|

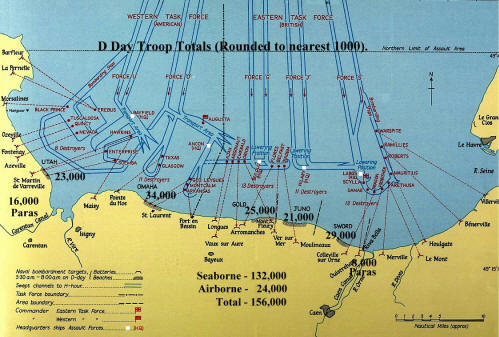

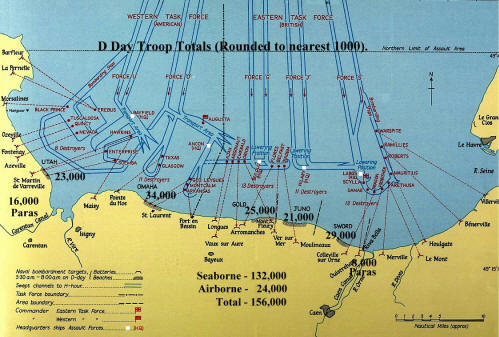

D-Day Landing Craft

and Normandy Beaches.

Utah & Omaha, Gold, Juno &

Sword.

A selection of personal testimonies that convey a

sense of the hazards, challenges, death and destruction witnessed by the crews of landing craft on D-Day, June 6, 1944. A selection of personal testimonies that convey a

sense of the hazards, challenges, death and destruction witnessed by the crews of landing craft on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

[Map courtesy of Google Earth].

Background

Landing directly onto

unimproved beaches defended by the enemy was the only viable option open to the

Allies, because all useable ports and harbours were in

enemy hands. That was true in North Africa, Sicily and Italy but Normandy was

unique in human history because of its vast scale.

Many valuable lessons were learned from the ill-fated

amphibious assault on

Dieppe

of August 1942, which were incorporated into the planning for the Normandy

landings. These included;

1) the need for

reliable intelligence on the strength and disposition of the

defending forces and the topography on and around the

landing beaches. Lt Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Willmott,

RN, who had undertaken beach reconnaissance trials in the

Mediterranean, was recalled to the UK in the summer of 1942

to set up training programmes for the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties

(COPPs). Beach reconnaissance became an integral part

of

the planning process for the

invasion of North Africa

in early November 1942 and in all future major landings.

2) consideration of the

supporting role of vessels at sea produced numerous landing

craft adaptations such as: Landing Craft Gun LCG, described by the BBC on

D-Day as 'mini battleships' with their 4.7 inch guns and

other armaments, operating inshore; Landing

Craft Flack, LCF, to provide anti-aircraft cover

over the landing area;

Landing Craft

Tank (Rocket), LCT (R) for the initial bombardment of

the beaches in advance

of troops landing and Landing Craft Assault (Hedgerow), LCA

(HR) that could lob volleys of spigot bombs onto the beach

area to detonate hidden enemy mines.

3) the need for troop commanders

afloat to be aware of the on-going progress of the invading

force was essential for well considered and justifiable

decisions on, for example, the commitment of reserves or a

timely and well organised strategic withdrawal.

4) the need

for landing craft

to be armoured against small arms fire was now considered an

imperative

to reduce casualties on the approaches to the landing

beaches.

The Approaches

At dawn, on the morning of D-Day, the 6th of June 1944, the greatest armada ever assembled stood ready

for action a few miles off the landing beaches of Normandy. Their presence, at

this pivotal point in history, was the culmination of four years of training in

the use of a myriad of landing craft, involving hundreds of thousands of personnel

from the three services.

For many of the craft that summer morning, the journey across the

English Channel had been

long and arduous. Many of the first wave LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) had set out

during the early morning of June 5th, laden with troops and tanks. Their journey

had taken around eighteen hours and for the landing craft officers and crew

these were sleepless hours, as they focussed on maintaining their position in the

convoy and scanned the sky and sea for

German activity.

For many of the Royal Navy

landing craft crews serving under the Combined Operations Command, D-Day would

be their first action, while seasoned veterans of the many landings in the

Mediterranean during 1943 were better able to prepare themselves for what lay

ahead.

The

rough sea conditions caused violent seasickness amongst the troops and gaining the

shore to face the

enemy was mitigated by the thought of ridding themselves of the nausea. The American built, British manned Mk5 LCT 2226 making for Utah beach broke down and was forced to return

to the UK for repairs. The

men of the US 4th Infantry Division aboard 2226 were in a state of severe distress,

which crew member, George Cooper described, "the craft was awash with vomit."

All landing craft were, by design, flat bottomed

with a square front end for

close inshore work and beach landings. They were more difficult to handle and

more susceptible to the motion of the sea and wind than conventional craft, even in calm

water. In the run-up to D-Day, 48 American built Mk5 LCTs, serving with the Royal

Navy under lend-lease, had been converted to LCT(A) and LCT(HE) - 'Armoured' and

'High Explosive' respectively. The LCT(A)s in particular were very vulnerable in

rough seas, because their centre of gravity had been raised when ramps and

elevated platforms were installed to allow the tanks to fire over the bows, forcing

the defenders to keep their heads down. However, in this configuration they were

more prone to turning over in heavy seas.

Gold Beach

(25,000 Troops)

Making her way to Gold beach that morning as part of the 109th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla was LCT

(A) 2039. The craft were carrying Centaur and Sherman tanks of the 1st Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group. They were part of the 'first assault' on King sector of Gold beach, to the west of La Riviere,

in support of the 69th Infantry

Brigade of the British 50th Division. Sadly 2039 was swamped and turned turtle

in the early morning hours when some 20 miles off the

beaches. Two crew members, Able Seamen Illingworth and Donnelly were

lost. Making her way to Gold beach that morning as part of the 109th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla was LCT

(A) 2039. The craft were carrying Centaur and Sherman tanks of the 1st Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group. They were part of the 'first assault' on King sector of Gold beach, to the west of La Riviere,

in support of the 69th Infantry

Brigade of the British 50th Division. Sadly 2039 was swamped and turned turtle

in the early morning hours when some 20 miles off the

beaches. Two crew members, Able Seamen Illingworth and Donnelly were

lost.

[Photo; Troops from 50th Division coming ashore from LSI(L)s,

Gold area, 6 June 1944. © IWM].

Initially the survivors were picked up by a control craft

and later transferred to the

Canadian troopship Prince Henry en route to England, having disembarked

her cargo on Juno beach. 2039 remained afloat and was sunk by the Royal Navy, as

the upturned hull was a hazard to shipping.

As the British 50th Division closed on Gold beach,

the 231st Infantry Brigade and their support

units were lowered from the

troopships Empire Arquebus, Empire Crossbow, Empire Spearhead and Glenroy, their destination the Jig Red/Jig Green sectors at Le Hamel.

On their left (to the eastward), on to the King Red/King Green sectors at Ver sur Mer, the men of

the 69th infantry Brigade were lowered from the

troopships Empire Halberd, Empire Mace, Empire Lance and Empire Rapier.

In support on Gold beach were the men and craft of 'D' LCT Squadron.

Numerous craft from its five flotillas were hit and in difficulty, including the loss of Mk4 LCT's 809 and 886 of the 28th Flotilla. LCT 810 lost Able Seaman John Tilley.

Sub Lieutenant Victor Bellars

was in command of LCT 896. He recalls; "With a spigot LCA(HR) in tow, a landing craft equipped with up to 24 mortars,

we approached our designated landing area – Gold Beach, King, Red Sector. It was

a wet and windy night and the LCA crew had a most uncomfortable time. About a

thousand yards off the beach, the LCA slipped the tow and proceeded independently,

at some stage firing her spigots on to the beach near the German beach defences.

This allowed me to more safely beach in that area. Sub Lieutenant Victor Bellars

was in command of LCT 896. He recalls; "With a spigot LCA(HR) in tow, a landing craft equipped with up to 24 mortars,

we approached our designated landing area – Gold Beach, King, Red Sector. It was

a wet and windy night and the LCA crew had a most uncomfortable time. About a

thousand yards off the beach, the LCA slipped the tow and proceeded independently,

at some stage firing her spigots on to the beach near the German beach defences.

This allowed me to more safely beach in that area.

[Photo; Sub Lt Victor Bellars, Commander of

LCT 896].

H-Hour was 0723 but we

arrived 2 minutes early and received some spasmodic friendly fire. After hitting

the beach, we commenced the disembarkation of our petard

tanks. Our landing point was nearly opposite a pillbox, which we thought

contained an 88mm anti-tank gun. Our suspicions were confirmed when the first

tank off our LCT received a direct hit to its turret, totally disabling it. The 2nd tank didn’t fare any better but either

the 3rd or 4th tank* used its petard to deal with the

pillbox. At the same time a Hunt Class Destroyer, believed to be the Pychley,

fired 4 inch shells over my head at the pillbox. *(The Churchill AVRE with

a 290mm spigot mortar known as the Petard. This fired an 18 kg round over a

range of about 75m).

Untested innovations

usually went disastrously wrong. On D-Day-1,

we hitched a 20 foot canvas boat loaded with army stores to what would be the

last tank to disembark but it pulled the bow off the boat as it landed! With no

boat to gain the shore, the boat’s army personnel requested permission to go

ashore on foot. This was refused, because the incoming tide was gradually pushing

896 up the beach and they could easily have been crushed.

During our time on the beach, my gunners engaged any suitable targets.

Once our cargo was successfully disembarked I started to un-beach, when a signal

requesting assistance was received from Peter Conolly’s LCT 899, which was

firmly stuck on the beach nearby. We manoeuvred 896 short round (180

degrees) and drifted down so that the two craft were positioned stern to stern.

A heaving line was thrown and the tow passed over to 896, which was my 2½ inch kedge

anchor wire. For many months, I only used engines astern on full power to

un-beach rather than use the slow process of winching the craft off the beach

as it pulled against the anchor dropped on the approach.

I used about half a cable of my wire secured to my after-winch and eased

the power on until the wire was taut, then cleared the quarter deck and put on

full ahead. The second wave of landing craft was fast approaching and I didn’t

want them caught up in the tow. Fortunately LCT 899 came off the beach like a

cork out of a bottle. I kept going but eased the speed down to half ahead,

shortened the tow to about 10 fathoms and proceeded out to sea.

Two or three miles off Courseulles,

I anchored and brought 899 alongside. Some of their crew were transferred and some of both crews tried to effect

temporary repairs, since 899 was taking in water. I hoped that someone would find

us but I think we had drifted on the tide towards Le Havre, where the main

German coastal defences still posed a threat. We decided to wait until dark

before attempting to tow 899 home. After many hours steaming and encountering a

German warship, we reached the relative safety of Southampton's waters."

Juno Beach

(21,000 Troops) Juno Beach

(21,000 Troops)

At Courseulles sur Mer, on the Mike Red/Nan Green sectors of Juno beach, the men and craft of 'K' LCT

Squadron were present in support of the 7th Infantry Brigade of the 3rd Canadian

Division. Also present was LCT 2047 of the 102nd Flotilla. As she made her dash for the beach, her

port gunner, Able Seaman George Pardoe, manning the 20mm Oerlikon gun, noticed numerous LCAs (Landing Craft, Assault) running in alongside. He

then turned his attention to the beach ahead. On beaching, Pardoe

turned round expecting to see the approaching craft and, to his horror, he could

see only debris and floating bodies.

[Photo; Bodies and beached landing craft in

front of the sea wall on Nan Red beach, Juno area, near St

Aubin-sur-Mer, 6 June 1944. LCT 518 is on the right. LCA 522 on the

left. © IWM].

LCT 2243 was also present

with the 102nd Flotilla. At one point, she struck a mine and was lifted out of

the water by the bows but continued her run. During the approach, Wireman

(Electrician) David Johnson heard shouting and looked over the side to see a

soldier struggling in the sea. Attempts to reach the stricken man as 2243 passed

by failed and so did Johnson’s pleas to his commanding officer, Sub Lieutenant

Eric Wilkinson, to slow down in order to effect a rescue. However, the order of

the day for all commanding officers was

stark and simple... make for the beach, whatever the cost, do not stop, do not

pick up survivors.

A total of nine troopships were assigned to the first assault on Courseulles with the Canadian 7th Infantry

Brigade. One of them was HMS Invicta under the command of Acting Lieutenant Commander J R Law. LCAs of 510 Flotilla were lowered and

amongst the men of 510 was Seaman Ken Porter. He records that, as his LCA

approached the beach, he saw sailors and soldiers struggling in the water.

He wanted to stop and help but their orders that day were clear. "We had to

leave them, couldn’t stop, not allowed to stop, those poor lads, shortly after,

our craft hit the beach and the Canadians went off, I can still see them now,

those poor Canadians, dear God those poor Canadians."

East of Courseulles lay Bernieres sur Mer and St Aubin sur Mer,

where their beaches bearing the code names Nan White and Nan Red, were located. These sectors were assaulted by the men of the 8th Infantry Brigade of the 3rd

Canadian

Division. In support were the men and craft of ‘N’ LCT Squadron, comprising three flotillas of LCT with the 11th

Flotilla carrying the Sherman Duplex Drive ‘swimming tanks’ of the Canadian Fort Garry Horse. Mk3 LCT 317 lost Ordinary Seaman Sidney Bartley

and Stoker 1st Class Dennis Purnell.

Also in support was the Mk5 LCT(A)(HE)s of the 103rd

Flotilla of J2 Support Squadron transporting the Royal Marine Armoured

Support Group. Of the 103rd Flotilla, LCT(A) 2283 was totally

disabled as she made her dash for the beach after striking a mine or

being hit. She was left dead in the water and the crew were ordered to abandon ship. They spent the better part of D-Day in a ditch on the beach at St Aubin

but later became part of a beach clearing party. Amongst them was Seaman Howard

England, who spent two days

checking over wrecked and abandoned landing craft in the vicinity of Bernieres sur Mer and St Aubin. The LCT(HE)

2285 of the 103rd was also hit on D-Day and lost crew member Ordinary Seaman

Percy ‘Ginger’ Rogers. On D+1 he was buried at sea by his shipmates.

Sword Beach

(29,000 Troops)

Further east again was the beach

bearing the code name Sword. Its landing zones, named Queen Red and Queen White,

were at La Breche and Lion sur Mer respectively, the former being the most easterly. The first assault wave comprised the men of the 8th

Infantry Brigade of the 3rd British Division. With them went ‘E’ LCT Squadron, comprising four flotillas of LCT with 261 LCI(L)

(Landing Craft Infantry (Large) Flotilla. The 8th Brigade suffered heavy losses during the initial assault.

Several craft of the 45th Flotilla, delivering Royal Engineers, were

hit and in difficulty. Close behind them, some ten minutes late on H-Hour, was the Mk5 LCT of the 100th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla, delivering the 5th Independent Battery of the Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group. Several craft of the 45th Flotilla, delivering Royal Engineers, were

hit and in difficulty. Close behind them, some ten minutes late on H-Hour, was the Mk5 LCT of the 100th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla, delivering the 5th Independent Battery of the Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group.

[Photo; The American built, British manned,

MK5 LCT 2012 in the Far East. On the morning of June 6th, 1944, the then

LCT(A) 2012, was a unit of the 100th Flotilla. LCT(A) 2191 was of the

same design and specification].

For two craft of the 100th

Flotilla, the landing was a disaster. The LCT(A)s 2052 and 2191

beached on the easternmost flank of

Queen Red sector, 2191 being at the extreme with 2052 to her starboard (right). Having discharged their respective Centaur and Sherman tanks, a mobile German 88mm

approached from the immediate portside (left) of 2191. A crew member shouted a warning and commanding

officer, Sub Lieutenant Julian Roney, gave the order for the gun crews to open fire. However, against an 88mm, the men aboard 2191 stood little

chance.

The first shell to hit 2191 exploded to the immediate portside of the bow door. The blast killed Sub Lieutenant

Sidney Green (Photo) and Wireman (electrician) Edward Joseph Trendell, both of whom had been manning the portside winch (the mechanism for lowering and

raising the door or ramp). On the starboard winch were Leading Stoker Victor Orme

and Acting Able Seaman Robert "Geordie" Bryson. Both survived the initial blast

without serious injury. However, the

impact from the shell caused 2191 to turn to starboard, placing her broadside on

to the beach and, as tidal currents continued to turn the craft, her stern

became exposed to the beach and her tank deck, with ramp still in the down

position, became exposed to the open sea. The first shell to hit 2191 exploded to the immediate portside of the bow door. The blast killed Sub Lieutenant

Sidney Green (Photo) and Wireman (electrician) Edward Joseph Trendell, both of whom had been manning the portside winch (the mechanism for lowering and

raising the door or ramp). On the starboard winch were Leading Stoker Victor Orme

and Acting Able Seaman Robert "Geordie" Bryson. Both survived the initial blast

without serious injury. However, the

impact from the shell caused 2191 to turn to starboard, placing her broadside on

to the beach and, as tidal currents continued to turn the craft, her stern

became exposed to the beach and her tank deck, with ramp still in the down

position, became exposed to the open sea.

Gunner Roy Brown was manning the 20mm

starboard Oerlikon on 2191's quarter deck. He recalls that the craft soon

became engulfed by smoke obscuring his view of the beach and German targets sited there,

while the mobile German 88mm to portside (left), that was wreaking such

havoc aboard 2191, was taken out of his line of fire as the craft rotated.

Brown recalls a seaman named Heath, known by his shipmates as 'Darkie' owing

to his dark, weathered complexion, was manning

the port gun.

LCT(A) 2191's Coxswain, the man steering the craft onto the

beach, was a seaman named Lemon, affectionately known by his shipmates as

'Squash'. Brown recalls that he came from the London area. He was in fact

Francis Henry (known as Mark) Lemon, service number P/JX 330464. Shrapnel from

the first blast cut across the right side of his throat and right shoulder.

Although badly wounded, he managed to

reach the beach, where he was shot in the right thigh and the left ankle.

Despite all this trauma he survived the war, returned to accountancy, married

twice and had three children, one of whom, Stephen Lemon, provided this

information and advised that his father died in May 2014 in his 91st year. Not

surprisingly, his father didn't talk

much about his war service.

With

2191's bows and tank deck engulfed by smoke, Brown soon found his

position untenable. He left his gun station and made for the wheelhouse

but, soon after reaching it, a shell burst through and ricocheted around

the interior, finally exploding on the deck of the wheelhouse at Browns

feet. The upwards blast wounded Brown in the legs and back. He was stretchered off the craft,

transferred to a field hospital and, on Friday, June 9th, 1944, he arrived

back in England. With

2191's bows and tank deck engulfed by smoke, Brown soon found his

position untenable. He left his gun station and made for the wheelhouse

but, soon after reaching it, a shell burst through and ricocheted around

the interior, finally exploding on the deck of the wheelhouse at Browns

feet. The upwards blast wounded Brown in the legs and back. He was stretchered off the craft,

transferred to a field hospital and, on Friday, June 9th, 1944, he arrived

back in England.

[Photo left; Roy Brown

clutching a German helmet as a souvenir of his time in Normandy and

right,

Observation Officer

Richard Thornber].

Stationed on the bridge were 2191's Commanding Officer,

Sub Lieutenant Julian

Roney, Observation Officer, Richard

Thornber(1) and 19 year old Signalman Peter Hutchins. The second shell was as devastating as the first. Roney and Thornber, as far as can be certain, died where they stood,

leaving Signalman Hutchins alone. He tried to report to the wheelhouse but the explosion had destroyed the voice-pipe.

Undaunted,

Hutchins

climbed over the starboard side of the bridge, lowered himself to the gun deck

by way of the gun supports and gained entry to the wheelhouse. Through the forward slits he saw Orme and Bryson running towards him along the tank deck.

Just as they entered the

wheelhouse, 2191 was hit for the third time. Hutchins staggered but remained upright. He saw that his right ankle had been smashed and his foot was attached to his leg by

a tendon. Part of his uniform and overalls had been ripped away and his right boot and sock were missing. Amazingly Hutchins remained

standing but both Orme and Bryson lay wounded on the deck. Undaunted,

Hutchins

climbed over the starboard side of the bridge, lowered himself to the gun deck

by way of the gun supports and gained entry to the wheelhouse. Through the forward slits he saw Orme and Bryson running towards him along the tank deck.

Just as they entered the

wheelhouse, 2191 was hit for the third time. Hutchins staggered but remained upright. He saw that his right ankle had been smashed and his foot was attached to his leg by

a tendon. Part of his uniform and overalls had been ripped away and his right boot and sock were missing. Amazingly Hutchins remained

standing but both Orme and Bryson lay wounded on the deck.

[Photo left; Signalman Hutchins and right,

Robert ’Geordie’

Bryson].

Hutchins' immediate thought

was to leave 2191 to seek help for his stricken shipmates but he heard

voices from below and struggled over to a small open trap door in the floor of the wheelhouse.

He lowered himself down a steel ladder and lay face down on the mess deck.

Another shell struck and for a period he

lapsed into unconsciousness. On coming round, he heard cries of help and saw the mess deck was full of smoke,

the craft well alight and

munitions exploding. He retraced his steps to the wheelhouse where Orme and Bryson were in

great distress. Because of his injuries, Hutchins was unable to offer assistance to the men but, after a short rest, he

set off to summon help.

With great difficulty he crawled, hopped and shuffled his way to the still lowered bow door,

where he inflated his

lifebelt and lowered himself into the sea. The vessel was ablaze, munitions were exploding and

2191was still drifting eastwards some distance off the beach. Once in the water

and aided by the buoyancy of his lifebelt, he swan to the beach and lay face

down, exhausted and severely weakened through exertion, shock and loss of blood.

He had no sense of how the landings had gone but instinctively crawled to a

nearby sand-dune, always moving to the west. He rested many times and lapsed into periods of unconsciousness.

The

beach appeared to be deserted and he grew increasingly concerned about his own condition and

that of his shipmates. Two

soldiers came into view and, without knowing their nationality, he called for help.

Thankfully, they were survivors from a lost British

amphibious tank. He quickly briefed them on the plight of his two comrades still aboard 2191.

While one of the soldiers left to find a stretcher, the other

stayed with Hutchins. At moments of crisis the passage of time becomes distorted but he

recalled being

'stretchered' off to a first aid post on an adjacent beach to the west. Morphine was administered

to relieve his pain and the following day at a nearby field hospital, his right leg was amputated below the knee.

Hutchins had made valiant efforts to effect a rescue for his shipmates. In some desperation

to ensure his shipmates would be rescued, he enlisted the help of an

officer of senior rank, who undertook to send in a stretcher party as soon as possible. Shortly after, at 20.30 hours, a full 13 hours after

2191 had first beached, Hutchins saw vast numbers of parachutists dropping some distance inland. Unbeknown to him at the time, the trials and

tribulations of Bryson and Orme aboard the vessel were long since over, but with very different outcomes. Hutchins had made valiant efforts to effect a rescue for his shipmates. In some desperation

to ensure his shipmates would be rescued, he enlisted the help of an

officer of senior rank, who undertook to send in a stretcher party as soon as possible. Shortly after, at 20.30 hours, a full 13 hours after

2191 had first beached, Hutchins saw vast numbers of parachutists dropping some distance inland. Unbeknown to him at the time, the trials and

tribulations of Bryson and Orme aboard the vessel were long since over, but with very different outcomes.

[Photo; Peter Hutchins on a Channel ferry in June 2004. This was his first trip

to Normandy in 60 years... a long way from his New Zealand home. Photo courtesy

of Andy Bystram].

With the departure of Hutchins, Orme and Bryson were the last of the crew still alive and aboard

2191. Victor Orme was seriously injured and Robert Bryson most likely mortally wounded. Orme

lapsed into periods of unconsciousness and remained on board despite appeals

from Bryson for him to save himself but, when they felt heat coming through the wheelhouse deck

from the fire below, both men realised that Orme would have to leave to save himself... in fact Bryson insisted that he should go. What final words

passed between the men as Orme prepared to leave can scarcely be imagined. Orme was recovered from

the sea by soldiers, who were amazed at his escape from the then blazing wreck of 2191. that Orme would have to leave to save himself... in fact Bryson insisted that he should go. What final words

passed between the men as Orme prepared to leave can scarcely be imagined. Orme was recovered from

the sea by soldiers, who were amazed at his escape from the then blazing wreck of 2191.

[Photo right; Stoker Victor Orme].

Stoker Victor Orme, a one time member of the crew of HMS

AJAX, never forgot the tragic events of D-Day that left both physical and mental scars. Down the years,

as he watched the Remembrance Day Services at the Cenotaph, his thoughts

often turned to

Robert Bryson, when he could be heard to say, "Poor old Geordie, poor old

Geordie." Peter Hutchins too carried the

physical scars of D-Day for the rest of his life. A native of Leicester,

England, he emigrated to New Zealand after the war.

Little is known about the movements of Motor Mechanic, William

"Ross" Moore during the action. He was seen to jump into the sea off 2191's stern but, while swimming clear, he was killed by a shell

that exploded close by. Moore had a sense of foreboding about his fate on

D-Day, which had its foundation in the pennant number of his LCT adding up to

13. He even cautioned Electrical Artificer, Harry Ashurst against travelling on

2191 if given a choice. During his

schooldays in Brighton on England’s south coast, Moore proved himself to be a

good sportsman and later took up amateur boxing, making quite a name for himself. Little is known about the movements of Motor Mechanic, William

"Ross" Moore during the action. He was seen to jump into the sea off 2191's stern but, while swimming clear, he was killed by a shell

that exploded close by. Moore had a sense of foreboding about his fate on

D-Day, which had its foundation in the pennant number of his LCT adding up to

13. He even cautioned Electrical Artificer, Harry Ashurst against travelling on

2191 if given a choice. During his

schooldays in Brighton on England’s south coast, Moore proved himself to be a

good sportsman and later took up amateur boxing, making quite a name for himself.

[Photos above; Mechanic William

'Ross' Moore

in uniform, courtesy of veteran

Douglas Winter. See 'Acknowledgements'

below for more information. Right, ready to box].

Ashurst

was witness to the destruction of 2052 and 2191 on D-Day. The craft he

was on was crewed by Royal Marines and, as they

carried him towards Sword beach, he could see the two Mk5 LCTs on the beach. He

knew they were part of his flotilla and expected to go ashore close to

them

but, given the activity and congestion in the area, his craft was ordered away and beached further to the west.

Later he made his way back to 2052 and 2191 but by then it was over. Ashurst

was witness to the destruction of 2052 and 2191 on D-Day. The craft he

was on was crewed by Royal Marines and, as they

carried him towards Sword beach, he could see the two Mk5 LCTs on the beach. He

knew they were part of his flotilla and expected to go ashore close to

them

but, given the activity and congestion in the area, his craft was ordered away and beached further to the west.

Later he made his way back to 2052 and 2191 but by then it was over.

[Photos left above; Harry Ashurst on a Channel ferry in June 2004

(courtesy of Andy Bystram) and with a

limited edition print

that depicts the demise of the two LCTs].

Having

destroyed 2191, the German 88mm turned on 2052 to her starboard. As she attained the

beach, she too was hit and Sub

Lieutenant Lawrence Francis, who earlier felt 2052 was in a vulnerable position

on the exposed flank, fell, seriously wounded. His wounds ended his service in the Royal Navy. As

he lay wounded, a

shell passed through the wheelhouse, killing Coxswain Norman Hannah and

seriously wounding Able Seaman, Albert Smith and Telegraphist, John Royce.

All three spent a considerable time in hospital recovering. Having

destroyed 2191, the German 88mm turned on 2052 to her starboard. As she attained the

beach, she too was hit and Sub

Lieutenant Lawrence Francis, who earlier felt 2052 was in a vulnerable position

on the exposed flank, fell, seriously wounded. His wounds ended his service in the Royal Navy. As

he lay wounded, a

shell passed through the wheelhouse, killing Coxswain Norman Hannah and

seriously wounding Able Seaman, Albert Smith and Telegraphist, John Royce.

All three spent a considerable time in hospital recovering.

[Photos above; left Coxswain Norman Hannah

and right, Telegraphist John Royce].

Julian Roney, Richard Thornber, Sidney Green, Edward Trendell, Robert ‘Geordie’ Bryson, William ‘Ross’ Moore and Norman

Hannah, all lost from LCT(A)s 2052 and 2191, are at rest in

the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Hermanville, France.

%202_small.jpg) LCT(A) 2433 was also present with the 100th

Flotilla and had a narrow escape from friendly fire. On her approach to

the beach, a rocket firing LCT(R ), stationed at the rear, released her

salvo. One of its explosive rockets fell short and hit 2433’s bow door,

rendering it useless. After a struggle, the tanks successfully disembarked

2433 and unbeached with its downed ramp dragging in the sea. LCT(A) 2433 was also present with the 100th

Flotilla and had a narrow escape from friendly fire. On her approach to

the beach, a rocket firing LCT(R ), stationed at the rear, released her

salvo. One of its explosive rockets fell short and hit 2433’s bow door,

rendering it useless. After a struggle, the tanks successfully disembarked

2433 and unbeached with its downed ramp dragging in the sea.

[Photo; to the right 2433, centre background,

possibly

LCT(A) 2334 and left is LCT(A) 2432].

Denis Garrod of the Mk 4 LCT 980 of the 41st Flotilla recalls;

"I was the Wireman, 'Wires,' on D-Day. Our skipper was

Lt. Peter Gurnsey from Christchurch, New Zealand. Lt Gurnsey married a local

Scottish girl, Margaret Fowler from Catrine, who was a WREN serving in Combined

Ops at Troon. In December 1945, Peter returned to New Zealand with his

family. He was a very fine man, who died several years ago and was buried at sea.

At the wheel of LCT 980 was 20 year old Coxswain Bill Brentnall.

On the way in to Sword beach it was impossible to get into our sector

without striking a beach obstacle, of which there were two rows (see

photo opposite). The tide carried us over the first row but this was not

possible with the second row. Our skipper selected an obstacle and

intentionally hit it dead centre on our heavy steel landing ramp door.

As expected, the obstacle was mined and it blew a sizable hole in the

middle of the door. However, the hole was in such a position that the

disembarking vehicles were able to straddle it on their way onto the

beaches. It was my job to drop the kedge anchor and then to tear forward

to the port side winch locker, where a two man winch was provided for

raising

the door. There was a similar winch on the starboard side. At the wheel of LCT 980 was 20 year old Coxswain Bill Brentnall.

On the way in to Sword beach it was impossible to get into our sector

without striking a beach obstacle, of which there were two rows (see

photo opposite). The tide carried us over the first row but this was not

possible with the second row. Our skipper selected an obstacle and

intentionally hit it dead centre on our heavy steel landing ramp door.

As expected, the obstacle was mined and it blew a sizable hole in the

middle of the door. However, the hole was in such a position that the

disembarking vehicles were able to straddle it on their way onto the

beaches. It was my job to drop the kedge anchor and then to tear forward

to the port side winch locker, where a two man winch was provided for

raising

the door. There was a similar winch on the starboard side.

The troops were disembarked under the supervision of Sub Lieutenant Tait

and we proceeded to raise the door past the horizontal position. Tait took

the left handle from me and I quickly returned to the stern capstan to haul in the kedge anchor. As Tait

and AB Cyril 'Chesh'

Cheshire were manning the winch on the port side, an explosion occurred off the

starboard bow and a large piece of shrapnel flew in, striking Tait in the front

of the head, killing him instantly. Chesh told me afterwards that I missed

that one by a few seconds. We struck a beach mine as we came off in reverse

and that killed our rudders. Despite this setback, the skipper got us out to

sea a couple of miles, where Coxswain Brentnall stitched Sub Lt Tait's body into a hammock,

along with a heavy tank chock and he was committed to the deep." The troops were disembarked under the supervision of Sub Lieutenant Tait

and we proceeded to raise the door past the horizontal position. Tait took

the left handle from me and I quickly returned to the stern capstan to haul in the kedge anchor. As Tait

and AB Cyril 'Chesh'

Cheshire were manning the winch on the port side, an explosion occurred off the

starboard bow and a large piece of shrapnel flew in, striking Tait in the front

of the head, killing him instantly. Chesh told me afterwards that I missed

that one by a few seconds. We struck a beach mine as we came off in reverse

and that killed our rudders. Despite this setback, the skipper got us out to

sea a couple of miles, where Coxswain Brentnall stitched Sub Lt Tait's body into a hammock,

along with a heavy tank chock and he was committed to the deep."

[Photo

courtesy of Denis Garrod; Crew members back row l-r "Sparks" & Denis Garrod,

front row Chess, Harry, Mac and Jake].

[As a result of Denis Garrod's contact

with this website, forwarded to Tony Chapman of the LST and Landing

Craft Association, he and Bill Brentnall were reunited by telephone

after 60 years].

A newspaper article of the day reported on the experience of LCT 980.....

LONDON June 12th 1944. TANK FERRY. BEACH

LANDINGS. LIVELY TASK – DOMINION OFFICERS WORKING UNDER FIRE

"With one or two exceptions, it was the worst weather I have

experienced at sea in a tank landing-craft," said Sub-Lieutenant A P. Gurnsey

of Christchurch, commenting on the Channel crossing to France on D day. He was

one of very many New Zealand officers in landing craft of all types. "With one or two exceptions, it was the worst weather I have

experienced at sea in a tank landing-craft," said Sub-Lieutenant A P. Gurnsey

of Christchurch, commenting on the Channel crossing to France on D day. He was

one of very many New Zealand officers in landing craft of all types.

[Photo; New Zealander, Lt A P Gurnsey].

"My craft rolled like a barrel all the way," he said. "Our job

was to get the tanks ashore at the extreme left flank of the British front and

we ran into absolute hell. Our zero hour was 8.10 am and, by the time we

arrived, the Jerries had woken up and were ready to give us a warm reception.

They sniped and used mortars, both very unpleasant. In addition, there were

beach obstacles and mines fixed on tripods.

There were 12

landing-craft in our flotilla. It was a great sight to see them, line abreast,

going full speed for the beach. We avoided those obstacles we could but it

was a case of hit or miss.

One of the

mines blew a hole four foot wide in my ramp door but we got all our tanks

ashore. There were a lot of mortar bombs bursting everywhere. One, which

exploded on the beach, covered me with mud and water. It covered my craft too,

which was most annoying, seeing it had recently been given a nice new coat of

paint. In addition to mortar bombs, shells also were coming at us and my

starboard bow was a mass of holes about as big as your fist, caused by shell

splinters. Unfortunately my No.1 was killed.

When

all the tanks were ashore, I rang for emergency full astern for a quick

getaway, but no sooner were we afloat than a mortar bomb landed astern.

The explosion was so violent that it stopped both motors, which had to

be started up again. Then the coxswain reported that the wheel was

jammed amidships, which meant that we had no rudders and we were only

able to turn round by using the engines. It meant that we were sitting

under fire for about ten minutes longer than we should have been.

Fortunately everything went all right and we reached England under our

own steam." When

all the tanks were ashore, I rang for emergency full astern for a quick

getaway, but no sooner were we afloat than a mortar bomb landed astern.

The explosion was so violent that it stopped both motors, which had to

be started up again. Then the coxswain reported that the wheel was

jammed amidships, which meant that we had no rudders and we were only

able to turn round by using the engines. It meant that we were sitting

under fire for about ten minutes longer than we should have been.

Fortunately everything went all right and we reached England under our

own steam."

Two No 1’s in other LCTs, who

lowered the ramp doors on beaching, were Sub-Lieutenant M R M Glengarry of Wairoa

and A M W Bain of Gisborne. Sub-Lieutenant Bain’s craft took in some water

after hitting a mine but they carried on and successfully disembarked all their tanks.

Sub-Lieutenant Glengarry’s craft suffered four direct hits from mortar bombs,

which disabled all but one of the tanks she carried but, nonetheless, she made it ashore.

Sub-Lieutenant Glengarry was temporarily knocked out by concussion. "We felt

awful mugs bringing our tanks back when everyone else got theirs ashore,"

he

said.

Other New Zealanders in

landing-craft included Lieutenants I Lipanovic of North Auckland; D Lewis and K Todd of Auckland; T Bourke,

Lower Hutt; O B Reeve, Wellington; A Good, Taranaki; H Buchanan and F

Barnes, Invercargill. Sub-lieutenants were W Day, Nelson; D Hammond, Hawkes

Bay; W Coutts, Napier; K Bowe, Wellington; F Bishop, Christchurch; also E Chote,

E Krull, N Sutton, I Monaghan, E Richards and D Dodson.

The troopships assigned to Sword were

HMS Glenearn, Empire Battleaxe, Empire Broadsword and

Empire Cutlass. With them was the SS Maid of Orleans, carrying the LCA’s of 514 Assault Flotilla, delivering Commandos. Seaman Ray Maddison

of 514 recalled that immediately the Commandos had gone

ashore his LCA returned to seaward carrying a mortally wounded soldier of the 2nd Battalion The East Yorkshire Regiment,

when an explosion shook the beach and amongst the debris that passed over Maddison’s

head was a crucifix on a chain, perfectly intact. The owner of the crucifix

will never be known but Ray Maddison treasured it for the rest of his life. The troopships assigned to Sword were

HMS Glenearn, Empire Battleaxe, Empire Broadsword and

Empire Cutlass. With them was the SS Maid of Orleans, carrying the LCA’s of 514 Assault Flotilla, delivering Commandos. Seaman Ray Maddison

of 514 recalled that immediately the Commandos had gone

ashore his LCA returned to seaward carrying a mortally wounded soldier of the 2nd Battalion The East Yorkshire Regiment,

when an explosion shook the beach and amongst the debris that passed over Maddison’s

head was a crucifix on a chain, perfectly intact. The owner of the crucifix

will never be known but Ray Maddison treasured it for the rest of his life.

[Photo; Peter Hutchins

and Harry Ashurst together on a Channel ferry in June 2004. Photo

courtesy of Andy Bystram].

George Downing, on board HMS Glenearn, recalls;

"After disembarking our troops on the morning of D-Day, we

picked up some of the first wounded and returned to Blighty, where we urgently

embarked more troops to reinforce those already landed. Without a constant

supply of men, ammunition, vehicles and supplies, the advancing invasion force

would stall, giving the enemy time to regroup for a counter attack. Glenearn had

the capacity to

carry over1500 soldiers, making her ideally suited for her ferrying duties. We witnessed many consequences of war too

graphic to describe here but one of the most poignant was the suicide of an

American GI, who could not face the trials ahead and took his own life on the

quayside, while waiting to embark.

I also recall

Glenearn making a fast overnight

crossing accompanied by her sister ship, HMS Glengyle, with the frigate HMS Starling

in support. On an unrelated homeward trip, we met HMS Warspite returning to the beaches

after having her gun barrels replaced. Her gun turrets were later mounted at the

entrance to the Imperial War Museum in London as a fitting and lasting tribute.

Our ferrying duties

over, we were recalled to Greenock, where a surprise awaited us. We were

destined to go to the Far East."

Utah Beach (23,000 Troops)

A full hour before the British and Canadian landings on GOLD, SWORD and JUNO beaches, the men of the US 4th Infantry Division began

landing on the Uncle Red/Tare Green sectors of Utah beach. Transporting them

were the men of the US Navy and the Royal Navy’s ‘O’

and ‘G’ LCT Squadrons spread across the two landing zones. Also present that

D-Day morning, delivering the initial wave of the 1st Battalion

8th Infantry of the US 4th Division, was the Royal Navy’s

Empire Gauntlet lowering her LCA’s of 552 Flotilla.

East of Utah beach was the formidable cliff face of Pointe du Hoc, atop which, intelligence sources believed, were heavy

enemy guns.

In the D-Day

plan, Pointe du hoc was within the Omaha area but its heavy guns

could range over incoming craft and troops making for

both Omaha and Utah beaches. It was essential to silence these guns. The task was assigned

to the men of the US 2nd Ranger Battalion under the command of Colonel James Rudder. Royal Marine, John Lambourne was present serving with the LCS(M) (Landing Craft Support (Medium) 102 of 901 Flotilla. He and his crew were

assigned to the troopship Prince Leopold, which carried the LCAs of the Royal Navy’s 504 Flotilla. LCS(M) 102 was

also present in support as LCAs

carrying the Rangers made their way to the beach. Lambourne watched in awe as the Rangers attained the beach and began scaling the cliff by way

of grappling hooks fired from their LCAs. The memory of the bravery he witnessed remained

forever with him.

Omaha Beach

(34,000 Troops) Omaha Beach

(34,000 Troops)

Many tragedies were played

out on Omaha beach, which was assigned to the men of the US 1st and 29th

Infantry Divisions. The initial wave of Company A of the 116th

Infantry Regiment, landing on Dog Green sector, was decimated. The greater part

of 200 men perished on the beach or in the water. Company A were carried in by LCAs of the Royal Navy’s 551 Flotilla off

the troopship Empire Javelin. Seaman William ‘Bill’ Wain on one of the LCA's carrying them in, to the best of his knowledge and belief

remembers all the

men he landed were lost.

[Photo; Landing craft carrying the first US assault waves head

towards the beach in Dog sector, Omaha area, 6 June, 1944.© IWM (EA 25648)].

What befell the assault troops on Omaha beach has been well documented, not for nothing is it remembered as ‘Bloody Omaha’. Later in the

morning, the Royal Navy’s LCT 1000 of ‘Q’ LCT Squadron approached the beach but congestion

delayed her beaching. On

her bridge were her commanding officer, Skipper Albert Wiseman and Signalman Arthur Tarr. Wiseman scanned Omaha beach with binoculars.

Countless bodies were strewn across the beach and in the water, while wrecked craft littered the water's edge. Wiseman

passed his binoculars to Tarr, who soon

turned away...sickened.

The Fallen

For many months, if not

years, before D-Day, the men of the land and sea forces trained together as they

honed their skills in the use of landing craft with support from their air force

colleagues. On the morning of June 6th,

1944, they bravely fought and thousands died together in Normandy, where they remain,…

together…for eternity.

Photographs shown here are some collected from wrecked and abandoned landing craft by Howard

England on D-Day, serving with the LCT(A) 2283 of the 103rd Flotilla.

Nothing is known of the men depicted here. I have no way of knowing if they were

even present on the day but I sense they were. I also hope they

survived. Photographs shown here are some collected from wrecked and abandoned landing craft by Howard

England on D-Day, serving with the LCT(A) 2283 of the 103rd Flotilla.

Nothing is known of the men depicted here. I have no way of knowing if they were

even present on the day but I sense they were. I also hope they

survived.

Visit

Operation

Overlord - the D-Day Landings for background information to the landings and a general

perspective of events on the day.

One Mystery Solved thanks to Robert Dodds,

a motor mechanic on LCT 2286 contacted us in August 2009. He wrote;

"The photograph of two people

immediately above "Further Reading" shows Edward Jevet (left) and Ted Ballard

(right). They both survived the war. They were stokers on LCT 2286, which went

into Juno beach. Thanks for the web site. I found it very interesting. Regards,

Robert Dodds.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and

landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on

our 'Combined Operations Books' page. They, or any

other books you know about, can be purchased on-line from the

Advanced Book Exchange (ABE). Their search banner link, on our 'Books' page, checks the shelves of

thousands of book shops world-wide. Just type in, or copy and paste the

title of your choice, or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions.

There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Being in All Respects Ready for Sea.

Written by the skipper

of a Mark 4 LCT, Hubert G Male. James Publishing, London, 1992, 184 pages, 1 85756 030 2

Acknowledgments

This

account of life on WW2 Landing Craft

presents some brief glimpses of specific events seen from the perspective of

those manning the various landing craft on D-Day. It was transcribed from notes

received from veterans and their families by Tony Chapman, Archivist/Historian for the LST and

Landing Craft Association and further edited by Geoff Slee for presentation on

the website.

As acknowledged above, the photo of Bill Moore in uniform was

supplied by veteran Douglas Winter, who grew up and attended school with Bill in

Newhaven, Sussex, England. Douglas knew his great pal Bill had been killed on

D-Day but not the manner of his loss until reading this web page. On D-Day,

Douglas arrived off Juno beach serving in HMLST(2) 413 of Temporary Acting

Lieutenant Commander R J W Crowdy RNVR. LST 413 was part of the 2nd LST

Flotilla of Assault Group J3.

Footnote(s).

1. Sub Lt Richard

Thornber RNVR HMLCT(A) 2191. Richard Thornber, 26,

came from Darwen in Lancashire. A well-built, popular man he swam competitively

and played full back for Darwen Football Club. In 1939, he joined the Liverpool

Police force and in 1940 was awarded a Humane Society silver medal for stopping

a runaway horse and cart. In October 1941, he joined the RAF and became a pilot

until damage to his eyesight led him to join the RNVR being assigned to Combined

Operations.

Richard died in the knowledge that his wife was expecting

their first child, who grew up ignorant of her father’s precise fate until 2005

when, as a result of finding this website, she spoke to Signalman, Peter

Hutchins of HMLCT(A) 2191 and to flotilla Electrical Artificer Harry

Ashurst.

|

Making her way to Gold beach that morning as part of the 109th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla was LCT

(A) 2039. The craft were carrying Centaur and Sherman tanks of the 1st Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group. They were part of the 'first assault' on King sector of Gold beach, to the west of La Riviere,

in support of the 69th Infantry

Brigade of the British 50th Division. Sadly 2039 was swamped and turned turtle

in the early morning hours when some 20 miles off the

beaches. Two crew members, Able Seamen Illingworth and Donnelly were

lost.

Making her way to Gold beach that morning as part of the 109th LCT(A)(HE) Flotilla was LCT

(A) 2039. The craft were carrying Centaur and Sherman tanks of the 1st Royal

Marine Armoured Support Group. They were part of the 'first assault' on King sector of Gold beach, to the west of La Riviere,

in support of the 69th Infantry

Brigade of the British 50th Division. Sadly 2039 was swamped and turned turtle

in the early morning hours when some 20 miles off the

beaches. Two crew members, Able Seamen Illingworth and Donnelly were

lost. Sub Lieutenant Victor Bellars

was in command of LCT 896. He recalls; "With a spigot LCA(HR) in tow, a landing craft equipped with up to 24 mortars,

we approached our designated landing area – Gold Beach, King, Red Sector. It was

a wet and windy night and the LCA crew had a most uncomfortable time. About a

thousand yards off the beach, the LCA slipped the tow and proceeded independently,

at some stage firing her spigots on to the beach near the German beach defences.

This allowed me to more safely beach in that area.

Sub Lieutenant Victor Bellars

was in command of LCT 896. He recalls; "With a spigot LCA(HR) in tow, a landing craft equipped with up to 24 mortars,

we approached our designated landing area – Gold Beach, King, Red Sector. It was

a wet and windy night and the LCA crew had a most uncomfortable time. About a

thousand yards off the beach, the LCA slipped the tow and proceeded independently,

at some stage firing her spigots on to the beach near the German beach defences.

This allowed me to more safely beach in that area.

With

2191's bows and tank deck engulfed by smoke, Brown soon found his

position untenable. He left his gun station and made for the wheelhouse

but, soon after reaching it, a shell burst through and ricocheted around

the interior, finally exploding on the deck of the wheelhouse at Browns

feet. The upwards blast wounded Brown in the legs and back. He was stretchered off the craft,

transferred to a field hospital and, on Friday, June 9th, 1944, he arrived

back in England.

With

2191's bows and tank deck engulfed by smoke, Brown soon found his

position untenable. He left his gun station and made for the wheelhouse

but, soon after reaching it, a shell burst through and ricocheted around

the interior, finally exploding on the deck of the wheelhouse at Browns

feet. The upwards blast wounded Brown in the legs and back. He was stretchered off the craft,

transferred to a field hospital and, on Friday, June 9th, 1944, he arrived

back in England.

%202_small.jpg)

At the wheel of LCT 980 was 20 year old Coxswain Bill Brentnall.

On the way in to Sword beach it was impossible to get into our sector

without striking a beach obstacle, of which there were two rows (see

photo opposite). The tide carried us over the first row but this was not

possible with the second row. Our skipper selected an obstacle and

intentionally hit it dead centre on our heavy steel landing ramp door.

As expected, the obstacle was mined and it blew a sizable hole in the

middle of the door. However, the hole was in such a position that the

disembarking vehicles were able to straddle it on their way onto the

beaches. It was my job to drop the kedge anchor and then to tear forward

to the port side winch locker, where a two man winch was provided for

raising

the door. There was a similar winch on the starboard side.

At the wheel of LCT 980 was 20 year old Coxswain Bill Brentnall.

On the way in to Sword beach it was impossible to get into our sector

without striking a beach obstacle, of which there were two rows (see

photo opposite). The tide carried us over the first row but this was not

possible with the second row. Our skipper selected an obstacle and

intentionally hit it dead centre on our heavy steel landing ramp door.

As expected, the obstacle was mined and it blew a sizable hole in the

middle of the door. However, the hole was in such a position that the

disembarking vehicles were able to straddle it on their way onto the

beaches. It was my job to drop the kedge anchor and then to tear forward

to the port side winch locker, where a two man winch was provided for

raising

the door. There was a similar winch on the starboard side.