|

PLUTO - the Salvage of 800 Miles

of Seabed Pipes.

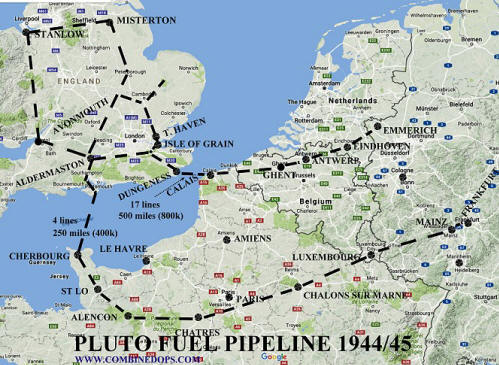

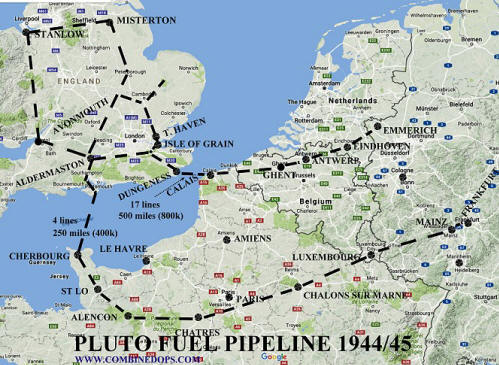

1946 to 1949

Background

The recovery of the PLUTO pipelines

was the mother of all salvage operations! - dangerous, arduous and

huge! There were 21 pipelines stretching across the English Channel

and after two years almost 800 miles were recovered for recycling.

These are the personal reminiscences of Capt F A Roughton MBE,

who was involved in the laying of the pipeline and its recovery.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data

2017].

With the cessation of hostilities in Europe the cable laying ship I was serving on, HMS Latimer, was decommissioned.

It had been involved in the laying of the PLUTO petrol pipelines across the English Channel. This was a time of great upheaval and

change, as wartime conditions gave way to peace. I was presented with two options; remain in the service and be drafted to the war still raging in

the Far East or take demobilisation. At the age of 32 my only seafaring qualification was

a 1st mate's foreign going certificate of competency, so I opted for demobilisation and a period of study for my Masters

Ticket at the University of Southampton's School of Navigation. I then considered how best to fill in the few months before the course

started.

We had little financial security, as was the norm in those days for married ex-servicemen with young families. We

had just enough money to cover our expenses while I was at University, so the need for a full-time, if short-term, job was obvious and I soon found myself

labouring at a Nuffield's metal reclamation centre some 25 miles from home. There were 15 hands, all ex-servicemen, under a civilian foreman.

I was the only seaman, the rest being ex parachute regiment and Royal Marine Commandos. Our uncomplicated task was to segregate the various

metals in a central dumping area but I was happy and carefree after the

discipline and rigours of service life and I greatly enjoyed the inter-service banter and comradeship.

Earlier than expected I received confirmation of my University place and accommodation. Handing in my notice

was however not entirely straightforward, since the job was subject to the 'Essential Works

Order Agreement' (EWOA). This legislation controlled the movement of labour for certain occupations considered crucial to the country's

recovery. Fortunately the foreman and managers were very sympathetic and they contrived to circumvent the

strict rules of the EWOA by declaring my job redundant. No doubt my job was filled after a suitable passage of time!

Our finances were still precarious but, with careful budgeting, we could fund my three months course followed by one week for the exams.

Having sacrificed so much as a family, and having put in so much physical effort to accrue the funds we needed, I had the

strongest of motives to get stuck in to my studies!!

The examinations consisted of seven written papers; Practical Navigation - 3 hours, Meteorology - 2 hours, Ship

Construction & Stability - 3 hours, English - 2 hours, Ship’s Business - 2 hours, Magnetic Compass - 2 hours, Engineering Knowledge - 3 hours and

Orals for Seamanship. The latter gave the examiners an opportunity to cover any perceived weaknesses in the written work and Signals, which

included Morse, Semaphore and the

International code of signals. It was of unspecified duration but felt like a lifetime to me!

I was given the result of the oral part of the examination right away followed a week later by the results of the

written papers. All subjects were "passed" and the sense of relief in our household was palpable....and we still had £17 in the fighting fund.

We had made sacrifices and now there was time and money, so the following Monday

we were enjoying ourselves on the beach at Saltburn-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire. The carefree abandon was not to last! My sister-in-law arrived

with a telegram offering me command of the cable-ship Empire Ridley with a salary of £80 per month - £960 a year. This was untold

wealth in 1946, so, with little hesitation, I wired back 'Provisionally accept please send further details'.

I learned later that my old commanding officer from the Latimer, Commander H Treby-Heale, RD, RNR, had recommended me to the ship-owners

when he declined the job on account of his age. The reference he wrote would have got me into heaven!

My Appointment

The next day I received a telegram with full details of the appointment and early on the Wednesday I was on the train bound for Southampton.

I met my boss and employer, Managing Director and Owner Captain J O Ingram of Marine Contractors Limited. In addition to owning the salvage firm

he was also Chief Salvage Officer to the Ministry of Supply.

Captain Ingram explained the terms of the forthcoming salvage operation but I needed no explanation about the

technicalities since I had an intimate knowledge of PLUTO from my pipe-laying days in 1944. Four vessels were to be involved, all under the

control of Captain Ingram from his Southampton Office viz.,

-

the cable-ship Empire Ridley, the ex HMS Latimer of Force PLUTO, was

to be

commanded by myself and was to be used exclusively on the recovery of the HAIS flexible pipelines,

-

the cable-ship Empire Taw - the ex HMS Holdfast of Force PLUTO, was

to be commanded by Captain Doyle. He had an interesting background having been in command of Lady Yule's yacht

Nahlyn, famous for being a favourite cruising vessel for Edward VIII and Mrs Wallis Simpson. Empire Taw was to be used exclusively for the

recovery of HAIS flexible pipelines,

-

the Empire Tigness was an ex Admiralty landing craft owned by Marine Contractors Ltd. It had a

company Coasting Master on board, which restricted its operations to the 'Home Trade' area between the Elbe and Brest. She was fitted out with special caterpillar hauling gear for the recovery of the steel HAMEL pipelines. Unlike

the flexible HAIS pipelines the steel ones could not be coiled or picked up by 'CONUN' drums and tugs,

-

the Redeemer, also owned by Marine

Contractors, was an ex Admiralty motor fishing vessel. Her task was that of diving ship plus supply tender to Ridley, Taw and Tigness. The latter role allowed the three vessels to remain on station for long periods without the need to return to

port for supplies.

I stayed the night in the Dolphin Hotel at Southampton and next morning set off with Captain Doyle for Maldon and

the river Backwater, where both Ridley and Taw were 'laid up'. Little did we suspect what we would find there!

The Empire Ridley

I'll never understand how I came to harbour the notion that I was returning to my late 'spick and span' HMS Latimer. Empire Ridley, stripped of all her Royal Naval accoutrements, was a depressing sight. She had lain unattended since

decommissioning about 12 months earlier, was thick with dirt, rusty and generally derelict. Those were my first impressions and worse was to

follow - she was infested with rats! No matter what I opened, cabin, locker, hold or engine room, a myriad of little bright eyes shone out of the gloom. The vermin made no attempt whatsoever to run away but menacingly held

their ground. In the amidships accommodation, the timber under the brass door sills was eaten away, leaving the brass strips unsupported. Cabin

furniture was also destroyed. The situation left me in no doubt as to what my first priorities had to be. After several weeks 'deratization' by

the Port Health Authorities, a thorough cleaning by local ship cleaners and refurbishment, we were ready to live on board. It had been an

unpromising start to my new command!

Crewing was also something of a problem. I had intended to immediately sign a full crew of 120 including the cable hands. However,

on advice about the suitability of labour in the local employment pool, I decided to engage only a steaming crew for our passage to Southampton. We eventually departed from the River Blackwater

and set course towards Southampton in fine, calm, clear weather. We signalled our owners details of our departure time and ETA (estimated time of

arrival) at the Nab Tower. The calculations were based on a speed of 11 knots,

which was the cruising speed of the ship when she was in RN hands as HMS Latimer.

The passage was a nightmare! We rarely exceeded a speed of 6 knots in the most favourable of conditions, with an average of 4 as adverse tides reduced

progress to only 2 knots. We were forced to anchor in Dungeness East Roads in order to wait

for suitable tidal conditions to round Dungeness Point and gain an offing from the coast. The engine room personnel were unable to raise a full head of steam

but could not explain why. I suspected clouded judgement caused by excessive intake of alcohol. Learning from experience, on leaving Dungeness East Roads

we carefully calculated the next stage of our journey based on the actual performance to carry us up to Netley Pilot Station, where pilot and tugs would be waiting to take us onward to No 102 berth in the new

docks. Despite my worst fears we arrived there safely and paid off the steaming crew. They left, as they had arrived, in a blaze of alcoholic glory!

Our new Chief Engineer identified the problem - the steaming crew had fed salt water direct to the boilers when it should

have been desalinated by the engine room condenser. We were fortunate that the furnace crowns did not collapse as a result of hot spots caused by

salt deposits.

Recruiting a crew at Southampton went well. The company, through Captain Ingram’s association with another local

salvage organisation, were able to recruit a full engine room complement of first class hands, whilst through the School of Navigation, I obtained

the necessary quality deck officers. The ship’s crew were obtained from the local shipping pool and the 60 cable hands selected, by interview,

from ex-servicemen from the Army, Navy and Marines. We were spoiled for choice and ended up with a first rate ship’s company. Meanwhile, work at berth 102 was proceeding apace with the construction of a massive tubular steel scaffolding

structure designed for discharging, coiling, and cutting up of the salvaged HAIS lines

Pipeline

disposition on the Seabed

When the pipelines were laid, there was already a desperate need for petrol to fuel the advancing Allied forces. The order of the day was

therefore to commission the fuel lines as quickly as possible (see

map opposite). Little or no

thought was given to easing future salvage operations, so it was not unusual for one line to be laid on top of others, producing something of a

tangle on the seabed. Number 1 and 2 HAIS

lines, laid from conventional cable-ships, did have a reasonable separation within the two mile wide swept channel but number 1 and 2 HAMEL lines were

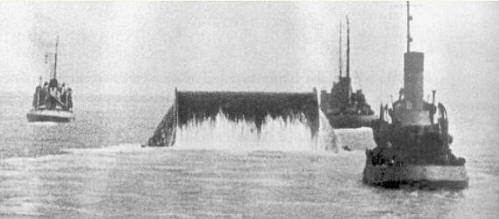

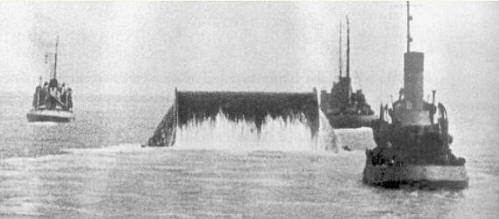

laid from the huge unwieldy floating 'CONUN' drums towed by the tugs of the HM Rescue Force (see below). This was a difficult operation with

strong channel tides causing some deviation from the intended straight course. This resulted in the flexible HAIS lines being overlaid with the

steel HAMEL lines on numerous occasions. When the pipelines were laid, there was already a desperate need for petrol to fuel the advancing Allied forces. The order of the day was

therefore to commission the fuel lines as quickly as possible (see

map opposite). Little or no

thought was given to easing future salvage operations, so it was not unusual for one line to be laid on top of others, producing something of a

tangle on the seabed. Number 1 and 2 HAIS

lines, laid from conventional cable-ships, did have a reasonable separation within the two mile wide swept channel but number 1 and 2 HAMEL lines were

laid from the huge unwieldy floating 'CONUN' drums towed by the tugs of the HM Rescue Force (see below). This was a difficult operation with

strong channel tides causing some deviation from the intended straight course. This resulted in the flexible HAIS lines being overlaid with the

steel HAMEL lines on numerous occasions.

The problem of fouling the over-riding lines was a challenge to be overcome.

Between Dungeness and Boulogne, where there were 17 lines, the fouling problem was much greater in the early stages of operations when most lines

were still on the seabed. The fouling situation improved as the number of pipes left on the seabed decreased. The salvage value was heavily in favour of the HAIS

cables with their considerable lead content and for this reason they were given priority for recovery.

Salvage Operations - Phase I

[See

Nautical

Terms

if you are unfamiliar with names used in the text]

Thursday September 12, 1946. Seaborne operations got underway: Tigness to work on the shore-ends of

the HAMEL (Steel) pipes in Sandown Bay on the Isle of Wight; Empire Taw

to commence work recovering the HAIS

(Lead) pipelines between Lepe on the UK mainland and Gurnard on the Isle of Wight, each line being some 5000 yards in length; Empire Ridley

to proceed to Sandown Bay where Redeemer, aided by her divers, would locate, cut and lift the seaward end of number one HAIS line. This done, the Empire Ridley was gently brought alongside her and the pipeline end transferred by way of

Ridley’s main forward cable hauling gear. The change-over occupied about one hour and twenty minutes before the cable end was inboard and

secured in No.1 cable tank. At this juncture the recovery work commenced, employing 20 cable hands coiling down as the huge winch drum steadily

hauled the line inboard from the seabed.

The start of operations attracted considerable press interest and the inventor of HAIS, Mr Hartley, was on board

as an observer. The weather was fine, calm and clear - ideal conditions for everyone - the hands, the cameramen and the VIPs.

We worked continuous shifts until 1400 hours on Friday September 13 (note the date) when, owing to

main engine defects requiring a complete shut-down, we came to a grinding halt. We rode to cable throughout the rest of the day and all night

until 0514 hours on the Saturday morning, when work resumed. By noon we had recovered 7.5 miles of HAIS line.

About this time the weather worsened with a force 6 south-westerly wind. There was a rough sea and heavy swell

when the wind was over the tide. Around 1700 hours the pipe came in leaking and spurting petrol in all directions. This was a surprise, since we

had been assured that the lines were petrol free having been pumped through with water. It took an hour or so to cut cable and plug the leaks

before we were able to continue heaving in.

At midnight the weather conditions increased to gale force 7-8 with a high sea and heavy swell. Ridley

rolled and pitched and shipped some water. Sunday at 0145 the pipeline parted and a number 9 crash buoy was released to mark our position. We had

recovered 12.05 miles of cable. Conditions were quite impossible for grappling to recover the cable, so we set course for the Saint Helens

anchorage. I had hoped that by continuing to slowly pick up cable that we could have ridden out the storm, but I knew then (learning the hard way)

that our policy must be to cut and buoy off in conditions of force 6 winds or greater.

Come daylight in the anchorage, we examined the bow rollers and found several bent and fractured with numerous

protruding sharp edges, which were likely to have contributed to the cable breaking. We decided, with the agreement of Head Office,

to proceed into Southampton and effect repairs. These were completed by the early morning of Saturday September 21 and at 0800 hours we

sailed for Sandown Bay to pick up the end of No 2 HAIS line.

On arrival we found Redeemer had not been able to work her divers due to bad weather and so we went to

anchorage. The bad weather continued for several days and no diving was practicable, so at 0730 hours on Tuesday 24th I decided to make a grapnel run

for the bight of No 2 HAIS. We made our first attempt at around 1025 hours and at 1047 hooked the cable, raised the bight to the bow rollers,

'stoppered' off each side of the spearpoint grapnel and cut the cable bight. We then buoyed off the shore-ward side for the shore-end vessels to

pick up and hauled the seaward side inboard. By 1440 hours we commenced coiling in wind force 3 and WSW. Remember there's a list of

nautical terms if you're a land lubber!

At 1125 next morning, the 25th September, we ran foul on one of the steel pipelines. It took

about an hour to work clear only to run foul again after about 75 minutes. This was a difficult tangle and we worked all night before

succeeding at around 0830 hours on 26th. By noon we managed to recover some 7.5 miles of No. 2 HAIS, making a

total of 19.75 miles on board. Throughout the day we ran foul of the steel lines three times, losing some 4 hours of cable recovery time. There

were unhappy faces in the cable tank as the coiling crew were on bonus. At 1125 next morning, the 25th September, we ran foul on one of the steel pipelines. It took

about an hour to work clear only to run foul again after about 75 minutes. This was a difficult tangle and we worked all night before

succeeding at around 0830 hours on 26th. By noon we managed to recover some 7.5 miles of No. 2 HAIS, making a

total of 19.75 miles on board. Throughout the day we ran foul of the steel lines three times, losing some 4 hours of cable recovery time. There

were unhappy faces in the cable tank as the coiling crew were on bonus.

On the 27th September we ran foul of the steel pipes on four occasions losing almost 17 hours of progress and on the 28th,

just before 0600 hours, we ran foul again. This time it turned out to be on No 1 HAIS that we had lost earlier. This was a tangle that took some

considerable time to clear and then only partially. While endeavouring to secure and buoy, the No 1 cable snapped. The seaward end, again

unmarked, was lost but, to the landward end, we succeeded in attaching a marker buoy, and by 1620 work resumed on the salvage of No 2 HAIS. At

1835 hours we had 25 miles of cable in the cable tank and in order to keep the ship in trim we changed to stowing in the empty tank.

All went well until around noon on the 29th September when we ran foul again - more very hard

work with no tangible rewards in the form of salvage. Eventually, at about 1300 hours on the following day we managed to raise the troublesome object. It

turned out to be No1 HAIS again. By now the pattern of the salvage operation was apparent - foul, clear, foul, clear, etc., until Friday October

4th when the weather once again turned bad. At 0500 hours we buoyed off in position 50o-12.5’N – 1o-21’W and returned to

Saint Helen’s Roads to anchor. We had a total of 43 miles of cable on board.

This was, in the main, a mundane salvage operation but there were moments of excitement and danger which are detailed

later. By the end of October Empire Ridley had 87.5 miles of HAIS cable on board, while Empire Taw and Empire Tigness

both had quantities of HAIS and HAMEL. Captain Ingram decided to bring all three craft in to 102 berth Southampton New Docks to discharge

their cargo during the worst of the winter weather period - November

through to February inclusive. Much had been learned during these first seven weeks of salvage, which would be applied in future salvage work. The Ridley's

cable hands were employed on discharging and coiling duties, while

the ship’s crews were employed carrying out routine care and maintenance.

Winter Shore Operations

- Recycling of Materials

The numerous cable ends protruding from the coils give a good indication

of the number of times the lines had to be cut and plugged when, for one reason or another, they had become fouled on the seabed. When the coiling

to shore was completed, our next task was to ensure the lines were cleared of petrol prior to being passed through the guillotine, which cut the

pipe into lengths to fit easily into the railways wagons waiting below the cutting machine loading roller-ramp.

In turn, each length in the coil was connected to a water supply at one end, whilst the other end was fitted with

a flexible pipe leading direct into a mobile petrol bowser tanker. Water was then turned on, pushing the petrol from

the pipeline into the bowser

until the operator reported only water coming through. The contaminated petrol was then taken by road to a special Ministry depot for separation

treatment to obtain clean fuel. By this process 66,000 gallons of good fuel was recovered.

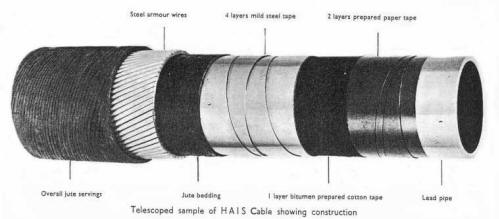

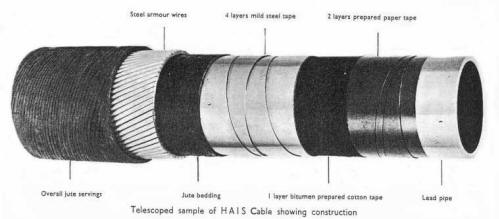

The cleansed cable was passed over the hauling gear on the discharging gantry and then, via the cable transporter

gear, to a roller arrangement. This led into a heavy duty guillotine, which cut the cable into exact lengths to fit the railway wagons. This done,

the lengths fell to a roller ramp, which delivered them to the waiting rail-side wagons for onward journey to Swansea. There, a Ministry of Supply depot was established to provide work at an unemployment black-spot. Each length was broken down in the first place into lead, armour

wire, steel pressure tapes and even the outermost layer of string-like jute yarn 'serving.' The reclamation process comprised the following operations; The cleansed cable was passed over the hauling gear on the discharging gantry and then, via the cable transporter

gear, to a roller arrangement. This led into a heavy duty guillotine, which cut the cable into exact lengths to fit the railway wagons. This done,

the lengths fell to a roller ramp, which delivered them to the waiting rail-side wagons for onward journey to Swansea. There, a Ministry of Supply depot was established to provide work at an unemployment black-spot. Each length was broken down in the first place into lead, armour

wire, steel pressure tapes and even the outermost layer of string-like jute yarn 'serving.' The reclamation process comprised the following operations;

-

the lead was melted down into ingots,

-

the armour wires passed through a simple machine, which straightened them out into rod iron for use in

reinforced concrete work,

-

the steel tapes passed through an acid bath to clean them, then to another machine operated by girls,

which flattened them into strips,

-

the flattened strips were pressed to produce metal corners to reinforce heavy duty cardboard boxes,

-

the messy

jute yarn was compressed into blocks for use as furnace fire fuel.

Salvage Operations - Phase II

On the morning of Feb 21, 1947, we recommenced the seaborne salvage work but fog and snow forced us to anchor in the Man of War anchorage off Spithead.

On the 22nd, we moved anchorage to St. Helens Roadstead off the Isle of Wight to wait favourable

weather conditions. We finally started the second phase of the salvage operation on the 24th February, 1947 by picking up our marker buoy in a position 179.5o degrees 15.3 miles from

St. Catherine’s Point. In general, proceedings followed those of our earlier operation - recovery, fouling, recovery, fouling, cutting,

buoying off and running for shelter. Each time we cut a fouling steel pipe we buoyed off both ends, so that Tigness and Wrangler could

recover the pipes before the buoys were lost to passing ships. On one occasion, all our buoys were in use or in transit, so we used 40 gallon oil

drums as an interim measure until MFV

Redeemer replenished our stock.

Our makeshift marker buoys had a tendency to 'run under' due to strong tides and the weight of the mooring wire.

Under these conditions they collapsed under the pressure of water, lost buoyancy and disappeared below the waves never to be seen again! Working in fairly deep water required the use of long

lengths of heavy mooring wire, so two, or even three, oil drums were needed to

ensure positive buoyancy under all conditions. The standard No 4 cable marker buoys had bulkheads to prevent collapse but the No 9 type, often

used as steel markers, had no bulkheads and also ran under from time to time. However, they were much stronger than oil drums and only on rare

occasions failed through metal collapse.

By April 12th, 1947, 53.2 miles of HAIS cable had been recovered from the Cherbourg to Isle of Wight

circuits number 1 and 2, making a total recovered, by Empire Ridley, of 140.7 out of about 144 miles originally installed. Our job done in

that area, we received instructions to make for the Dungeness/Boulogne area to continue salvage duties until we were fully loaded. Empire Taw, Tigness and Wrangler,

already working in that area, were experiencing serious problems due to cable fouling made worse by inaccurate plots of the positions of the

pipelines on the seabed. This was a matter of some concern to the company, since very

little cable was being salvaged during these periods of disruption. Crudely expressed, they were spending without earning - a state of affairs no

company can sustain over a prolonged period.

Empire Ridley arrived off Dungeness at 4am on April 13th. It was

a misty morning and only the Dungeness High Light was available for compass bearings, so we decided to wait for daylight before dropping our

marker buoy to signal grappling operations. I was confident of our position to pick up

the No 17 line, which was the final HAIS cable laid from HMS Sandcroft. At 0720 hours we dropped a No 9 marker buoy in position

Dungeness High Light bearing 306o at a distance of 3.2 miles. We then awaited the turn of the tide to allow us to make a correct line of approach

for the initial grapnel run.

At 0923 hours we let go the spearpoint five prong grapnel and made our first pass by 0940. This completed, we stopped and hove up to find the grapnel empty.

As is often the case with fishing, we had felt a tug on the line during the run but the cable had gone slack again - a possible near miss. By 1010

hours we were back in position and commenced our

second run at a slightly reduced speed. At 1030 hours we made a contact and commenced heaving in the heavy wire. At 1047 hours the grapnel

broke surface with a single HAIS pipe hooked on two prongs. It was possible to identify

the ship that laid the pipe from the type of bitumen compound 'lutin' used and the length of the lay of the armour wires. Confidence was high

that we had located the pipeline we sought and we

cut the bight, after first holding each side of the cable in stoppers from the forecastle head.

The shore leading leg showed very little tension, an indication that it was a 'short end'. The seaward leading

leg was taken to the starboard main winch drum and hauled in until the end could be secured in the cable tank. Our suspicions

about the shore leading leg were confirmed when 100 yards of pipeline were easily dragged home. There were signs that it had been cut by

hacksaw and after stripping down a short piece, the manufacturers name tape confirmed our earlier armour and lutin check. We had indeed found our target cable.

The Managing Director of Marine Contractors was a very keen fox hunting man and a member of his local hunt. We

signalled our success and imminent progress in the Dungeness Boulogne area with the signal "Yoikes Tallyo" and started to haul away towards

France. This was the last of the pipelines to be laid down so was free of snags and it was the only line salvaged that didn’t run foul of other lines. However, off Boulogne,

the pipeline ran into the Bassure De Baas sand bank. We hauled bar tight and used the rise of the bows on the swell for increased lift but in the

end we were obliged to cut, proceed to the French side of the

sand bank, re-grapple and lift the line from the Boulogne shore. We followed similar procedures until once more running foul in the sand and

again abandoning the cables across the width of the sandbar. In due course we found that some of the pipelines had become so deeply embedded in

the sand that our hauling gear could not pull them out despite our best efforts.

We experienced a similar problem close to a position south of the ridge of Le Colbart Bank in mid channel. On

this occasion the pipeline was not so deeply embedded in the sand and mud and the procedure worked well, allowing us to recover all the pipeline from that locality. However, it resulted in a mile of very slow progress but this

was, nonetheless, infinitely better than having to cut and re-drag with the high risk of hooking the wrong cable in the new location.

We still had storage space onboard for pipeline, so we moved back to the English side to find a good target position for an original hooking

of No 11 cable. This was the penultimate HAIS line laid by HMS Sandcroft. From the known order the pipelines were laid, it was likely

that the number 11 HAIS would be fouled by steel HAMEL pipes numbered 12 to 16. However, once more good intelligence from the laying

operation proved its value. We still had storage space onboard for pipeline, so we moved back to the English side to find a good target position for an original hooking

of No 11 cable. This was the penultimate HAIS line laid by HMS Sandcroft. From the known order the pipelines were laid, it was likely

that the number 11 HAIS would be fouled by steel HAMEL pipes numbered 12 to 16. However, once more good intelligence from the laying

operation proved its value.

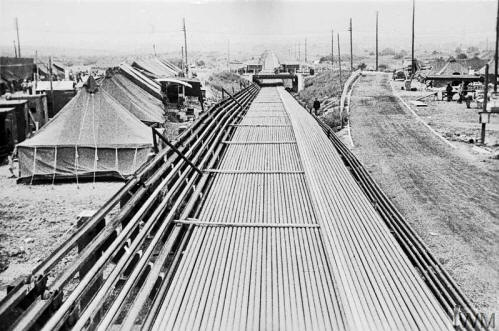

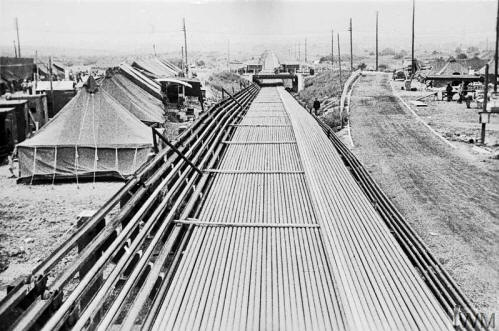

[Photo;

Laying the pipeline: Steel pipe being stored in three quarter mile

lengths before being wound onto the 'Conundrum'.© IWM (T 31)].

Working as before on a

single bearing and sextant angle on Dungeness High Light and using a No. 9 buoy with mushroom anchor mooring for a data marker, we found our

target on the third grapnel drive. It was a good start but as expected No 11 ran foul of the steel pipelines on numerous occasions. But on one

particular night we were due for a big surprise!

Around 2am, an

"all stop" whistle signal was heard from the bow cable look-out man. To our amazement, right up under the bow rollers, and just awash, was a

German fighter aircraft minus its cockpit cowling. The cable was snagged on the port wing and had torn half way through as far as the main strut of the wing. At first we

were tempted to salvage the plane but the only derrick

capable of lifting the weight was set up and rigged for other uses. Un-rigging and setting up the necessary double purchase gear was a fairly

lengthy operation but there were other reasons for caution too - there was no convenient stowage space

available and we had no idea of the quantity and state of any munitions still within the fuselage and wings - an unacceptable fire risk with

petrol spillages from the recovered pipes within our cable tank. That decided, we had to return it safely to the deep.

We hauled in cable and drew the fouled port wing right up under the bow rollers in the hope that the rest of the

plane would break off and fall away under its own weight. It worked a treat. With scarcely a sound the main wing beam broke and the plane slid back to Davy Jones’ Locker. We were

once again free to get on with money making salvage work. For reasons of their own, Head Office endorsed our decision by noting that "the value of the salvaged plane was

very low and its nuisance value in Southampton Docks would have been correspondingly very high".

The completion of the salvage of this second HMS Sandcroft laid cable brought our cargo to 102.2 miles of

3" HAIS cable - just a little over the design capacity of our two cable storage tanks. We left the salvage site for Southampton to discharge

our cargo, leaving

Empire Taw working on the shore end HAIS lines off Dungeness.

Occupational Hazards

On a number of occasions when trying to clear a fouled cable, we hove up our spearpoint grapnel to find moored

mine wire in the flukes. When there was weight on each side, it was prudent to assume we had lifted both the mine and its plummet weight off the

seabed. In these circumstances it was not a good idea to cut and let go the wire for fear of explosion! Instead a wire 'preventer' was lowered from each side of the

ship’s bows and, with seamen working from Bosun’s chairs, the preventers were clamped to the mine wire almost at water level, one each side of the bight in the grapnel fluke. The

stoppers were hove tight and made fast to the forecastle head bollards and then, with the hands back inboard, the grapnel was lowered to clear

the mine wire bight before being taken inboard out of the way. Next the two stopper wires were slacked away gently at the same rate until the

weight came off, indicating mine and plummet weight were back on the seabed. The stopper wires were then cut and allowed to sink to the bottom.

Our caution and respect were borne out of an understanding of the mine's mechanism. Some moored minefields were

designed to float just below the surface for a specified period, after which they sank to the bottom. The casing of the mine was fitted with a

soluble plug which, after the set time, would dissolve and allow water into the casing thus sinking the mine. With the weight removed from the

plummet sinker the fail safe device would operate, rendering the mine inert. However, we were concerned that mines caught up in our gear had been

reactivated. The fact you are reading this

indicates we were very lucky or our justified fears were groundless… or perhaps the rabbits foot in my pocket was doing its job!

At other times fouling was caused by wreckage on the seabed. On more than one occasion the grapnel wire came

bar tight and brought the winch to a grinding halt. Slacking back the wire and allowing the ship to fall back on the tide sometimes freed the

grapnel but on other occasions we made the wire fast on the forecastle bollards and used the ship’s engines, ahead and astern, until we came

free, shifted the wreckage or broke the grapnel prongs off! On one occasion we even broke the heavy duty 6 x 3 compound wire, thus losing the

grapnel. By the curse of Murphy’s law it was almost invariably during the hours of darkness that these various hold-ups occurred! As we gained experience we could tell from the note of the hauling winch engines that we were running foul of

the steel pipes. Gradually the normal operating note of the engines would be replaced by an increasingly higher pitched whine as the winches

laboured under the extra weight of the steel pipes. By the time the HAIS pipe was hove inboard it would begin to twist and flatten on the bow

rollers. It was time to start clearing operations.

There were dangers in the recovery of the HAIS pipelines but the recovery of the HAMEL steel pipes was in

a different league! Having secured an end onto the deck, the line was hauled aboard by means of a

horizontal caterpillar machine on the fore-decks of Tigness and Wrangler. A system of rollers abaft of the hauling gear, and running the

full length of the working decks, allowed the cable end to be taken as far aft as possible. Once in place, the pipe was cut into suitable lengths

and then transferred from the rollers to a stowage area on the working deck... and so the process would start all over again.

Each length of HAMEL cable was cut just aft of the caterpillar by means of oxy-acetylene burners. However,

there were still pockets of petrol/gas at very frequent intervals and the hands were equipped with

fire and flash proof gear against the numerous bursts of flame and gas flashes. Often

petrol leaked from the pipes and despite our best efforts was not washed away from the decks. From time to time patches of fire occurred on

board.

The decks were kept wet at all times by means

of pumping water from the ship's ballast tanks. There was also an

additional hazard, less threatening to the ship and its crew but quite spectacular in its own way. Sometimes petrol leaked whilst the pipe was

still outboard and formed a film around the ships. Inevitably sparks from the burners caused the inflammable film to burst into flames. It was an

uncanny sight as the fire around the ships passed clear on the tide and burned itself out astern. The crews of the two vessels seemed to treat

the matter as just part of the job, nevertheless, whenever Empire Ridley was working in sight of either or both ships, it became standard

practice to call them on radio telephone to ensure all was well.

The Outcome

The general routine of the work was similar on both the HAIS and HAMEL recovery ships - operating at sea

during the period March to November and in port between November and March discharging, cutting and loading salvaged cable to railway wagons for

onward transit to Swansea. By late 1949 a total of 478 miles of HAIS cable had been recovered from a total of about 482 miles laid, and around

300 miles of HAMEL out of some 330 miles installed had been recovered. Salvage operations were concluded. In October 1949 all the cable landed at

Southampton was cut up and delivered to Swansea and work commenced dismantling the site at 102 berth. The value of the salvaged material we were informed was

considerably in excess of recovery costs. This no doubt provided the Ministry with a handsome profit as well as creating work for a few years in an

unemployment black-spot.

The Empire Ridley was sold to Spanish owners, Empire Taw to the Irish Lighthouse Services,

Tigness and Wrangler with Redeemer remained with Marine Contractors Limited to continue the company's marine salvage work. The

crews of Ridley and Taw were paid off and dispersed, almost all securing berths in various liners out of Southampton. I had the

good fortune to get an immediate appointment as Marine Superintendent in Messrs Siemens Brothers of Woolwich, Submarine Cable Department. I had

an excellent and effective crew and when we parted I had mixed feelings - glad we had successfully completed the project but sad to say goodbye

to men I admired and respected

Even under normal operating conditions our work was fraught with danger, as enormous forces were at play. These

dangers increased dramatically when we were dealing with unknown objects, unexploded mines, fouled lines and petrol spillages. Despite the

dangerous nature of the work, often undertaken in rough sea conditions, there were thankfully no serious casualties. The successful completion of

the salvage operation is a lasting testimony to the bravery, skill and dedication of the officers and men involved.

Nautical Terms

A Spearpoint Grapnel is essentially a huge 5 pronged spinner type fishing hook. Each prong is called a

fluke. The Grapnel used in the recovery project weighed in at around 2 to 3 cwt and was attached to a powerful winch by a

special rope.

The Cable Bite was that part of the pipeline, in the shape of a curve or loop, raised from the seabed by

the Grapnel to the level of the ship's deck.

A Stopper is

ashort length of rope, wire or chain attached to a taut line or mooring rope to take the

tension in the line or rope while it is, for example, made permanently fast on the ships deck.

A Bollard is a heavy duty solid metal post on a ship or dockside to which ropes or wires can be securely

anchored.

Plummet Weights are heavy anchoring devices to hold sea-mines in position just below the surface, which

would otherwise float on the surface. Under tension the mooring wire holds the mine's firing mechanism in the live position, thus ensuring an

explosion in the event of a ship colliding with it.

A Wire bight is a general description for that part of a rope or wire held in the shape of a loop.

A Bosun's Chair is a seat suspended from a cradle of 4 ropes attached to a line. This can be lowered over

the side of a ship to allow seamen to work safely on, for example, painting duties.

A Bowser Tank is a towed trailer (not unlike a trailer of an articulated petrol tanker), which can be left

on site by its towing vehicle.

A Bowser Tanker is a self-propelled tank vehicle loaded and unloaded with the driver in attendance.

Bulwarks are areas of the main or upper decks, which are protected by permanent solid steel plating as opposed to

railings which, in areas normally used for loading, were removable.

Further Reading

On This Website;

PLUTO,

PLUTO in Fawley &

PLUTO Pipe Manufacture.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more

information.

PLUTO - World War 11's Best-Kept Secret by Bob Knight, Harry Smith & Barry

Barnett. Published in 1998 by Bexley Council. Softback, 34 pages with many

illustrations about the involvement of The Callender Cable Co.

PLUTO - Pipe-line under the Ocean by

Adrian Searle. Publisher Shanklin Chine, 12 Pomona Road, Shanklin, Isle of

Wight PO37 6PF. ISBN 0 9525876 0

(Description of book. To many in WWII it

seemed a preposterous idea - an undersea pipeline laid across the bed of the

Channel to carry fuel to the Normandy beaches. It was carried out in absolute

secrecy &, according to Eisenhower, it was "second in daring only to the

artificial 'Mulberry' Harbours.' The extraordinary project, & the millions of

gallons of fuel it carried, helped to ensure that the Allied armies could

break out after D-Day. 126pp, photos, ills, maps).

National Archive, Kew, London

Some records on

PLUTO are available to be

viewed (personal callers or paid researchers only - NOT available on line). You

may find others by visiting their Online

Catalogue. Copies of documents can be ordered on line.

Correspondence

(10/04) Dismantling of PLUTO in Greatstone,

Kent. I observed the dismantling of PLUTO in 1947 from where I lived at the

time... Greatstone. Although I was only 6 years old then, I remember the pioneer

tracks being laid from the area adjacent to the "Jolly Fisherman". It was all in

the local paper, so I think it should be possible to get something from local

archives. Somebody painted on the rusting hulk of the main container "Stuck like

Atlee". There must have been many hitches and hold-ups because some weeks later

someone painted "Still stuck like Atlee" on the partially dismantled but still

substantially complete container. Peter Briody.

Acknowledgments Acknowledgments

These are the personal reminiscences of Capt. F A ROUGHTON M.B.E.

who was Master of one of the main vessels in the salvage of PLUTO after the war. To read an account of the wartime planning, design, manufacture, testing and installation of the

pipelines visit Operation PLUTO

|