|

519 Landing Craft Assault Flotilla - 519 LCA Flotilla.

6 Troop Carrying LCAs, then 5, then

4.

Background Background

Leonard Albert King was just 20 years old

when he piloted

his flat bottomed Landing Craft Assault

(LCA)

to

the Normandy beaches,

early on D-Day morning.

Although he

was amongst the first to land on the heavily defended beaches,

his account belies the extremely hazardous position of his craft. This account

is based upon

the diary he maintained

for several weeks around this time.

[Photo;

Assault landing craft leaving an infantry carrying craft (mother ship) as they

prepare to make their way to the landing beaches. © IWM (A 23113).

Barry Miller confirms that the craft was LCA 721 of the 521 Assault Flotilla

from the Ulster Monarch, hence the “UM” sign].

LCAs were not designed to travel long

distances in open seas.

Accordingly, they were

usually

carried to the landing beaches on mother

ships, not unlike modern lifeboats, suspended from davits. Len's mother ship was the

SS Princess Maud,

which, pre war, had been a railway

ferry

that plied the waters between Stranraer,

in south west Scotland,

and

Larne in Northern Ireland.

She had been requisitioned for war service and

converted to a troop carrier with additional capacity to carry 6 LCAs, each

with a

capacity

about 35fully armed troops.

These early

designed

LCAs were constructed of

wood,

with some armour plating for protection against rifle and machine gun fire.

They were powered by two Ford V8 engines

driving twin screws

to produce a

cruising speed of 7 knots.

Her crew of four

comprised a coxswain, mechanic, gunner and sheets man (?).

D-Day D-Day

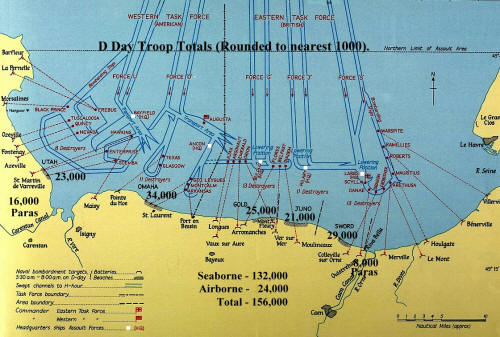

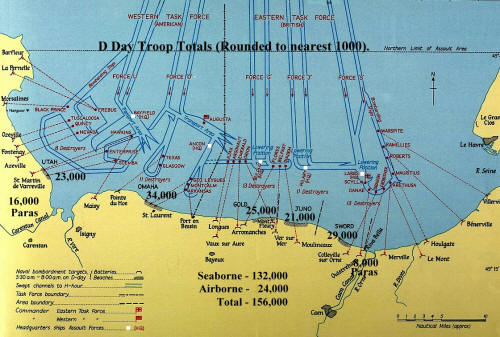

On the night of 5 June,

1944, after a delay of 24 hours

due to bad weather, we set off for Omaha beach near the town of Vierville

as part of 519 LCA Flotilla.

We

were escorted by destroyers, cruisers and other battle ships as part of

the American 'Western Task Force' invading

Utah & Omaha beaches,

while the British and Canadian

'Eastern Task Force' invaded Gold, Juno &

Sword.

SS Princess

Maud carried several hundred Yankee soldiers, mainly demolition men to clear

beach obstacles in advance of the initial

assault troops. The obstacles

were designed to hinder the progress of the invading forces

as they approached and crossed the landing beaches.

The obstacles included

ramps, hedgehogs, stakes and element C. These brave men had their own specialised

'Landing Craft Mechanised' (LCMs) to transport

them to the beaches, where they

would face enemy machine gun fire and mortar bombs, while they went about their

work. Our job was to

pick up American troops

from other troop carriers and transport them to predetermined positions on the

landing beaches.

The crossing of the English

Channel was rough and we hoped it would settle before we beached our small vulnerable craft.

As we neared France, Allied bombers, with fighter escorts, dropped bombs to soften

up the landing beaches in advance of the initial assault force. We could see enemy ack ack

fire in response. Unbeknown to us at the time, a few thousand paratroopers had

already been dropped behind enemy lines.

We reached our rendezvous

point about 03.00 hours on June 6th. American troops of the 1st

battalion, 116th US Infantry loaded into LCMs secured alongside. At about 0400 hrs,

we manned our craft and were lowered into the rough waters.

Manoeuvring our flat bottomed craft was difficult with 3 foot waves and a heavy swell. Water

sprayed over our boat as we headed for the Empire Javalon, a nearby LCA/troop

carrier. We were hoisted up to embark men of the US 5th

Ranger Battalion. We reached our rendezvous

point about 03.00 hours on June 6th. American troops of the 1st

battalion, 116th US Infantry loaded into LCMs secured alongside. At about 0400 hrs,

we manned our craft and were lowered into the rough waters.

Manoeuvring our flat bottomed craft was difficult with 3 foot waves and a heavy swell. Water

sprayed over our boat as we headed for the Empire Javalon, a nearby LCA/troop

carrier. We were hoisted up to embark men of the US 5th

Ranger Battalion.

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' opposite, shows

the 519 LCA

Assault

Flotilla was due to go to Juno beach but

for D-Day

was loaned to

the Americans at

Omaha].

Once fully loaded with our

complement of troops, we were lowered into the water. On return to the

vicinity of our own ship,

SS Princess Maud, the LCMs were still loading the demolition teams.

Their craft were

tossed up and down like corks, banging against the ship's side with securing lines parting and

being replaced. The men looked precarious,

as they climbed down scaling ladders

with their heavy gear on their backs.

The difference between the British and

American embarking

procedures was dramatic in these rough conditions. However, the British

procedures were not without their own problems. One of our craft, by then fully loaded

with troops, was floundering and in danger of sinking. Although not apparent

until the craft was back in the water, she had been holed during hoisting aboard

the Empire Javalon. Her

crew refused to hoist her back! Fortunately, the

coxswain remained calm and

circled Princess Maud until everyone, troops and crew, disembarked. Shortly

after, the LCA nose-dived beneath the waves.

As daybreak broke, we could

see the awe-inspiring sight of thousands of ships and craft preparing to transport the troops and their equipment to the

landing beaches. The battleships, cruisers

and rocket craft bombarded the coast to

further soften up the enemy defences. The time came

for our remaining 5

craft to make for our designated landing beaches. At first we made

good progress but our Flotilla Officer’s (FO's)

craft took on water and started to go down by the bows. In an attempt to steady the craft and reduce water ingress, the

coxswain manoeuvred the craft to put its stern to the weather but the unstable LCA

capsized. As daybreak broke, we could

see the awe-inspiring sight of thousands of ships and craft preparing to transport the troops and their equipment to the

landing beaches. The battleships, cruisers

and rocket craft bombarded the coast to

further soften up the enemy defences. The time came

for our remaining 5

craft to make for our designated landing beaches. At first we made

good progress but our Flotilla Officer’s (FO's)

craft took on water and started to go down by the bows. In an attempt to steady the craft and reduce water ingress, the

coxswain manoeuvred the craft to put its stern to the weather but the unstable LCA

capsized.

[Photo; Leonard Albert King].

The

Flotilla Officer (FO), crew and most of the soldiers

were picked up by the remaining 4 boats and we proceeded towards the beach. As we drew closer, the more

hazardous became our position

from shells, mortars and machine gun fire. Many craft around us succumbed to the deadly fire, some

capsizing. There were many casualties but we had to focus on our mission. Our 4

remaining craft successfully disembarked our troops and succeeded in un-beaching; but not without damage. One of our

boats was riddled with bullet holes, with

a 4 inch shell embedded in a battery, which put the port engine out of action.

Some

craft from our

flotilla were

picked up by the Prince Charles, an LCA/troop carrier, which happened to be quite close to the beach attempting to rescue

some of her own badly damaged LCAs. Another

of our LCAs was picked up by Princess Maud, as

the crew baled out as though their lives

depended upon their labours. Our fourth craft, Nobby’s,

was picked up by yet another ship.

We

met up with Nobby that

evening in Cowes

on the Isle of Wight. The bow of his craft was badly mangled

and in the relative safety of home waters, we found it difficult to accept

the reality of the noise, violence, death and destruction of total war

we had witnessed. We had a rough time but we survived. Others

performing similar duties, were

not

so lucky. We

met up with Nobby that

evening in Cowes

on the Isle of Wight. The bow of his craft was badly mangled

and in the relative safety of home waters, we found it difficult to accept

the reality of the noise, violence, death and destruction of total war

we had witnessed. We had a rough time but we survived. Others

performing similar duties, were

not

so lucky.

[Photo;

Royal Navy Commandos of the Landing Craft Obstacle

Clearance Units running to get clear while obstacles are blown up at

La Riviere. Some of the invasion ships can be seen on the horizon. ©

IWM (A 23993). Similar work was undertaken by US Engineers on Omaha

and Utah].

One of our lads, 'Shorty' Griffin,

was reported missing

but later found to be in Hospital having been plucked from the sea by an LCT. There was little time for rest and recuperation. Next day, 4 new LCAs

were delivered, replacing those lost or damaged

and we sailed round to Portland for more troops.

Post D-Day

Our second trip to Normandy was on June

10th, when we carried military police (MPs), doctors and medical orderlies

to Utah, the second American beach. It was less hazardous this time,

since the enemy beach defences had been cleared, although we were still

vulnerable to mines, shells and strafing by the Luftwaffe.

We arrived about 0400 hrs as landing craft of many

types unloaded stores, munitions

and supplies. We landed on an ebbing tide, so quickly

disembarked our human cargos to avoid being stranded high and dry. Despite our

best efforts, 2 of our craft were stranded until the next tide. On D-Day, these craft would have been picked off like sitting ducks by shell fire

and mortar bombs. However, on this trip, it was more of an inconvenience, as vital

landing space was unnecessarily taken up on the busy beachhead.

Mine clearing work was still

in progress off the beaches and one

mine was detonated fairly close to our position. We were hoisted

back on board our mother craft and spent the night just offshore. An LCT came

alongside loaded with British Troops of the Pioneer Corp, who had previously had a wet landing when their craft stuck on a sand bar a few

metres from the shore. At dawn, we took them to their landing beach, this time giving them a

dry landing! Amongst their number were 2 stretcher cases and a soldier with

a broken arm. We carried them back to England

for hospital treatment.

Back at Portland,

we embarked another 850 men of US Army on to

our mother ship and safely delivered them to France on June the 13th. It

was an uneventful round trip although, on the return leg, we zig-zagged to avoid

a reported U-boat. With 3

days ashore, we went on the razzle and to the dances! The 2 stranded LCAs returned safely. At 0200 on June the 18th, we departed with more American

troops, landing them without incident in France at about 11.00 hrs, this time directly on

to a pontoon pier.

En route for

Newhaven, we saw a doodlebug fly over in the general direction of England

and heard on the radio that one of our ships had been

torpedoed, although 3

destroyers were on hand to pick up survivors. Back at Newhaven,

we picked up about 800 British soldiers, Welsh Guards and Pioneers. We made for

Portsmouth, where we joined a convoy

to the British/Canadian sector near Arromanche,

which was now served by a

harbour made of concrete blocks - one of two 'Mulberry Harbours.'

Next morning

we joined a homeward convoy, during which we

saw minesweepers in action clearing

mines laid by the Germans during the hours of darkness. Two were detonated in the middle

distance. After visiting Netley on the approaches to Southampton, to store up and refuel,

we proceeded to Cowes for a welcome spell of shore leave.

We

then transported

British troops from the North and South Staffs and the Royal Norfolks of Monty’s 2nd

Army. We passed by the protruding bows of two sunken Liberty Ships; a reminder that

easy passage across the channel could not be taken for granted. We disembarked at noon on June the 28th, men and bicycles. On our convoy home, another LCA/troop

carrier, the Maid of Orleans, was sunk by a mine. Five men in the engine room were killed but

the remaining crew were picked up by destroyers.

We docked at Cowes and later

embarked a Leicester Regiment and 6 patrol dogs at

Southampton. The weather was pretty rough but we successfully landed our troops,

returned to Southampton, embarked American infantry, electricians and

20 nurses; the first women to come aboard and

landed them all on the beaches, since the pontoons we

had been using were high and

dry. Some craft became stuck on

the sand but we returned to our mother craft, sailed home to Cowes and enjoyed some shore leave.

On 12 July, we picked up 450 British troops, our official

carrying capacity, as opposed to the

800 or more on previous trips. We landed them on 14 July in comparative peace,

needing only 3 return trips for each craft.

Len's diary ended at this

point, most likely because the trips to France had become much safer and routine.

The use of LCAs continued until larger ships could safely use functioning ports

captured from the Germans.

Postscript

In Nov 1944, Acting Temporary

Leading Seaman, Leonard King, service no C/JX 379424, was awarded a DSM (Distinguished Service Medal) for an action

during Operation Infatuate, the assault on the

heavily defended island of Walcheren in the Scheldt estuary. While the island

remained in enemy hands, the Allies were unable to use the port of Antwerp which

had fallen to them. It was of great strategic importance in the supply chain to the Allied

armies, by then advancing towards Germany.

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Acknowledgements

We're very grateful to Ray King for sight of his brother's diary on which this

webpage is based. The text was approved by Ray before the webpage

was published.

Photos and maps have subsequently been added.

|