RAF

Air/Sea Rescue - A Top Secret D Day Mission.

Background

For a select few, serving in the RAF Air Sea Rescue

Service, D Day found them undertaking an important, top secret task which

would improve the chances of survival of thousands of servicemen . It was so

secret, the crews did not fully understand the nature of their work until they were in

position off the Normandy beaches.

For a select few, serving in the RAF Air Sea Rescue

Service, D Day found them undertaking an important, top secret task which

would improve the chances of survival of thousands of servicemen . It was so

secret, the crews did not fully understand the nature of their work until they were in

position off the Normandy beaches.

[High Speed Launch (HSL) 2665 in action. Similar

craft appeared in the 1954 film "The Sea Shall Not Have Them", which is

available free on Youtube].

In March 1944, five RAF skippers were selected from the British

Isles Air Sea Rescue Service for a Combined Operation on D-Day. The skippers

were given a freehand to pick their crews from any unit they wished. My skipper,

Flying Officer (F/O) W E Probert, was one of the five chosen. I

had served with him as a wireless operator / mechanic for some time.

F/O Bill Probert had risen from the ranks and was highly

respected by all who served with him. He was a man of few words, who led by

example. We came from No 48 Air Sea Rescue Marine Craft Unit (ASRMCU) at

Tenby, as did another Skipper, F/O Ambler.

The two crews were given new Thornycroft High Speed Launches, which had their armament upgraded for the

operation. The three .303 machine guns, located in their manual turrets, were

replaced aft by a 20mm Oerlikon. The tops of the port and starboard turrets were

removed and .5 Browning machine guns were installed.

Preparations

Preparations

Our duties at Mount Batten, from March until June

1944, were those of

any Air/Sea Rescue unit but with the addition of

frequent gunnery exercises in the English Channel. We were on duty 24 hours a

day, for 4 days running, living onboard in cramped conditions, except for meals

ashore. The fifth day we had off duty.

[Photo;

the author, veteran Clifford N Burkett].

Such was the secrecy, that we were not given any details of our D

Day mission. Two days before D Day, a white star was painted on the foredeck by

the deckhands and immediately covered for security reasons. A white star was

painted on all aircraft, vehicles, vessels, tanks etc. so any vehicle, aircraft

or vessel without a star, was treated as the enemy. The Skippers, Wireless

Operators and Cox'ns met in a hanger, guarded by the RAF Regiment with fixed

bayonets. The purpose was to provide a minimal briefing to the coxswains and

wireless operators, who were given new wireless frequencies and call signs. Only

the Skippers were given more information.

Our HSL was numbered 2655, F/O Ambler's was

2653 and the others were 2512 & 2513. The fifth, on the day, was "up the slip

for repair". The choice of the launch class was a disappointment to those of us,

who had previously served on the faster and superior HSLs built by the British

Power Boat Company at Hythe. However, speed was not the only characteristic

needed for the operation. Thorneycrofts were slightly bigger and able to

accommodate more aircrew and para survivors.

En Route to Normandy

En Route to Normandy

We assembled at RAF Mount Batten, No. 43 ASRMCU, Plymouth,

where we were joined by 3 other selected RAF High Speed Launch (HSL) crews. From

there, our 4 serviceable HSLs dropped their moorings at 3.30 pm on the afternoon

before D Day, with extra dinghies lashed on decks.

[Google Earth map].

We were joined by 3 RN Motor

Gun Boats (MGBs) from Devonport, while we were still in Plymouth Sound. D Day had

been postponed for 24 hours because of bad weather. Unfortunately, most of the troops

had already spent an uncomfortable 24 hours on board their craft.

After sailing

out through the Plymouth Hoe boom, we saw a number of landing craft tossing about

at anchor in Cawsand Bay. "Poor bloody infantry" sprung to mind, for they still

had to cross the Channel in rough weather, disembark, wade ashore and fight

their way off the beaches early the next morning.

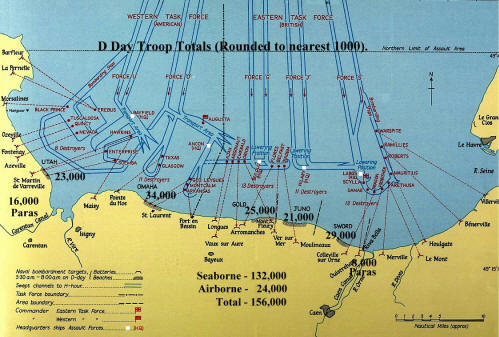

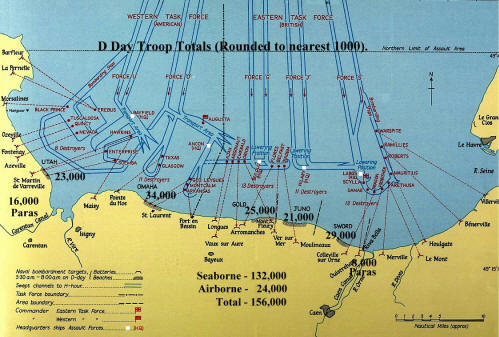

Part way across the Channel by a circuitous route, all but one

of the MGBs left us. We arrived off the coast of Normandy at 11 pm. Half an hour

later, the RAF launches and the RN MGB, switched on their search lights, which seemed an

odd thing to do in hostile waters. However, it soon became clear that the first

part of our first mission was to act as light beacons to guide in the USA 82nd

and 101st Airborne Divisions, comprising 5,000 men, to be dropped behind

the Omaha & Utah beaches.

With 5 launches, any losses due to enemy action or breakdown

would be compensated for and the additional fire power of the extra craft would

provide added defence against anticipated E Boat attacks. Around midnight, we

witnessed the huge bombardment of the coastal defences by the Allied Air Forces.

While it lasted, the coastline was a wall of flame as far as we could see, such

was the intensity of the exploding bombs.

We maintained station all night but,

because of tidal drift, had to sail back 2 or more hundred yards every 20

minutes or so, in order to maintain our exact position. The noise the 5 vessels

made when restarting their engines each time, was deafening and we worried that

the enemy would be alerted. We would have been a poor match for the German E

boats, which we knew regularly patrolled the whole of the Normandy coast every

night. Fresh in our minds was the

death and destruction they had wreaked only a few weeks earlier, when over 700

USA soldiers and sailors were lost off Slapton Sands during a training exercise called

Operation Tiger.

We expected to be fired at from the sea

or the shore at any time but, thankfully, this did not happen. I was on wireless

telegraphy (W/T) watch, 2 hours on and 2 hours off. I still have my W/T log book

with all times recorded. When not on W/T watch, I was on deck, even although we had to keep watch on two radios, (W/T & VHF). I had fitted up a Standard Beam Approach "mixer" box in the wireless

cabin. It was an unofficial arrangement approved by the Skipper. With the mixer

box, the signals from the two receivers could be fed into one operator's

earphones, but could also be separated, as required.

We expected to be fired at from the sea

or the shore at any time but, thankfully, this did not happen. I was on wireless

telegraphy (W/T) watch, 2 hours on and 2 hours off. I still have my W/T log book

with all times recorded. When not on W/T watch, I was on deck, even although we had to keep watch on two radios, (W/T & VHF). I had fitted up a Standard Beam Approach "mixer" box in the wireless

cabin. It was an unofficial arrangement approved by the Skipper. With the mixer

box, the signals from the two receivers could be fed into one operator's

earphones, but could also be separated, as required.

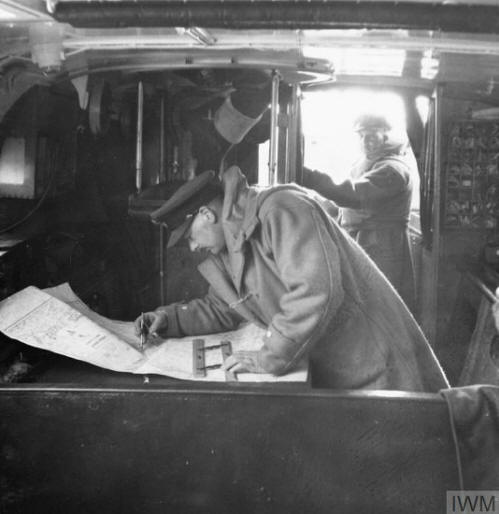

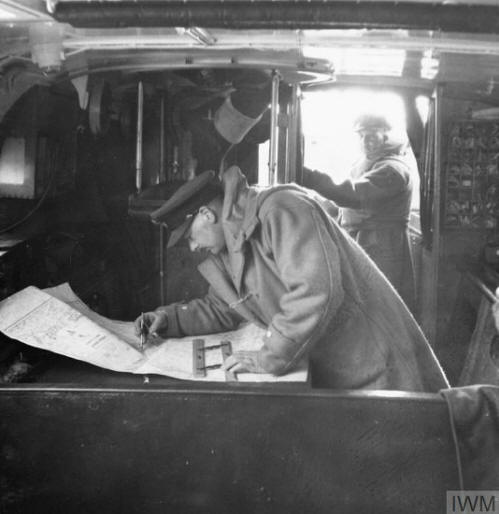

[Photo; The interior of a High Speed Launch

based at Dover, Kent, showing the navigation officer in the foreground

working out his course, watched by the Master. © IWM (CH 2498)].

We were on strict "W/T silence",

so as not to give our position away to the enemy and if messages came in on

either receiver, the Operator on watch could recall the other one if required.

Another advantage of this arrangement was that it allowed one of the W/Operators

to accompany F/O Probert on the `bridge' to man the signalling lamp.

Shortly after the bombardment of the

enemy's coastal defences, aircraft carrying 'paras' and others towing gliders,

flew directly over us. In my periods on deck, I witnessed 17 such formations fly

overhead. In his turns, Bob Bell, the other wireless operator, saw similar

numbers. It was an inspirational sight, as they flew in formations of up to 50

aircraft, with all navigation lights on. We marvelled at the skill of the pilots

in keeping such tight formations.

The Mission

The Mission

At 0530 am, before the beach landings

began, we switched our lights off and the Royal Navy MGB left us for other

duties. We sailed round to the western side of the Cherbourg Peninsula, where I

received coded W/T messages instructing us to search among the Channel Isles

for a Wellington bomber and a fighter aircraft. They had apparently ditched in

that area the day before. We split into two pairs and searched between and

around Jersey and Guernsey but after many fruitless hours searching, we returned

to Plymouth because we were running dangerously short of fuel.

The Germans were,

by now, well aware of our presence since, a Ju 88 from Jersey, flew overhead but

thankfully ignored us. We had been at sea for over 30 hours sustained only by one can

of self heating soup and adrenalin. The deck crew of 4 had manned the two

Browning machine guns and the Oerlikon, for the whole time. Their eyes were

strained, red and sore from the constant lookout they kept and by the sea. As we moved

out of the immediate danger area, exhaustion overtook them in particular, although

we were all very tired.

Most of the 5,000 airborne troops we

guided to their `drop zones' landed safely, although a number were scattered.

There were, of course, many losses but the survivors later joined up with their

comrades, as planned, who landed on Omaha and Utah beaches. We learned, several

years later, that the fighter aircraft we had searched for was found on the

seabed with the body of its Canadian pilot still on board. His widow requested

that he be left there, in the aircraft, as his grave. To my knowledge, no trace

of the Wellington was ever found.

Postscript

The day following our return to RAF

Mount Batten, we learned that not a single Allied aircraft had come down in our

area during the time we were at sea. Had any ditched, our orders were to stay on

station.

The day following our return to RAF

Mount Batten, we learned that not a single Allied aircraft had come down in our

area during the time we were at sea. Had any ditched, our orders were to stay on

station.

[Photo; Oblique aerial photograph taken during the

rescue by an RAF high speed launch of the crew of a US Navy Consolidated

Liberator on the day after they were shot down by Junkers Ju 88s in the Bay of

Biscay. A 67-ft Thornycroft High Speed Launch, HSL 2641, approaches the dinghies

containing the survivors. © IWM (C 4159)].

Some years later, at one of our reunions, we learned that captured

German records had disclosed that the regular nightly patrols of E boats along

the Normandy coast were cancelled for that night by the German Navy Officer

Commanding at Cherbourg, because " the weather is too bad for the enemy to

invade tonight!" The Germans had underestimated our seamanship in the rough sea

conditions. Our unit's mission could not have gone better and was a triumph of

meticulous planning and training.

I attended the 64th anniversary of D

Day in June 2010 with the Normandy Veteran's Association. It was a typically

British occasion, restrained and well run with speeches of thanks and

remembrance by local Mayors. The French presented us with badges of

Remembrance, the "Normandie Memoire". Several widows, wearing their husband's

decorations, accompanied us and many of those present, both men and women, wore

badges bearing a photograph of the Queen. This, apparently, because of the French

Government's snub at not inviting Her Majesty to the commemorations. However,

locally we received a very warm welcome from the people of Normandy. It was a

bitter/sweet occasion. On the one hand, it brought back memories of school

friends and RAF comrades, who gave their lives and on the other, I was glad I had

been able to honour their memory and sacrifice.

The memory of those who served in the RAFVR in the various

fast rescue craft is immortalised in the especially commissioned painting

"Combined Operations - A Normandy Beachhead". A rescue craft can be seen plying

the waters off a Normandy beach in search of any service personnel in the water.

See the painting here.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Clifford N Burkett

for this account and for the photograph of HSL 2655, on which he served. The

photo was taken a few days before D

Day during a gunnery exercise. Clifford served in the RAF

Volunteer Reserve for 5 years, three of which were in the Air Sea Rescue

Service. Sadly, Cliff passed away in August 2013.

Preparations

Preparations