To each side of us other DD tanks were launching. To my right and behind me I

saw Captain Noel Denny’s tank as it came down the ramp and into the sea. It

straightened up and began to make way, but behind it I could see the large bulk

of its LCT creeping forward. The distance between them closed and in a very few

minutes the inevitable happened. The bows of the LCT struck the DD tank and

forced it under the water. The tank disappeared beneath the LCT and was never

seen again. Captain Denny escaped and was picked up but the tank was

sunk and the rest of the crew was lost. There was nothing anybody could do.

These were our first casualties.

To each side of us other DD tanks were launching. To my right and behind me I

saw Captain Noel Denny’s tank as it came down the ramp and into the sea. It

straightened up and began to make way, but behind it I could see the large bulk

of its LCT creeping forward. The distance between them closed and in a very few

minutes the inevitable happened. The bows of the LCT struck the DD tank and

forced it under the water. The tank disappeared beneath the LCT and was never

seen again. Captain Denny escaped and was picked up but the tank was

sunk and the rest of the crew was lost. There was nothing anybody could do.

These were our first casualties.

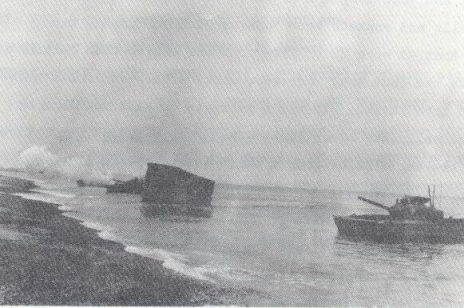

[Photo; Tank disembarking from an LCT. The angle

of the ramp was crucial to avoid a deluge of water over the top of the

waterproof screen].

We battled on towards the shore through the rough sea. We were buffeted

unmercifully, plunging into the troughs of the waves and somehow wallowing up

again to the crests. The wind was behind us and this helped a little. The noise

of battle continued and shells and rockets were passing over our heads towards

the German defensive positions but we were also aware that we were under fire

from the shore. The Germans had woken up to the fact that they were under attack

and had brought their own guns into action.

It was a struggle to keep the tank on course but gradually the shoreline

became more distinct and we could see the line of houses which were our targets.

Seasickness was by now forgotten. It took over an hour of hard work to

reach the beach and it was a miracle that most of us did. As we approached, we

felt the tracks meet the shelving sand of the shore, and slowly we began to rise

out of the water. We took up our posts to deflate the screen, one man standing

by each strut. When the base of the screen was clear of the water the struts

were broken, the air released and the screen collapsed. We leapt into the tank

and were ready for action.

Action

Action

"75, HE, Action - traverse right, steady, on. 300 - white fronted house-

first floor window, centre". "On" "Fire!"

Within a minute of dropping our screen we had fired our first shot in anger.

There was a puff of smoke and brick dust from the house we had aimed at, and we

continued to engage our targets. Other DD tanks were coming in on both sides of

us and by now we were under enemy fire from several positions which we

identified and to which we replied with 75mm and Browning machine gun fire.

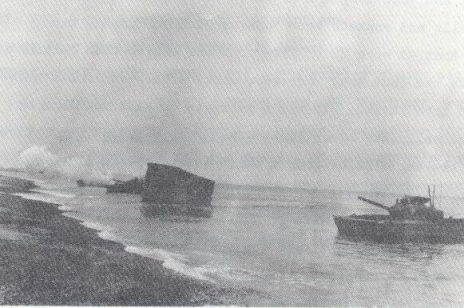

[Photo; Tanks approaching the shore. Those with

their screens lowered are already firing or preparing to fire].

The beach, which had been practically deserted when we had arrived, was

beginning to fill up fast. The infantry were wading through the surf and were

advancing against a hail of small arms fire and mortar bombs. We gave covering

fire wherever we could and all the while the build up of men and vehicles

continued.

Harry Bone’s voice came over the intercom, "Let’s move up the beach a bit -

I’m getting bloody wet down here!" We had landed on a fast incoming tide, so the

longer we stood still the deeper the water became. As we had dropped our screen,

the sea was beginning to come in over the top of the driver’s hatch and by now

he was sitting in a pool of water. The problem was that the promised mine

clearance had not yet taken place, so we had to decide whether to press on

through a known mine field, or wait until a path had been cleared and marked.

Suddenly, the problem was solved for us. One particularly large wave broke

over the stern of the tank and swamped the engine, which spluttered to a halt.

Now, with power gone, we could not move, even if we wanted to. Harry Bone and

Joe Gallagher emerged from the driving compartment, soaking wet and swearing.

More infantry were coming ashore, their small landing craft driving past us

and up to the edge of the beach. There was quite a heavy fire fight in progress

so we kept our guns going for as long as possible, but the water in the tank was

getting deeper and we were becoming flooded. At last we had to give up. We took

out the Browning machine guns and several cases of .3 inch belted ammunition,

inflated the rubber dinghy and, using the map boards as paddles and began to

make our way to the beach.

We had not gone far when a burst of machine gun fire hit us. Gallagher

received a bullet in the ankle, the dinghy collapsed and turned over and we were

all tumbled into the sea, losing our guns and ammunition. The water was quite

deep and the sea was flecked with the traces of bullets all around us. We caught

hold of Gallagher who was swearing like a trooper and we set out to swim and

splash our way to the beach. About half way there I grabbed hold of an iron

stake, which was jutting out of the water, to stop for a minute to take a

breather. Glancing up I saw the menacing flat shape of a Teller mine attached to

it; I rapidly swam on and urged the others to do so too!

Somehow, we managed to drag Gallagher and ourselves ashore. We got clear of

the water and collapsed onto the sand, soaking wet, cold and shivering. A DD

tank drove up and stopped beside us with Sergeant Hepper grinning at us out of

the turret. "Can’t stop!" he said, and threw us a tin can of self heating soup

from the emergency rations each tank carried. We pulled the ring on top of the

tin and as though by magic it started to heat itself up. We were very grateful

for this and, as we lay there on the sand in the middle of the battle taking

turns to swig down the hot soup, we were approached by an irate Captain of Royal

Engineers, who bellowed; "Get up, Corporal – that is no way to win the Second

Front!"

Tankless!

He was absolutely right, of course. Rather shamefacedly we got up, moved

further up the beach and found some medical orderlies into whose care we

delivered Joe Gallagher, who cheered up considerably when someone told him he

would be returning to Blighty as a wounded "D Day Hero". We left him at the

Field Dressing Station and moved on. We had only our pistols with us but found a

discarded Sten gun and some magazines. Attaching ourselves to a section of the

South Lancashires, we made our way inland.

The beach, by now, was a very unhealthy place to be. It was under intensive

small arms and mortar fire, mines were exploding and being detonated by our own

mine clearing services and all the time the build up of troops and vehicles

continued, making it a very crowded area. Clearly, we were not much use to the

infantry in our unarmed state, so I found the Royal Navy Beach Master and

reported our presence to him. He was a very busy man at the time and advised me

to: "Get off my bloody beach!" We made our way to the road which ran parallel to

the sea, some five hundred yards inland, and there we met up with some other

un-horsed tank crews.

I could not help feeling a bit unwanted at that stage. There was plenty of

action taking place but there was not a lot that we could do to influence the

course of the battle and nobody seemed keen to invite us to join in. Of course,

we had already played our part, and we could look back with some satisfaction.

We had done what most people had thought impossible, we had swum a 32 ton tank

through 5000 yards of savagely rough sea and had given that vital support to the

infantry to enable them to do their job of clearing the beach.

I could not help feeling a bit unwanted at that stage. There was plenty of

action taking place but there was not a lot that we could do to influence the

course of the battle and nobody seemed keen to invite us to join in. Of course,

we had already played our part, and we could look back with some satisfaction.

We had done what most people had thought impossible, we had swum a 32 ton tank

through 5000 yards of savagely rough sea and had given that vital support to the

infantry to enable them to do their job of clearing the beach.

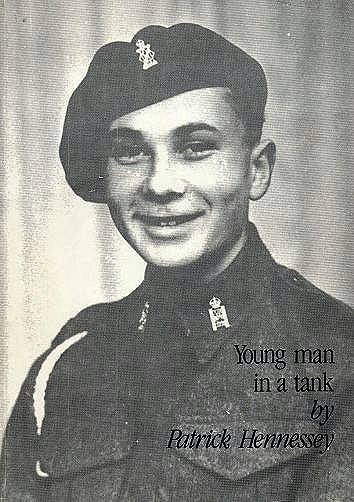

[Photo; The author, Patrick Henessey].

On reflection, I had learned a valuable lesson from the events of that

morning. Sgt. Hepper, for instance, had clearly not been deterred by the

prospect of mines on the beach and had driven his tank ashore, accepting the

risk. If I had used initiative and done the same, our tank would not now be

standing submerged some 150 yards out in the sea. The RE Captain too, had the

right idea of ‘press on, regardless’. In the heat of battle it really does not

pay to sit back and weigh up the pros and cons of a situation, it is quick

decision and immediate action which brings results. I mentioned these thoughts

to Harry Bone, whose only comment was: "Bugger that! – if we had hit a mine, I

would have been sitting right on top of it".

The beach was still a scene of frantic activity. Landing craft were coming

in, depositing their loads of men and vehicles, then backing out to sea again.

The area was swept by machine gun and mortar fire and snipers were busy from the

windows of the houses. Shells and mortars were kicking up clouds of sand, the

noise level remained very high, and the infantry were taking a lot of

casualties. I saw death for the first time that day and also for the first time

I came face to face with the German Army.

About two dozen prisoners were being

marched to the beach, hands held aloft, some were wounded, all looked shocked

and frightened. They were a scruffy crowd, not at all the ‘Supermen’ we had been

led to believe were opposing us. Most professed to be White Russians or Poles,

but there were a few who were arrogantly German. Eventually, we were found by

Major Wormald, who directed us to make our way to the village of Hermanville. We

were delighted to see him and to know that he had survived the landings. As he

drove off in his tank, we felt a return of confidence as we started the three

mile trek to Hermanville.

At Hermanville we settled into a barn and some farm buildings, and eventually

what was left of ‘A’ Squadron came together. We had not suffered a great number

of casualties in terms of men lost, but we only had 5 serviceable tanks

remaining from the 21 which had launched that morning. Each of the surviving

crews had their own dramatic stories to tell of that unforgettable day.

We learned that our sister Regiments, the 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards and the

Staffordshire Yeomanry, had decided that the sea was too rough for DD tanks to

operate and had come in dry-shod. Our Regiment was the only one to attempt the

sea-borne assault on Sword beach. ‘A’ and’ B’ Squadrons had motored in over 5000

yards of troubled water in a force 8 gale! This was a far greater distance than

ever thought possible especially in such high winds and with sea conditions far too severe for DD tanks.

Thus, we had written another page in the honourable history of our Regiment and

Major Wormald had earned a well deserved DSO for his part in the Landings.

We spent a number of days in Hermanville where we dried out and received new

bedding and equipment from a stores vehicles that had caught up with us. These

were largely uneventful days as the battle moved inland but we had one exciting

episode when we removed a couple of snipers from the nearby church tower.

I acquired a parachutist’s bicycle and on the morning of 7th June

I returned to the beach to see what could be salvaged from our tank. A secure

beachhead had been established and there was no firing. It was still very busy

with the arrival of stores and backup troops to support our advancing forces.

The tide was out and I could see our tank standing forlornly in about 3 feet of

water. All items of value and our personal possessions had been taken. Harry

Bone was already there having somehow got hold of a motorbike. He roundly cursed

the infantry whom he accused of stripping our tank, but his mood improved

dramatically when he found two jars of rum which he salvaged and conveyed back

to Hermanville.

Conclusion

Pat gives no summarising remarks about his war experiences at the end of his

book. He fought his tank through the rest of the campaign in France,

Belgium, Holland and the first battles in Germany, getting promoted to Sergeant

on the way and in April was selected for officer training. After commissioning out of Sandhurst in 1946, he continued to serve in the Army until 1951, when he

transferred to the RAF. He retired as a Group Captain in 1984 after which

he penned these wartime experiences.

His son is a serving RN Commodore and

his grandson has recently left the Grenadier Guards after serving in Iraq and

Afghanistan. Clearly writing, as well as military service, runs in the

family as the grandson (also called Patrick Hennessey) has recently recounted

his operational experiences in a much-acclaimed book called "The Junior Officers

Reading Club" (published by Penguin Books in 2009). [John

Ogden]

To each side of us other DD tanks were launching. To my right and behind me I

saw Captain Noel Denny’s tank as it came down the ramp and into the sea. It

straightened up and began to make way, but behind it I could see the large bulk

of its LCT creeping forward. The distance between them closed and in a very few

minutes the inevitable happened. The bows of the LCT struck the DD tank and

forced it under the water. The tank disappeared beneath the LCT and was never

seen again. Captain Denny escaped and was picked up but the tank was

sunk and the rest of the crew was lost. There was nothing anybody could do.

These were our first casualties.

To each side of us other DD tanks were launching. To my right and behind me I

saw Captain Noel Denny’s tank as it came down the ramp and into the sea. It

straightened up and began to make way, but behind it I could see the large bulk

of its LCT creeping forward. The distance between them closed and in a very few

minutes the inevitable happened. The bows of the LCT struck the DD tank and

forced it under the water. The tank disappeared beneath the LCT and was never

seen again. Captain Denny escaped and was picked up but the tank was

sunk and the rest of the crew was lost. There was nothing anybody could do.

These were our first casualties.