.V.R. I was proud of my achievement and

subconsciously realised that I wasn't a complete moron after all. However, I always

knew that appointments like mine where to meet a particular contingency of

war and that as such we were expendable... we were a kind of commissioned cannon fodder.

The officer training was one of the most traumatic, but

beneficial, of my naval career... indeed of my whole life. It improved

my attitude and outlook for the better. The course was of necessity very

tough bordering on the sadistic... of thirty-six candidates who started only sixteen passed.

My fitness,

physique and sheer stubbornness helped me through the physical challenges. On

the 23/12/42 I walked into

Moss Bros. in London as a matelot and came out as a

Midshipman R.N.V.R. I was proud of my achievement and

subconsciously realised that I wasn't a complete moron after all. However, I always

knew that appointments like mine where to meet a particular contingency of

war and that as such we were expendable... we were a kind of commissioned cannon fodder.