|

HMS Empire Battleaxe - Landing

Ship Infantry (Large).

This is the story of HMS Empire Battleaxe

based on the recollections of Royal Marine Corporals, Norman Sam Moss, PO/X107607 and William

Robert Jones, CH/X113254, who served in Combined Operations in WW2. Both wrote an

account of their experiences. Sam's

was entitled 'My Bit During World War Two' (2006) and Bill's

was modestly entitled 'Bill’s Brilliant Military Career' (2004)!

[Photo; HMS Empire Battleaxe, Landing Ship

Infantry (Large), August 1, 1944, Greenock. © IWM (A 25062)].

Sam and Bill were both coxswains in 537 LCA Flotilla onboard Landing Ship Infantry

SS Empire Battleaxe, later designated HMS Empire Battleaxe. She

was a Landing Ship Infantry (Large) or LSI (L) with a capacity to carry 1,000

fully armed troops, 18 Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) and 1 Landing Craft

Mechanised (LCM). Each LCA had a capacity of around 30 troops + a crew of 4.

The

Empire Battleaxe

The SS

Empire Battleaxe

was

one of 12 or so bearing the 'Empire' name. She was built in the

USA to an original British design but modified and adapted for her new role as a

troop carrier. The

most obvious modifications were the use of diesel power in place of steam and

welded plate construction instead of rivets. Both reduced the time taken in

construction and fitting out - important attributes for the urgently required so

called liberty ships provided by the Americans under the lend/lease scheme.

The 'Empire' ships were built to carry eighteen

Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) and to

accommodate about one thousand troops. They had a speed of 14 knots. Some of the

ships had provision for an additional landing craft, usually an LCM (Landing

Craft Medium), capable of transporting vehicles to the beaches.

The LCAs were lifted on and off the vessels on hoists (davits) and the LCMs were

lifted

onto the stern deck by crane. This additional craft was normally carried when operating

with American troops. The ship was manned by Merchant Seamen with

Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (DEMS) personnel to operate the

four inch gun towards the bow and 0.8 inch Oerlikons mounted on the upper deck.

These ships formed the majority of

the infantry carrying ships in the three British invasion forces being formed

for the Normandy landings; G

for Gold, J for Juno and S for Sword, which included the Empire

Battleaxe. ‘S’ Force also had HMS Glenearn, a converted 18 knot cargo

liner of about 10,000 tons, carrying two LCA Flotillas of twelve craft each.

LCAs

Carried by the Empire Battleaxe

The

LCAs were especially designed for

their intended purpose of landing men and

supplies directly onto the beaches of enemy occupied territory. They were

occasionally incorrectly referred to as barges, perhaps because the use of

barges had been contemplated at one time. They were well designed for their

intended use and built in small shipyards with previous experience of yacht and small boat building.

The craft were forty four feet long, ten feet wide,

flat bottomed and weighed ten

tons. They were designed to carry a platoon of 30 to 33 men in three rows of ten

or eleven men on three thwarts running the length of the main part of the boat.

The troops were usually seated in the order in which they normally marched. The craft were forty four feet long, ten feet wide,

flat bottomed and weighed ten

tons. They were designed to carry a platoon of 30 to 33 men in three rows of ten

or eleven men on three thwarts running the length of the main part of the boat.

The troops were usually seated in the order in which they normally marched.

[Photo; An LCA at rest].

There were two steel doors in the bow of the landing craft and

in front of these was the ramp. On arrival on the beach, the ramp was lowered and

the bow doors opened to allow disembarkation, rapid disembarkation when under

fire. The ramp was controlled by two ropes. At the front right was a

compartment about two feet by three

feet for the coxswain, with a steering wheel in front of him and, to the right, two

engine telegraphs going back to the engine compartment at the rear. compartment about two feet by three

feet for the coxswain, with a steering wheel in front of him and, to the right, two

engine telegraphs going back to the engine compartment at the rear.

In order to obtain a good view ahead and alongside, the coxswain

usually stood with his head and shoulders above the protective steel front and

sides. However, when the craft came under fire, he could sit down, close the lid over the

top of his position and peer out through small slits forward and to the right.

On the left of the boat, in line with the coxswain’s compartment, was a position

for a Bren Gun or similar weapon able to fire forward from behind the armour

plating.

[Photo; a view of an LCA showing a platoon of

men sitting on the thwarts. In the foreground one of the front steel doors

is in the open position. Part of the coxswain’s compartment can be seen on

the left and the compartment for a weapon is on the right. This is an early

model of an LCA probably 1941 or 1942].

Over the top of the compartment for the

platoon of troops, running down each side of the boat, was a gunwale or

decking about two feet wide, under which two sections of troops would sit on

their thwarts. The five or six feet of space between the two gunwales was

normally open.

To the rear of this area was the engine

compartment with two V eight petrol engines. The stoker sat in the middle,

watching the telegraphs indicating the coxswain’s requirements and operating

the throttles and gear levers as required. Behind this compartment were the

fuel tanks, the twin

propellers, two rudders and exhaust pipes. On the deck

above the engine compartment were mooring cleats, a hoisting eye, engine air

inlets, fuel filling inlets, a kedge (an anchor from the rear) and an access

hatch for the stoker. propellers, two rudders and exhaust pipes. On the deck

above the engine compartment were mooring cleats, a hoisting eye, engine air

inlets, fuel filling inlets, a kedge (an anchor from the rear) and an access

hatch for the stoker.

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' which shows the

disposition of the Empire Battleaxe and her LCAs].

Running the full length of the boat was a large timber beam

forming the keel of the boat, to which was fixed two lifting eyes at the

front and rear to enable the craft to be hoisted onto a parent ship. About this

keel, the boat was constructed of double diagonal mahogany planking with a

waterproof membrane between. The area occupied by the troops, to the rear of the

front steel doors, was lined with three sixteenths inch thick steel sheeting,

reckoned to be bullet proof. The inside walls were lined with cork to increase

the craft's buoyancy.

With the engines close to the

rear, the boat was capable of operating

silently on low throttle.

Formation of 537 LCA

Flotilla

The Empire Battleaxe sailed up to the Cromarty Firth off the

north east coast of Scotland, where the Flotilla commenced more realistic and

serious training under normal sea-going conditions. It was vital to practice the

hoisting of the craft onto the ship and lowering them into the water.

Significant forces were involved

in hoisting and lowering the 10 ton craft, even in calm weather. But in rough

weather the weight of the craft was instantly transferred from the davit cables

to the sea and back to the cables as the sea fell away. It was dangerous work as

the crew struggled

to control the large multi-sheath pulley blocks hooked into the LCA’s lifting

eyes.

When the craft were being lowered, the ship was usually at anchor

with the tide swinging the ship about the anchor chain. As a result, the sea

constantly moved from the front to the rear of the ship. In these conditions, it

was very important to unhook the craft at the stern first then work forward. This

allowed the engines to be used to create space to manoeuvre the craft and to avoid collisions. When the craft were being lowered, the ship was usually at anchor

with the tide swinging the ship about the anchor chain. As a result, the sea

constantly moved from the front to the rear of the ship. In these conditions, it

was very important to unhook the craft at the stern first then work forward. This

allowed the engines to be used to create space to manoeuvre the craft and to avoid collisions.

[Map courtesy of Google. 2019].

It was

normal practice for the full complement of troops to be on board during these

procedures. The stoker fired up the engines at the correct moment to ensure that cooling water was circulating, while the

remainder of the crew endeavoured to avoid a collision with the mother ship.

During the two months or so we spent in these northern waters, we

took part in two large exercises involving many other vessels, including a

cruiser. The Empire Battleaxe sailed into the Moray Firth and anchored some ten

to twelve miles North of Burghead Bay. The fully loaded LCAs were successfully

lowered and the troops landed just to the West of Burghead.

On leaving the mother ship, the

craft formed up in a two column line astern heading for the beach. Only when all

craft were in position did they

begin their approach. At a distance of about a mile from the intended landing

zone, the craft would deploy to line abreast to hit the beach together, ensuring

maximum safety and fire power.

The compass bearing, as the flotilla moved towards the Scottish shore, was

identical to the bearing used a few months later on the approach to the Normandy

beaches. To replicate the forthcoming Normandy landings, 537 Flotilla took up the most easterly

position on the beach, with the attendant hazard of rocks at Burghead. In

this way the reality of D-Day would be very similar, including a warning to keep

clear of the River Orne due to hazards. The planning and training were meticulous. These

exercises were the first time Force ‘S’ came together to rehearse the actual

landings.

The weather and sea conditions were

poor during the training exercises, with postponement a distinct possibility but,

in the event, the experience of the rough conditions also emulated the

conditions on D-Day. The object was to land the troops as safely and comfortably

as possible onto their predetermined landing beach and then to immediately winch the craft off the beach,

using the kedge anchor and reverse thrust from the engines, before returning to the

mother ship or to some other location as directed by the Flotilla's HQ ship. To

achieve the de-beaching manoeuvre, the

coxswain ordered the craft’s kedge anchor to be dropped over the stern on the

approaches so it could be used to pull against during de-beaching.

With

unpredictable tide, sea and wind conditions, the stern could swing sideways

causing the craft to "broach to", during which it ended up parallel to the beach. In this position there

was insufficient water depth for the propellers to operate, which compounded the

problem. To reduce the risk of this happening, two deck hands ran a rope from

each of the two rear bollards onto the beach at an angle, effectively holding

the craft at a right angle to the beach in conjunction with the kedge anchor. If all else failed, it was over the side and into the sea to

push the boat back into the correct position.

To minimise the difficulties, landings often took place on a

rising, incoming tide just before high tide. This might vary dependant on the

slope and other characteristics of the beach but in most conditions, slack tidal water

offered the most favourable landing conditions.

When not involved in the major

group training exercises, the flotilla undertook

its own programme of training. The only occasion the weather conditions

prevented the LCAs returning to their mother ships occurred on a mock landing

near Nigg, on the north side of the entrance to Cromarty Firth. The flotilla had

five or six miles to travel against a very strong westerly wind, which whipped up

the enclosed water of Cromarty Firth into steep waves about three feet high. The

waves broke over the crafts' front ramps and, despite tacking, they failed to make

progress. After a couple of hours, the flotilla turned around and made its way back to

the little town of Cromarty, where they found accommodation for the night.

On another occasion whilst in Cromarty Firth, some craft moored

in the little harbour of Invergordon. The crews were taken by surprise when a

spring tide left little water in the harbour and some of the craft were left

hanging on their mooring lines!

There were many kinds of landing craft designed for particular

specialised functions, including the Landing Craft Obstacle Clearance Unit, LCOCU.

Instead of carrying regular fighting troops, they carried a section of Royal Marine Commando Divers, equipped to locate and clear underwater obstructions,

using explosives. The Germans' steel and concrete obstructions were designed to

impede or hole approaching landing craft as they attempted to beach. The LCOCUs

had a stored-away ladder that fitted over

the front ramp so divers could descend into the water. There was also an

'asdic', for detection of underwater obstacles, fitted to the left front of the

craft. It could be lowered into the water when required. The asdic was powered by

a line of batteries between the right hand thwart and the right hand wall of the

boat. Supplies of explosives, detonators and buoys to mark any cleared channel

were also part of the cargo.

The time came for the Empire Battleaxe to leave Invergordon and,

after a detour to Hebburn on the River Tyne for a gun replacement, we sailed back

to the Isle of Wight on the south coast of England by a circuitous route

northwards via the east coast of Scotland, westwards through the Pentland Firth and

southwards down the west coast of Scotland, through the Irish Sea and east around Lands End to

the Solent, to lie between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. Training exercises

continued with a landing on the south coast of England near Littlehampton.

During the night, after leaving the Solent, the force sailed towards the French

coast to test the reactions of the Germans. There was none.

At the end of May, Bill's craft sailed to Littlehampton for special

exercises with Commando divers, who were billetted in the town. After three days

of practice on the beach west of Littlehampton, they loaded all their gear onto

the craft, resulting in it settling several inches lower in the water than

normal. The journey back to the Empire Battleaxe was rough at times and 8 inches

of water was pumped out of the bilges.

As D-Day approached, the crew of Bill's LCOCU were informed that she

was to be manned by volunteers, because of the high risk of casualties arising

from enemy fire and the explosive cargo on board. There was no appetite amongst the crew

to back-out after undergoing months of training. On Friday 2nd of June, 1944,

the ship was sealed and nobody was allowed ashore without special permission and

an escort.

On the main deck of the Empire

Battleaxe, there was a model of the flotilla's landing beach with the positions

of three lines of steel and concrete obstructions clearly marked. Intelligence

indicated that the third line was still under construction and one in three of

the obstructions had a teller mine fixed to the top. Each LCOCU was allocated a

unique serial number in the three hundreds. A photograph album showing the

appropriate part of the coast line, taken from sea level, was also provided to help in identifying the landing

area. At the last minute, D-Day planned for June 5th was postponed by a day, to

the considerable discomfort

of all confined to their vessels.

D-Day;

Sam's Account

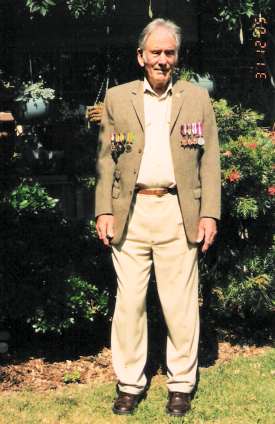

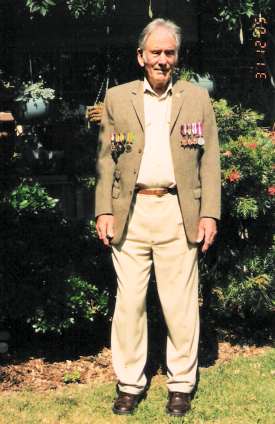

Norman

Sam Moss, PO/X107607 (Sam). Sam's

story of joining up and early training is recorded below these

recollections

of his association with the

Empire Battleaxe.

If you wish to read it first, click here. Norman

Sam Moss, PO/X107607 (Sam). Sam's

story of joining up and early training is recorded below these

recollections

of his association with the

Empire Battleaxe.

If you wish to read it first, click here.

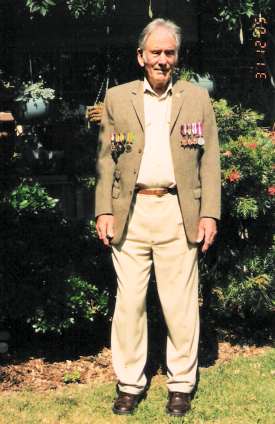

[Photo; Sam Moss].

Of D-Day morning on board the

Empire Battleaxe,

Sam recalls,

"The crews of 537 LCA Flotilla were all summoned to the main deck

and given photographs of our individual landing areas. Our LCA was to go ashore

on Queen Red sector of Sword beach. We were told our training was at an end.

This was it. The real thing. God bless you all! Few of us slept well that night.

We were all nervous about what lay ahead of us come the morning.

I was on deck early as we made our way across the English

Channel. Within minutes, a nearby destroyer, HNoMS Svenner (G

03), was hit amidships and sunk by torpedo boats 12 miles west of Le Havre at

0535 hours. I watched in disbelief as she cracked in two and vanished in

what seemed minutes. We all stood watching, our mouths suddenly dry. Was this

really happening?

We were due at the beach sometime

between 7.30hrs and 8.00 hrs and at about 6.30hrs a Tannoy announcement ordered us to man the

boats. We had some 10 miles to go as we loaded the troops, lowered away, unhitched,

formed up and got underway for our designated beach. The sea was quite rough and

every man was issued with a few sick-bags. Very few of them went unused that morning.

15 inch shells whistled overhead at an alarming rate and a

constant hiss filled the air. Incoming fire hit the water around us as

we made our approach. Having discharged our troops, we weaved our way back to our

mother ship through crowded waters, as vessels of all kinds went about their

individual tasks

We

embarked more troops from Battleaxe and headed

once more towards Sword beach. This became a journey to hell and to this day

continues to give me nightmares and doubtless many other veterans too, who were

witness to the scenes. The sights are impossible to forget. They

were immensely distressing for everyone. I'll never know how I managed to get my

craft back to sea again that day!

This time we did not return to the Empire Battleaxe, since she had been

recalled to England to embark more troops. We received a message by semaphore

ordering us alongside another troopship to pick up a contingent of Royal Naval

Commando. We were given the co-ordinates for our landing beach and, having

successfully landed the troops, we went full astern and hit one of the beach obstacles, which

holed our LCA forward of the engine room. But luck was still with us. A three inch hole

had been punched through the hull just above the water line. We filled it with blankets

and, with the bilge pumps on full blast, we returned to the mother ship.

Following our next journey to the beach,

we received permission from

the Beach Master to go high and dry, allowing us to carry out essential repairs.

I sent two of our crew off to forage for anything that might prove useful. The

items they returned with so quickly surprised me. Should I ever be stranded on a desert island, I would hope

to have those same two crew members with me!

When the repairs were done, the

sea was too rough to launch, so we decided to

remain until dawn of the following day. Having been without sleep for a long

time, we dug a trench and covered ourselves with our ground sheets. We were all

close to exhaustion. The restful sleep we so needed did not happen, since all through the night, we

were constantly disturbed by sand flies. At least we missed the shelling and

small arms fire that was going on around us that night. Dawn arrived and on a

high tide, with some pushing and heaving and our engines on full

throttle astern, we made it out to sea. We reported back to our flagship HMS Largs,

which commanded all sea movements in Sword beach area. We tethered our craft to

her and gratefully accepted a hearty meal of stew with cups of tea in abundance.

Having refuelled, we were given orders to continue ferrying troops and

supplies to the beach for as long as required. Each night, our LCA was refuelled

and maintenance carried out to ensure our craft was ready for

service at dawn of the following day. We spent each night on board HMS Largs,

although sleep was difficult with the 24/7 activity. It was just part of the job

and I've no recollection of anyone moaning about their lot. HMS Largs was

a good ship to operate from. All onboard were looked after and cared for and we

had at least one hot meal a day, with as much tea as we could drink.

At each pre-dawn briefing we were given our orders for the day

ahead, which usually entailed meeting up with a troopship and carrying men or

supplies to the beach. We did four or five ship to shore trips each day,

dependant on the cargo. The ships we were serving lay a few miles off the beaches and were in

deep water to avoid enemy mines and fire from inland. Troops were embarked quite

rapidly but stores often took longer, because we had to ensure the balance was

right. Our little LCA was often loaded to it’s maximum and sometimes well

beyond!

Despite our care, on the fifth

trip, we ran into trouble. The seas were

rough and our cargo of stores shifted and, before we could lash them down, a large

wave hit us and the stores lurched forward. Our LCA nose-dived and hit the next

wave. We rapidly filled with tons of water. Above the noise I heard the call to

"abandon craft." She went down in seconds. There was not even time to utter a

quick prayer and, in moments, we were all bobbing about on the surface. As her

crew, we had mastered her little foibles and she had become a home from home.

We floated around on the surface, swallowing seawater, shivering

with cold and in shock but still clinging on to life. Luck, once again, was in

our favour. A passing American tug had observed our plight and moved in to

retrieve us from the sea. We were dried out and given some hot soup before being

returned to our flag ship. We must have been a sorry sight as we clambered back

on board HMS Largs. I had kept a daily diary of events and I kept it in

the only safe and dry place onboard, in the engine room. Alas it had gone down

with the LCA. It was a sad end to a job we all thought well done, but we were

all still alive and able to fight another day!

The following day we were granted two weeks shore leave. We were

all lifted by the news and of course extremely happy. Back at Eastney, we were

given new kit. Back home in Crewe, I met a young girl, who would later became my

wife. I was just beginning to enjoy my leave when a telegram arrived with

instructions to report to Greenock Docks, Glasgow... I was to rejoin the now HMS Empire Battleaxe, graced with the pre-fix HMS following her transfer from

the Merchant Navy to the Royal Navy.

A new task force, designated

"Force X", had been raised for service in the Pacific

theatre, which included the Empire Battleaxe.

D-Day;

Bill's Account

William

Robert Jones, (Bill) CH/X113254. Bill's story of joining up and early

training is recorded below this

Empire Battleaxe

account. If you wish to read it first, click here. William

Robert Jones, (Bill) CH/X113254. Bill's story of joining up and early

training is recorded below this

Empire Battleaxe

account. If you wish to read it first, click here.

Of D-Day morning on board the

Empire Battleaxe,

Bill

recalls, "Our first sight on coming up on deck in the grey dawn of ‘D’ Day

was a Norwegian destroyer just to the east of us. It was breaking in two

amidships and

sinking... the result of a torpedo attack. It was a shocking sight so early in

the day.

Our Landing Craft Obstacle

Clearing Unit, LCOCU, was lowered from the Empire Battleaxe

and we were soon in the water, forming up to proceed to the

our designated beach on the Normandy coast. We were to be the second wave of LCAs

landing troops with a line of 'swimming tanks' between us and the first wave.

The tanks sat very low in the water and

were not easy to see.

We heard the whooshing noise of shell salvoes passing over us from the fifteen inch guns of

HMS Ramillies or Warspite.

The shells were destined for the German defences on and behind the Normandy

coastline. There was also the sound of heavy German guns firing from the east. We heard the whooshing noise of shell salvoes passing over us from the fifteen inch guns of

HMS Ramillies or Warspite.

The shells were destined for the German defences on and behind the Normandy

coastline. There was also the sound of heavy German guns firing from the east.

The

most prominent feature on our part of the coast was a stark line of three story buildings just back from the shoreline, perhaps boarding

houses at the seaside resort of La Breche. The rough seas and

manoeuvring landing craft made our task of

putting divers down to clear obstacles almost impossible. One of our engines

failed when a rope wrapped around our port propeller, which we could not free.

A line of Landing Craft Medium (LCMs) came in. They were next up

in size to the British LCA. They looked so determined to reach the beach, as they made their way past

exploding mines with their front ramps in the air. Regardless, they came on

relentlessly. Many of the slightly larger craft were flying barrage balloons as

protection against low flying enemy planes. A line of Landing Craft Medium (LCMs) came in. They were next up

in size to the British LCA. They looked so determined to reach the beach, as they made their way past

exploding mines with their front ramps in the air. Regardless, they came on

relentlessly. Many of the slightly larger craft were flying barrage balloons as

protection against low flying enemy planes.

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' which shows the

disposition of the Empire Battleaxe and her LCAs].

It was vital

that access to the beach was not impeded by disabled landing craft and it was

our task to get

them out of the beach area and into deep water. We found one abandoned LCA not far off the

shore and drew alongside to attach a line. When we were in deep water, we left

it with an explosive charge on board to dispose of it. We were working in a

dangerous environment with innocuous small splashes in the sea where enemy

bullets hit.

When a gap between the waves of

incoming landing craft appeared, we resumed our primary job of clearing

obstacles. However, the absence of other targets during these periods

concentrated German mortar fire on our position. We were lucky to survive when a

mortar shell fell on the position we had just vacated a few seconds before. Had our craft been hit,

its working stock of explosives

and detonators would have totally destroyed it.

Despite our protests, we were

hailed several times by destroyers to take people ashore. In such situations

seniority and rank matter, so we acted as a ferry to

the shore when required.

During the morning, one particular

house on the foreshore caused a lot of problems. It was later reported to be

well reinforced with concrete and provided the Germans with a well positioned

gun emplacement. A destroyer moved into range and its main armament demolished

the house with its first salvo. Great shooting. The equipment of our diving team

included a radio, so we tuned

in to the BBC one o’clock news. We learned that Churchill had to be

restrained from visiting the beaches, which raised a hearty laugh.

Shortly after this, I heard an

ominous clang and found myself sinking down in my little compartment with blood

running down either side of my neck and down my oilskins across my chest. A lump

of shrapnel had hit the rear of my steel helmet and my head. Paralysed but

conscious, I was dragged out into the well of the boat and replaced by one of the

deck hands. A large wound dressing was put on

the back of my head by our diving friends. One was measuring my very slow pulse and

I heard another say, "Oh don’t say he’s dying."

A nearby destroyer lowered a stretcher into our boat and I was

soon strapped in, hoisted up the destroyer’s side onto the deck and into

the sick bay. I was soon stitched up by the sick bay attendant and was later walking

around again. A day or two later, I was transferred to a Landing Ship Tank (LST).

These were the largest of the craft specifically designed to touch down on the

beaches. They were noted for their large bow doors opening before the ramp was

lowered and they accommodated many vehicles and personnel. This LST had discharged

its vehicles and men and was loaded with wounded for the return trip to Blighty.

Many of the casualties desperately needed help but this was

difficult to provide under these severe war conditions. The limited medical staff were fully stretched.

Later in the day, another boat came alongside to transfer more

survivors and up came the crew of my craft! The night before, they were tied up

alongside a destroyer that made an emergency move during the night, resulting in

the loss of our craft. There were many examples of lucky escapes from death or

serious injury. One such was an RAF glider pilot, who showed us something lying

in the centrefold of his wallet. It was a flat piece of shrapnel just over an

inch in diameter that had penetrated his pocket and one side of his wallet. We

arrived in Southampton on Thursday morning. The injured were decanted into

special trains destined for a hospital in Basingstoke.

After x-rays and nearly a week in bed, I was moved

into convalesce in Ledbury, Herefordshire and some two weeks later to

Cardiff for discharge from medical care and transfer to the Naval establishment at Westcliff, Essex, about five miles from my home. I was

still due sick leave and survivors leave, because my boat had been sunk and I

returned home for three

weeks. After about ten days, I received a re-call telegram and on reporting back

to Westcliff was sent on embarkation leave. I later travelled to Greenock

on the Clyde to rejoin our ship, which was now manned by Naval Personnel and therefore became HMS Empire Battleaxe.

The Empire Battleaxe made two or three more trips across to France to

land troops. On one of these trips, a sister ship, SS

Empire Broadsword, was sunk off the coast of France, presumably hitting a mine

whilst at anchor. By the time the bridge had piped, "Royal Marines man your craft

and go to assist," nearly half our craft had

been lowered and were already on their way. One of our craft tied up to the stern of the

Broadsword and the coxswain dashed down to the engine room to check all

were out. He returned to his craft and only just moved away before the ship

went down. I thought this selfless action should have received more commendation. been lowered and were already on their way. One of our craft tied up to the stern of the

Broadsword and the coxswain dashed down to the engine room to check all

were out. He returned to his craft and only just moved away before the ship

went down. I thought this selfless action should have received more commendation.

[Photo; LCA 779 in German hands washed up on a

beach. From the Archives of Calvados (or AD14) under Public-Administrative

Relations Code (CRPA, Articles L. 300-1].

The flotilla only suffered

casualties on D-Day itself. Three were wounded and a stoker was killed by shrapnel entering one side of the

engine compartment and exiting the other side, killing him in the process. The

LCA'S armour plating stopped short of the engine room at the rear of the area occupied by the troops."

Landing Craft Losses &

Replacements

Official records show the one

fatality was Royal Marine, Gerald Pike. He was killed in action on June 6th, 1944 and buried in France. LCAs in the flotilla on June 5th comprised 429, 496, 524, 584, 611, 653, 770,

778, 779, 780, 781, 792, 840, 898, 1215, 1251, 1252 and 1338, total 18 craft.

Those listed on June 19th comprised 496, 524, 611, 770,

778, 779, 780, 781, 792, 898, 1215, 1251, 1252, 1338, with replacements 760,

987, 1392 and 1393 a total of 19 craft. From the June 5th list 429, 653 and 840

are recorded as war losses.

Later updated lists of war losses comprised 496, 584, 611, 779, 780, 792, 1215, 1251,

1252 and 1338, all in Normandy. It can reasonably be assumed that they were either

D-Day losses, the

details of which had not filtered back by June 19th, or they were

casualties of the great storm of June 19-22nd.

Of the 22 craft associated with Battleaxe over the period of the

Normandy campaign, 13 craft ‘went missing’.

Force X -

The Pacific

Some

of the surviving ships from the Normandy landings were

formed into a new force, codenamed Force X. It comprised seven ships headed

by communications vessel, HMS Lothian, with the Admiral on board. The

other ships were HMS Glenearn, Clan Lamont, Empire Arquebus, Empire Spearhead, Empire Mace and

Empire Battleaxe. We were to assist the American fleet in the South West

Pacific against the Japanese. Some

of the surviving ships from the Normandy landings were

formed into a new force, codenamed Force X. It comprised seven ships headed

by communications vessel, HMS Lothian, with the Admiral on board. The

other ships were HMS Glenearn, Clan Lamont, Empire Arquebus, Empire Spearhead, Empire Mace and

Empire Battleaxe. We were to assist the American fleet in the South West

Pacific against the Japanese.

We left Greenock for New York on

the 3rd of August 1944 and stayed there from the14th to

18th, Charleston 21st to 22nd, Colon 27th to 28th and then through the

Panama Canal. The landing craft on the lower davits made their own way

through the locks. We stopped at Balboa from the 28th to 29th and, once in the Pacific Ocean, we

called at Bora Bora and Papeete in the French Society Islands from the13th to 17th

Sept and then Suva in Fiji.

The ships of X Force

then split up.

Empire

Battleaxe called at Espiritu Santos from 25th Sept to 3rd October, Finschafen, Papua New Guinea,( PNG))

7th to 10th October, Manus Isle, Admiralty Islands, 11th to 13th, Milne Bay (PNG)

and then down to French New Caledonia, arriving there on 20th October. In the

area around Noumea, we spent just over four weeks between the mainland and the

string of beautiful unoccupied islands and a reef. The area was known as St

Vincents Bay.

We practised with

American troops, who, unlike the British, embarked their fully armed troops only when

their LCAs were in the water. Scrambling nets were lowered down the side of their mother

ship and the US troops lowered themselves to the landing craft, timing their

final jump to the rise and fall of the LCA beside the more stable larger ship.

After leaving

New Caledonia on the 21st November, 1944, we arrived off Bougainville on the

25th, where we spent 6 or 7 weeks in Empress Augusta Bay, not far from an active volcano discharging

a plume of smoke. We could see no villages or towns and lived almost entirely on the ship, since the majority of

the island was occupied by the Japanese.

We spent Christmas 1944

there and received food parcels from Australia. The strategy was for the

Americans to invade, establish a beachhead and sufficient land to prepare an

airstrip and then move on to leave the A ustralians to clear the Japanese.

This approach allowed the Americans to concentrate on the main task of

capturing the Philippines and then onward towards

Japan. ustralians to clear the Japanese.

This approach allowed the Americans to concentrate on the main task of

capturing the Philippines and then onward towards

Japan.

[Photo; Members of 537 Flotilla on board HMS

Empire Battleaxe with Sam on the extreme right and Bill third from the left.

The rear row are sitting on one of our LCA’s hoisted up on its davits. Note

the lifeline to the left also the stern kedge and engine compartment

ventilators].

At Bougainville, we were working with the Americans as usual but Sam’s craft

was one of two assigned to the Australian Army to move men and supplies

up the River Ouite. Obstacles and debris flowed down the River making the trip hazardous. The countryside

was, however, beautiful and the wildlife

abundant. The Aussie troops had a good sense of humour

and were courageous without frills. The Australian Commanding Officer expressed appreciation

and commended the

endeavours of the crews of the two landing craft. However, many of our men would have

preferred deployment in support of the Australians,

including their landings in Borneo, where their skills would have been better

utilised.

We took anti-malaria tablets each day but, despite this,

one coxswain caught the disease, while the majority of us suffered the discomfort of

'prickly heat'. Some developed a more serious skin problem causing small watery blisters, which burst to form scabby sores.

However, in the way of compensation, the abundance and variety of sea life was

amazing. We saw flying fish, porpoises, a large swordfish and many other exotic species we could not identify.

Empire Battleaxe left Bougainville on the 14th January,

1945, anchored in Milne Bay from the 16th to 27th, Oro Bay 28 to 30th arriving at

Hollandia on the 2nd February, the then capital of Dutch New Guinea, now Jayapura in Indonesia. On entering Hollandia Harbour, we saw the

largest gathering of ships, including warships, since the invasion fleet we'd

seen in Portsmouth just before the Normandy Landings. As part of a large convoy

we steamed towards the Philippines with a number of medium sized landing craft under tow

because they were not designed for long ocean voyages. The journey took 3 weeks

at the resultant reduced speed of 5 or 6 knots.

The ship’s crew was closed up to action stations at dawn and

dusk each day, the most likely times for an enemy attack. The guns of the Empire Battleaxe were augmented by marines

with strip Lewis machine guns on the port and starboard bow and port and

starboard stern. The marines wore steel helmets and, in some cases, naval

ante-flash gear but felt pretty exposed

standing on the open deck. The ship’s crew was closed up to action stations at dawn and

dusk each day, the most likely times for an enemy attack. The guns of the Empire Battleaxe were augmented by marines

with strip Lewis machine guns on the port and starboard bow and port and

starboard stern. The marines wore steel helmets and, in some cases, naval

ante-flash gear but felt pretty exposed

standing on the open deck.

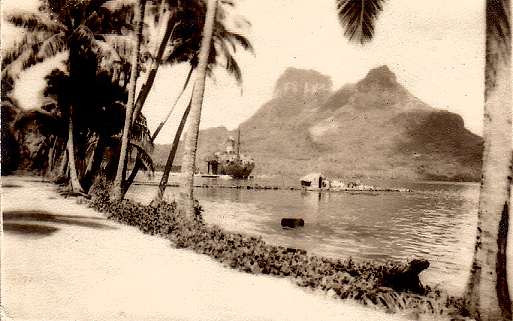

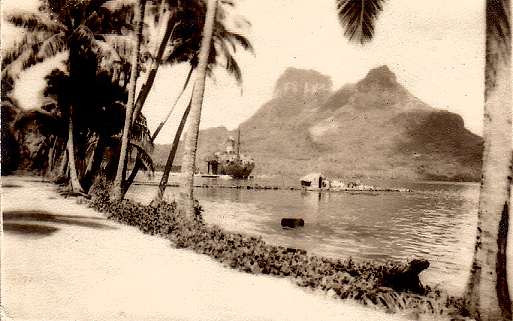

[Photo;

HMS Empire Battleaxe

in the Society Islands, probably Papeet].

The strip Lewis machine gun was based on a water cooled

machine gun of First World War vintage but without the water cooling. It had a

circular ammunition pan on top with a capacity of just under fifty rounds of

0.303. There was an alternative pan holding just under one hundred rounds.

Perhaps the rapid fire from twelve marines would protect the ship!

During

this trip, Bill had a rash of small skin blisters and slept on the upper deck, hoping

the cooler air would aid

recovery. The sick bay medics applied starch poultices to his right torso

and right arm and then removed them to apply gentian

violet. It was the patient's responsibility to wash the sick bay bed sheets,

usually heavily stained by the gentian violet. Bill’s twentieth birthday was

celebrated on this trip.

When we arrived at Subic Bay just off Manila, gun fire could be

heard as the Americans battled to recapture the Capital. The Empire Battleaxe

was soon heading north to the Lingayen Gulf on the West Coast of Northern

Luzon, where we stayed from the18th to the 20th of February, 1945. The ship anchored and the landing craft were lowered. Soon the

American troops were on their way. Bill’s craft was, on this occasion, leading

the flotilla. They negotiated a small entrance to a lagoon giving access to the landing beach. As they entered the

inner water, there was an unexpected strong sideways current that needed both rudder and engines to offset. Great craft... they headed the right way and made a

completely unopposed landing.

Empire Battleaxe started the long homeward journey with

American ex prisoners of war from the Philippines. Their condition was not

great. We briefly called into Hollandia, Milne Bay and then south, leaving Papua New Guinea and down the east coast of

Australia, where we experienced one of the severest storms of our trip. It was

necessary to constantly patrol around the ship to check that the craft did not

move on their davits. Each patrol comprised a coxswain and two assistants. It

was an unforgettable, hazardous experience clambering from the ships side onto

each craft to thoroughly check and adjust the securing

cables.

On the 19th March, 1945, the ship entered Sydney Harbour. Despite everything the Empire Battleaxe had been through, Bill

overheard a ferry passenger comment to her companion, "what a scruffy ship." Whilst we were around the

islands, the crew had repainted the ship from grey, white and blue to various

shades of green and brown to make the ship less noticeable when anchored against

the background of the jungle. On the 19th March, 1945, the ship entered Sydney Harbour. Despite everything the Empire Battleaxe had been through, Bill

overheard a ferry passenger comment to her companion, "what a scruffy ship." Whilst we were around the

islands, the crew had repainted the ship from grey, white and blue to various

shades of green and brown to make the ship less noticeable when anchored against

the background of the jungle.

[Photo; A stern view of HMS Empire Battleaxe taking on fuel and water

in the Society Islands probably Bora Bora].

The crew were granted four days

leave with the choice of the City, the seaside or the country. Sam and friend,

Norman Taylor, opted for the latter and were taken in hand by Mr & Mrs Doyle,

who lived in Sydney. Their house was in the Blue Mountains, where

it was so peaceful compared to the constant noise of engines and

warfare. The Doyles ran a ballet school together and, whilst Sam and

Norman wisely resisted the temptation to practice the art, they did hold

their own on the dance floor, even wearing their boots! Mr & Mrs Doyle

were a lovely couple, who made them feel very welcome and arranged distractions

such as rabbit

shooting, visits to local breweries and underground caverns beneath the mountains.

Bill, on the other hand, was soon on a train with a few others to

the country town of Tamworth. He recalls the trams in Sydney were on strike and

taxis were at a premium. Embarrassingly, servicemen were given priority over

civilians. They were met at Tamworth Railway Station and spent a few days

with a Gwen and George Bailey in Brisbane Street, Tamworth. They were very well

looked after and entertained, although fuel for vehicles was in short supply. All

enjoyed the three weeks the Empire Battleaxe was at anchor in Sydney Harbour.

On the 11th April, 1945, Empire

Battleaxe left Sydney on the journey back to Britain, where a refit would be

undertaken at Falmouth, in Cornwall. The crew needed refitting themselves, as their tropical shirts and shorts

were falling apart. During the journey home, the ports of call were much as the

journey out, Fiji (where Sam celebrated his 22nd Birthday), Tahiti,

Panama Canal, New York and home. Just before reaching Bilbao, by the Panama Canal,

news of the cease fire in Europe reached them. On arrival home, everyone went on

leave without realising that they would never

see their ship or landing craft again.

The perceived wisdom amongst the

uninformed was that all

Combined Operations personnel were due to leave Britain in October, 1945 for the

invasion of Japan towards the end of the year. Those who served as coxswains became NCOs and attended a special training course at Deal in

Kent. It was here that Sam and Bill learned of the surrender of Japan.

For the record, basic pay was

three shillings per day (15p), with a deduction of one shilling per week for

purposes not understood. To this was added six pence per day for Combined Operations, six

pence per day if in tropical areas and four pence per day if aged twenty and you

elected to have money rather than a ration of rum each day. Corporals were paid

an extra one shilling and sixpence per day.

On return to civilian life, Sam was happy that the war was over

but found the initial adjustment to civilian life difficult. HMS Empire Battleaxe had been his home for

so long and the men with him had become his family. In 1966 he moved to Ramsey in

the Isle of Man and returned to Normandy in June,

2004.

Bill spent a short time in Portsmouth with plans to be a

draughtsman in the Royal Marines. He was discharged, due to such skills being in

short supply in civvy street. He arrived home in late December, 1945 or early

January, 1946 and was back in civilian clothes for his twenty first birthday. He

emigrated with his family to Australia in January,

1966 to live in Doncaster east of Melbourne, Victoria. For

family reasons he became known as Bob Jones.

Joining Up and

Early Training; Sam's Account

Sam's war service started in July, 1941 and

ended when the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. He continues, "I

took part in many hazardous operations, when

families and loved ones back home feared receiving a telegram informing them that a loved one was missing

or dead... a background which I have chosen to play down but which should,

nonetheless, never be forgotten.

At the time of writing, I am 83 years of age and have at last

found the courage to record my account of those terrible times, perhaps laying

some ghosts to rest in the process. I was one of the very lucky ones. I saw

plenty of action and came through unscathed. The Royal Marines taught me many

skills and values that proved their worth throughout my life - to gain and give respect,

self-discipline, seamanship and comradeship. At the time of writing, I am 83 years of age and have at last

found the courage to record my account of those terrible times, perhaps laying

some ghosts to rest in the process. I was one of the very lucky ones. I saw

plenty of action and came through unscathed. The Royal Marines taught me many

skills and values that proved their worth throughout my life - to gain and give respect,

self-discipline, seamanship and comradeship.

[Photo left; Sam Moss].

Not long after my eighteenth birthday I was working on a farm

near Crewe in Cheshire. Like countless thousands before me, I decided to

volunteer at the Royal Navy recruiting office in Stoke on Trent but it was full… yes, full!!! As I left

the building, despondent at the news, a larger than life Royal Marine Sergeant

said, "Come ‘ere son. Do you really want to join the Royal Navy and go to sea?"

Meekly, I answered "yes" and asked if he could help. Half an hour later, I took

the King's Shilling! I was in the Royal Navy and returned home feeling very

pleased with the day's events. On the 1st of October, 1941, I reported to Eastney Barracks, Portsmouth.

On the first morning parade, the drill sergeant screeched his

words of welcome, "I am your mother, your father and the biggest bastard

you are ever likely to meet." Later on, I heard other troops repeating the same

words, so they were probably part of the training manual. Even American troops

were 'welcomed' into the Navy in the same way.

After a brief introduction to the unit, my six weeks basic

training began at 7am on the second morning. It was cold, wet and windy on the

parade ground and many of the lads were half asleep on their feet. That soon

changed as the drill sergeant began barking out his orders... and this was only

the start! Apart from the drilling, we were introduced to every aspect of life in

the Royal Navy and issued with a blanco khaki-green uniform, Number 4, plus all the

webbing that would hold the things we needed to fight and survive in the field.

Our hair was cut to regulation standard and we were introduced

to the pleasures of washing and shaving in ice cold water. No showers, hot or

cold! One day was like another and every morning we, and our equipment, were

inspected in close detail. Everything was required to be

spotless, boots polished and all clothes washed and ironed to a high

standard.

At this time, I wished I'd paid attention as my mother washed

and ironed my clothes. When the drill sergeant arrived on the square, I would

think of my mother and wondered if my efforts would pass muster. He was as hard

as nails but was immaculately kitted out with creases on his uniform that were

sharp enough to slice bread!

The drill sergeant was certainly capable of teaching us

all a lesson or two. Sorting out misfits

in a few weeks was a routine challenge for him, since none of us wanted to run around the

parade ground carrying full kit, while the others returned to barracks for a cup

of tea! Many young lads said they'd never take orders from him but, in the end,

they did to a man! Occasionally, he was almost human but generally he was an ill-tempered man with a foghorn attached to his vocal

chords!

Lee Enfield 303 Rifles with

bayonets were issued at the start of the training but no bullets. Weighing

in at nine pounds,

the rifle was heavy to carry on parade, even with the distraction of marching to

the regimental band. After three weeks training, we were in fighting order and

another fifty pounds of kit was added, which we were sure was the

full kit. However, another thirty seven pounds was added a couple of weeks later, taking the total to ninety

six pounds! Obstacle and assault courses became more difficult and marches

became longer! Physical training, swimming and other physical activities made

every moment of rest and sleep precious and extremely enjoyable.

At the end of November, 1941, our basic training was over and we

were given a short period of leave. I returned home to Crewe to see my

family and friends. Not one man amongst us invited the drill

sergeant to come and stay!

A week later, I began my first tour of duty at Leith Docks,

Edinburgh, on the Firth of Forth. The Firth was heavily

mined against enemy assault and, for the next few weeks, I patrolled a barbed wire

enclosure. The duty roster was twenty four hours on, followed by twenty four

hours off. On a duty day, we worked on a four hour rota. At night,

if something was heard, we would challenge "Who goes there?" More often

than not it was no more threatening than seagulls! These duties were not what I

had signed up for, so I volunteered for the Royal

Marine Commando, then based at Winchester in the south of England.

Royal

Marine Commando

Training at Winchester was

far more challenging. There was again a natural antipathy between the lads and the drill

sergeant. Many of the lads broke under the strain of the arduous training and

unremitting

discipline. The drill instructors had a way of dealing with contempt; those to be disciplined stood facing their fellow marines as they marched

off the parade ground to warm barracks. They were then marched and drilled, sometimes

for several more hours.

Route marches began at 0700 hours, initially twelve miles, then

twenty miles, all in full fighting order with fifty-six pounds of kit and rifle. We

would run for an hour then walk for a mile, covering nine miles each time. We

underwent unarmed combat training and struggled our way over and through the

dreaded assault course. No excuses were accepted. We slept outside in all

conditions regardless of the time of year, using bivouacs made by combining two

ground sheets to form a very small tent. It was not as comfy as it sounds!

All went well for a few weeks, when

I contracted severe tonsillitis on manoeuvres in North Wales. Armed with medication, I was given home leave to rest

and recuperate. I stayed with my family in Crewe but things had changed; my friends

had disappeared, the whole town was quiet... all the young folk had gone! On

return to my battalion after the operation, I was ushered into a small office and

told that I had lost so much training that I was being returned to Eastney.

After all the hard work and angst, I was back to square one!

Combined Operations. This time at Eastney I was better

informed, so I volunteered to go to sea, something I'd always wanted to do. I joined the Royal Marine Combined Operations and found myself in North Wales

for a six week intensive training course. This took place at three different

camps, Llangelyn, Llwynwril and Barmouth. Combined Operations. This time at Eastney I was better

informed, so I volunteered to go to sea, something I'd always wanted to do. I joined the Royal Marine Combined Operations and found myself in North Wales

for a six week intensive training course. This took place at three different

camps, Llangelyn, Llwynwril and Barmouth.

Being an eager recruit, I loved the challenge of learning Morse

code and semaphore (to modest speeds), knots, bends, hitches, splices and the

rules of the sea. Ever present were the drill marches and assault course

training. My training ended in Barmouth, where I gratefully and happily accepted

my Coxswain's Certificate.

When

I returned home on leave for a short time, I departed the camp in marching order

with a full kit bag, rifle and the latest addition to my kit... a hammock. The

total weight was over one hundred pounds. Crewe was a busy major intersection on

the rail network but my appearance drew no attention. The presence of the

Salvation Army at most mainline stations was a welcome sight. The volunteer

women were always ready with a cup of tea, a bun and a big smile and the ladies

in Crewe were amongst the best. What a welcome they gave everyone. On behalf of all service personnel who passed through many a railway

station…..thank you ladies, we were most grateful.

A telegram arrived, instructing me to report to Cromarty Firth on

the north east coast of Scotland. I was to join the infantry landing ship the SS Empire

Battleaxe. She was a fine ship, loaned and leased to Britain by America for

the duration of the war. Little did I know I would serve out the war with her.

She was the biggest ship I had ever seen and my first day aboard was daunting.

Joining Up and

Early Training; Bill's Account

In

the summer of 1942, Bill volunteered for The Royal Marines.

"I was

inspired by a poster showing a marine, rifle held out front, charging up a

beach. The Royal Marines were part of the Royal Navy and they accepted 17 year

olds, whereas you had to be 18 for the army. In

the summer of 1942, Bill volunteered for The Royal Marines.

"I was

inspired by a poster showing a marine, rifle held out front, charging up a

beach. The Royal Marines were part of the Royal Navy and they accepted 17 year

olds, whereas you had to be 18 for the army.

[Photo;

the squad at Lympstone in March 1943. Bill is in the front row 2nd from the

right and in the photo opposite].

After a thorough medical

examination which, in my case, included a visit to a Harley Street specialist, I

was duly accepted for service in the Marines. However, I continued my employment

as a draughtsman in the electrical switchgear drawing office at Crompton Parkinsons in Chelmsford, Essex.

On the 2nd of February, 1943, the day after my eighteenth

birthday, I travelled on a railway warrant to the Royal Marine Barracks at Lympstone in Devonshire.

After being kitted out, I joined Squad 528 under Colour Sergeant Hall, ex

Gallipoli, for six weeks initial training.

Training

This initial training involved the regular use of Blanco khaki

green No.4. on all my webbing equipment (straps, belts etc), ensuring my teeth

were healthy, hair cut according to regulations, washing and shaving in cold

water, being inspected frequently and trotting around the parade ground to the

band first thing in the morning! For the first two weeks our training on the

parade ground was undertaken in drill order with ammunition pouches and a Lee

Enfield rifle. For the second two weeks we were in fighting order with a 56lbs

pack. The last two weeks were in marching order with 96lbs not including the nine pound rifle. Apart

from the parade ground drilling, there were marches that increased in length and

weight carried - initially a seven mile route march, then twelve miles and, by

the end of the 6 week course, twenty miles.

We all learnt how to clean, maintain and fire our rifles and a Bren Gun. I achieved a 'marksman’s' score,

which entitled me to wear a crossed rifles patch on my sleeve. I believe some

additional pay was associated with

this achievement.

At the end of this initial six week period, I was transferred

with the majority of the Squad to the 22nd Battalion based in an area of

Devonshire called Dalditch, between Exmouth and Budleigh Salterton. The camp

comprised Nissen huts in an area of rough moor land. We jogged and marched for

miles over the hills of Devon, sometimes based for 72 hours in a two

man tent formed by combining two ground sheets. The marching and jogging was occasionally interrupted to attack a

mythical enemy. We were ‘C’ Company in the battalion and trying to prove we were

commandos!

Any invasion of enemy occupied Europe would involve a large

scale amphibious assault. It was not surprising therefore that we practised

landings from LCAs (Landing Craft Assault) on Slapton Beach. This beach was on the south coast of Devonshire. Any invasion of enemy occupied Europe would involve a large

scale amphibious assault. It was not surprising therefore that we practised

landings from LCAs (Landing Craft Assault) on Slapton Beach. This beach was on the south coast of Devonshire.

[Photo; Royal Marines landing in strength on

an enemy coast].

From the landing craft we

dashed up the fairly steep shingle beach throwing ourselves down and bringing

our weapons up to the firing position. I was given the Bren Gun, which was a bit

heavier than the Lee Enfield rifle. In operational terms it was half way

between a rifle and a machine gun, perhaps best described as an automatic

rifle.

After the charge up the beach, we shed our gear and weapons and

swam fully clothed with our boots on... not an easy task as illustrated by an

observer's wry comment about the direction I was swimming in... forwards or

backwards. I never did understand the purpose of the exercise but it seemed to

be very important. It may be associated with the fact that this area of coast

was used by the Americans to train for the invasion of Normandy. My experience

of dashing up this beach and attacking the enemy made me think back to the

recruiting poster referred to in the beginning of this story.

At the Dalditch camp chemicals were added to the water supply,

which was a likely cause of the runs or diarrhoea amongst the men. The problem

was recognised by the officers and, consequently, permission to leave the parade

ground was not needed, since time was often of the essence! In the quiet of the night

I'd leap, half clothed, from my bed and dash outside to the toilet blocks

silhouetted against the sky on a nearby hill. They were half open to the

elements. It was often a lonely dash until I found all the seats fully

occupied!

I gained the impression that the 22nd Battalion was a holding

camp for partially trained personnel. Around this time, the planners were

developing combined operations using various types of landing craft and, as part

of this process, it was decided that the crews of the minor landing craft,

designed to put men ashore, should be marines rather than naval sailors... the

theory being that if the craft became disabled, the crew would grab their rifles

and storm ashore with the troops. As a consequence, we spent 2 weeks at the Dartmouth

Naval College in Devonshire for training in the handling of small plywood

landing craft personnel (LCPs) on the beautiful river Dart. An aptitude for handling these boats

resulted in you becoming a coxswain, any

knowledge of engines resulted in you becoming a "stoker" and the remainder became deck hands.

The 20 mile or so return journey from Dartmouth back to Dalditch camp is etched in

my memory since we marched! We came up through the seaside towns of Paignton,

Torquay, Teignmouth and Dawlish to a little place called Starcross on the west

side of the mouth of the river Exe. There was a ferry from Starcross to Exmouth and we were reminded that the last ferry left at

6:00pm. If we did not make it, we'd need to march further up river to get across

at the first bridge. This knowledge focussed our minds and kept us going. The 20 mile or so return journey from Dartmouth back to Dalditch camp is etched in

my memory since we marched! We came up through the seaside towns of Paignton,

Torquay, Teignmouth and Dawlish to a little place called Starcross on the west

side of the mouth of the river Exe. There was a ferry from Starcross to Exmouth and we were reminded that the last ferry left at

6:00pm. If we did not make it, we'd need to march further up river to get across

at the first bridge. This knowledge focussed our minds and kept us going.

As we marched by the coast at Torquay, RAF

personnel lolling around thought we were something to laugh at. We all had our problems! We made the last

ferry at Starcross and were amazed and delighted to find trucks waiting for us

on

the other side to transport us back to the Dalditch camp. We had already marched

over twenty miles, so we'd earned the ride.

We

were moved to the coast of North Wales, spending two

weeks at each of three camps at Llangelynn, Llwyngwril and Barmouth. We were now

learning boat skills, including Morse code to a very modest speed and likewise

semaphore signalling with flags, a range of rope skills, bends, hitches, knots

and splices, the use of the compass for navigation and the rules pertaining to

river and sea voyages. We continued to march and drill, perhaps to show the local

Welsh Guards how it should be done!

Our next move was to South Queensferry on the east coast of

Scotland in the shadow of the famous Forth Bridge, which we sailed under and

marched over. We were now part of the 537 Flotilla, the second to be formed from

the Royal Marines. Flotilla 536 was formed a week or two ahead of us. We became

an eighteen craft Flotilla of LCAs (Landing Craft Assault). This meant eighteen

crews of four, plus others to man the winches etc., a total of just over ninety

marines supported by a small contingent of Naval personnel to repair the boats

and look after the engines.

Towards the end of 1943, we left our shore establishment at South Queensferry

and were temporarily accommodated on the battleship,

Royal Sovereign. This 29,000 ton ship, built 1914-1916, had eight fifteen inch

guns and was anchored nearby while waiting to enter the Royal Navy dry dock at Rosyth. She was due a refit, prior to being loaned to the Russians for the

remainder of the war. During this period, some of our eighteen craft were tied up

by the Royal Sovereign with the remainder accommodated at South Queensferry.

We were now sleeping in our hammocks, strung above the mess deck

tables, where we had our meals. The lower decks were ventilated by noisy fans via

ducting. We became acclimatised to the noise and were more likely to wake up if

the fans stopped for any reason!

Much time was spent carrying out day and night flotilla

exercises, often routine and occasionally memorable. One of the latter arose when

all 18 landing craft were proceeding in line ahead down the Firth of Forth. We found ourselves confronted by

either HMS

Rodney or HMS Nelson... in any event, a sixteen inch gun battle ship.

It sounded off four blasts of its horn meaning, "Get out of my way

I cannot get out of yours." Obeying the Flotilla leader's flag signal, we smartly

executed a turn to starboard, ending up in line abreast heading for the right

hand shore.

One evening, I was in charge of the duty boat... the boat taking

people ashore or back to the ship as required. On leaving South Queensferry for

the last trip back to the Royal Sovereign, a thick fog descended. I set

course on a compass bearing and safely arrived at the ship, feeling pleased and

relieved. It helped to confirm my view that we had become competent seafarers!

Further Reading

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Acknowledgments

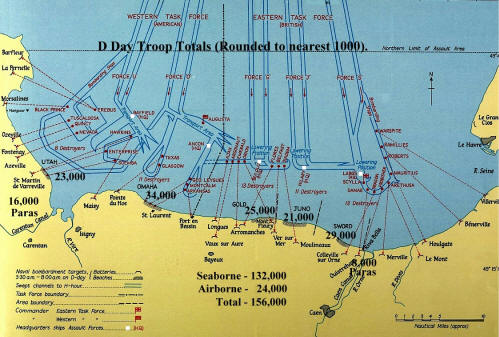

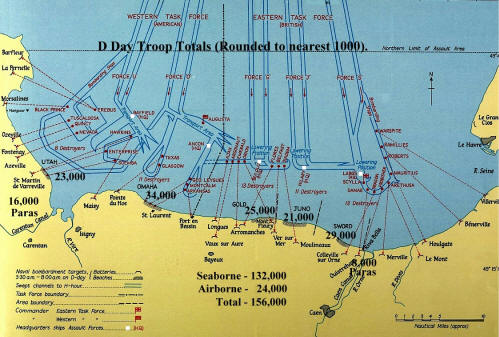

This story of HMS Empire Battleaxe was written by Tony Chapman, historian and archivist of the LST

and Landing Craft Association from Sam and

Bill's personal recollections. It was further edited by Geoff Slee for website presentation,

including the addition of Imperial War Museum photos, location maps, an

Operation Neptune map and an extract from the Admiralty's

"Green List" of craft dispositions just prior to D Day. This story of HMS Empire Battleaxe was written by Tony Chapman, historian and archivist of the LST

and Landing Craft Association from Sam and

Bill's personal recollections. It was further edited by Geoff Slee for website presentation,

including the addition of Imperial War Museum photos, location maps, an

Operation Neptune map and an extract from the Admiralty's

"Green List" of craft dispositions just prior to D Day.

|