|

US Landing Craft Tank (Rocket) 439 - US

LCT (R) 439.

A British Built

Rocket Craft Crewed by

US Navy Personnel on D Day

_small1.jpg)

Background

United States

Landing Craft (Rocket) 439 - US LCT (R) 439, was

a specialized landing craft, which carried 2896,

5 inch x 4 feet (127mm x 1.2m) explosive rockets designed to soften up

enemy coastal defensive positions immediately prior to the landing of the

initial assault troops.

[Photo; US LCT 439 with the racks of rocket

holders clearly visible. From Becky Kornegay, whose father, Quaver Stone

Stroud, served on the craft].

Her Commanding

Officer was Lieutenant (jg) Elmer H Mahlin and his 2nd in Command was

Ensign George F Fortune, the author of the first part of the craft's story

(photo below right). The second part gives the Commanding Officer's

perspective, as compiled by his son, Stu, from the contents of his

father's old sea chest.

%20439%20ensign.jpg) Training

Stateside Training

Stateside

On leaving college,

George Fortune volunteered for service in the United States Navy. In 1942,

at the age of 22, he attended Midshipman School at Furnald Hall, Columbia

University, New York City, for three and a half months. Furnald Hall

was one of 3 halls at the University used by the US Navy. Students stayed

weekends in local households, by invitation, enjoying home comforts, tea

dances and excursions to places of interest.

He graduated in the

top 15% of the 1000 students on the course and, as such, was allowed to

choose his first posting to Section Base on Treasure Island, which was

close by the world famous San Francisco bridge and to his home!

For 6 months he

learned ship handling, including 3 months at sea on Errol Flynn's

sailboat, "Zaca", 700 miles offshore. As the new ensign aboard, George

undertook the full range of duties of the deck crew,

including ship handling and climbing up the rigging to the top of the

mast!

With sea skills behind him, he was posted to Miami to learn

the duties of radio officer. It was a very hot journey and en route he was

taken to a hospital in Chicago for a fever check-up, which turned out to

be mumps. By July, 1943, he found himself in Miami at the Subchaser

Training Center and, after 3 month's practice in radio work and ship

handling, he reported to the Gunfire Support Craft Group in Boston, Maine,

for training in the use of various guns.

Training UK

During Thanksgiving week of 1943 (late November), he sailed to Scotland on

the Queen Elizabeth. Because of her high cruising speed of around 33 mph

(53kph), she travelled alone, usually carrying

20,000 soldiers and sailors. US Navy officers stood watch at night. Their

primary purpose was to enforce blackout regulations by guarding against

any stray light. All parts of the ship were visited during a typical watch

including the conning tower, engine room and the

occasional visit with the Captain. Lots of men were sea sick choosing to

remain below deck.

On

arrival in Scotland, he was stationed at Roseneath Castle on the Firth of

Clyde near Glasgow. Roseneath was commissioned on the 15th April, 1942,

and named HMS Louisburg. However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor

and direct American involvement in the war, the base was paid off on

3/8/42 by the Royal Navy and handed over to US control as an amphibious

training centre. On

arrival in Scotland, he was stationed at Roseneath Castle on the Firth of

Clyde near Glasgow. Roseneath was commissioned on the 15th April, 1942,

and named HMS Louisburg. However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor

and direct American involvement in the war, the base was paid off on

3/8/42 by the Royal Navy and handed over to US control as an amphibious

training centre.

[Photo; US LCT (R)

439 with the sloping racks of rocket holders just visible to the left.

From Becky Kornegay, whose father, Quaver Stone Stroud, served on the

craft].

It was used during

preparations for the landings in Vichy French North Africa in November,

1942. By 1943, following the success of the North Africa landings,

Roseneath returned to British control as HMS Roseneath. However,

sections of the base were retained by the US Navy for a 'Seabee'

maintenance force and berthing/supply facilities for the depot ship,

USS Beaver

and the boats of US Navy Submarine Squadron 50.

The officers and men

lived in Quonset huts (similar to Nissen huts), each accommodating 20 men

or so. Officers had one hut to themselves and the crews occupied the

remainder. They slept on bunks with blankets and sheets and ate in a mess

hall where, once more, officers and crew were separated. The accommodation

was comfortable and clean, though somewhat damp from condensation and "the

food was basic and typically British with only cabbage, potatoes and

Brussels sprouts for vegetables, mutton for meat, no milk except canned

and dessert rarely. Pretty grim! It was so sparse and military there, even

the hard toilet paper had 'government issue' stamped on each sheet!"

Roseneath

Castle was quite isolated, so the ship's crews mostly stayed on the base.

Officers were permitted to venture outside the base for the purposes of

sightseeing. However, it was not always the case as George recalls;

"together, with a couple of crew members, we took small boat trips from

our base at Roseneath Castle to call on our big ships anchored in the

area. We bummed anything that we could beg, borrow or beg louder for. Roseneath

Castle was quite isolated, so the ship's crews mostly stayed on the base.

Officers were permitted to venture outside the base for the purposes of

sightseeing. However, it was not always the case as George recalls;

"together, with a couple of crew members, we took small boat trips from

our base at Roseneath Castle to call on our big ships anchored in the

area. We bummed anything that we could beg, borrow or beg louder for.

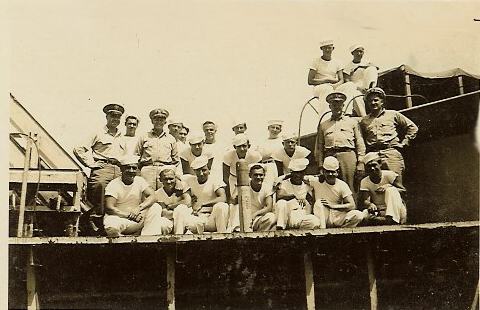

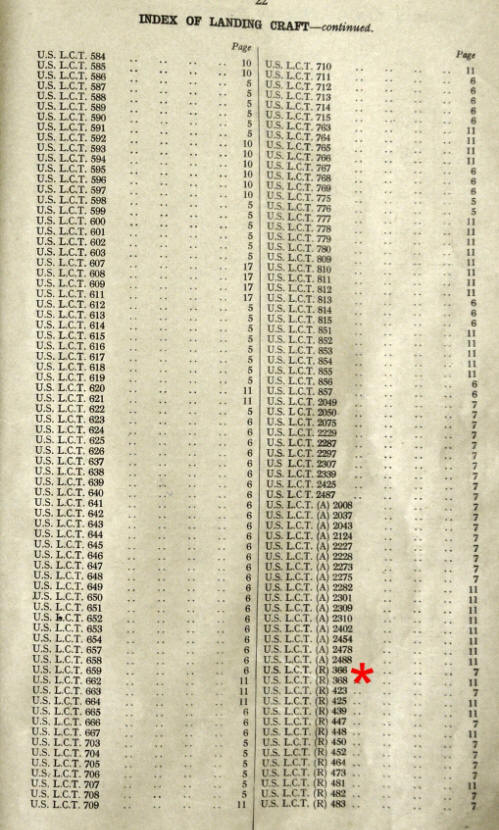

[Photo; Crew of LCT (R) 439. Officers 2nd

row right George Fortune with left arm on hip and Elmer Mahlin].

The best was an ice

cream maker that we later used to great effect in the heat of North Africa

at Bizerte! We let other rocket craft use our freezer if they gave us some

ice cream in return. It was in use constantly! I still have a table cloth

that was given to me by a US tanker crew in Scotland."

While waiting for

the delivery of 12 new LCT (R)s, George remembers, "with Elmer's (my

captain's) permission and the cooperation of the rest of the captains, I

organized a training program for the deck crews of all 12 ships. Subjects

included ship and line handling procedures for leaving and entering port,

docking, the Command structure, daily watches, helmsman duties, signals

and general seamanship. The specialized nature of the work of the Engine

room personnel, excluded them from the training. All available officers

helped with the training, which was undertaken in a positive atmosphere

and good spirits. The general consensus was that all had greatly

benefited from the training."

Preparations for D-Day

The waiting was over

when, in March of 1944, the skipper, Elmer Mahlin, George and the crew,

picked up British rocket ship LCT (R) 439 at Troon on the River Clyde

estuary. Although not known at the time by officers and crew, there were

only around 10 weeks to prepare the craft and crew for the D-Day landings

on June 6th, 1944. The 500 mile journey to the south coast of England

provided an excellent opportunity to break in the new 18 man crew. No

problems were experienced with the craft.

As they prepared for the task ahead, George

recalled, "by spring of 1944,

we were berthed about a mile up the

River Dart with the commanding officer's quarters and offices in the home

of Agatha Christie above us. One day after manoeuvers and practicing at

low tide, we went aground near the sand bar Tennyson referred to in his

poem “Crossing

the Bar” (from Southampton to the Isle of Wight). In the process we

damaged the craft's screws. Replacements were arranged through our

base and fitted by our men."

George also attended the Radar

School at Hayling Island in southern England for a week's training in the

British blind bombing techniques. He stayed overnight in London,

where he twice experienced the German bombing of the city known as the

Blitz.

Not all the

preparations for the invasion passed without incident as George explains,

"We hit a Personnel Carrier (PC) in the fog on our way back to the River

Dart after taking a full load of rockets aboard from stores in Portsmouth.

The PC had the

watch, leading our convoy of about 10 or 12 small craft. We were last in

line and out of nowhere his craft loomed out of the fog heading straight

for us! A collision was unavoidable.

Its commanding

officer was relatively inexperienced but, in

mitigation, it was a dark and foggy day. But for the accident, his vessel

would have marked the 4000 yard buoy off Utah beach on D Day.

Because the fog was

very thick, one of our crew was manning the sound powered telephone on the

bow to give us some extra warning of approaching craft. On sight of the

PC, he instinctively jumped down an open hatch and broke his leg. I

hollered at him to 'get the hell out of there!' just before we hit. I

still remember the crew trying to get the life rafts into the water,

because they thought we were sinking. The skipper and I hollered at them

to get back to their stations. Our bow, being horizontal, cut through the

PC's bow like knife through soft butter. We came to a halt at the position

of their 3" 50 caliber gun, having cut through their chain locker on the

way.

Our bow door broke loose and hung down. Two or three of our

crew dived into the water to run a line through the eye bolt at the end of

the door to crank it up! However, it proved to be too cold to work

effectively, so we proceeded slowly back to

Dartmouth for repairs. My radar training at Hayling Island certainly

helped to bring us safely back to the River Dart in near zero visibility.

The fog might have been a blessing,

because it protected us from U boat patrols! When we arrived in the

Dart, a Free French tug met us. Despite the comedy of them yelling to us

in French and us yelling back in English, we made it through. Good old

Elmer Mahlin, our skipper, had brought us safely to anchor... he got us

everywhere we were supposed to go and we did our job!

All our

preparations for D-Day assumed that it would take place on June 5th but it

was postponed at the last minute because of bad weather. Most vessels had

already set sail for Normandy when the recall order was given. We were

finally able to tie up to a buoy somewhere off southern England. Boy, it

was a nightmare trying to follow the ship ahead since the helmsman was not

able to see over the tall blast shield in front of him. It was up to the

officer on the con to tell the helmsman what course to follow."

D-Day

6th June 1944

%20439%20JULY%2044%20EN%20ROUTE%20TO%20NORMANDY.jpg) About

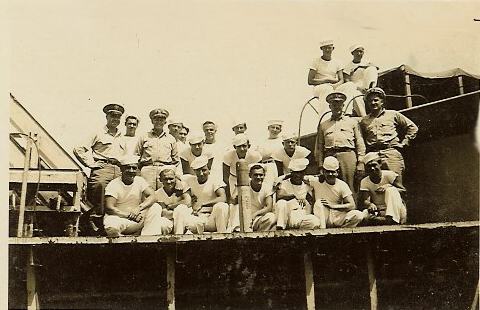

D-Day George wrote to his family, "On D-Day I watched planes fall from the

sky like exploding fireworks, ships around me turning turtle, blown up by

torpedoes and wave after wave of Allied planes flying over and bombing the

Utah beach landing area." About

D-Day George wrote to his family, "On D-Day I watched planes fall from the

sky like exploding fireworks, ships around me turning turtle, blown up by

torpedoes and wave after wave of Allied planes flying over and bombing the

Utah beach landing area."

[Photo; 439 en route to Normandy from

Southern England in July, 1944].

As executive

officer, George pulled the firing switches on 439's first salvo of 1448

rockets. It took about 3 minutes to complete the firing sequence. They

roared over the heads of the initial assault troops in the Landing Craft

Assault (LCAs) en route to the beaches. Timing and accuracy were paramount

to achieve the maximum impact on German morale and preparedness, just when

the Allied troops were about to arrived on the beaches.

"Whilst our firing

was on time and on target, there was some drama on board 439. The skipper,

trying to take refuge in a hut provided to protect him from the heat of

the rocket flames as they ignited, caught his bulky anti-gas outfit and

life jacket on the door,

which exposed his back to the searing heat. Whilst his bulky safety gear

caused the problem, it also saved him from severe burns. The crew wore

their anti-gas outfits and life jackets for a week, without taking them

off!

After the initial

salvo, 439 reloaded and remained in the area of the beaches for 7 days,

ready for further action if called upon. During this time, enemy planes

were active in the area at dusk but the anti-aircraft gunners were too

much for them... they even fired at Allied planes,

because they were so on edge!"

The

Western Mediterranean

"After the Normandy

invasion in June of 1944 our next assignment took our, then, 9 rocket ship

flotilla on a 1,500 mile journey through the Straits of Gibraltar to

Bizerte in Tunisia, North Africa, where we stayed for 2 or 3 weeks. In

July, we headed north in support of Operation Torch, the invasion of

Southern France, stopping off in Naples for fuel and provisions. The

entrance to the harbor was full of ships which had been scuttled by the

Germans to keep the Allies from using them and the harbor facilities.

On

taking up position in the waters off Southern France, between Marseilles

and Monte Carlo, a wing of American heavy bombers passed overhead on their

way to the initial bombardment. We watched in horror as one opened up his

bomb bay doors and let go a whole string of bombs. Boy, were we praying

that they would miss us... and they did. PHEW ! On

taking up position in the waters off Southern France, between Marseilles

and Monte Carlo, a wing of American heavy bombers passed overhead on their

way to the initial bombardment. We watched in horror as one opened up his

bomb bay doors and let go a whole string of bombs. Boy, were we praying

that they would miss us... and they did. PHEW !

At the time, our 9

LCT (R)s were lined up in a row parallel to the beach, ready to fire

salvos of rockets onto the beach barricades. The US Navy sent in a small

fleet of radio controlled LCV (P)s loaded with explosives to blow up the

enemy underwater defensive obstacles, such as hedgehogs. These were

designed to prevent landing craft from reaching the beaches to discharge

their human cargos of fighting men. Unfortunately, the Germans intercepted

the controlling signals, turned the LCV (P)s around and headed them back

towards our destroyers and cruisers. Our big ships could not depress their

guns low enough to sink the craft, so some PCs came in and blew up the

'hijacked' LCV P)s.

We were ordered to

steer east, parallel to the coast, until we could reach an alternative

landing area. At this time we suffered our only casualty in battle. Syers

was a motormac and was under strict orders to stay below deck until the

all clear was sounded. He was writing to his folks and no doubt felt

compelled to go up on deck to see what was happening. The Germans started

firing their dreaded 88s and bracketed us twice with the exploding shells

throwing water spouts up on our deck. Elmer was on the con and I was

checking the crews, radar, and signalmen. Someone hollered 'Man Down!' As

medical officer, I examined Syers but I was sure he was dead. We took him

to a nearby hospital ship, which was with the invasion fleet and said a

prayer as we transferred him. Although a difficult and unwelcome task,

Elmer wrote a letter to Syers' parents. He was a good skipper, always did

what was right!

After the landings

in southern France, we anchored in the then safe surroundings of Ajaccio

Bay. We swam in the sea there and visited Napoleon's home, Naples and

later the harbor at Bizerte in Tunisia."

Workplace and Home

"US LCT (R) 439 was

our workplace and our home for 4 to 5 months since we lived on board at

all times, even when berthed. The officers slept in bunks above the engine

room and mess room and the crew slept in hammocks forward of the mess

room. A cook served substantial hot, healthy food, similar to what was

available at shore based establishments. We loved our ship and worked

together as a family. Leaving her for the last time was an exciting

experience but tinged with sadness, since it was the start of a process

that would see our "band of brothers" disperse to the four winds.

On October 4th,

1944, all the LCT (R)s were returned to the Royal Navy. They were not, as

expected, sailed back to England but transferred to the British base at

Messina on Sicily. All US Navy personnel were repatriated. Clearly the job

of the Rocket Ships was done.

We returned to New

York in September, 1944, aboard the Army troop ship, General Meigs. We ran

into a terrible storm with over 50 foot waves. Surprisingly, this didn't

bother the sailors, who were too preoccupied gambling and generally having

a good time to notice."

In

October of 1944, George was assigned to Commanding Officers Training at

the Little Creek Amphibious training base near Norfolk, Virginia. In

October of 1944, George was assigned to Commanding Officers Training at

the Little Creek Amphibious training base near Norfolk, Virginia.

|

SKIPPER ELMER H MAHLIN

From the ship's log, military communications and personal letters.

Background Background

My dad, Elmer H Mahlin, was in the

Navy during the war, so I grew up hearing phrases like ‘going to

sea’, 'Normandy Invasion’, ‘topside’ and ‘sonofaseacook’, but

without paying much attention. Sadly, by the time I wanted to, dad

wasn’t around anymore. However, he left me a legacy in the form of

his so called "sea chest" - a

large wooden trunk he purchased in

Scotland, the contents of which allowed me to glean much about his

fascinating wartime service.

The chest contained letters, orders,

logs, maps, photos, weapons, a diary and even the flag that flew on

his ship during the D Day assault on Utah beach. While in Scotland,

in 1991, I retraced his footsteps in places like Helensburgh and

Roseneath, near Glasgow, where he trained for several months before

D-Day.

A further journey of discovery

followed 500 miles to the south in Dartmouth and Devon from where

“Force U” convoys began. Most poignant for me was a stained glass

window in

Salisbury

Cathedral which declared:

“See that ye hold fast the heritage we

leave you, yea, and teach your children, that never in the coming

centuries may their hearts fail or their hands grow weak.”

This is the story of Elmer H Mahlin's

wartime service, which his sea chest safely preserved and protected

for 70 years.

Enlistment & Training

14 Apr 1942.

Your application for appointment in the United States Naval Reserve

has been reviewed and favorable consideration cannot be given to

your request (because) the quota for appointment of Officers of your

attainments and specialized training, has been filled.

[From office of Naval Officer

Procurement, Chicago, to EH Mahlin, Lincoln, Nebraska].

15 Nov 1942. A

recent article in The Wall Street Journal indicated the Navy desired

to train men in certain lines. It will be appreciated if you will

review my application….

[To

Director of Naval Officer Procurement, Chicago].

01 Feb 1943.

It is a pleasure to inform you that your application for appointment

as a commissioned officer in the United States Naval Reserve on this

date, has been submitted to the Navy Department. Washington.

[From Bureau of Naval Personnel, Des

Moines].

16 Feb 1943.

Having been appointed in the United States Naval Reserve, the Bureau

takes pleasure in transmitting herewith your commission.

[From the Chief of Naval Personnel,

Washington].

18 Feb 1943.

You will report to the Commanding Officer, Naval Training School

(Indoctrination), Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, on

March 8, 1943. Upon completion of this duty, you will proceed to

Princeton, New Jersey and report to the Commanding Office, Naval

Training School, Princeton University, for further temporary active

duty.

[From the Chief of Naval Personnel,

Washington].

28 Feb 1943.

Enclosures: Acceptance and Oath of office in original white copy,

pink, and two yellow copies….

[From Lieut.

(jg) EH Mahlin, D-V(S), USNR].

02 Jul 1943.

On or about 7 July, 1943 you will proceed to Miami, Florida and

report to the Commanding Officer, Submarine Chaser Training Center,

for temporary duty under instruction.

[From Navy

Department, Washington].

26 Sep 1943.

Following LTS JG DVS USNR HEREBY DETACHED PROCEED WITHOUT DELAY

REPORT CO PHIBTRABASE CAMP BRADFORD NOB NORFOLK VIR DUTY AND FURTHER

ASSIGNMENT TO AMPHIBIOUS SUPPORT GROUPS.

[From the

Commanding Officer, Submarine Chaser Training Center, Miama].

25 Oct 1943.

Enlisted men listed in Enclosure B will be delivered to the

Receiving Station, First Naval District, Boston, Mass. This entire

detail is for further transfer to Support group Landing Craft

Europe.

[From the Commanding Officer,

Amphibious Training Base, Norfolk].

27 Oct 1943.

On or about 28 October, 1943, you will proceed to Prince’s Neck,

Rhode Island, for special anti- aircraft gunfire instruction.

[From First

Naval District, Boston].

Preparations in UK

25 Dec 1943.

My Dear Son Stuart, Thank you many, many times for your Christmas

card and the three pictures of you. Yes, I’ll come home to you as

soon as I can. First we want to help win the war so that millions of

other little boys and girls won’t have to be without their daddies

for a long time, and we men in the forces hope that when you have as

fine a family as I, you will not be obliged to leave your home to

complete a job we did not finish. May God always bless you and your

mother. With love, from Daddy.

[Letter home

from the UK].

26 Jan 1944.

On 29 January, 1944 you will proceed immediately to Compass School,

Slough, England, where you will report for a course of instruction

pertaining to the “Brown Gyroscopic Compass.”

[From the

Commander, Support Group Eleventh Amphibious Force, U.S. Naval

Forces in Europe, Base Two].

12 Mar 1944.

Upon receipt of these orders, you will proceed immediately to

Ardrossan for temporary duty in connection with LCT (R) firing

trials.

[From

Commander, Gunfire Support Craft, U.S. Naval Forces in Europe, Base

Two].

22 Apr 1944.

Lt. (jg) EH Mahlin, USNR, accepted the ship from Lt. G. Miller, RNVR,

on behalf of the US Navy. The American flag was hoisted and Lt. (jg)

Fortune set the watch.

[Ship’s Log:

US LCT (R) 439].

LCTs (Landing Craft Tank) were large,

flat bottomed, powered barges. They were mainly used for the

transport of tanks, infantry and supplies from friendly shores to

the landing beaches in enemy occupied territory. However, there were

many adaptations for firing guns, rockets, anti aircraft flak and

mortars, all in support of the assault troops. The tank decks of the

LCT(R) were filled with a massive battery of 792 or 1080 5-inch

rockets in rows of six. This formidable array of missiles could be

fired electrically in

quick succession

salvos to saturate a given area of beach. The rocket frames were

fixed, so aiming was done by pointing the vessel at the intended

target from a predetermined fixed distance from the beach.

Navigational accuracy was paramount.

Countdown to D-Day

Starting in the first week of May,

1944, the soldiers and sailors of the Allied Expeditionary Forces

began assembling in southern England. Many of the ships left the

Firth of Clyde and Belfast, down the Irish Sea, past the Isle of

Man, then joined by others from Liverpool, Swansea and Bristol. They

sailed in formations of twenty ships, forty ships, even 100 ships to

sail out into the Atlantic and then past Land’s End, where they

turned east for their designated ports of departure such as

Plymouth, Torquay, Dartmouth, Weymouth, and others.

09 May 1944.

SAILING ORDERS U.S. LCT (R) 439. Being in all respects ready for

war, you are required to proceed with US LCT (R) 473, 482 in company

to Appledore for onward routing to Dartmouth….

[SECRET. From

Office of Flag Officer-in-Charge, Greenock].

10 May 1944.

Left Pier 3 Roseneath per orders, followed by LCT (R)s 482, 473 that

order.

[Ship’s Log].

10 May 1944.

We left Roseneath, Scotland, this am. I had been there since 30 Nov

1943. Wrote home tonight. Will mail at Dartmouth. My family and all

my good friends seem so far off. Gave liberty to crews. Some won’t

come home.

[Personal

diary].

16 May 1944.

In Barnstaple Bay. Took lead position our convey and fell in LCT

convoy aft LCT 628 (British) at 1620 hrs. Headed for Land’s End;

destination Dartmouth per orders from NOIC Appledore.

[Ship’s Log].

17 May 1944.

1826. Coming about to enter Dartmouth Harbor.

[Ship’s Log].

19 May 1944.

This date I acknowledge to have received into my custody 17

Smith-Corona .30 caliber rifles, 3 Thompson Sub-machine guns and 44

magazines, one belt, holster, lanyard and 45 caliber pistol….

[To Staff

Gunnery Officer].

19 May 1944.

Heard I made the May 1 promotion to full Lieutenant. Heard from an

Ensign in Comm. that the next exercise is the real show so that’s in

about ten days I guess. May as well have it over with.

[Personal

diary].

21 May 1944.

Learned we test fire Monday and Tuesday, then go to Plymouth

Wednesday for a full load. No doubt show ready to start.

[Personal

Diary].

23 May 1944. 1625.

All fuses in place. Exercises in firing rockets until 1820, H hour

of last run. 2300. Received sailing orders for Plymouth to take on

rockets.

[Ship's Log].

25 May 1944.

At this writing, 2215, we have 736 HE in hold and nearly 936 in the

racks. Tomorrow we get fuses. 200 smoke and 72 incendiary or ranging

rockets. A hell of a lot of dynamite should anyone ask. It won’t be

long until the business I don’t think. Wonder if I’ll be alive a

week from now, whole and sound. That sort of problem is uppermost in

the minds of all of us.

[Personal

diary].

26 May 1944. 1430.

Ammo all loaded, barges left.

[Ship's Log].

27 May 1944.

2225. River Dart, Dartmouth, England. Tied up to LCT 2024. Engines

secured.

[Ship's

Log].

29 May 1944.

1800. At entrance to Salcombe Harbour.

[Ship's

Log].

03 Jun 1944.

1625. Left Salcombe Harbour under secret orders for “Operations.”

1735. In position as no. 18. US LCT (R) 368 ahead, US LCF 27

astern. 1905. Convoy coming out of Dart River. 1925. Escort

destroyer 723 abeam.

[Ship's Log].

The speed of the convoy was limited to

the top speed of the slowest component – the LCTs laden with their

precious burden of modern fighting equipment and carefully trained

men. The naval workhorses of the Normandy invasion were the landing

craft and the ships just offshore that supported them. Only a

handful of battleships and cruisers were assigned to the Normandy

operation and the battleships that did go were the real antiques.

Aircraft carriers were not needed because airplanes could easily fly

across the Channel from Britain to attack targets in France.

[Stillwell,

Assault on Normandy, Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1994].

04 Jun 1944. 1845. Dropped

anchor Weymouth Bay. LCT 437 ahead, LCT 646 and LCT (R) 368 on port

beam.

[Ship's Log].

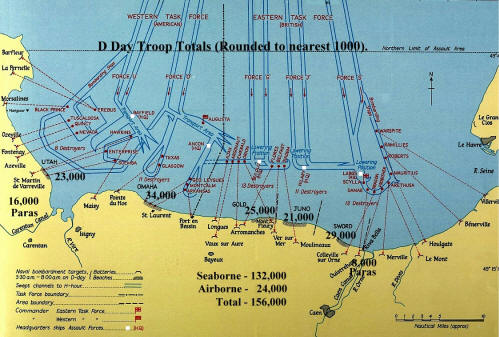

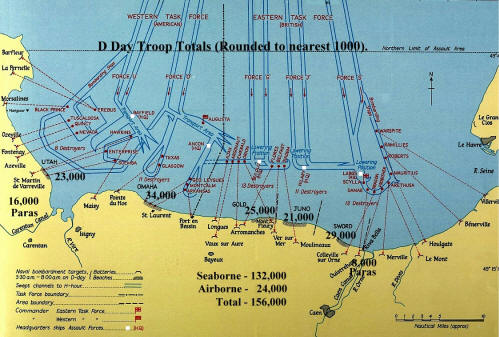

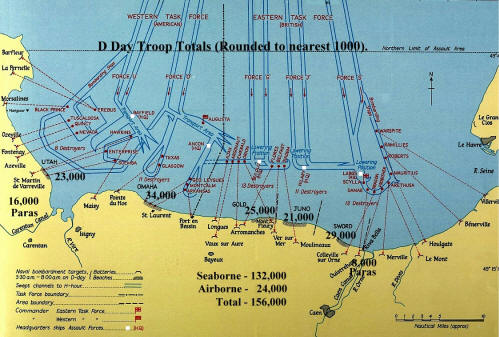

Altogether there were 2,727 ships

ranging from battleships to transports and landing craft that would

cross.

They were divided into the Western

Naval Task Force (931 ships headed for Omaha and Utah) and the

Eastern Naval Task Force (1,796 ships headed for Gold, Juno and

Sword).

On the decks of the LSTs were the

Higgins boats and other craft too small to cross the Channel on

their own. There were 2,606 of them. Thus the total armada amounted

to 5,333 ships and craft of all types.

[Ambrose,

D-Day, June 6, 1944, The Climatic Battle of World War 11, New York,

Simon & Schuster, 1994].

05 Jun 1944.

0200. Pursuant to orders delivered by Lt. Finneran of GFSC, crew

roused, Engines started.

[Ship's Log].

At 0415 land was plainly visible. The

rapidly approaching dawn revealed the thousands of ships and craft.

As far as the eye could see, they stretched toward the English

Channel.

[Stillwell].

D-Day & Aftermath

06 Jun 1944.

This is D-Day. About 0400 we were off our course but followed LCT

(R) 368. We saw some C-47s coming back and what appeared to be

flares. About 0530 arrived at transport area. At 0600 LCI 209

(Landing Craft, Infantry) informed us H hr was 0630 and get the hell

to it.

Ahead was 1st wave small boats. Guns

(Landing Craft, Gun) and flaks (Landing Craft, Flak) crossing our

bow. Stopped, then speeded up, trying to determine position. Unable

to get it as marker vessels not in place. Identified Nevada

firing on our target.

From St. Marcouf islands and radar,

got on our course and started in. Had to stop for second small boat

wave. LCF 31 and a Coast Guard boat went down in the lane where we

would have been had we not been delayed. By the grace of God I

believe we were spared.

(Personal

diary.)

The Naval bombardment of designated

targets began on schedule at 5.50 am and lasted forty minutes. Then,

as soon as our warships stopped shooting, about three hundred B-26

Martin Marauder two-engined medium bombers, swept in to attack. More

than four thousand bombs smothered the German positions. Though the

bombs did not destroy many of these, they did explode many enemy

land mines. So, too, did the rockets from seventeen LCT (R)s that

were specially

equipped

for this bombardment role. The noise was deafening: returning planes

roaring back to Britain to reload and fire-support ships belting

away at unseen targets inland, making an almost continuous wall of

sound.

[Stillwell]. equipped

for this bombardment role. The noise was deafening: returning planes

roaring back to Britain to reload and fire-support ships belting

away at unseen targets inland, making an almost continuous wall of

sound.

[Stillwell].

The 276 B-26 Marauder medium

bombers of the Ninth US Air Force dropped 4,400 bombs on the German

positions, whilst four LCGs (Landing Craft, Gun) armed with 4.7 inch

guns opened fire at short range on the beach defences. Meanwhile,

the cruisers and battleships continued to pound their targets. When

the LCV (P)s (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel) were at 7,000 yards

from the shore, seventeen LCT (R)s began to unleash their salvos of

thousands of rockets in a fearsome display of light and explosions.

This hurricane of fire soon covered the coast in a thick cover of

smoke, which masked the few landmarks visible to the naked eye.

Radar was of little use, either.

[Buffetaut,

D-Day Ships, The Allied Invasion Fleet, June, 1944, London, Conway

Maritime Press, 1994].

06 Jun 1944. 0600.

In transport area. 0637. Fired rockets at 3500 yds. radar from

wall. 0930. Dropped anchor in Red Circle area to begin loading and

fusing rockets. 1125. English LCT, out of commission, loaded with US

troops, drifted into our stern severing our anchor cable.

[Ship's Log].

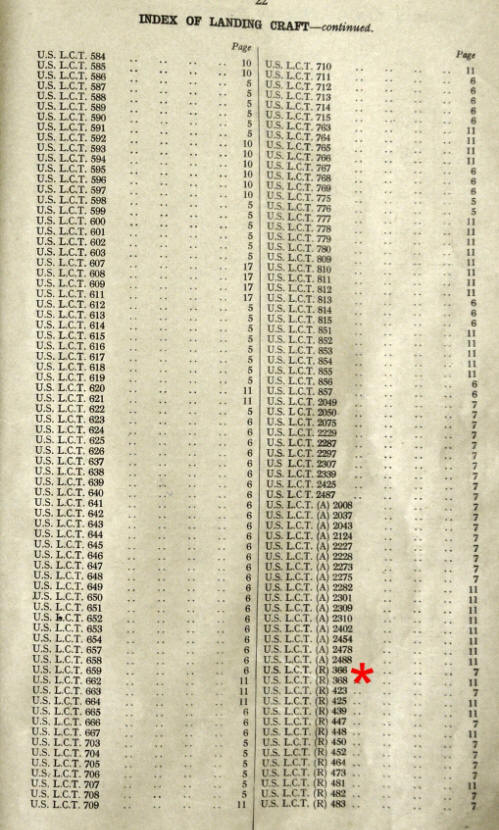

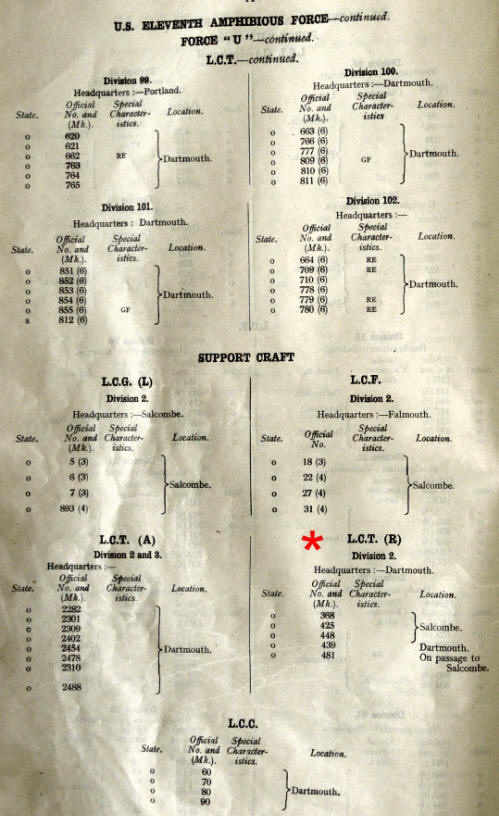

[Opposite; Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' showing the

disposition of US LCT (R) 439 and other support craft].

07 Jun 1944.

0800. Tied bow to bow LCT (R) 368 about 4 miles from invasion coast

of France. 1845. Rocket loading completed. 2045. Moving to new

position.

[Ship's Log].

08 Jun 1944.

Went to sleep – frequently awakened. Ack-ack, gunfire, etc. There is

a tremendous amount of allied Navy and Airforce here and absence of

German counterpart. We expect a raid soon.

[Personal diary].

08 Jun 1944.

0130-0200. Bombs being dropped nearby. Ships sending up flak. 1230.

Ship off port quarter, 2,000 yds. Sunk by mines.

[Ship's Log].

09 Jun 1944. 1030.

Ship on stern sunk by mine. 1430. Bombers overhead. Bombing beach.

Flak falling on deck. 2125. Radio report of enemy planes coming in.

[Ship's Log].

13 Jun 1944. 0520.

Pursuant to orders, let go lines from LCT (R) 368. Standing by

waiting for convoy to form. 0830. Proceeding toward Portland in

fairly heavy sea about 5 knots. 2400. Approaching Weymouth Bay.

Visibility good. Rockets defused.

[Ship's Log].

14 Jun 1944. 1605.

Received new anchor, food supplies and also 2 barrels of SAE 30 oil.

[Ship's Log].

14 Jun 1944.

Dear Stuart, If you were here today, Sonny, I’d take you around the

ship and show you what we have aboard. Perhaps your mother can tell

you what we fire. Anyhow, we’ve been through one invasion and I

guess, when we think it over, it was quite an experience. I do hope

you will be spared this when you grow up. We are in a port now

getting needed supplies. We broke some lines. A ship ran into us and

cut our anchor cable so we were without an anchor. We’ve had a few

bumps and dents here and there but nothing serious. The worst job is

keeping in a convoy in the dark. I hope soon to get the mail that is

piled up for me. Must close now, Son. Write you later. Love, Daddy.

[Letter home

from UK].

15 Jun 1944. 2330.

Moored at Dartmouth.

[Ship's Log].

16 Jun 1944.

Received lots of mail today. How I would like to be home.

[Personal diary].

18 Jun 1944.

We listened to American forces programs – it’s grand. It’s wonderful

just to walk along the streets, look at trees, hills. I feel lucky

to be alive and well, and am thankful for all that.

[Personal

diary].

08 Jul 1944. 0920.

Underway from Dartmouth to Plymouth.

[Ship's Log].

North Africa

12 Jul 1944. 0850.

Left mooring under orders. Destination, Gibraltar.

[Ship's Log].

12 Jul 1944.

En route Gibraltar. Assume may be an operation in S. France. We have

destroyer escort. I liked Dartmouth – nice and homey there.

Yesterday I heard a picture may have been taken of us firing at

Normandy. Hope to get one.

[Personal diary].

20 Jul 1944.

1530. Destination is Oran, Algeria. Fuel on hand 3984 gal. Water

2950 gal. Approximate speed has been 7-1/2 knots. Fuel consumption

20 gallons per hour.

[Ship's

Log].

28 Jul 1944.

2307. Dropped anchor in Bizerte.

[Ship's Log].

28 Jul 1944.

It seems strange not to be in British Isles. I must get home soon.

In a few days I’ll have been away for 9 months – it’s too long. If I

never see any more LCT (R)s I’ll never miss them.

[Personal

diary].

03 Aug 1944.

0400. Gyro started. Prep departure for Naples.

[Ship's Log].

06 August 1944.

1320. Moored to B645 Naples Harbor.

[Ship's

Log].

07 Aug 1944.

1100. Began loading rockets.

[Ship's

Log].

09

Aug 1944. We got underway

about 1030 and at 1300 were in formation. Bound for Corsica and

finally Frejus, France, for an attack. We will come in near St.

Rafael.

[Personal

diary]. 09

Aug 1944. We got underway

about 1030 and at 1300 were in formation. Bound for Corsica and

finally Frejus, France, for an attack. We will come in near St.

Rafael.

[Personal

diary].

Big transports sailed from Naples.

Smaller landing craft had to be sent earlier from various other

places, some of them from Corsica. For this operation we had a

considerable Naval force. We had three of our battleships, several

cruisers, and a large number of destroyers and minesweepers, as well

as the transports and landing craft.

[Stillwell,

Assault on Normandy, Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1994].

12 Aug 1944.

0021. Approaching Ajaccio Bay, Corsica.

[Ship's Log].

13 Aug 1944. 1855.

Underway to take position in convoy for assault near Frejus and St.

Raphael.

[Ship's Log].

14 Aug 1944.

1630. Five waves Liberators flew over. 2103. Explosions heard from

assault area.

[Ship's Log].

[Opposite; In this index page from the

Admiralty's "Green List" the prefix US is used for the LCT (R)s

whereas on the disposition pages above no prefix is used. This is

most likely because the "US Eleventh Amphibious Force" heading

renders the US designation against individual craft superfluous].

15 Aug 1944. 0400.

Arrived transport area. 0605. Shells flying stbd. 1410 Rocket

stations ordered. 1420. Ordered to turn about and proceed to

transport area. Enemy gunfire on starboard beam. 1430. Syers F 1/c

was hit in chest with shrapnel from shell in port quarter. 1622.

Small boat from PA28 took body ashore to Green Beach for burial.

[Ship's Log].

15 Aug 1944.

I lost a man today.

[Personal

diary].

16 Aug 1944.

1625. In convoy for Ajaccio.

[Ship's Log].

02 Sep 1944.

1410. Passed into Bizerte, Coulet du Lac. Convoy formed in column.

1500. Moored portside to pier 27.

[Ship's Log].

25 Sep 1944.

1530. All officers except CO moved off. Orders are for CO and eight

of crew to take craft to Messina, Sicily.

[Ship's

Log].

Back to the USA

26 Sep 1944.

You will proceed immediately and report to the Commanding Officer

Eighth Amphibious Force for transportation to the United States.

[From

Commander United States Eighth Fleet].

01 Oct 1944. 0800.

Colors. Message from Admiralty to de-store loose permanent store

articles. 1000. Gave to LCI 563, 2 Army telephones, ice cream

freezer, 3 battle lanterns, excess foul weather gear, tools, dishes,

canvas, and food.

[Final entry

in Ship’s Log].

31 Oct 1944.

Upon Expiration leave report Amphibious Training Base Camp Bradford

Naval Operating Base Norfolk for temporary duty connection

amphibious operations and for further assignment to such LST

(Landing Ship Tank) as Commander Amphibious Training Command

Atlantic Fleet may designate. [Western

Union Telegram].

02 Mar 1945.

You will proceed immediately and report to the Commanding Officer,

Navy Pier, Chicago and for further transfer to the Supervisor of

Shipbuilding, Seneca, Illinois for duty in connection with the

fitting out of the US LST 1134 and duty on board.

[From

Amphibious Training Base, Norfolk].

18 Apr 1945.

The arrival inspection for US LST 1134 was held by LST Shakedown

Group, St. Andrew Bay, Panama City, Florida.

11 Jun 1945.

You will proceed and report to the Commanding Officer, Amphibious

Training Base, Oceanside, California for duty as Platoon Officer in

connection with Beach Battalion A and duty outside the continental

limits of the United States. Issued transportation on these orders

from Norfolk to Oceanside via Chesapeake & Ohio (Cincinnati), New

York Central (Chicago), Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (Denver),

Denver & Rio Grande (Ogden), Union Pacific (Los Angeles), Atchison,

Topeka & Santa Fe (destination). [From

Amphibious Training Base, Norfolk].

Dad was in the Philippines when, on 6

August 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on

Hiroshima. He was to have been in the initial assault force in the

planned invasion of the Japanese mainland.

12 Nov 1945.

From Office of the Commander , Amphibious Forces, U.S. Pacific

Fleet. Subject: Release from active duty. |

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around

300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search

banner checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in

or copy and paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for

book suggestions. There's no obligation to buy, no registration anmahlin,d

no passwords. Click

'Books' for more

information.

1) On this

CombinedOps website read

US NAVY LANDING CRAFT TANK

(ROCKET)

by Lt Commander Carr. His account of 14 LCT (R)s includes 439 and

concentrates on US Landing Craft Tank (Rocket) training in the USA and the

UK and operations in Normandy and Southern France in the summer of 1944.

2) Specification of

LCT (R) 439 at

NavSource

Website.

3)

The National D-Day Museum

in New Orleans, USA holds the logs and records of LCT (R) 439 donated by

Stu Mahlin of Cincinnati, Ohio, whose father, Elmer Mahlin, commanded LCT

(R) 439. Mahlin fired his rockets off Utah Beach on D-Day at 0635, just in

advance of the initial assault troops.

The craft was

decommissioned off Sicily on 1 October, 1944. Mahlin took all its

paperwork with him, including every order he received during the war. This

valuable material included the original log of LCT (R) 439, the US log

starting 22 April 1944, which was the date Mahlin accepted the craft from

its British commander. Other material includes his diary, orders, sea

charts, snapshots, sea chest and even the American flag that flew from

LCT(R) 439 on D-Day.

Also included in the

collection are Mahlin's sidearm and records pertaining to his service as

Commanding Officer of the Naval Reserve Training Center in Lincoln,

Nebraska. It is one of the most complete records of one sailor's service

during World War II.

Correspondence

Good day to

you! I came across your website which brought back many memories of my

father's wartime service.

He

initially tried to join the Marines because my mom was German, and he

wanted to fight in the Japanese in the Pacific. His childhood, lifelong

friend and best man at his wedding, Buddy Campbell, also applied to join

the Marines, which he did successfully. However, my father was told the

Marines were full, and that he was now in the US Navy. Buddy survived WW

2, but late recruits from 43 and 44 were called back for duty in Korea.

He was amongst the first troops to fight in Korea and, sadly, he died on

a 'Korea Death March.'

My dad was in

charge of a US LCT (Landing Craft Tank) on D day at Omaha Beach. His

name is Charles J. Payne with the rank of Chief Boatswain's Mate, First

Class. He signed up in May 1943, after working at the Brooklyn Navy

Yard, and was assigned to a US Navy training station in Sampson, New

York State on the Great Lakes, for immediate landing craft training, and

just prior to going to the UK, he attended Fort Pierce, Florida for

advanced training in landing craft operations.

Prior to D Day, he

was stationed in Plymouth on the south coast of England. On D Day

itself, his LCT was being towed from England when the tow cable broke.

He arrived on Omaha beach much later in the day than planned. On D Day

+1, his craft's responsibility was to pick up dead floating soldiers

along a length of the landing beach. After the landing phase, my dad,

like many other US Navy staff from the landing, was assigned to the army

as cooks and support staff. Once the front advanced close to the German

border near Bremen, he was further assigned river boat duty. He survived

the war and I ate army food growing up!

Thanks for the

site. As I said, it brought back a lot of memories, one of which

concerned training in Southampton and Bournemouth. The Navy staff

customarily frequented the local pubs, but they were very unhappy that

there was no ice and all beer was warm. The locals used to challenge

them to games of darts and always won. However, after a few weeks, the

pubs provided ice and cold beer was readily available. The pubs became

very popular and the yanks, after learning darts, became so good at it,

the locals refused to challenge them!

Acknowledgements

The information for

the first part of this page, was provided by George F Fortune who served

as Ensign on US LCT (R) 439. The information was edited for presentation

on this website by Geoff Slee and approved by the author before

publication. We're also grateful to Stu Mahlin, son of skipper Elmer

Mahlin, for sharing his father's wartime experiences in the second part of

this page. The information was taken from a variety of sources including

the ship's log, official r ecords

and personal correspondence. Maps, Imperial War Museum photographs and

extracts from the Admiralty's "Green List" of landing Craft dispositions

were added later for illustrative purposes. ecords

and personal correspondence. Maps, Imperial War Museum photographs and

extracts from the Admiralty's "Green List" of landing Craft dispositions

were added later for illustrative purposes.

|

_small1.jpg)

%20439%20ensign.jpg)

Roseneath

Castle was quite isolated, so the ship's crews mostly stayed on the base.

Officers were permitted to venture outside the base for the purposes of

sightseeing. However, it was not always the case as George recalls;

"together, with a couple of crew members, we took small boat trips from

our base at Roseneath Castle to call on our big ships anchored in the

area. We bummed anything that we could beg, borrow or beg louder for.

Roseneath

Castle was quite isolated, so the ship's crews mostly stayed on the base.

Officers were permitted to venture outside the base for the purposes of

sightseeing. However, it was not always the case as George recalls;

"together, with a couple of crew members, we took small boat trips from

our base at Roseneath Castle to call on our big ships anchored in the

area. We bummed anything that we could beg, borrow or beg louder for.

%20439%20JULY%2044%20EN%20ROUTE%20TO%20NORMANDY.jpg) About

D-Day George wrote to his family, "On D-Day I watched planes fall from the

sky like exploding fireworks, ships around me turning turtle, blown up by

torpedoes and wave after wave of Allied planes flying over and bombing the

Utah beach landing area."

About

D-Day George wrote to his family, "On D-Day I watched planes fall from the

sky like exploding fireworks, ships around me turning turtle, blown up by

torpedoes and wave after wave of Allied planes flying over and bombing the

Utah beach landing area."