|

Operations Neptune & Overlord - The D Day Landings.

Normandy 6th June 1944

Background

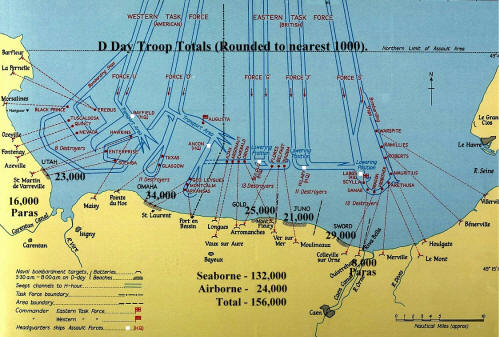

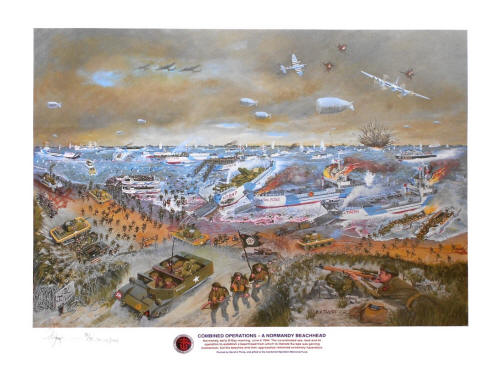

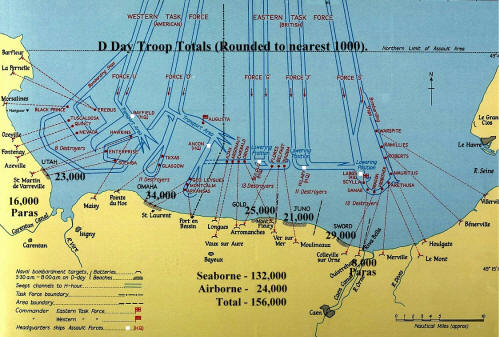

Operation Neptune, the largest amphibious invasion

force in history, was the seaborne phase of Operation Overlord. On June 6th

1944, 4,000 landing craft, supported by 3,000 naval combat

ships, ancillary craft and merchant vessels, transported 132,600

assault troops from the south coast of England to the

Normandy beaches, together with thousands of tons of

vehicles, tanks, supplies and ammunition.

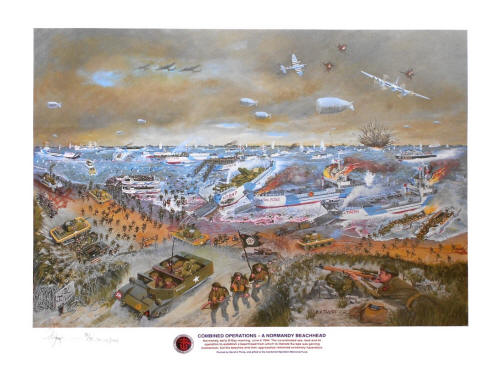

[Image; Print of

painting by David A Thorp entitled

'Combined Operations - A Normandy Beachhead'].

Earlier, 23,400 paratroops were dropped behind enemy lines, 15,500

in the American sector and 7,900 in the British/Canadian

sector. Their mission was to

capture strategic bridges, road junctions and installations.

Meanwhile, RAF and USAF

bombers and fighters flew in support of the initial assault

troops to soften up beach defences in advance of the landings and to destroy targets inland

identified by Forward Observation Officers and the advancing troops.

Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour the Allies created the

"Combined Chiefs of Staff" (CCS) comprising the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff and the British Chiefs of Staff. Their function was

to assist and advise President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill on the direction and conduct of the war. The CCS confirmed a previous

policy of "Germany first" and, from March 1942, their planning group began work on an outline plan for a full-scale invasion of

occupied Europe.

Initial hopes of mounting an invasion in 1943 proved unrealistic with limited

human and material resources and the demands of already agreed commitments on other operations.

The invasion was delayed until 1944 despite persistent agitation from Stalin to open a second front

in the west to relieve pressure on his forces in the east.

The CCS planning

group, with the lessons learned from the ill

fated Dieppe raid

in their minds, ruled out a frontal attack on a

fortified port so determined to find safer landing sites. The requirements for a suitable landing site were for it

to;

-

be within range of fighter aircraft based in southern England,

-

have at least one major port within easy reach,

-

have landing beaches suitable for prolonged support operations, with

adequate exits and backed by a good road network,

-

have beach defences

capable of being suppressed by naval bombardment and

bombing.

The Normandy coast between Caen and Cherbourg met these

requirements and they prepared a basic outline paper in support of this proposal which was approved by the CCS.

In March 1943, Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of

Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC). The Normandy coast between Caen and Cherbourg met these

requirements and they prepared a basic outline paper in support of this proposal which was approved by the CCS.

In March 1943, Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of

Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC).

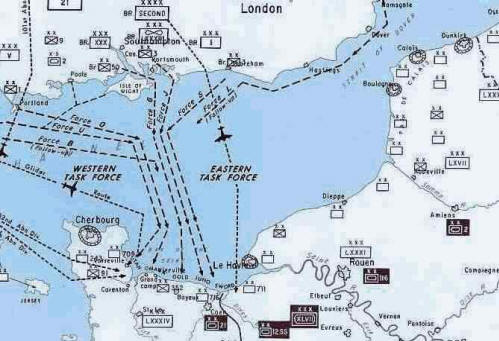

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

His heavy responsibility was to

prepare detailed plans for the largest amphibious invasion force in

history. In doing so his plans would utilise the

combined forces of the three mainstream services of the participating

Allied nations. Morgan was an excellent choice having been involved as a

task force commander in the 1942 invasion of North Africa and in the preliminary planning for the invasion of Sicily which was to take place in July 1943.

The ultimate goal was to

secure Germany's unconditional surrender through the destruction of its armed forces

if necessary. Morgan

worked backwards from that outcome to determine what manpower and material

resources would be required to complete the task. It was a complex task of

monumental proportions which would produce detailed plans down to specific

landing areas, at specific times, with specific orders for all involved. The

overall invasion plan was given the codename "Overlord" with the

amphibious phase codenamed "Neptune."

The Assault Plan

American General Dwight D Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Allied Commander in December 1943

and as his senior commanders took up their posts, the original plan was modified. The ground commander,

during the initial assault phase and subsequent beachhead build up, was British

General Bernard Montgomery. He increased the extent of the landing beach spread

from around 25 miles to 50 miles and increased the size of the initial assault

from 3 to 5 divisions, together with an additional 2 American airborne divisions and 1 British airborne division

of paratroops. Their primary task was to seize vital bridges and crossroad

strong-points at each extremities of the invasion area to protect the eastern and western

flanks from counterattack during the initial landings.

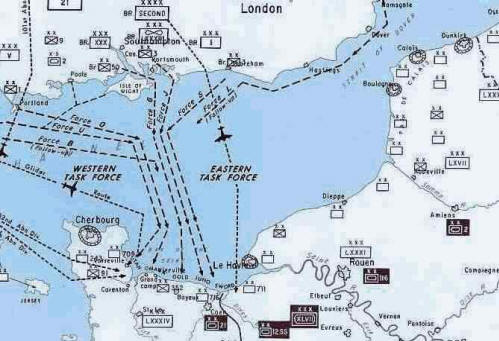

The assault force

itself was divided into an American western task force landing on two beaches and a

British and Canadian eastern task force landing on three beach areas in the eastern

section. Commando and US Ranger forces, as part of the initial assault, were to neutralize specific coastal strong-points

thought to be too difficult for regular infantry to tackle successfully. The assault force

itself was divided into an American western task force landing on two beaches and a

British and Canadian eastern task force landing on three beach areas in the eastern

section. Commando and US Ranger forces, as part of the initial assault, were to neutralize specific coastal strong-points

thought to be too difficult for regular infantry to tackle successfully.

On D Day,

each of the 5 assault forces was to secure their respective beachheads and to

progress inland. On D+1 the separate beachheads were to combine into one

continuous front. During D+2 to D+9 they should form a secure staging area to

accommodate the substantial follow up forces and their supplies and equipment.

The plan then envisaged a

breakout towards Paris and the Rhine but the senior Allied commanders

knew a crucial race against the Germans would come into play. To succeed in this,

the Allies' build up of their forces in the beachhead area, would need to be faster than the Germans'

build up of forces to mount an effective counter attack. To impede the movement of German men, supplies and armour, road and rail communications across the north of France were

bombed intensively prior to the landings but over a wider area than necessary to

prevent the enemy from identifying the landing beaches.

Lessons learned on previous raids and landings were incorporated into the

overall plan on D-Day, including extensive bomber, fighter and naval bombardment support and improved radio communications at all levels.

Novel techniques and equipment were adopted to overcome enemy beach obstacles

while under enemy fire on heavily

defended open beaches. These were most likely used on the British and Canadian

beaches, where specialized armoured units led the attack. Former Major General,

Percy Hobart, an eccentric lateral thinker, was personally selected by Churchill to

modernize Britain’s tank program. He developed so called "Hobart's

Funnies" which included the "flail tank", whose rotating drum and chains

cleared paths through mine fields, while other adaptations were designed to clear

tank obstacles and pill boxes and to lay down pathways to aid movement of heavy

wheeled vehicles over soft

sand.

There was no guarantee that a working harbour

would fall into Allied hands since they were heavily defended and would be

destroyed in the event of a

determined attack. Although supplies could be landed on the beaches, a fully functioning harbour

would provide relatively safe and secure docking facilities less susceptible to

the vagaries of tide and weather. Many thousands of tons of supplies and equipment

needed to be landed each day during the build up period. One planner suggested that

the invasion force should "take a harbour over with them" an idea Churchill

had considered during WW1. Twenty thousand workers laboured for eight months to construct an

ingenious solution to the challenge which became known as "Mulberry Harbours".

They were installed in both American and British sectors.

There were a number of

disparate factors that determined the date of invasion given that it would take

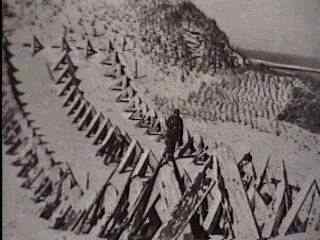

place just after dawn. Amongst these, were Rommel's extensive beach obstacles,

which would become visible and thereby more easily destroyed by engineers during

a low or rising tide. Those being dropped behind enemy lines the night before the landings

required sufficient moonlight for the airborne forces (parachutes and gliders)

to find their predetermined targets. These and other factors restricted the periods of

opportunity in June to

the 5th, 6th, 7th or 19th.

The German Defences

"It is my unshakeable decision to make this front impregnable against every enemy"

declared Hitler in a speech he delivered in December 1941 when he

boasted, to the world, that Germany controlled the entire west coast

of Europe from the Arctic Ocean to the Bay of Biscay. His impregnable

defences included some 15,000 strong-points which were to be manned by

300,000 troops. "It is my unshakeable decision to make this front impregnable against every enemy"

declared Hitler in a speech he delivered in December 1941 when he

boasted, to the world, that Germany controlled the entire west coast

of Europe from the Arctic Ocean to the Bay of Biscay. His impregnable

defences included some 15,000 strong-points which were to be manned by

300,000 troops.

Construction of

the obstacles officially started in early 1942. For 2 years, a quarter of a million, mainly slave labourers, worked night and

day. They used more than a million tons of steel and poured over 20 million cubic yards of concrete. The heaviest concentration of defence works

was along the narrowest part of the English Channel between the Netherlands and Le Havre in Normandy.

It was no secret that the Allies were building up to an

invasion, although the location and timing were beyond 'top secret' and known only

to a select few. In November 1943, Hitler appointed Field Marshall Rommel, initially to the position of Inspector of Coastal Defences and later to the command of Army Group B, which occupied the channel coastal defences.

He moved to France in December 1943 and immediately set about further

improvements to the defences.

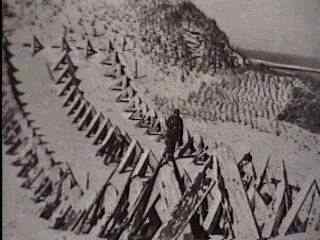

He planned an impassable zone, initially100 metres deep, along the whole channel

coast, which would be extended to a kilometre by deploying 200 million mines. He dramatically

accelerated the rate of construction and, by May 11th, over half a

million mines had been laid along the channel

foreshore and on likely glider and parachute landing zones behind the beaches. Additionally, some areas immediately behind the beaches, were

deliberately inundated with water to further inhibit movement off the beaches

and to contain the Allies.

In

November 1943, in anticipation of an amphibious invasion in the west, Hitler

issued

Fuhrer Order 51.

Meantime, Rommel planned to stop and contain the invading force on the beaches,

since the Allies

air supremacy would inhibit the daytime movement of his troops and tanks once battle

was joined; a lesson he learned to his cost in North Africa.

As part of this strategy,

he planned to locate enough Panzer (Armoured) divisions, sufficiently close

by, to counter attack and overrun the beachheads before they became established.

From May onwards the Germans braced themselves for an attack and were puzzled when the relatively mild

weather of May passed by without incident. They took the opportunity to complete more

beach obstacles. Rommel was now sure that his improved "Atlantic Wall"

would hold the enemy on the beaches and believed the Allies would attack on a high tide at

dawn. These two conditions coincided for a few days around the middle of June.

Rommel didn't know that General Eisenhower

had set the invasion date for June 5th. However, in the event, bad

weather caused a postponement of 24

hours. It was an unwelcome delay for the combat ready force and even more so for

those onboard ships recalled while at sea. On June 6th the armada of over 5,000

vessels set off. It comprised minesweepers, heavy battleships, troop carriers,

landing craft of many types, HQ ships and Fighter Direction

Tenders to provide extended radar and communications cover off the Normandy

beaches.

D-Day – June 6th 1944

The Airborne Forces

Hours before daylight,

over 1000 bombers dropped their payloads on German coastal defences to soften

them up prior to the arrival of the initial assault troops. Additionally, over 800 planes dropped

paratroops or towed gliders to pre-determined locations behind enemy lines. To

add to the confusion and alarm other bombers parachuted hundreds of dummies all

over Normandy.

Shortly after midnight, the American 101st and 82nd airborne divisions parachuted

into their prescribed landing zones at the base of the Cotentin peninsula to the

west of the invasion area. Some planes deviated from their final approach

because of cloud and flak with unfortunate consequences. Many

paratroopers, who landed in areas deliberately inundated by the enemy, drowned

but despite these losses these elite troops secured their main objectives and

held on grimly – their link up with the main sea-borne landings was only hours

away.

The British 6th airborne division of paratroopers and a special task force in

gliders, simultaneously landed in the east side of the invasion area. The glider task force quickly

captured the key bridges on the Orne River and Caen Canal. After a fierce fight, a substantially under strength paratrooper force subdued the Merville battery, which was a threat to the approaching Allied invasion fleet. The vanguard airborne troops landings were considered a heartening success.

The Sea-borne Forces The Sea-borne Forces

The thousands of ships and landing craft of the

invasion fleet arrived off the beaches before dawn. Despite a slight improvement

in the weather, gusty winds churned up five to six foot waves in the English

Channel and most of the 132,000 seaborne assault troops suffered from seasickness.

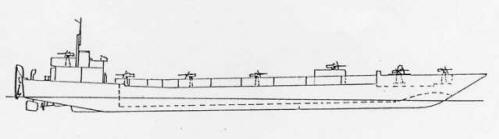

[Photo left - LCT Flotillas in Southampton

prior to departure for Normandy].

Stan Grayland (photo below right) recalls... for four days

our Landing Craft Flack, ( LCF 30), numbered because such small ships were not

permitted names, sat tied to a buoy off Whale Island, the Royal Navy Gunnery

School at Portsmouth, on the South Coast of England. LCF 30 was sealed, meaning

no one could leave the craft and was readied for what everyone knew was

inevitable... the invasion of France, considered to be the beginning of the end

of World War 2... D-DAY.

It was Monday June 5th 1944 and our craft, together with some 4000 other

forms of shipping with thousands of fully trained men lifted themselves, took

up their stations and, with a last wave to onlookers on the shore, headed slowly

out into the English Channel to assemble on the southern side of the Isle of

Wight. In the early evening, with high winds and rough seas, the journey to

France was about to begin.

Large passenger vessels crammed with troops, minesweepers, escort ships

scurrying about, large warships and landing craft took up their p1aces ready

to move off and the men entrusted

with the initial assault looked, thought and wondered where

they would be

tomorrow. Barrage balloons floated above at the end of steel ropes to deter low

flying aircraft from attacking the invasion force. They were blown from side to

side in the strong winds and the men watched the choppy seas and knew it would

be a very uncomfortable trip ending with disembarkation onto heavily defended

enemy held beaches. Sadly the journey for some would end all too soon. Large passenger vessels crammed with troops, minesweepers, escort ships

scurrying about, large warships and landing craft took up their p1aces ready

to move off and the men entrusted

with the initial assault looked, thought and wondered where

they would be

tomorrow. Barrage balloons floated above at the end of steel ropes to deter low

flying aircraft from attacking the invasion force. They were blown from side to

side in the strong winds and the men watched the choppy seas and knew it would

be a very uncomfortable trip ending with disembarkation onto heavily defended

enemy held beaches. Sadly the journey for some would end all too soon.

"Action Stations" for the men of LCF 30 required the manning of small Pom-Pom and Oerlikon anti aircraft guns throughout the night, not knowing what

the morning would bring. For most of those 18 and 19 year olds, this was to be

their first big adventure. Hundreds of planes flew overhead, some to drop bombs

on the beach defences, some to slow down the deployment of enemy reinforcements

and some troop carrying planes towing gliders packed full of troops with the

task of landing

silently to

capture strategic positions before the main assault force had landed.

At sea the invading armada kept steadily on, no lights were visible.

"Maintain your station" was the order, a very difficult thing to achieve with

flat bottomed craft with no hull. Collisions at sea at this crucial time would

be disastrous and could not be allowed to happen. During the night, the coast of

France came into view. Along the 80 kilometre of landing beaches, fires caused by bombing and shelling

were visible. At this

early stage there was no indication that the enemy knew we were coming.

Sometime around 6.30am, and still some 8 kilometres from the beach, the

ships carrying the assault troops hove too. The assault landing craft, LCAs

were lowered, mostly with men already in their allotted places and then, when

all were in place, escorts like LCF30, turned to the beach and the dangerous journey began..... Sometime around 6.30am, and still some 8 kilometres from the beach, the

ships carrying the assault troops hove too. The assault landing craft, LCAs

were lowered, mostly with men already in their allotted places and then, when

all were in place, escorts like LCF30, turned to the beach and the dangerous journey began.....

Two things remain vividly in my memory. The first were the Rocket

ships that went in with us. They carried 1020 5 inch rockets and on each firing

of say 30 rockets, at least 1 would misfire and after wobbling its way out of

the launcher would land amongst the assault craft. My guess is there were more

casualties on landing craft at sea caused by them than any enemy fire from the

beach. And my second memory is of the sky being full of planes in the early

evening, Stirling bombers towing gliders - the planes dropping supplies and the

gliders landing men some 1 or 2 miles inland. Then, when darkness came, we took

station in TROUT LINE, where we were able to watch the tracer bullets being

exchanged between sides.

German coastal batteries started firing

on the fleet at 5.30 am and the Allied naval bombardment countered at 6 a.m.

The battleships and cruisers were about 6 miles off the beaches and the

destroyers held off at about 4 miles. As the orange flames from their gun

muzzles lit up the dawn, the thunderous noise of their bombardment rolled up and

down the coast. The bombardment detonated some large minefields and knocked out

a few defensive positions but the clouds of smoke and sand soon made the shore

almost invisible. Many German strong points escaped serious damage. German coastal batteries started firing

on the fleet at 5.30 am and the Allied naval bombardment countered at 6 a.m.

The battleships and cruisers were about 6 miles off the beaches and the

destroyers held off at about 4 miles. As the orange flames from their gun

muzzles lit up the dawn, the thunderous noise of their bombardment rolled up and

down the coast. The bombardment detonated some large minefields and knocked out

a few defensive positions but the clouds of smoke and sand soon made the shore

almost invisible. Many German strong points escaped serious damage.

The American western

task force approached their landing beaches codenamed

Utah and Omaha. The US 4th division was scheduled to land on the westernmost beach (Utah) at the foot of the Cotentin peninsula. When about 300 yards off the beach, they fired smoke signals

high in the air; the signal to end the coastal bombardment and to target enemy defensive positions further inland. At 6.31

am the first amphibious soldiers to land in France on D-Day walked off their landing craft into waist deep water and waded 100 yards to dry

land. There was surprisingly little response from the German defenders. Many Germans had been killed and their guns destroyed by the

preliminary bombardment and many survivors were too dazed to provide an effective response. The beach area was cleared inside 3 hours

and some 23,000 men and 28 tanks landed. Casualties were less than 200.

The next beach to the east, Omaha, was an entirely different matter. The US 1st

division ran into heavy artillery and machine gun fire as soon as the landing

craft ramps were lowered. A lateral current along the shore had badly scattered

the men and their units and in the confusion the exceptionally strong German

fire took its heavy toll on the initial assault units. Many wounded men were

drowned in the rising tide and the initial assault stalled at the waterline.

To compound the problems on Omaha, only around 58 of the 112

planned tanks reached the beach. A number of Sherman DD 'swimming' tanks

disembarked into the sea too far out and floundered, leaving many troops opposing

the enemy's beach strong-points with their personal weapons. Destroyers from the

bombarding fleet moved in as close to the beach as they dared to provide some

covering fire. The outcome was in doubt for the first 3 hours and only through

improvisation and courageous personal leadership were the troops at last able to

get off the beach and onto the heights beyond. By nightfall, some

34,000 men were ashore at a cost of 2,000 casualties. At this point the

beachhead was only 2 miles deep.

Two US Ranger battalions scaled the 100-foot high cliffs at Point du Hoc, three miles west of Omaha Beach,

to silence six 155mm German howitzers believed to be in the battery. These

mobile guns had recently been moved one mile inland to new positions and by

nightfall the Rangers had suffered 60% casualties in attacking the defending German troops and beating off

their counterattacks. Despite these

losses, the Rangers located

the guns and put them out of action. Two US Ranger battalions scaled the 100-foot high cliffs at Point du Hoc, three miles west of Omaha Beach,

to silence six 155mm German howitzers believed to be in the battery. These

mobile guns had recently been moved one mile inland to new positions and by

nightfall the Rangers had suffered 60% casualties in attacking the defending German troops and beating off

their counterattacks. Despite these

losses, the Rangers located

the guns and put them out of action.

[Photo; Troops from

50th Division coming ashore from LSI(L)s - Landing Ship Infantry (Large). Gold

area, 6 June 1944. IWM].

The 3 beaches to the

east of the invasion area, codenamed respectively Gold, Juno and Sword, were the

responsibility of the British Second Army's Eastern task force. Their landings

commenced around almost 7.30 am to accommodate the tidal conditions in that area

and their plan to beach on a rising tide. On Gold beach, nearest to Omaha, the 50th Division and the 8th

Armoured Brigade were scheduled to land with the tanks in the vanguard. Some

initial assault units were pinned down by accurate German fire, while others overran the

German defences within half an hour. Subsequent waves flanked the defenders and

pushed inland. By nightfall they had advanced about 2.5 miles inland on a front

of 3 miles. However, there remained a seven mile gap between them and Omaha.

The Canadian 3rd

Division landed on Juno beach and met stiff initial resistance. Due to choppy

seas they were half an hour behind schedule leaving little time for the assault engineers to clear beach obstacles before the

incoming tide covered them. The mined obstacles and German shell fire disabled

or sunk around 90 of the 306 landing craft but the Canadians attacked

furiously and refused to be stopped. Some sections of the landing beach were strongly

defended, which delayed the advance until the afternoon, while other parts were

quickly overrun, allowing the assault troops to move rapidly inland. By the end of the day, they had almost reached their final D-Day

objectives and were astride the vital Caen/Bayeux highway. They manage to link up with British troops from Gold beach and by the end of the day

their beachhead was 12 miles wide and 6 miles deep; but they were still 3 miles short of linking up with the British forces on their left – the

Sword force.

Bill Newell a young Canadian Commando recalls;

It was an event beyond imagination. The

magnitude of activity was such that one could not take it all in but yet could

easily understand its purpose. The difficulty was in comprehending that I was

part of it all.

After a year of extremely

arduous navy commando training in the hills of Scotland, our small Canadian unit

was expected to be conditioned and ready for most circumstances anticipated in

such an operation. In relieving a British commando unit, we were not the first

to hit the beach but that did not dissipate the feeling of apprehension, nor

did it affect the sense of confidence earned by our training.

There were ships of all types

and sizes, from battleships with 15 inch guns firing inland over the beach,

destroyers and minesweepers sweeping in closer, smaller supply trawlers, and

many different landing craft going in full and coming out empty. There were

heavy-duty tugs manoeuvring huge sections of floating steel docks into position

together with damaged and crippled ships to form a line of sunken

breakwater. This would

reduce the wave action on the beach. There were ships of all types

and sizes, from battleships with 15 inch guns firing inland over the beach,

destroyers and minesweepers sweeping in closer, smaller supply trawlers, and

many different landing craft going in full and coming out empty. There were

heavy-duty tugs manoeuvring huge sections of floating steel docks into position

together with damaged and crippled ships to form a line of sunken

breakwater. This would

reduce the wave action on the beach.

Wreckage of landing craft and

armoured vehicles were impediments to be avoided until conditions permitted

their salvage. The water was cluttered with the debris of combat from enemy

bombing, strafing and shelling. Precision night shelling of Juno by a 200mm

railway gun at Le Havre continued for some time.

LST’s (Landing Ship Tank)

beached, unloaded in a hurry and withdrew with the tides, if they hadn’t been

hit with shell-fire or bombs. If they had to wait for the next tide, they were

loaded with casualties on stretchers, including those of the enemy. The safest

time for this was in the dark of night with no lights but the risk of accidents,

with so much activity in the darkness, was high. I spent much of my time guiding

in tank and assault landing craft, unloading Sherman and Churchill tanks,

retrieving bodies floating in on high tides and generally doing what had to be

done to help keep the operation moving.

Mobile casualty stations were

quickly improvised along with emergency airfields, which soon became assembly

lines, with DC3 and C147 aircraft landing, being loaded with twelve occupied

stretchers and taking off for England. Having the opportunity to see the entire

operation of the five invasion beaches from my stretcher in one of these

evacuation aircraft was not of my choosing but the sight was truly breath

taking.

On approaching the airfield in

the Midlands of England, one could see hundreds of ambulances with red crosses

on their roofs on the roads leading to the airfield. On being offloaded, each

casualty was examined as to the need for emergency surgery, nationality and

hospital assignment. A large hanger, its floor literally covered with

stretchers, was being used for washing and feeding the patients by young nursing

aids.

The next morning, I awoke in a

large ward at No11 Commando Military Hospital and spent the next few days focusing on

an unspeakable element of the true cost of this war. Medical teams were

constantly working during the days and nights. The sounds in the ward were

pathetic, with many of patients still in shock. The two patients in the beds

next to mine were only eighteen,

with one having his leg off above the knee and the other with both hands

missing.

After being transferred to a

convalescent hospital for a few days, I was posted back to my operational base

on the Isle of Wight and from there to Portsmouth and back across the channel

on an MTB to Normandy. During the two days it took me to find my unit, I

operated tanks for an armoured unit behind Gold Beach. Things were now much less

hectic in the beach areas and it was time for further changes. Sixty years is a

long time but still not long enough to diminish my memories of the greatest

invasion in history.

The British 3rd Division on Sword beach met intense opposition. They

fell behind schedule due to offshore reefs and tricky tidal currents giving the

German defenders valuable time to recover from the earlier bombardment. Despite

this,

the British broke

through the crust of the German defences in an hour but, by then, the resultant

build up of landing craft waiting to unload their cargoes caused congestion and

further delays on the beaches behind them. By early afternoon,

they had expanded their beachhead and linked up with the 6th Airborne Division holding their left flank. In late afternoon,

they repulsed the only serious German counterattack against the beachheads,

destroying 76 of the 21st Panzer Division's 145 tanks. However, they were stopped short of their vital D-Day objective of taking the port city of Caen.

By the end of the day,

the Allied commanders assessed the landings were successful in achieving most of

what had been planned. While the beachheads were not continuous, or as deep as planned, they had successfully broken through Rommel's 'Atlantic Wall.' They had expected 10,000 dead but in the event about 2,500

lost their lives. Total casualties, including killed, wounded, missing and prisoners

amounted to around 12,000, comprising 6,500 Americans, 3,500 British, and 1,000 Canadian.

Omaha

Beach - Supplying the Troops

Considering that the invasion of Normandy involved

the greatest amphibious invasion force in history, it's not surprising that most

accounts of D Day concern Naval Ships and the ubiquitous landing craft.

US Army Lt. Carroll Turner was with the Third Platoon, Company A, 348 Engineers

and his perspective on the invading force was seaward from Omaha Beach. His job was to

offload supplies from Landing Craft Tank (LCTs), across the sand and into trucks for distribution to the troops. Considering that the invasion of Normandy involved

the greatest amphibious invasion force in history, it's not surprising that most

accounts of D Day concern Naval Ships and the ubiquitous landing craft.

US Army Lt. Carroll Turner was with the Third Platoon, Company A, 348 Engineers

and his perspective on the invading force was seaward from Omaha Beach. His job was to

offload supplies from Landing Craft Tank (LCTs), across the sand and into trucks for distribution to the troops.

[Photo; Lt C Turner].

In November of 1943, his

Company moved to Swansea, England. Of this time, he had many happy memories and

friendships, including a British family who appreciated the special significance

of Thanksgiving to a soldier from the United States. He was invited to dinner in

the course of which he produced some corn kernels his mother had sent from home.

Despite severe shortages, frying fat was found and heated up and the kernels

thrown in. The family were amazed when popcorn filled the pan as if from

nowhere... something they'd never seen before!

In the spring of 1944, the Company moved from Swansea to the New Forest on the

south coast of England. The trees provided cover from the

unwelcome

attentions of enemy aircraft but it was very damp and cold.

Out of 201 troops and 7 Officers only 32 reported for duty one day, the remainder

being confined to barracks with colds and pneumonia.

By the end of May, Lt Turner's Company were

briefed on their role in the

forthcoming invasion, although not the timing or location. Their job was to take

supplies from beached landing craft and to transport them across the beach to

waiting trucks. The

impression was given that German resistance would be softened up by bombing and

shelling and that it would be an easy walk ashore.

The men were issued with special invasion currency for France

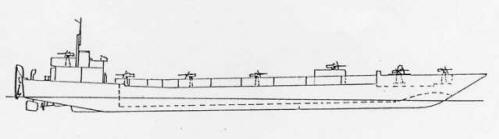

and Belgium before they went ashore. They boarded LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks), which were

"loaded to the gunnels" with trucks and heavy equipment. The LSTs were

capable of 10 mph

but with 'Rhino Ferries' in tow, this was reduced to 3 mph. The Rhino

Ferries were constructed of 4' x 4' x 6' welded steel plates with a diesel engine

to the rear.

Each had an operator and carried around 28 vehicles. The men were issued with special invasion currency for France

and Belgium before they went ashore. They boarded LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks), which were

"loaded to the gunnels" with trucks and heavy equipment. The LSTs were

capable of 10 mph

but with 'Rhino Ferries' in tow, this was reduced to 3 mph. The Rhino

Ferries were constructed of 4' x 4' x 6' welded steel plates with a diesel engine

to the rear.

Each had an operator and carried around 28 vehicles.

[Photo; Loaded Rhino ferry going ashore.© IWM (A 24186)].

In the early morning of June 6th, the Battleship

USS Texas fired

on the German positions with her 14-inch guns. Each shell

cost $10,000, a huge sum of money in 1944, which brought home to Lt. Turner the

great significance of the events that were about to unfold.

As dawn broke, the troops descended rope ladders down the side of their LSTs into LCVPs

(Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel), which would take them on to the landing beaches. The rough

sea and swell made the transfer difficult with 40 lb packs on their backs. Lt Turner's platoon was to land at Omaha Easy Red

beach. Their LCVPs and DUKWS (an amphibian wheeled vehicle)

patrolled up and down the landing beach but could not find

a suitable place to land. The water was full of bodies and debris and despite

early reassurance to the contrary, enemy machine gun fire was heavy. Before the

beach was declared safe for off loading, dead bodies

were removed up the hill to where the

cemetery is now located. 620 bodies were moved that day, which had a profound and

lasting effect on the men concerned.

The Infantry and regular troops landed on D-Day + 1.

An interesting insight into the enemy's use of conscripted men from Eastern

Europe and Russia was provided when the frightened

faces of men and boys confronted them when a bunker door was opened. They had no

desire to fight and just wanted to be

taken prisoner, have a

meal and a place to sleep. They had little allegiance to the German Army.

With

2 bulldozers, 2 cranes and dump trucks at the ready, the platoon was set up and ready for action.

The LSTs unloaded

their supplies into cargo nets which were picked up by the cranes and lifted into dump

trucks. Early loads included barbed wire, TNT and mines. That night, German 88

mm shells landed close by but failed to hit their target. Another early load

comprised 4 tons of beef, which warranted an extra guard on duty.

Since Lt. Turner was a Junior Officer, he was on night duty from 6 pm to

6 am. Difficult though it was, with noisy activity all around, he slept as best

he could during the day. Since Lt. Turner was a Junior Officer, he was on night duty from 6 pm to

6 am. Difficult though it was, with noisy activity all around, he slept as best

he could during the day.

[Photo; Omaha Beach in June 1944].

The work of unloading between 650 to 800 tons

of materials for each of the 6 Battalions was hard, requiring the cranes and dump

trucks to operate 24/7.

Between June 7th and August 31st, 300 LSTs, some LCTs and ‘dumb barges"

were unloaded. In mid June, stormy weather, lasting several days, interrupted the

supply chain, when LSTs were unable to cross the Channel. By the time the

storm broke, ammunition and food was in short supply.

The objective was to unload and, where appropriate, load the landing craft on

the same tide but this was not always possible causing some vessels to be

beached high and dry until the next tide. Usually 3 to 6 LSTs would be unloaded at a time.

Several weeks after D-Day, enough dunnage (rough

lumber used to stabilize shipments) to build a mess hall had been gathered. The Troops appreciated

eating at a table instead of individual K-Rations. Lt. Turner, himself, acquired enough

wood from containers to build an 'office' with space for his

paperwork and a couple of beds. Some of his troops used stone walls around field

boundaries as the sides of makeshift shelters by

throwing a tarpaulin over them. The area at the base of the walls provided

enough space and cover for the men to rest and sleep

regardless of the weather.

Over the succeeding weeks and months the beach was well established and

supplies flowed more smoothly through them and the

Mulberry Harbours. As the

Allies advanced, useable harbours also became available, so for Lt Turner and his men on the beaches,

their important work was largely done. He and his platoon were then assigned to march toward Germany...

but that's another story well outside the remit of this website

LST 427 - Normandy Photographs

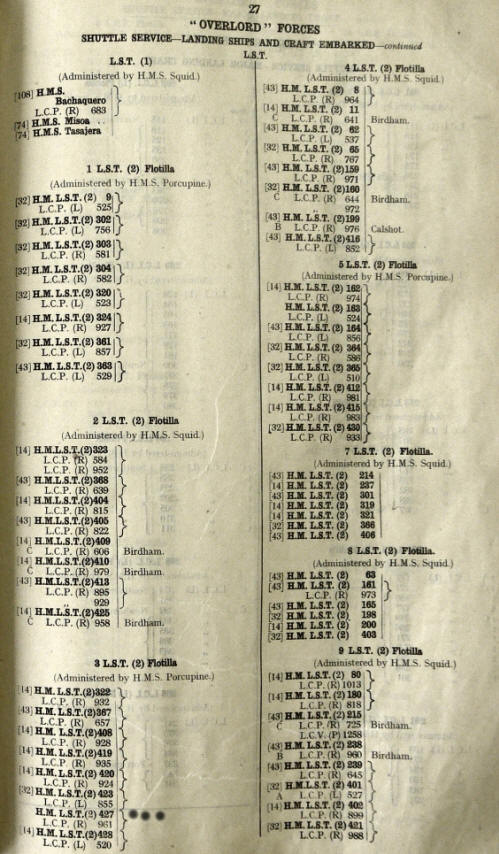

HM

LST 427

served in the Mediterranean from June 1943 to early 1944 as part of the 3rd

LST(2) Flotilla under the command of Flotilla Officer Acting Commander D S Hore-Lacey

RN. She participated in the landings on Sicily, Salerno and Anzio.

On her return to England to begin

'working-up' for the D-Day landings in Normandy, 427 remained part

of the 3rd LST Flotilla, still commanded by Acting Commander Hore-Lacey

who once more took passage aboard the LST 322.

On

D-Day 427 was accompanied by sister ships 322, 367, 408, 419, 420, 423

and 428 forming part of Assault Group S1. Also part of Group S1 was

the

'Reserve' 9th Infantry Brigade of the

3rd British Infantry Division. They would assault Sword beach between La Breche and Lion sur Mer, which was the extreme eastern flank of the

D-Day assault. The landing beaches were given the code names Queen Red

and Queen White. Prior to the arrival of

the 9th Brigade, the 8th Brigade led the way as 'First Assault' but

suffering grievously in the process. They were followed up by the men of

the 185th Brigade.

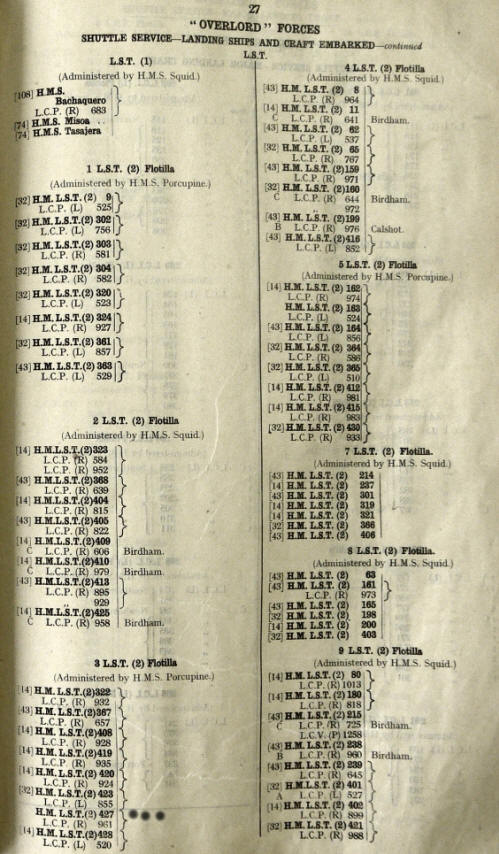

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List'

showing the disposition of 3 LST(2) Flotilla just prior to D-Day].

Ron Hite

who served on LST 427 recalls;

It

was the same hum drum stuff while at sea... on watch, off watch, bit

of dhobing (washing), playing cribbage, chess, perhaps starting a

letter home or something to pass the time. If just finished an evening

watch I'd usually shower and go straight into the flea bag, hoping

action stations wouldn't sound, so I'd get a few hours kip.

When

close to a landing it was a hive of activity in the engine room,

especially the auxiliary engine room. It was essential to know what

engines would be required after the 427 beached. The cooling systems

for those engines were transferred from direct sea intake to on board

tank cooling system as 427 would soon be high and dry. All generators

were started and on line to provide enough power to open the bow

doors, lower the ramp ready for discharge, and

operate the elevator to

transfer vehicles from the top tank deck to the lower deck for

discharging. operate the elevator to

transfer vehicles from the top tank deck to the lower deck for

discharging.

[Photo; Reunion of ship's crew. Date unknown but

possibly late 40s.

The CO is 4th from

the right in the second row from the front,

and Ron Hite is in the front row first from right].

There was

of course a risk of enemy action against the craft while she was

beached so we made sure that fire hydrants on the upper deck were

clear of obstructions. When all was done it was a case of keeping our

heads down hoping the enemy were otherwise preoccupied. We were

vulnerable to attack while 427 waited for the next tide to take her

off the beach.

Further

Reading

Elsewhere on

this website there are 40 remarkable D Day

stories - an historical legacy left behind by veterans who were there.

There are around 300 books listed

on our 'Combined Operations Books' page. They, or any

other books you know about, can be purchased on-line from the Advanced Book

Exchange (ABE). Their search banner link, on our 'Books' page, checks the

shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Just type in, or copy and paste

the title of your choice, or use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's

no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Website pages on this site.

Visit

D Day Landing Craft

for a nautical view of the landings from the personal reminiscences of those manning the craft. Also

Coastal

Command

for an account of their anti-submarine patrols on D-Day.

A Dutch website

about Normandy with English

version.

" D-Day Commando" From Normandy to the river Maas by Ken Ford. It also

describes the part of 48 RMC in the liberation of Walcheren. Published in the UK

in 2003 by Sutton P.Ltd ISBN 0-7509-3023-3.

Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II by Stephen E. Ambrose - 1994. ISBN

0-671-67334-3

Six Armies in Normandy by John Keegan. 1982. ISBN 0 7126 5579 4.

The Second Front - World War II by Douglas Botting and the Editors of World Time Books. 1978.

ISBN 0 8094 2498 3.

Short Sea Long War by John des S Winser. Published by World Ship Society, Gravesend, Kent. ISBN 0

9056 1786 ? - the story of 119 Cross Channel ships commandeered by the R.N. to fly the White Ensign.

Le Jour J au Commando N° 4 by René Goujon (French Kieffer Commando), published by Editions Nel 1, rue Palatine, 75006 Paris

tel 00 33 1 43 54 77 42. Enquiries in English to the author's daughter at

armoria.d.ylfan@hotmail.fr

Correspondence

SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL 6th AIRBORNE VETERANS

06-06-06

Dear Sirs and Families,

Our family, the BROOKE Family, wish to extend our sincere gratitude and

remembrance for those of you, your friends and to the extended families for

your magnificent and brave actions of 62 years ago today, June 6th 1944, which

cleared the way for the end of Nazi tyranny in Europe and the world.

Both my father and his twin brother were serving with the Royal Navy Fleet

Air Arm on the the English Coast on June 5th and 6th 1944 awaiting transfer to

Canada for flight training to become pilots. My father, John Brooke, (FX605708)

died in January 21st 2004 at the age of 77.5 years, of melanoma. He was enlisted

at the age of 16 in the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. Although by May 1945 his

training ended as the war was coming to a close he never saw active service.

During our visit to Normandy, a trip he wanted to do for nearly 25 years, he

expressed to me his life long sincere respect and thanks to all those of his age

who did see active service at the age of 17. I know that he felt some guilt as

his training to become a pilot was all that possibly stood between him and the

active duty. To this end he actively remembered and honoured you his peers and

their families for their great commitment to world future. Before his health

deteriorated in 2003 I was able to take him with my mother to Pegasus Bridge on

the summer of 2003. Upon visiting Pegasus Bridge and the 6th Airborne Museum he

noted to me his strong admiration for the skills of Glider Pilots of the 6th

Airborne. He had started glider flying in the ATC in 1941 in Birmingham area.

His emotions, along with ours were very touched.... it is a very moving place...

as it should be!

Additionally, it was with great pride that I was able to take my children to

Pegasus Bridge to let them experience the importance of the events of this day.

They remember and are respectful.

To you all on this most important day. Thanks, and we remember.

Kind Regards

Richard S. Brooke, N.A., P.Eng., Mannerheimintie, Helsinki, Finland.

Pegusas

Bridge Veterans.

The photo was taken in London early June 1999. These gentlemen

were returning from a tour of Greenwich on the same boat as my

sister and I (and they were having a grand time!) As we were

waiting to leave the boat, we noticed their lapel pins of

Pegasus and we talked with them for several minutes, thanking

them for their service, etc. They were in London to take part

in the Trooping of the Colour (I believe the next day). I

recall some of their relatives were with them, and they might remember this

encounter. I am still awed at the bravery of those who took part in D-Day. Thank you. Dot Weathersby,

Terry, MS. USA (6/09) Pegusas

Bridge Veterans.

The photo was taken in London early June 1999. These gentlemen

were returning from a tour of Greenwich on the same boat as my

sister and I (and they were having a grand time!) As we were

waiting to leave the boat, we noticed their lapel pins of

Pegasus and we talked with them for several minutes, thanking

them for their service, etc. They were in London to take part

in the Trooping of the Colour (I believe the next day). I

recall some of their relatives were with them, and they might remember this

encounter. I am still awed at the bravery of those who took part in D-Day. Thank you. Dot Weathersby,

Terry, MS. USA (6/09)

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks to

George H Pitt, Alberta, Canada for the main Operation Overlord article and to

Bill Newall, Stan Grayland and Judy, widow of Bill

Spencer of LST 325 Blue Crew, for additional information. Further

additions and redrafting for website presentation by Geoff Slee.

HMLST 427 comments & Photos; The foreword and

historical notes on

the craft are by Tony Chapman, official

Archivist/Historian of the LST and Landing Craft Association.

Photographs provided by 427 veteran, Ron Hite. the craft are by Tony Chapman, official

Archivist/Historian of the LST and Landing Craft Association.

Photographs provided by 427 veteran, Ron Hite.

|

"It is my unshakeable decision to make this front impregnable against every enemy"

declared Hitler in a speech he delivered in December 1941 when he

boasted, to the world, that Germany controlled the entire west coast

of Europe from the Arctic Ocean to the Bay of Biscay. His impregnable

defences included some 15,000 strong-points which were to be manned by

300,000 troops.

"It is my unshakeable decision to make this front impregnable against every enemy"

declared Hitler in a speech he delivered in December 1941 when he

boasted, to the world, that Germany controlled the entire west coast

of Europe from the Arctic Ocean to the Bay of Biscay. His impregnable

defences included some 15,000 strong-points which were to be manned by

300,000 troops.