The 'Phoenix' Flotilla

Background

LCAs

(Landing Craft Assault), were small, flat-bottomed craft that carried around 35 fully armed troops

and a RN (Combined Operations) crew of 4, from mother ships onto nearby landing beaches, often under heavy enemy fire during the

initial assaults. Their crews comprised a coxswain, two seamen and a

stoker (engine mechanic), plus one officer per group of three craft.

[Photo; Troops leaving an LCA on landing beach.

Imperial War Museum

©

IWM (B5092)].

The craft were powered by two

engines producing a

speed of 9 knots. On reaching their pre-determined landing beaches, they lowered

their ramps and quickly disembarked their troops to minimise the risk from enemy

shells, mortars and gunfire.

Then, as quickly as possible,

they winched

themselves off the beaches using their stern mounted kedge anchors, which were

lowered on the way in, before returning to their mother ships or other troop

carrying ships waiting in line to disembark their human cargoes.

The 10th LCA

Flotilla was one of the first established in 1940. Before the war was over, the

Flotilla

saw several reincarnations, not unlike the mythological Phoenix bird of Greek

legend, hence the sub-title of this page.

Almost all the crews of the

Flotilla were young civilians with little or no previous experience of the sea

or the Royal Navy. To reflect this “civvie” background, the Flotilla badge was

designed as a civilian version of the official badge of “Combined Operations”.

It was much admired and attracted good-natured comment.

10th LCA Flotilla - 1940

Following the evacuation of

the Allied Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk in June of 1940, it was clear that a

future invasion of enemy occupied Europe would require an overwhelming

amphibious assault force to overcome entrenched enemy defences. The army would

need several years to re-equip and re-train as

part of a unified amphibious force under the auspices of the Combined Operations

Command. The Royal Navy's task was no less daunting. They needed to recruit

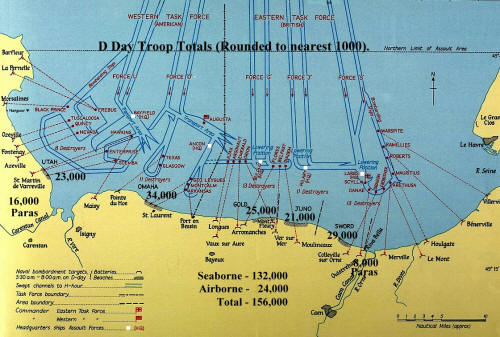

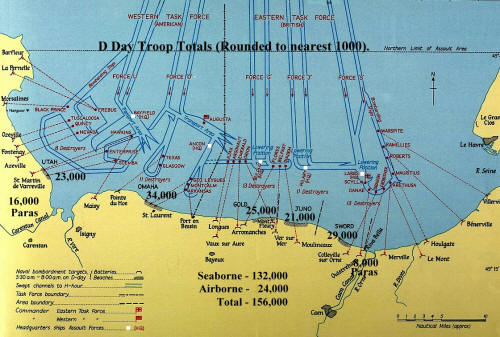

personnel for the thousands of landing craft that, on D Day alone, would transport over 150,000 troops, their equipment and supplies

to the landing beaches. Some basic training in seamanship was provided in

Milford Haven from November 1940, using Yorkshire Cobles (small fishing boats)

with a limited speed of about 4 knots. However, they served their purpose during

training in basic seamanship while the many types of landing craft were designed

and manufactured in sufficient numbers to meet demand.

In

1941, the crews of the 10th LCA

Flotilla reported to the Princess Astrid, a Belgium cross-Channel passenger

ferry which had been converted to an LSI (Landing Ship

Infantry) in Falmouth Dockyard. It had davits for eight LCAs, four each side, an arrangement

not dissimilar to that used for lifeboats on ferries. The Princess Astrid

was destined for Inveraray on Loch Fyne in Scotland, which was the site of the

No 1 Combined Training

Centre, of which HMS Quebec was the naval component.

In

1941, the crews of the 10th LCA

Flotilla reported to the Princess Astrid, a Belgium cross-Channel passenger

ferry which had been converted to an LSI (Landing Ship

Infantry) in Falmouth Dockyard. It had davits for eight LCAs, four each side, an arrangement

not dissimilar to that used for lifeboats on ferries. The Princess Astrid

was destined for Inveraray on Loch Fyne in Scotland, which was the site of the

No 1 Combined Training

Centre, of which HMS Quebec was the naval component.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

In the absence of finished LCAs, single

engine, timber hulled “Eureka” boats from the USA were made available providing

a more appropriate speed of about 10 knots. However, while they were good sea

boats, they were unpopular because of their loud engine noise, difficulty in disembarking

troops onto landing beaches and their vulnerability to

enemy fire in conflict situations.

The design specifications of

the various landing craft were modified as training exercises and operations provided

useful feedback on their performance. Over the years, new versions emerged in

the series Mark 1, Mark 2 etc.. Early in 1942, the “Eurekas” were replaced by LCAs constructed of steel

and for the following six months, the Flotilla carried out training exercises in Scotland

and the south of England. These included seamanship, embarkation and

disembarkation of troops and realistic landings with smoke screens, beach

strafing and the dropping of small bombs courtesy of

516 Squadron RAF.

The true value of all this training became apparent when the Flotilla was

engaged in real operations against the enemy, which tested the crews to the limit and

beyond.

The Dieppe

Raid

On the 3rd July 1942, Chief

of Combined Operations, Lord Louis Mountbatten, briefed the crews on an imminent raid.

It was on

the small French port of Dieppe in north-west France. Codenamed

Operation Jubilee, the plan required the flotilla to

carry troops of the Royal Regiment of Canada from our mother ship to a small

beach adjacent to the village of Puys,

to the north-east of Dieppe, and to collect them from a beach, adjacent to

Dieppe, on completion of the operation.

The operation was to begin

the following morning but unfavourable weather forced a

postponement. A further setback occurred when, at 06.00 hrs on July 7th, four German aircraft attacked

Princess Josephine, Princess Charlotte and Princess Astrid, scoring direct hits on all

three. Remarkably, all the bombs passed straight through the ships before

exploding, causing only minor casualties and limited damage. The troops were

disembarked and the ships returned to Portsmouth for repairs. Against the advice

of General Montgomery that the operation “be off for all time” because

the pre-raid tight security had been compromised, the Chiefs of Staff approved a revised plan to mount the attack in August.

Our

landing was on

the 270 yard long 'Blue Beach', which was liberally spiked with obstacles and

overlooked by high cliffs, on which a number of concrete pillboxes

were strategically placed. Confronted by these conditions, it was vital to

achieve complete surprise lest the assault troops became sitting ducks to the

enemy's fire. Critically,

touch-down at 05.05 hours was 15 minutes late and in the early dawn

light the enemy opened fire long before the troops reached the beach.

Our

landing was on

the 270 yard long 'Blue Beach', which was liberally spiked with obstacles and

overlooked by high cliffs, on which a number of concrete pillboxes

were strategically placed. Confronted by these conditions, it was vital to

achieve complete surprise lest the assault troops became sitting ducks to the

enemy's fire. Critically,

touch-down at 05.05 hours was 15 minutes late and in the early dawn

light the enemy opened fire long before the troops reached the beach.

The LCAs scraped to a halt

several yards from the beach and the bow ramp was lowered to allow the soldiers

to storm ashore. Intense machine gun fire rained down from the cliff as dead and

wounded piled up in the bow of the landing craft. Those who managed to

disembark, struggled in the shallow water and were not immune to the fusillade.

The sea wall was only 40 yards away but not more than fifteen men from the first

wave, reached it. Within a few tragic minutes, Puys beach was a bloody shambles.

The Flotilla withdrew to a

relatively safe distance to await orders. At about 0900 hrs, a motor launch

approached and by loud hailer ordered us to “go immediately to Blue beach

to take off troops.” Under cover of a smoke screen, four craft set off but as

they emerged from it, two of them were immediately hit, one of which sank. When there was no sign of life on Blue beach, the remaining craft

were ordered to “come back.”

Unbeknown to our commanders, Canadian troops had started to surrender at 0830

hrs, when the odds against them were overwhelming and by 0840 hrs, Puys beach was

firmly in German hands. Of the 490 men who landed, 225 were killed and the survivors

became prisoners of war. At about 1030 hrs, all available craft were ordered to

rescue troops from the Dieppe beach. Together with craft from

other flotillas, about 500 men were rescued under intense enemy

fire from mortars and machine guns.

Describing the events of that

day, the official record of the Canadian Army observed “the disaster at Puys beach

was the blackest event of a black day. The Royal Regiment of Canada suffered

such heavy casualties that it had virtually ceased to exist as a unit.” The

Canadian public were outraged by the loss of life and demanded that the

Admiralty should court-martial those responsible, but none was held.

Shockingly, of the Canadians troops carried by the Flotilla to Puys beach

that day, not

one returned. They were either killed or captured and many

of the survivors, unsurprisingly, suffered from shock. The crews of the 10th LCA Flotilla

will always remember, with deep sadness, the loss of so many young Canadian

soldiers, whom they had come to know and respect.

The above account was based

on one written by Alasdair Ferguson, who took part in the raid for

which he was awarded the DSC for his courage. Lessons were learned for future

landings including D-Day, but a very heavy price was paid.

Watch Michael J Moore's

moving musical tribute to the 6000 men who took part in the raid (highly

recommended).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05aoODbtOUw

The 60th LCA Flotilla - 1942/43

Shortly after the Dieppe raid,

the Admiralty created the 60th LCA Flotilla with Lt Alasdair Ferguson as the Flotilla Officer.

Some members of the 10th LCA Flotilla were transferred to it and just two

weeks after Dieppe, the Flotilla joined its mother ship, the SS Duchess of Bedford.

Before being requisitioned for war duties, she was a Canadian Pacific ship of 23,000 tons designed for

the North Atlantic run. In her converted state she had a capacity of 14 LCAs with their crews and troops,

a total of 560 men.

North

Africa - 8th November 1942.

As part of

Operation Torch, not known to us at the time, we

embarked the United States 1st Infantry Division for joint amphibious training

exercises in the River Clyde estuary in

Scotland. Observing the rain falling on Greenock with the barrage balloons

overhead, one wit is said to have remarked: “Why do they not cut the strings and

let the god-dammed place sink!” Clearly the young soldiers were unimpressed with

the weather!

Training over, we sailed from

Liverpool through the Bay of Biscay as part of a huge convoy of ships stretching

from horizon to horizon. With heavy Naval protection, we passed through the

Straits of Gibraltar with the North African coast to our right. Our destination

was a dropping off point about 9 miles off the beach at Arzeu, Algeria. The troops embarked

the LCAs and were lowered into a calm sea. The run into the beach was uneventful

and the landing was unopposed. Several return trips were made with

additional troops and equipment landed. Surprise was complete and the Vichy

French were unable to react.

The Duchess of Bedford

then returned to Liverpool through the Bay of Biscay, where the Flotilla left the

ship for Westcliffe-on-Sea to await further orders.

Sicily -

10th July 1943

Early in March 1943, the

Flotilla rejoined the Duchess of Bedford on the River Clyde. As part of a

convoy, she travelled to Freetown in north-west Africa, across the Equator to

Cape Town, South Africa, arriving there by mid-April. After refuelling and

re-provisioning, she sailed

up the east coast of Africa, through the Red Sea to arrive in Tewfik at the southern end of the Suez Canal.

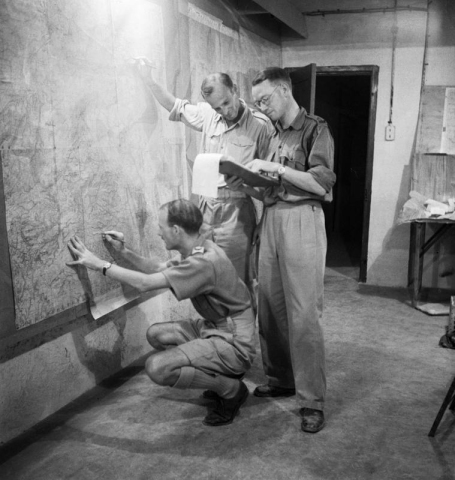

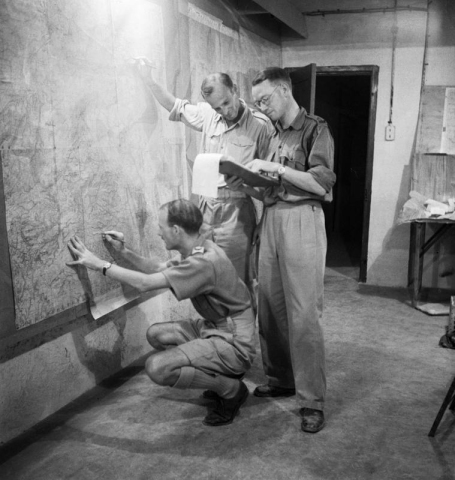

[Photo; Scene in the

underground Operations Room at Malta from where Operation Husky was coordinated. Three British staff officers

plot positions on large wall charts. The Operations Room was located in one of

the caves on Malta as an air raid precaution. © IWM (NA 4094)].

For a month the Flotilla

carried out training exercises in amphibious landings with the crack British

50th Division that had fought in the desert campaign. On completion of this, the

flotilla continued its journey north through the Suez Canal to Mers el Kebir in Algeria in readiness for our

next operation which proved to be Operation Husky, the

invasion of Sicily. We were briefed on our

landing beach at Porto Gerbo, including beach conditions and soon after departed for

Sicily, fully provisioned and loaded, arriving at our disembarkation point about

7 miles offshore on the 10th of July. We transported the 50th Division to the

beach where they encountered some light shelling.

Gliders were deployed to transport British paratroops behind enemy lines, but all

did not go well. With our troops safely delivered to the assault beaches, we

began a search for 47 gliders that had ditched in the sea having been released

early from their towing aircraft. We found some gliders floating serenely on a

calm sea but nothing prepared us for the gruesome sight that confronted us when

we looked inside. There was row upon row of

young British paratroopers, all dead; their necks broken on impact with the water.

No words can describe the

emotions of those who witnessed these horrific scenes. It was no doubt a simple

error that had tragic consequences, made all the more impalpable because the landings

themselves had been comparatively easy.

Reggio, Italy - Operation

Baytown, 3rd September 1943

When the Allies reached the

north of Sicily, there was an immediate need to transport the advancing troops

across the Strait of Messina to Reggio on the "toe" of Italy, a few kilometres

away. To assist with this, the Naval authorities in Cairo ordered part of the

Flotilla, including three LCAs, to Messina in the north-east of the island, the

closest port to the Italian mainland. During the hours of darkness, searchlights were used to guide the craft safely to their

destination and the task was completed without casualties.

Salerno, Italy - Operation

Avalanche, 9th September 1943

Salerno, Italy - Operation

Avalanche, 9th September 1943

Meantime, the Duchess of

Bedford, with the remainder of the LCAs, was lying in Mers el Kebir in Algeria

about 1,500k to the west. As a plan developed to by-pass the German

defensive line by landing troops further north on the west coast of Italy, the Naval authorities in Cairo

reluctantly allowed the Reggio detachment of LCAs to rejoin the main Flotilla.

On the 8th of September, the

35th Division of the United States Army was embarked and the next day the

flotilla departed for the beaches at Salerno. Whilst at sea, we learned that

Italy had surrendered, which caused great jubilation. We expected the Italian forces would not oppose the

landings, but, as we were soon to find out, the Germans had other ideas. Under cover of darkness, the LCAs were lowered into the water nine miles from the beach. To maintain the

element of surprise, there was no bombardment but, as we neared the beach, we

could see German tanks firing at the approaching craft. The Allied ships,

including Warspite, returned with heavy gun-fire.

The Flotilla made several

more trips and although some LCAs were hit, no serious damage resulted. However,

the

Germans deployed glider bombs for the first time with devastating effect. Allied casualties

were so great and unexpected that orders were given to prepare to evacuate the

troops, but in the event this proved unnecessary. During the night, the Duchess of Bedford was targeted for a heavy bombing raid. All hands manned the

twin Oerlikon guns repelling the enemy planes and no damage was inflicted upon

us.

With our job done at Salerno,

The Duchess of Bedford sailed to Malta in time to witness the surrender

of the Italian Fleet. On the way back to the UK, we picked up German prisoners of

war from Mers el Kebir and

Algiers, including Panzer

troops, whose arrogant bearing and discipline was, nonetheless, quite

magnificent to witness. When the Duchess of Bedford arrived in Liverpool, the Flotilla left the ship for

the last time. We had become very fond of her and were sorry to bid her

farewell.

Recollections of L/Coc

Howard Milner 1942/43

I first met the Duchess of

Bedford and the 60th LCA Flotilla in September 1942 in preparations for the

landings on North Africa (Arzeu), a small town close to Oran.

Upon completion, we returned

to the UK where we made preparations for the next landing in the Mediterranean. We

rejoined the Duchess and sailed out into the Atlantic and south

refuelling and re-provisioning at Freetown, Capetown and Aden before proceeding through the Red Sea to Taufiq in the Gulf of Suez. There,

routine maintenance such as painting, together with joint

amphibious training exercises, were undertaken as we prepared for

the assault

on Sicily which, for us, took place on the 10th of July 1943 at Porto Gerbo.

We returned to the UK,

re-provisioned and embarked more troops for Sicily, where the action was drawing

to a close. We disembarked the troops at Augusta and the

Flotilla was then split in two; the smaller part joined up with other splinter

groups to land on mainland Italy at Reggio, on the 3rd of September and the larger part

landed on Salerno, on the 9th. After a couple of

other jobs in the Mediterranean, we returned to the UK once again. On arrival in

Liverpool, our LCAs were taken off the ship and tied up to harbour bollards. This was

to be the last time I saw the Flotilla since, after a short shore leave, I

reported to Hayling Island for training on LCM/LCT craft (myself and Fred Harris).

We were also trained to

coxswain and crew Thames barges, which turned out to be the real purpose of the training. This

training was given by civilian Thames Lightermen who taught a crew of three, one

stoker and two seamen, how to handle these monsters. Someone must have thought

this was a job for the Navy! After training, Fred Harris, who was not a fit

person, was returned to Chatham barracks and invalided out of the service.

I and two other crew members

took the barge to Portsmouth, where we were loaded to the gunnels with ammo and

given two other “engineless” fully loaded ammunition barges to take in tow. For

security reasons, these vessels were given no identification. We were given an

escort of three Motor Launches to help us navigate our way across the English

Channel.

We sailed on the late tide on

5th June, my birthday, consuming double shots of rum to numb the pain. I anchored my barge

off the beach and reported to the beach master. The barges were tied to a

central mooring point formed by a breaker of sunken ships off Juno beach. I

worked for the beach party for two days – then returned to the UK in an American LCI. At Portsmouth, I joined the crew of an LCT, loading

it with tanks and supplies

and returned to Juno beach.

On return to the UK, I was

drafted back to RN Portsmouth and took leave for a couple of weeks. I then

joined HMS Formidable as part of the ship’s company regulating staff. The

ship carried RN personnel, aircraft and supplies as

well as injured Aussie service personnel back to Australia for care and demob.

We returned to the UK for a

further load and, on arrival in Australia, I worked as shore

patrol in Sydney as assistant to the RPO. In this job, I learnt to ride a

motorbike and did a stint as a despatch rider. I was given an old Harley

Davidson to ride and have you ever seen a matelot on a motorbike!

I returned to the UK in

Formidable in 1946 and back to Portsmouth for demob.

524 LCA Flotilla - 1943-44

In December 1943, the name of

the Flotilla was changed once more from the 60th LCA Flotilla to the 524 LCA

Flotilla. Its new shore-based establishment was HMS Cricket in Burseldon, Hampshire.

In December 1943, the name of

the Flotilla was changed once more from the 60th LCA Flotilla to the 524 LCA

Flotilla. Its new shore-based establishment was HMS Cricket in Burseldon, Hampshire.

[Photo;

HMS Empire Arquebus, Landing Ship Infantry (Large), 29 July, 1944 at Greenock.

© IWM (A 25026)].

The Flotilla undertook

training exercises in the Solent and local waters but, in view of our past

operational experience, it added little to what we knew already.

However, it was better than doing nothing, since inactivity and boredom had an

adverse effect on discipline and morale. The poorly insulated Nissen huts we lived in were very cold

especially when the log burning stove ran

low on fuel during the nights. There was, however, no shortage of logs in this

wooded area.

One day, as a change from the

normal routine, the Flotilla invited the workers who built our craft, to join us

on a short trip out to sea. They thoroughly enjoyed seeing the product of their

labours in action. We repeated the exercise with the Wrens who ferried us back

and forth to our craft, which were moored a short distance from the bank of the

River Hambel. After such outings and training exercises, we often visited The Swan for a

few “bevvies” therein. Very welcome indeed! When a night out in Winchester was

called for, we would hitch rides from passing lorries.

SS Empire Arquebus

In early April 1944, much to

our relief, the Flotilla transferred to the Empire Arquebus. She was

built in Wilmington, California and pre-war had been a Red Ensign ship managed

by Donaldson Brothers. She was 4,800 tons (net) and was fitted out to carry 20 landing craft -

17 LCAs and 3 LCMs, the

latter being stowed on the upper deck and the former hung on davits.

The Flotilla increased to 10 craft with the arrival of a contingent of

Royal Marines, For the next two months, numerous training exercises were carried out

in different locations along the South coast.

Operations Neptune & Overlord - 6th

June 1944

Although everyone knew an

invasion was likely in the weeks ahead, only a select few senior military

personnel and politicians knew the full details. They were on the 'BIGOT' list,

an acronym derived from British Invasion of German Occupied

Territory, a designation that

remained unchanged even after the USA entered the war. However, no one was in

any doubt that our flotilla would be involved when the time came. We could see

troops and vehicles assembling along roads for countless miles in the surrounding

Hampshire countryside as they prepared for embarkation.

At the end of May, a

top-secret meeting was held in the Civic Centre, Southampton. Security

precautions were very tight to avoid the enemy gaining any prior knowledge of

the planned invasion. I was instructed to carry my identity card and

furthermore, I was to be accompanied by another officer who could vouch for my

identity. At the entrance to the Civic Centre, I was searched and had my

identity card examined twice. I was shown into the hall, which was filling up

with officers from the Royal Navy, the Army, the Air Force and other allied

fighting forces. Admirals, Generals, Captains, Colonels and other lesser beings,

were seated facing a large stage.

At the end of May, a

top-secret meeting was held in the Civic Centre, Southampton. Security

precautions were very tight to avoid the enemy gaining any prior knowledge of

the planned invasion. I was instructed to carry my identity card and

furthermore, I was to be accompanied by another officer who could vouch for my

identity. At the entrance to the Civic Centre, I was searched and had my

identity card examined twice. I was shown into the hall, which was filling up

with officers from the Royal Navy, the Army, the Air Force and other allied

fighting forces. Admirals, Generals, Captains, Colonels and other lesser beings,

were seated facing a large stage.

On the stroke of ten, Wynford

Vaughan-Thomas of the BBC stood up and advanced to the lectern. He spoke briefly

and with great gravitas. He said “Ladies and gentlemen, you are about to be told

the greatest secret of the war. You will be told where and when the invasion

will take place. I cannot emphasise strongly enough the need for total

security.” With a dramatic gesture, he pointed to a doorway from which General

Montgomery strode purposely on to the stage and advanced to the lectern. In his

clipped military voice he began to speak. We were all ears and we leant forward

to catch every word but, to the astonishment of all, he was competing against an

earnest discussion between two cleaning ladies, who emerged with pails and mops,

quite oblivious to the proceedings going on around them. They strolled through

the hall talking to one another, “Well, you know what Bert is like, he always

wants his own way just like my Bill. Men are all the same!” Everybody burst into

laughter. Monty looked furious! After a while, he started again but titters

still continued. Sometimes reality is indeed stranger than fiction!

In essence, General Bernard

Montgomery announced the date and destinations of the amphibious stage of the invasion, codenamed Neptune. Specific maps, charts

and photographs were issued for each flotilla together with detailed assembly

and convoy instructions according to a strict timetable.

The 524 Flotilla was given

the task of landing the 1st Battalion Hampshire Regiment of the 231 Brigade,

50th Division. They were a very experienced Division with whom we had worked

before. Our destination was Le Hamel near Arromanches. The original date of the

landing was the 4th of June but there was a delay of 24 hours due to force

5/6 winds from the west/south-west. Once the details of the landings had been

disseminated to those taking part in the invasion, no one was allowed ashore.

On June 5, a gap in the bad

weather was identified and after careful consideration, Eisenhower issued

orders for the invasion to go ahead. By this time a massive fleet of ships had

gathered in the Solent, the largest ever seen before or since. The anchorage

stretched as far as the eye could see. From our assembly point, the ships

weighed anchor at about 1830 on 5th June, soon passing by the Needles before

turning south through the marked channel, which had been cleared of mines. The

Fleet was an awe-inspiring sight, quite impossible to comprehend in its vastness

and complexity.

At 0530 on June the 6th, the

Empire Arquebus dropped anchor in its marked spot some seven miles off Gold

beach. The Flotilla was lowered into the choppy water, formed up in two lines

and made for the beach. Battleships, cruisers and destroyers fired their guns,

aircraft dropped bombs and smaller craft fired their rocket salvos, all designed

to destroy or disable enemy defensive positions on and behind the landing

beaches. The landing craft, carrying troops and equipment ashore, stretched as far

as the eye could see. Such was the spectacle that fear and apprehension about

what would unfold in the hours ahead, gave way to sheer amazement.

As we neared the beach, the

Flotilla craft took up their landing formation of “line abeam.” Each craft

weaved its way past the fixed beach defences with shells attached pointing

towards the approaching craft. Machine gun bullets could be heard striking the

sides of the LCAs. The German defenders were still very active despite the

intensive bombardment they had been subjected to. On the order “down ramp”, the

troops we carried ducked and dived their way off the craft and onto the beach.

We then headed out again to a predetermined point where we would

receive fresh orders.

On the way, Alasdair spotted a diver in the water. He had been engaged in

removing mines from the beach obstacles. He was lifted on board and to

everyone's amazement he turned out to be a classmate of Alasdair's!

For the rest of the day, we

were kept busy ferrying troops from the off-lying troop-carrying ships to the

beach. Many LCAs had been sunk or disabled so our services were in high demand.

As night fell, we secured the landing craft to the stern of a motor launch.

During the night the wind increased enough to make us wonder if the next day's

landings would be in jeopardy. Fortunately, by dawn the wind had dropped

but, despite this, many craft had been driven ashore. We managed to tow off some

of our LCAs so that they could resume the ferrying of troops but, sadly, by then

my LCA lay on the seabed.

When Ian and I visited the

Arromanches area, we witnessed the arrival of the first block-ships to create the

outer breakwater of the Mulberry Harbour and the placement of the enormous

concrete caissons as they were maneuvred into position and then sunk. By then,

the work of the minor landing craft, including the LCAs, was over; our task was

done. The Flotilla returned to Southampton on our mother ship and was then sent to Brighton

under its own power, where it was disbanded. Those who took part in the largest

amphibious invasion force in history can look back with pride to the part they played in the

eventual defeat and downfall of Hitler and his hated Nazi regime. I hope that this brief record will bring back

memories to those who were there and preserve the memory for younger generations

to appreciate.

For a more detailed account

of the LCAs and LCMs in the 524 Flotilla on D Day visit

this page.

Roll of Honour

A/B Stanley Bayliss, killed in action

1944 /

Sea. T. Brown, killed in action

1942 /

A/B David Hynd, killed in action

1942 /

Lt. Hugh Mace, killed in action

1942 /

O/S William Martin, killed in action

1942 /

A/B Philip Peake, died in POW camp

1942 /

Sto. W Walker, died in POW camp

1942 /

Sto. QA. A Warren, killed in action

1942

Decorations

and Awards

A/B J Allen, DSM

/ L/S B Anderson, DSM / L/S A Ferguson, DSC and Bar.

MID / A/B R Gale, DSM / S/Lt F Grant, MID / A/B S Harris, MID /

Lt RM R Hill, DSC / Lt RNVR W Hewitt, DSC / S/Lt L Lowry RNVR, MID / A/B J Msckensie, MID

/ RM M Mellett, MID / Lt RNVR D Murray, DSC / PO J Roberts, MID

/

Eng D Shaverin, MID / Lt RNVR P

Snow, MID / Sto E Wheeldon , MID / A/B E White, MID.

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which can be

purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose search banner

checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in or copy and

paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more information.

Acknowledgments

The content of this webpage,

unless otherwise stated, is based upon material supplied by Alasdair Ferguson

and Royal Marine HR ‘Lofty’ Whitting. It was transcribed by Tony Chapman of the

LST and Landing Craft Association and edited by Geoff Slee for website

presentation, including the addition of photographs and maps. This was the last of many web pages about landing craft provided

by Tony over 10 years until his untimely death on June 6th, 2013. His

contribution to the recording of the history of landing craft was enormous. His

friendship and great knowledge of the subject, are sorely missed.