|

US Landing Craft Infantry (Large) 502; D Day.

US LCI (L) 502, carried 196 Officers and men of the Durham Light Infantry to

Gold Beach on the morning of June 6th,1944. This account is based

on the writings and recollections of John P Cummer and information from the

craft's Deck Log.

D-Day Draws Near D-Day Draws Near

On Saturday the 3rd of June, 1944, our ship, the United States

Landing Craft Infantry (Large) 502 or US LCI (L) 502 for short, docked at

the Royal Pier, Southampton, England where we embarked 196 officers and men of

the Durham Light Infantry, 151st Brigade, 50th

Northumbrian Division, British 8th Army. They were carrying freshly

printed French currency, a strong indication that this trip was for real.

As they clambered aboard carrying folded

bicycles with various bits of kit and equipment about them, they looked more like

peddlers than soldiers. They were, however, first class troops and were to prove

themselves so in the fighting that lay ahead.

Fully loaded

to the limit, we returned to our usual berth at New Docks along with the other LCIs of Group 31. On Sunday, June 4th,

the crew's final preparations for the coming operation began. A church

party went ashore and returned and the troops were permitted ashore for

some much needed exercise and relief from the crowded conditions. The routine general quarters were sounded for an air raid alert

at 2030. We stood to our guns for twenty minutes or so, before securing.

Our group was, thankfully, not involved in the abortive foray on June 5th,

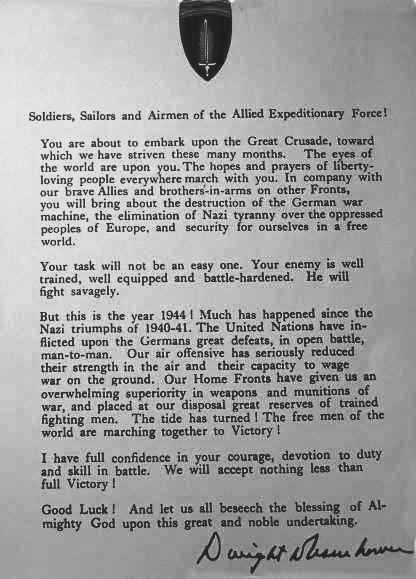

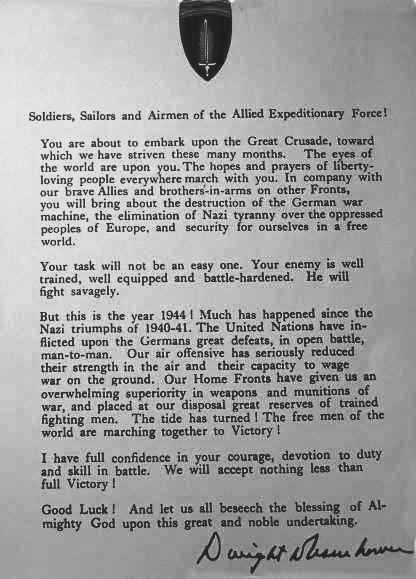

which was recalled because of bad weather. However, when a message to the Allied

Expeditionary Force from General Eisehower was read out to the ships company at

1400, we knew we would soon be sailing for the "far shore".

Throughout that day, more and more ships slipped out of the

once crowded harbor until it seemed that we were the only ones left. It was an

eerie sensation. Finally, at 2000 on June 5th, our group began slipping lines to

manoeuvre out into the channel. We cast off at 2012 taking our place in column,

behind US LCI (L) 512. Our escort ship, HMS Albrighton, joined us us as we passed

the Needles

Light on the eastern tip of the Isle of Wight. We formed into divisions for

the assault and were on our way.

The

Crossing

Jolly Miller and I shared the bow watch from 2000 to midnight that night. As

usual, he was ebullient and talkative, excited about what was coming. "Just think, JP," he said to me, "by this time tomorrow, we’ll be veterans!" I shared some of his anticipatory excitement, but,

when we were relieved at midnight, I felt the need to be alone. Imminent danger has a way of awakening spiritual concerns.

Godly parents had raised me to take the Christian faith seriously. On this night

before battle, I felt the need for reminding myself of the certainties and

comforts of that faith.

Finding a place to be alone on a 153 foot landing craft,

crowded with 196 troops, could have been a problem but I had my own private

place, cramped though it was. Under the fantail deck was a small magazine where

ammunition was stored. As the Gunner’s Mate, I had the key to my own 'quiet time'

place.

I sat on the cold, steel deck, surrounded by the cases of

ammunition and read from the New Testament that had been given to me by the

Gideons. The guide to references inside the front cover had suggestions for

special times. One was "for times of peril or danger", and it directed me to

Psalm 91: I sat on the cold, steel deck, surrounded by the cases of

ammunition and read from the New Testament that had been given to me by the

Gideons. The guide to references inside the front cover had suggestions for

special times. One was "for times of peril or danger", and it directed me to

Psalm 91:

[Photo; the author, John P Cummer].

"He that dwelleth in the secret place of the Most High

shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the LORD, He is

my refuge and my fortress: my God, in Him will I trust. Surely he shall

deliver thee from the snare of the fowler and from the noisome pestilence.

He shall cover thee with his feathers, and under his wings shalt thou trust.

Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that

flieth by day; nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the

destruction that wasteth at noonday. A thousand shall fall at thy side, and

ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee . . . "

". . . but it shall not come nigh thee . . ."

A deep sense, not of fearless bravado, but of assurance in

the protection of a sovereign God, came to me as I read those verses. To this

day, every time I re-read them, that tiny steel cubicle surrounded by cases of

ammunition, pitching with the motion of the sea, comes immediately to mind. In

God’s providence, that protection was afforded to me and my shipmates on D-Day,

June 6, 1944.

In the early hours of June 6th, as we entered the

swept channels through the minefields north of Seine Bay, hoping that the

%20502%20DISPOSITION%20heading_small.jpg) minesweepers had done their job, the nine LCIs of Group 31 formed up for the

assault, as directed in Group Commander Patrick’s order. We were in three

columns, the first led by 501 with 507 and 509 in her trail. In the center column, Commander Patrick rode in

512, his flagship, with the 500 and the 499 astern. In the right hand column, 506 led with our 502 and the 508

following. minesweepers had done their job, the nine LCIs of Group 31 formed up for the

assault, as directed in Group Commander Patrick’s order. We were in three

columns, the first led by 501 with 507 and 509 in her trail. In the center column, Commander Patrick rode in

512, his flagship, with the 500 and the 499 astern. In the right hand column, 506 led with our 502 and the 508

following.

%20502%20DISPOSITION_small.jpg) As the sun rose that morning, we could see the vast

armada around us and the canopy of allied aircraft overhead with

their distinctive D-Day markings of black and white stripes painted on wings and

fuselage. Someone, later describing this scene, said that it looked like you

could walk across the English Channel on the wings of the aircraft. In the distance,

we could see the smoke rising from the beach. The

noise of the naval bombardment was continuous. As the sun rose that morning, we could see the vast

armada around us and the canopy of allied aircraft overhead with

their distinctive D-Day markings of black and white stripes painted on wings and

fuselage. Someone, later describing this scene, said that it looked like you

could walk across the English Channel on the wings of the aircraft. In the distance,

we could see the smoke rising from the beach. The

noise of the naval bombardment was continuous.

[Disposition of 502 and her sister craft as

they appeared in the Admiralty's 'Green List' just prior to D-Day].

The

Landing

At 0755, our escort vessel, HMS Albrighton,

used her

blinker signal light to advise that the landings were going according to plan. We

sighted the coast of France at 0855 and began circling in the ingoing area,

waiting for the signal for our group to proceed to the beach. Shortly after 0900,

Commander Patrick signalled the group to prepare to beach. The last movement was

underway.

My battle station was at the number one gun atop the focs’l,

thus placing me in the farthest point forward aboard our ship, a genuine

ring-side seat with the drawback of being an excellent and highly

visible target. With our gun cocked and loaded. we talked, watched and waited,

speculating as to what was going on ashore, when we would head in and how much

opposition we would face.

In the log book, Engineering Officer, Mr Krenicky, made the entries for that memorable day. He noted that they observed a German tank

hit on a hillside and, as we shifted to beaching stations at 1030, a German

75mm gun was still in operation as well as mortar fire. At 1040 he wrote: "Standing in to Jig Green sector of Gold Beach, Asnelles-Sur-Mer, Arromanches sector."

The noise, smoke and confusion grew as we threaded our way through a mass of

wrecked landing craft, tanks and beach obstacles. The ordered, tight directions of

our Group Commander gave way as the utter confusion of

the beach made it totally impossible. It was every ship for itself. I was told, years later, by a crew member of the 508, that their Captain had his

eye on the same landing spot we were heading for and cursed our Skipper roundly

as we beat him to it! The noise, smoke and confusion grew as we threaded our way through a mass of

wrecked landing craft, tanks and beach obstacles. The ordered, tight directions of

our Group Commander gave way as the utter confusion of

the beach made it totally impossible. It was every ship for itself. I was told, years later, by a crew member of the 508, that their Captain had his

eye on the same landing spot we were heading for and cursed our Skipper roundly

as we beat him to it!

Our landing resembled none of the multitude of practice

landings we had made. We scraped over some submerged object for the length of

the ship but suffered no damage. At one point, close to the shore, our bow was aimed directly

at a sunken truck (photo opposite) with two wet, forlorn-looking soldiers clinging to it. At the

last moment, we changed course to avoid them. With a look of great relief on

their faces, they waved to us as we lurched past them on our way to the rather

improbable landing spot our Skipper had chosen out of necessity - a broached

British LCT.

HM LCT 857 was stranded parallel to the beach. She had taken

a good pounding and was in no shape or position to disengage herself from the

beach. Our Skipper considered 857 was the best place for

disembarking our troops, so he ran our bow right up on to the broached LCT.

The ramps were extended, lowered onto the LCT at somewhat

perilous angles and our bicycle-toting Tommies struggled down our ramps,

clambered over the LCT and finally dropped off onto the beach itself.

While our troops were disembarking, we became involved in two

rescue missions. With no threat from German aircraft and being much too small to

consider challenging German 88s, we secured our gun and became involved in those rescue missions While our troops were disembarking, we became involved in two

rescue missions. With no threat from German aircraft and being much too small to

consider challenging German 88s, we secured our gun and became involved in those rescue missions

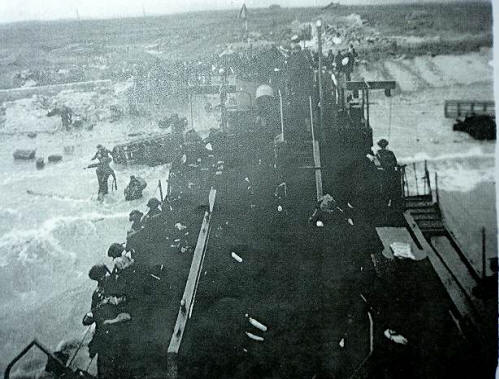

[Photo opposite; Gold Beach on D-Day: LCI (L) 502 with her bow up against

HM LCT 857 a Mk4 LCT of the 33rd LCT Flotilla of D LCT Squadron. The flotilla

delivered Royal Artillery on the morning of D-Day on to Gold beach].

First, the skipper of the British LCT, on whom we had

descended uninvited, asked if we could give him a tow as we retracted. Bos’n

Walt Sellers and some of the deck gang rigged a cable and passed it to the LCT,

the plan being to try to "unbroach" the craft as we retracted.

Then some British sailors, stranded on the beach after losing

their small boats in the first wave, asked if we could take them off the beach.

We passed another line down to them, which they secured on the

broached LCT and began climbing hand over hand up to our focs’l. We hung,

somewhat precariously over the bow, leaning down to grab and haul them

aboard. We had rescued 27 of them when the Skipper decided it was time

to retract.

Return

to England

At 1141, Bos’n Sellers was ordered to cast off the line to the

LCT and the Skipper began backing our LCI off the beach. The line that the small

boat survivors were using snapped taut; one sailor fought for dear life to hang

on. We were able to reach down and grab him before the line parted.

With the perspective of a sailor on

the bow, instead of an officer in the Conning Tower, I was livid.

I was sure we could have rescued more of the British sailors and

spared them continued exposure to

gunfire on the beach. I was equally sure that we could have done more to help

the broached LCT get off the beach. The issue, I was told later, was that time

was running out before the tide began to turn. With the perspective of a sailor on

the bow, instead of an officer in the Conning Tower, I was livid.

I was sure we could have rescued more of the British sailors and

spared them continued exposure to

gunfire on the beach. I was equally sure that we could have done more to help

the broached LCT get off the beach. The issue, I was told later, was that time

was running out before the tide began to turn.

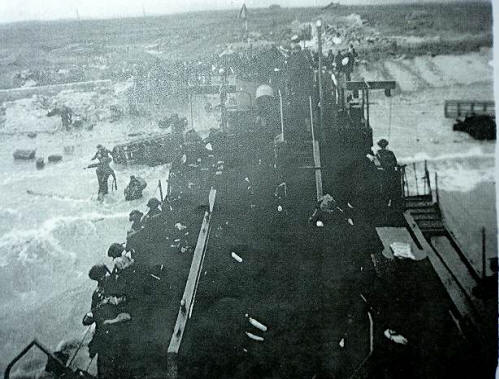

[Photo opposite; On Gold

Beach. Taken from conning tower of 508, which was next to 502].

Was the Skipper right in pulling out when he did? Probably.

Other crew members grumbled angrily about it, as I did but, in retrospect,

there is no reason to question his decision. The "what if . . ." game is one of

the most futile of all enterprises. After successfully retracting, we threaded our way back

through the wreckage that littered Gold Beach. Our part in the D-Day assault was

over. We had successfully landed our troops and rescued some stranded sailors. The work of supporting

the troops already landed, by ferrying 'build up' troops across the channel, was about to begin.

We stayed at action stations for the rest of D-Day. Around us

the gun support ships were firing almost continuously. HMS Belfast, now

on permanent display in London on the Thames, just opposite the Tower of London,

was one of the ships closest to us. We could not see clearly what was happening

ashore. There were ceaseless explosions on the beach and a pall of gun smoke

hung over everything. Overhead, wave after wave of aircraft, fortunately bearing

the black and white D-Day striping of the invasion forces, came on steadily.

Around 1600, we were formed up with other LCIs

for our return trip to England. The ever present danger of German E-Boats

dashing out for raids, ensured we

strained our eyes to see in the darkness. Nothing happened but the long

tension-packed day and anxious watch left me, and I am sure other crew members,

completely exhausted.

At 2315, the lights of the Isle of Wight came into view. We

were safely back from the "far shore".

Troops in Southampton

prior to D-Day awaiting departure.

LCI 502, first left, awaits the order to sail for

France. Southampton Docks.

Conn of 502 from

adjacent LCI Southampton docks.

US LCIs underway

across the channel on the evening of June 5 1944.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Correspondence

I read with

interest the account by John P Cummer of the arrival and exploits of LCI

(L) 502 on Gold Beach, D Day June 6th 1944.

I was

recently contacted by the son of the Captain of LCT 857 (the LCT that

502 tried to tow off the beach). He had found in his fathers papers

that LCT 857 transported my father and 4 Sextons of E Troop, 465

Battery, 90th field regiment Royal Artillery who landed at 0825hrs on

June 6th 1944.

We plan to

be on the exact spot on Gold Beach at 0825 hrs on June 6th 2024 to

commemorate their extraordinary feats 80 years on. If any relatives of

veterans who served on either craft that fateful day intend to

commemorate the event as we do, we'd love to hear from you using the

email link opposite.

Kind

regards

Chris Wood

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to John Cummer for this account

of US LCI (L) 502

on D-Day including photographs and to Tony Chapman, archivist and

historian for the LST and Landing Craft Association for his assistance.

|

D-Day Draws Near

D-Day Draws Near

%20502%20DISPOSITION%20heading_small.jpg)

%20502%20DISPOSITION_small.jpg)